By Robert F. McEniry

On May 13, 1943, nearly 300,000 Axis soldiers surrendered to the Allies in northern Tunisia. This successful conclusion to the North African campaign led to speculation at the time as to where the Allies would strike next.

The Axis had to consider all possibilities for future invasions, including assaults on Sicily, Sardinia, Corsica, and even Greece. Unknown to the Germans and Italians, the Allies had decided during the January 1943 Casablanca conference that Sicily would be the next target following the successful conclusion of the North Africa campaign, under the code name of Operation Husky.

While conducting the operational planning for Husky in February 1943, General George C. Marshall, the U.S. Army chief of staff, informed Allied Forces commander Lt. Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower that the U.S. Navy could not provide auxiliary aircraft carriers for air cover for an assault on Sicily.

Marshall then suggested the Allies seize the Italian island of Pantelleria for its airfield, which could be used by Allied fighters to support the Sicilian invasion. Since the island was located between Tunisia and Sicily, its location was ideal. In addition to providing an unsinkable aircraft carrier for the Allies to project air cover over Sicily and wide areas of the Mediterranean, Pantelleria had to be reduced to prevent it from being used as an effective warning post of an Allied invasion of Sicily. With its radar station, observation and listening posts, and its ability to host reconnaissance aircraft, the island could easily monitor Allied air and sea activities and eliminate any chance of achieving surprise in an assault on Sicily.

General Eisenhower was not thrilled at the prospect of seizing Pantelleria and other nearby islands, and although planning continued he looked for reasons not to have to invade and occupy the island. In May 1943, the matter came to a head when it was decided that the invasion of Sicily required landings on the southeast corner of that island. Given the planned invasion of Sicily and its location, the matter was settled. Pantelleria had to be taken. The military issue was how best to take or reduce Pantelleria Island.

The Defenses on Pantelleria Island

Pantelleria is located 53 miles from Tunisia, 63 miles from Sicily and 120 miles west of Malta. It is a volcanic island roughly 16 miles long, by 5.6 miles wide with a total area of about 45 square miles. The island is elliptical in shape with sheer rugged cliffs, a rocky coastline, and a countryside with rocky barren hills. The highest point on the island is Montagna Grande at 2,742 feet.

Pantelleria was an Italian possession, and its defenses were improved by the Italian government in the 1920s. In 1926, Mussolini declared Pantelleria a prohibited military zone. In 1935, the Italians started to build an airfield and construct coastal fortifications and antiaircraft batteries.

By 1939, the airfield was completed. It was an impressive facility for its day, with a 5,000-foot runway with an underground aircraft hangar hewn out of solid rock. The underground hangar was 1,000 feet long and 85 feet wide with a capacity for 80 aircraft. The hangar also had its own power plant and water storage facility. With a 33-foot covering of earth, the underground hangar was thought to be impervious to air or naval bombardment.

The antiaircraft defenses consisted of two batteries of 10 modern 90mm guns and 13 batteries of 72 dual-purpose 76mm guns, which were useless against aircraft flying at medium or high altitudes. The antiaircraft defenses were fortified with an additional four-barreled 20mm Flak 38 gun located near the airfield and six 20mm guns near the harbor area and next to German Freya surveillance radar and a Wurzburg D tracking radar. These additional guns and radar installations were manned by around 600 German troops.

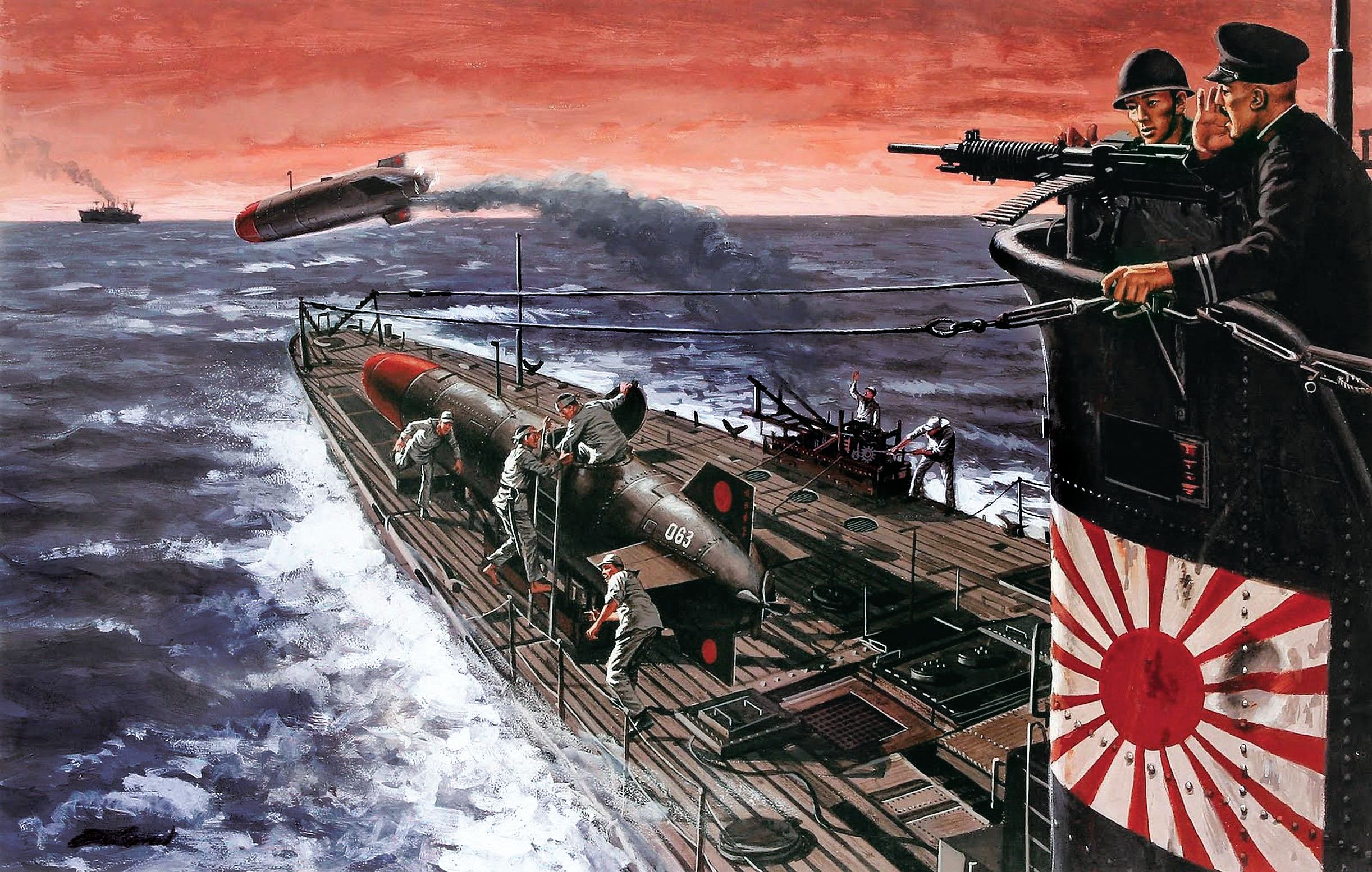

For protection from sea attack, the island boasted three shore batteries with four 152mm guns each. The Italians also had used the island as a refueling and servicing station for Axis submarines and torpedo boats, where they could also rearm with mines or torpedoes.

The primary ground defenses were provided by the Italian garrison commanded by Vice Admiral Gino Pavesi. The Italian forces included the Air Force personnel commanded by Lt. Col. Francesco Raverdino, some militia, and a mixed brigade of 7,400 Italian Army troops commanded by Brig. Gen. Giuseppe Maffei. The total number of Axis troops on the island was about 12,000.

While these defenses looked formidable on paper, the island had a number of significant weaknesses. First, the defenders had little or no combat experience and were not considered high-quality troops. At this point in the war many Italians had grave doubts about the war and their government, and Italian troops had not always fought effectively in North Africa. Over 10,000 Italian civilians lived on the island, and many had relatives among the garrison. During the battle these civilians would add an extra burden on the defenders in terms of water and food supplies and providing adequate protection from air raids for the population.

The failure of the Italians to evacuate the civilians before the battle was a serious mistake. The Axis forces in the Mediterranean Theater were outnumbered at sea and in the air and effectively had lost control of both to the Allies. The question seemed, for both sides, to be less centered around whether Pantelleria would fall than exactly how long the island could hold out against an Allied landing.

A Test For U.S. Heavy Bombing Tactics

On May 9, 1943, Eisenhower began preparations for the assault on Pantelleria. He ordered a concerted effort by Allied airpower, including units of the Royal Air Force and the U.S. Northern African Air Forces (NAAF) against Pantelleria. He further directed a naval force under the command of Rear Admiral R.R. McGrigor of the Royal Navy to blockade the island and provide gunfire support.

The landing force would consist of the British 1st Division under Maj. Gen. Walter E. Clutterbuck.

On May 13, Eisenhower told Army chief of staff, General George C. Marshall, “I want to make the capture of Pantelleria a sort of laboratory to determine the effect of concentrated heavy bombing on a defended coastline. When the time comes we are going to concentrate everything we have to see whether damage to material, personnel and morale cannot be made so serious as to make a landing a rather simple affair.”

The Allies were initially planning to bomb the island into submission. U.S. Army Air Forces Lt. Gen. Carl A. Spaatz would be in charge of the operation. Spaatz had a potent air force at his disposal for what came to be known as Operation Corkscrew. He had four Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress heavy bomber groups with 192 aircraft (2nd, 97th, 99th, 301st), four North American B-25 Mitchell groups (310th, 321st, 340th, 12th), three Martin B-26 Marauder groups (17th, 319th, 320th) with a combined 285 aircraft, one Douglas A-20 Havoc group with 57 aircraft (47th), three wings of Lockheed P-38 Lightning fighters (1st, 14th, 82nd), and three wings of Curtiss P-40 Tomahawk fighters (325th, 33rd, 324th), to total 300 aircraft.

It is worth noting that the participating U.S. 33rd Fighter Group also included the 99th Fighter Squadron. This squadron was the first of the Tuskegee Airmen squadrons. These squadrons were manned and piloted solely by African American airmen. During the Pantelleria campaign the men of the 99th flew their first combat missions. Flying P-40s were Lieutenants William Campbell, Charles Hall, Clarence Jamison, and James Wiley, and in June, six of the 99th’s pilots became the first black airmen in the Army Air Forces to take part in aerial combat when they traded shots with German fighter planes.

Meanwhile, the British Commonwealth contribution to the campaign consisted of three wings of Royal Air Force Wellington bombers plus one South African Air Force Wellington wing in No. 205 Group, four RAF and SAAF A-20 Boston Mk III bomber squadrons (12th and 24th), RAF 326 Wing with Bostons, two squadrons of Baltimore bombers with Hurricane fighters, and RAF 242 Group.

Concerns About the Operation

The main air assault was to begin on May 18, 1943, and would consist of 50 mediumbomber sorties and 50 fighter-bomber sorties daily against the island through June 5. On June 6, the plan would shift to around-the-clock aerial bombing that would increase in intensity up to the scheduled invasion day, June 11. The smaller islands of Lampedusa, Linosa, and Lampione would be reduced after Pantelleria’s fall.

Opposing this air armada were approximately 900 Axis aircraft. These included 90 Italian fighters stationed on Sicily, consisting of 52 Macchi 202 aircraft, 23 Macchi 205, and 15 Macchi 200 aircraft plus seven Me-109 fighters operating within the 1 and 53 Stormo (Wings). The Germans possessed Luftflotte 2 under the command of Field Marshal Albert Kesselring, which included 130 Me-109s in JG27 and JG53, 80 FW-190 fighters in Sturmgeshwader 10 and Schachtgeschwader 26, plus 30 Me-110 long-range fighters, and 20 Ju-88 night fighters for about 357 total Axis aircraft. The remaining planes were scattered from Sardinia to Corsica and the Italian mainland but were within striking range of Pantelleria.

Not all Allied commanders were comfortable with the invasion plans. Clutterbuck, a more traditional ground commander, expressed grave doubts as to the ability of airpower to reduce the defenses of the island and prevent his troops from enduring heavy casualties. His protests so exasperated Spaatz that in private he began to refer to the general as “Clusterbottom.” McGrigor had no such misgivings and gave the plan his full support.

Consultation With Professor Solly Zucherman

In planning the operation, Spaatz sought the help of his scientific adviser, Professor Solly Zuckerman. Zuckerman was an expert in what was then the new field of operations research, which attempts to apply mathematical concepts to determine optimal plans of action. Zuckerman analyzed the problem with his Operations Analysis Unit and produced a detailed bombing plan that provided precise aiming points, called for detailed reports and analysis of each sortie, required extensive photo reconnaissance, and demanded plotting of every bomb burst on a grid noting any damage caused.

Due to the accuracy of bombing in 1943, Zuckerman recommended that the bombs be concentrated on those gun batteries that threatened the proposed landing beaches. All bombing sorties were registered by target, and daily photo reconnaissance was conducted by the 248th PR Wing. If it was determined that a target was eliminated, the bombing missions were adjusted. If not, strikes continued until the target was assessed as destroyed.

The effort also included psychological operations with several leaflet drops. The first was on May 13, 1943, warning the civilian population of the upcoming raids and giving them a five-day grace period to evacuate. Additional leaflet drops encouraged the surrender of the garrison.

1,500 Sorties Over Pantelleria

The air offensive began on May 18 with the first daylight sorties. At night, RAF bombers dropped 4,000-pound blockbuster bombs, and RAF Hurricane fighters dropped additional bombs to cause the inhabitants to lose sleep. On May 21, P-40 and P-38 fighters destroyed the Wurzburg radar apparatus, and on May 23, the Freya radar was abandoned. This effectively rendered the island blind to incoming Allied air attacks and prevented warnings to Axis air bases in Sicily.

From May 18 to May 29, over 1,500 sorties were flown against the island with 1,300 tons of bombs dropped. These sorties targeted the harbor, airfield, and shore batteries with 900 tons of bombs dropped on the port and airfield and 400 tons devoted to the shore batteries. The heavy B-17s commenced operations on June 1.

The second phase of the bombing campaign began June 6 and lasted six days. The attacks increased in ferocity from 200 sorties on the first day to 1,500 by June 11. During this phase an amazing 5,324 tons of bombs and 3,712 sorties were flown against the island. All this bombing reduced the developed areas of Pantelleria to destruction and chaos. Damage to the port, roads, housing, and phone lines was extreme. The electricity production facilities were knocked out, and several of the shore batteries were destroyed.

The Axis Response

Axis forces tried to respond to the aerial siege as best as they could. Three small cargo ships braved the blockade and managed to land their cargoes but were then sunk. The Regia Aeronautica (Italian Air Force) flew 324 sorties during the first 10 days of June, losing 16 aircraft and made unsubstantiated claims of 24 Allied aircraft shot down. The Italian losses also included seven Macchi MC-202 fighters in one day of air combat.

The Regia Aeronautica flew nightly resupply missions to the island, bringing in small amounts of critical supplies and evacuating wounded personnel. The Italian government maintained radio communication with the island throughout the siege and implored the defenders to resist to the end.

The Luftwaffe flew several hundred sorties, but its support was halfhearted at best. Most of the Luftwaffe sorties were against Allied airfields or fighter sweeps in the vicinity of the island. The Luftwaffe lost 10 aircraft and claimed more than 20 Allied planes.

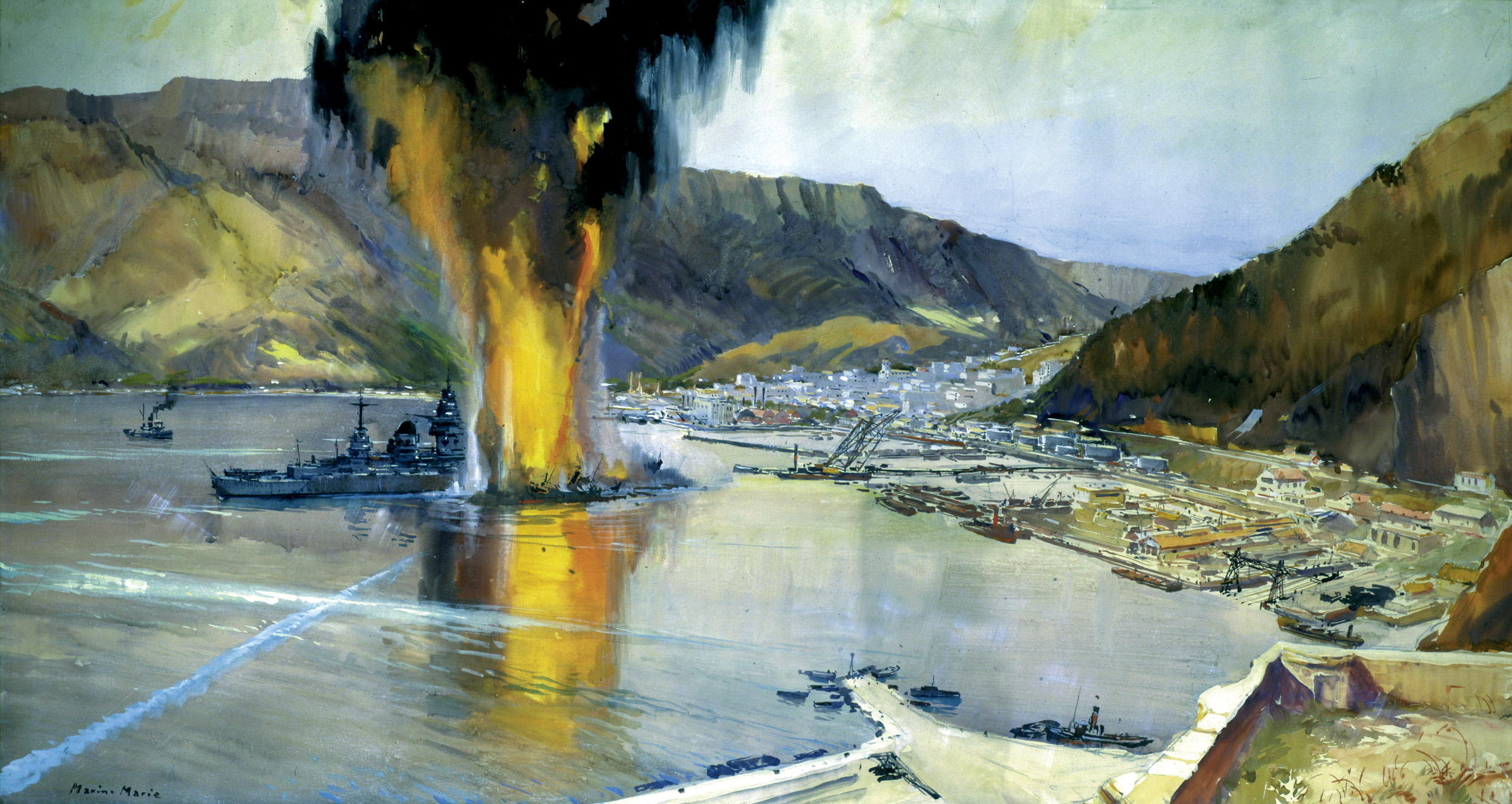

The Allies conducted a naval demonstration off Pantelleria to test the island’s defenses. The Royal Navy dispatched the cruisers HMS Aurora, Newfoundland, Penelope, and Orion, the antiaircraft cruiser Euryalus, the destroyers Whaddon, Troubridge, Tarter, Jervis, Nubian, Laforey, Lookout, and Royal, and the gunboat Aphis.

With McGrigor aboard his flagship, HMS Whaddon, were Spaatz, Clutterbuck, and Zuckerman. Eisenhower and Admiral Andrew Cunningham, commander in chief of the Royal Navy in the Mediterranean, were aboard Aurora. During the course of the naval bombardment, which began about 10 am, the Italian shore batteries responded weakly. An hour later, medium and heavy bombers attacked two shore batteries.

The naval task force was attacked by German and Italian planes, which were quickly driven off. Both Eisenhower and Cunningham were pleased with the results of the combined naval and air operations. Eisenhower informed Marshall that they “were highly pleased both with the obvious efficiency of the air and naval bombardments and with the coordination achieved as to timing.”

On June 10, 1943, leaflets calling on the island garrison to surrender were again dropped. The only radio station still working on the island broadcast that “despite everything Pantelleria will continue to resist.” Over 20 additional messages were sent that night reporting the damage done to the island. Allied intelligence had decoded these messages and also knew that the garrison was in a desperate situation.

Storming the Island

That same day, the British 1st Division embarked on the infantry landing ships HMS Queen Emma, Princess Beatrix, and Royal Ulsterman. Tanks, guns, and equipment were carried aboard numerous landing ships. The invasion force set sail on the night of June 10. The following morning found the invasion fleet eight miles off the harbor of the port of Pantelleria. The sea was calm. The troops took to their assault boats, and B-17s timed their last raid just prior to the landing around 11 am.

With the invasion imminent, Pavesi met with his senior staff that morning. They reviewed the situation, and with dwindling supplies of ammunition, the destruction of communication systems, the loss of the main water and electric plants, and no hope of resupply or reinforcement it was determined that the garrison should surrender.

Pavesi had wired his superiors several hours earlier, stating, “The situation is desperate; all possibilities of effective resistance have been exhausted.”

Unknown to the admiral, Mussolini had sent him a message at 10:10 am on June 11, instructing Pavesi to surrender at noon. As it was, Admiral Pavesi took action himself and instructed his air forces commander to place a large white cross on the airfield runway to signal surrender. He sent instructions to all his forces to cease firing as of 11 am local time.

As the garrison was making preparations to surrender, the Allies were making their amphibious assault on the island. The Royal Navy warships started their shore bombardment around 11 am, and the landing craft made their way toward the island at 10:30. The Luftwaffe executed a series of attacks, as several dozen FW-190s attacked the flotilla and five Me-109s attempted to strafe the landing craft. The FW-190s missed the ships, and the Me-109s were driven off by P-40s of the 57th Fighter Group. At 11:45, B-17s added a crescendo of bombing to the island as the landing force approached.

The first wave of the landing consisted of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Division, which included the 1st Duke of Wellington Regiment, 1st Shropshires, and 2nd Sherwood Foresters Regiments reinforced with a squadron of tanks and a field artillery regiment. By noon, the entire first wave was ashore near the harbor. All of the Italian batteries had ceased firing at 11:30, and white flags began to appear all over the island. Allied naval shelling ceased, and all air and naval bombardments were canceled as of 12:45.

The only casualty suffered by the Allies during the landing and occupation occurred when an unlucky corporal of the 2nd Sherwood Foresters was kicked in the head by a mule and perished. Clutterbuck came ashore at 1:30 after most of the island’s garrison had already surrendered. The formal surrender documents were signed in the underground hangar by Clutterbuck and Pavesi at 5:30.

The Strengths and Limitations of a Bombing Campaign

After the fall of Pantelleria, Lampedusa was subject to two days of violent bombing. The Luftwaffe responded only with long-range fighter sweeps that resulted in 14 Axis fighters shot down. The island was then bombarded by four light cruisers and six destroyers on the morning of June 12. The island garrison tried to surrender to an RAF pilot who landed on the island’s airfield due to engine failure. When bad weather cleared, the 4,600-man garrison surrendered, and Lampedusa was occupied on June 13.

Operation Corkscrew was a splendid victory for the Allies. The island was taken on schedule, and 11,621 Italians and 78 Germans were taken prisoner. When prisoners from Lampedusa are included, over 16,000 Axis soldiers were captured.

As for airpower’s overall effectiveness during Operation Corkscrew, post-campaign analysis showed varying results. While all the mission objectives for airpower were achieved, only 108 Axis soldiers were killed and 200 wounded by Allied air attacks. Considering the size of the garrison and the weight of the bombing, these were meager casualties indeed.

Zuckerman’s analysis of the bombings showed very little damage to the underground facilities. As a matter of fact, the underground hangar and related facilities proved impervious to the Allied bombing. Most above-ground installations were devastated. The data showed surprising results as to which type of bombing platform was the most effective. While bombing had been predicted to place 10 percent of the ordnance within a 100-yard radius of the enemy gun batteries, this was rarely achieved.

Medium bombers did the best with 6.4 percent of their bombs within 100 yards. The B-17s were second at 3.3 percent, while fighter-bombers were last at 1.6 percent. For the entire campaign, a total of 5,285 sorties were flown against the island with a total of 6,200 tons of bombs dropped. U.S. bombers flew 83 percent of the sorties and dropped 80 percent of the bombs.

It was agreed during the post-operation analysis that the most important factor enabling the Allies to conquer Pantelleria from the air was the low morale of the garrison. It would have been nearly impossible to compel the surrender of a fanatical enemy, entrenched behind hardened and deeply buried works, by airpower alone.

Airpower had won a decisive tactical and operational victory on Pantelleria Island. It was also a victory of strategic significance for the Allies in that it opened the door to Sicily. Some airpower proponents could also claim a historic, albeit disputed, achievement that the victory was obtained almost exclusively by airpower.

The valuable lessons learned during Operation Corkscrew would be applied to all future Allied invasions in Europe. While the controversies about airpower effectiveness continued, the Allies had earned the right to pop a few corks in celebration of Operation Corkscrew.

I have a photograph of the bombing of Panteleria from my late father’s personal collection, taken by his undergunner of the aircraft following his – and therefore of his bombs striking ‘Signal Hill’. I believe that it is the same photograph that you have on this page.

The photograph has tech details on it including height, time/date and direction.

I would be happy to supply further details and a copy.

You should definitely share all material you have, if not here somewhere else on the net.