By Mark Carlson

For nearly three years World War II in the Pacific surged, raging in a hundred places from the Coral Sea to Guam, from Guadalcanal to Tarawa, and from Wake Island to the Philippines. No longer on the offensive, Japan was running out of resources as U.S. submarines sank its merchant fleet. But the Imperial Navy Combined Fleet refused to see the obvious: that Japan would lose the war.

Japan’s military leaders were focused on a new—and desperate–secret weapon being built by the hundreds that would soon be ready to turn the tide of war against the U.S. There was no doubt that the weapon and the brave Samurai warriors being trained to employ it would bring a smashing victory.

On the night of November 20, 1944, two Japanese submarines, running silently on batteries, crept eastward to the largest opening in the reef that surrounded the 230-square mile lagoon of Ulithi in the Caroline Islands. Ulithi was the U.S. Navy’s largest forward base, with everything from destroyer escorts to aircraft carriers. Numerous anchorages, pontoon piers, and depots supplied and repaired the fleets between invasions and campaigns. A mandated possession of Japan, it was captured in September 1944. More than 24 miles long and 22 wide, the deep lagoon and its 40-odd islands had been converted in less than three months into a massive supply, replenishment and repair base.

U.S. destroyers with sensitive sonar hydrophones patrolled the entrances. Radar swept the sky and the sea, but luck often favors the brave. The water was deep enough for the subs to approach. Through their periscopes, the captains had seen several tankers and transports, at least one large cruiser, and beyond them on the horizon, several more big ships, including aircraft carriers. Ulithi was open to Japan’s new secret weapon.

When I-47 was as close as Lieutenant Commander Genji Orita dared, he signaled the engines to stop. Onboard the sub, besides its 100-man crew, were four young volunteers for the historic launch of the new weapon—including Lt. Sekio Nishina, one of the original designers and test pilots. He held a small white wooden box of the ashes of Lt. Hiroshi Kuroki, his co-designer, killed in an accidental explosion. Nishina, with the ashes of his dead comrade, would be the first to enter the lagoon and sink an American warship.

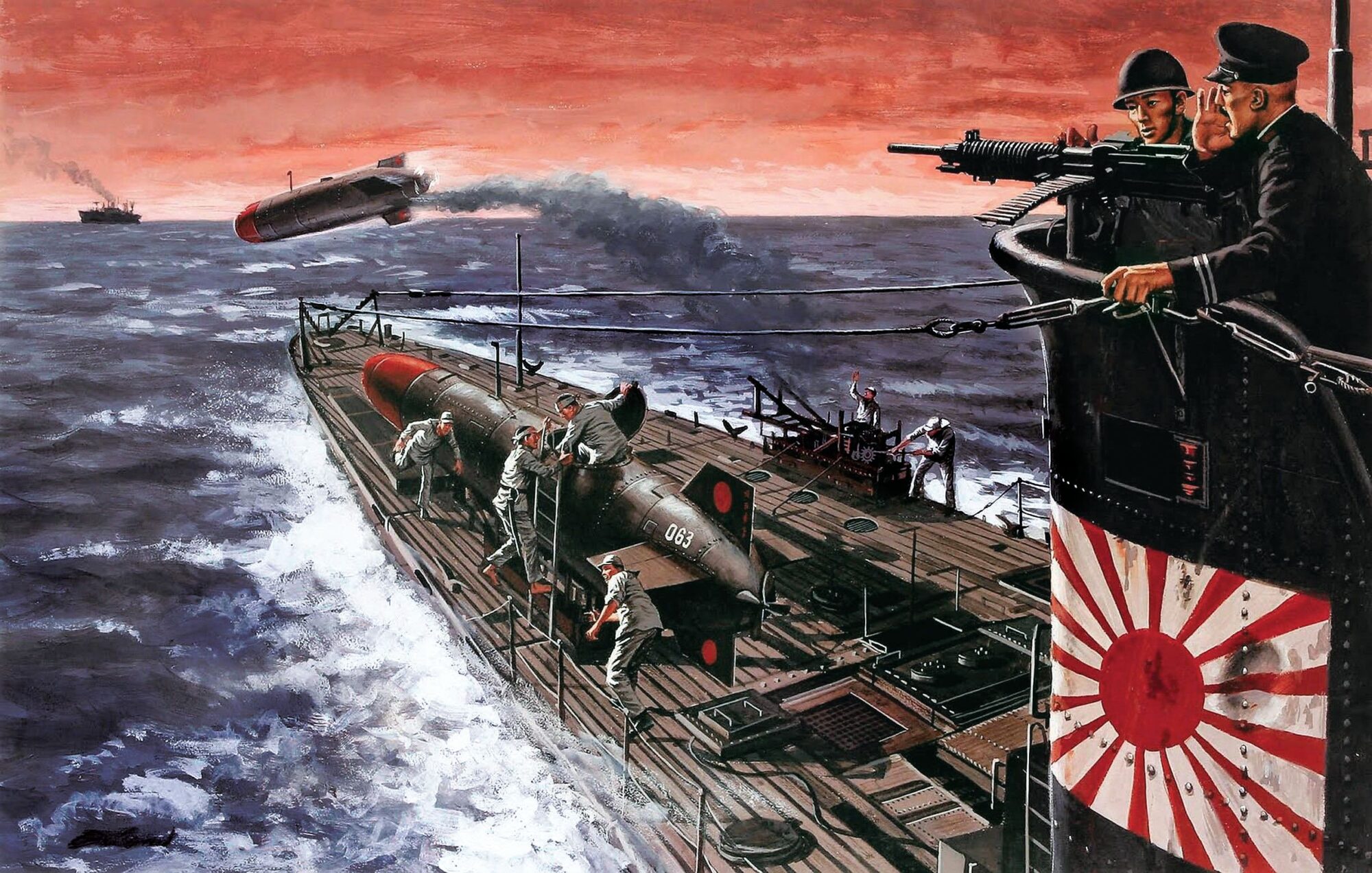

The four pilots stopped to pray at the sub’s small Shinto shrine. Then they paid their respects to Orita and left letters, poems, and keepsakes to be sent to their families. They wore dark jumpsuits, a short ceremonial sword and a white silk hachimaki emblazoned with the Imperial Rising Sun. Shackled on the sub’s deck on wooden cradles were four modified Type 93 Long Lance Torpedoes, 48 feet long and three feet in diameter. Each had a small humped protrusion jutting up amidships, fitted with a periscope. There were diving planes on the bow, just behind the 1,500-pound warhead.

They were Kaitens (“Turn the Heavens”)—the newest version of the kamikaze (“Divine Wind”) that had damaged many U.S. ships in the past year. Like the kamikazes, the Kaiten pilots were to drive directly into the hulls of ships, going out in a blaze of victory for the emperor.

Lieutenant Nishina and his fellow Kaiten pilots would be the first to strike the blow that would assure the future of Japan. Still carrying his box, Nishina watched as a crewman undogged and opened a hatch set into the sub’s overhead hull. Having as many as six holes cut through the pressure hull was not something a sub crew took lightly, but it eliminated the need to surface in enemy waters to launch the Kaitens. Nishina slid up into the narrow access shaft and into the cramped compartment, settling into the canvas seat behind the simple control panel. Once he was inside the big torpedo, ahead of the hydrogen peroxide motor and behind the air flask that activated the rudder and diving planes, he closed the hatch below him.

The hatch locked when closed, assuring the pilot could not escape. There was a self-destruct lever if capture was imminent. A battery would provide light to see the instrument panel. Stifling and damp, the interior smelled of oil, peroxide, seawater, and recent welding. The cockpit held enough oxygen for at least half an hour. Air was then filtered through sodium peroxide filters, a primitive precursor to what would be used in manned spacecraft a generation later.

After checking his trim, he gripped a yoke control for the diving planes and his feet rested on a rudder bar. The torpedo left its wooden cradles with a few clanks and bumps, then rocked slowly.

Nishina checked the periscope to be sure he was clear, then activated the motor. With a deep thrumming, the 550-horsepower motor came to life, spinning its contra-rotating bronze propellers. In moments Nishina was moving at about 15 knots. He took his bearing from the gyroscope and headed away. From that point on nothing is known for certain. With a maximum range of nearly 40 miles, he could reach anywhere in the vast lagoon. His only thought would have been on his mission. Before him was Ulithi, which only three months before, had belonged to Japan.

Now it was full of enemy ships, and he was determined to sink one, preferably a battleship. He would avenge Japan and his dead comrade, Hiroshi Kuroki.

While the Combined Fleet had faith in the Kaitens, few submarine officers did. They had good, long-range submarines and well-trained crews. Each sub carried at least 19 Type 95 torpedoes, a variant of the successful Type 93 Long Lance that had inflicted such damage on the Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor and Guadalcanal. The Type 93 was the world’s best, surpassing the G7A used by German U-boats.

Unleashed on the long and vulnerable sea routes between the U.S. and the War Zone, the Imperial Navy’s sub fleet could cut off all supplies and ammunition to the front. Germany had near success in World War I and was still doing well in the Atlantic. The hated U.S. Navy’s fleet of submarines were daily sinking Japan’s merchant fleet, causing major shortages across the island nation. Fuel was in short supply, making fleet plans difficult. Iron ore, needed to make the steel for new ships and tanks, was being cut off. Even food was growing scarce, and there were periodic blackouts in the cities. It was obvious to any pragmatic line officer the best way to win was to cut the U.S. Navy off from its supplies.

But a tradition that went back to the days of feudal Japan reared its head even in the mid-20th century. Bushido was the unbreakable code of the samurai, who were trained from childhood to fight and kill any enemies with their deadly katana swords. Samurai lived for the opportunity to face a worthy foe and defeat him in mortal combat. The word “worthy,” in naval warfare of the 20th century meant warships. Only a ship carrying guns and able to fight back was considered a proper adversary for the modern naval samurai.

The Japanese submarine force was forbidden to attack unarmed merchant ships, even to the point of ignoring them when a worthy target presented itself. It was no way to win a war. Imperial Navy subs had sunk some capital ships, the carriers Yorktown, Wasp, and Hornet. They had also damaged battleships and sunk numerous destroyers. But with transports outnumbering the surface fleet’s war vessels nearly 20 to one by 1944, those sinkings little in the quest for victory. U.S. industrial might was launching new carriers so quickly that Ulithi Lagoon was home to a dozen big fleet flattops by November 1944.

The High Command was interested only in the grand gesture of destroying the U.S. battle fleet. Such triumphs would put steel in the hearts of Japan far more than a list of nameless transports. But there could be no doubt, the fossilized admirals at Yokosuka saw something had to be done. The seeds had been sown by Admiral Onishi, the father of the kamikaze. By mid-1944, his Special Attack Force had claimed many U. S. ships and lives. But he had thousands of planes and pilots who had been quickly trained to dive their bomb-laden planes into enemy ships. But they suffered shocking losses. Still, the idea of a suicide craft mated to a submarine was not too great a leap to two young submarine officers, Lieutenants Sekio Nishina and Hiroshi Kuroki.

Desperate to destroy enemy ships, High Command tried suicide boats loaded with explosives, suicide divers carrying magnetic limpet mines, and even human suicide mines. Ultimately, they saw a torpedo with a human pilot as their best hope. Proposed by Nishina and Kuroki in 1943, it was not until February 1944 that Combined Fleet submarine and torpedo officers looked at it.

The first concept was simply a Type 93 torpedo mated to a cylinder housing the pilot. With crude controls and an electric gyroscope, the pilot could steer the hybrid craft reasonably well. Being only a test, no warhead was used. Experiments led to a modified Type 93 with the guidance system removed to make room for the pilot, who would be cramped in a tube along with 1.5 tons of high explosive.

By the summer of 1944, the Type 1 was under construction. Eventually, over 300 would be built in six variants.

Testing and training was done in the Inland Sea at the island of Ōtsushima. The facility was fitted with launching ramps, repair and machining shops, cranes, and classrooms. A shallow bay allowed the tests to be overseen. Most Kaiten volunteers were in their early 20s, but some were as young as 17. They trained in the unarmed craft, learning how to use the controls and navigation equipment. Each candidate learned how to manage the unwieldy craft in daylight, in circles, toward specific points, and getting a feel for the controls. Then they advanced to night attack simulations, using the periscope and illuminated panel. They learned to navigate around rocks and obstacles and how to trim the craft as the hydrogen peroxide fuel was expended. Final training was in the open sea, being launched from a mother sub and moving at the full 40 knots at a target ship. A dozen pilots, including Kuroki, were killed. Even sans warhead, hitting a ship at that speed was dangerous.

No one denied that an attack would be very hazardous, and even more so, in patrolled enemy waters.

The two mother submarines, I-47 and I-36, had reached a favorable launch point without being detected. To the west a waxing crescent moon cast little light on the sea. The subs were only able to launch four Kaitens in all, with one running aground. The other three made it into the lagoon, their pilots determined to die for Japan and their emperor.

Inside the atoll, the pilots would have used their periscopes to locate a worthy target. At that point they were to surface and check their bearings and range to the target ship. This was when the Kaiten was most vulnerable to being detected on radar. After arming the warhead, the pilot dove and headed toward his target at maximum speed.

It is known that only two Kaitens were able to get close to their prey. Whether Nishina was one of them can never be confirmed, but he was the most experienced Kaiten pilot. One ship, the fleet oiler USS Mississinewa, loaded with volatile aviation fuel, was hit and sunk. The destroyer Case rammed another Kaiten and depth charges turned the lagoon into a boiling cauldron of foam. There were no more explosions. Mississinewa was the only victim of the new Kaiten. On Radio Tokyo the attack was a roaring success. Two big battleships had been sunk and carriers and cruisers damaged. The Kaiten would turn the heavens as they had been meant to do.

But well before the Kaiten threat had spread in the spring of 1945, U.S. destroyers and aircraft were hunting for the mother subs. And though Kaitens were fast and wakeless, they were noisy and easily heard on sonar.

The Ulithi attack group had been visited by the commander in chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Soemu Toyoda. That was an indicator of how seriously he regarded the Kaitens. The I-37 was ordered to Leyte Gulf to attack the fleet supporting the invasion. But she was spotted by the destroyers Conklin and McCoy Reynolds, which moved in for a sonar and hedgehog attack. None of the submarine’s 117 officers and crew survived, becoming the Kaiten first combat casualties.

The second wave was far larger and aimed at five U.S. anchorages. Ulithi was targeted, along with Manus, Guam, Hollandia in New Guinea, and Kossol Roads in Palau. On January 9, 1945, six submarines, each carrying four Kaitens, slipped out of Kure for what was intended to be a simultaneous attack. One of the subs was I-58. Lieutenant Commander Mochitsura Hashimoto, who would become infamous eight months later as the man who sank the cruiser Indianapolis in the Philippine Sea, saw little value in the new weapon. A torpedo expert, he probably saw the similarity between Kaitens and German Vengeance weapons like the V-2 rockets. They were little more than terror weapons with scant practical military value.

At Ulithi, I-47 launched four Kaitens but only succeeded in damaging the small transport Pontus. The destroyer Conklin sank the I-48 with all hands.

Of the four launched by I-36, one was detonated by depth charges dropped from a PBY Catalina flying boat of VP-21. The remaining Kaitens only managed to damage the Lassen-class ammunition ship Mazama and sink a landing craft. Eleven Americans died from these attacks.

Hashimoto’s I-58 launched all four Kaitens into Apra Harbor in Guam. One exploded immediately. As dawn rose, columns of smoke were visible in the distance. Hashimoto recognized the real flaw in the Kaiten project. Without communication between the Kaiten and the mother sub, there was no way to assess it. Time and again a mother sub could do little more than make a guess, usually wildly optimistic, at what its Kaitens had done.

Yet the high command continued to order more strikes. A third group of Kaitens left for Iwo Jima on February 20, 1945. First, I-44 was hunted for over two days until the submarine’s air was nearly unbreathable. She managed to slip away and returned to Japan. I-368 was sunk by a mine dropped from a Grumman TBF Avenger near Iwo Jima.

I-370 was depth charged by the destroyer Finnegan. All four Kaiten pilots died, along with I-370’s crew. Then a radar-equipped Grumman TBF Avenger with depth charges bombed I-368, sinking her with all hands.

Two more subs, I-58 and I-366 were sent to supplement the first attacks, departing Kure on March 10, but were recalled to base for a special operation called “Heaven One.” The mighty battleship Yamato and nine escorts were to leave Kure on April 6 and race south to attack the U.S. invasion fleet at Okinawa. The subs were to be ready to launch Kaitens in support. The I-47, still in the game, was bombed by Grumman Avengers and damaged. She was forced to head back to Kure for repairs.

Near Okinawa, five destroyers and the light carrier Bataan used depth charges to sink the I-56 with all hands and six Kaitens. One of the destroyers was USS Heermann, a survivor of the Taffy 3 fight at Samar in October.

Hashimoto was never able to get close to Okinawa due to sustained air attacks. After heading west and sending a report, he returned to Kure. By then Yamato and four of her escorts had been sunk with the loss of over 4,000 men.

Another group of Kaiten submarines left Kure on May 24 for Guam. I-36 saw a tanker and launched two Kaitens, but both missed. Firing four Type 95 torpedoes at the landing craft tender Endymion, I-36’s captain was shocked when all four exploded prematurely, possibly from being improperly set in the torpedo room. Endymion was damaged, but there was no further attack.

The Kaitens were not through with Guam. I-36 launched a single Kaiten at USS Antares, a general cargo ship. Antares was the ship that was towing a barge into Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941. Her crew spotted one of the midget submarines and alerted the destroyer Ward.

Antares fired on I-36 and called in the destroyer Sproston, which made a run on the submarine. The hasty launch of a Kaiten distracted the Sproston. The attack failed, but I-36 was able to escape with minor damage.

The last Kaiten raid left Kure on July 14, headed for the area east of Okinawa. Six submarines, including I-47 and I-58, were unable to launch any successful strikes. In the Philippine Sea, Hashimoto sank the USS Indianapolis—his only victory—with six Type 95 torpedoes, not the six Kaitens on board.

The only recorded sinking of a U.S. warship by a Kaiten was on July 24, east of Okinawa when I-53, carrying six Kaitens, was ordered to intercept a convoy. The destroyer escort Underhill altered course to avoid a mine—a dummy, launched by I-53 for just that purpose. Underhill’s sonar made several contacts, determined to be the sub and its Kaitens.

Underhill made a depth charge run that probably sank a Kaiten, but didn’t damage I-53. The ship rammed a second Kaiten, but was hit by a third, whose warhead erupted in a towering column of dirty water. The rammed then Kaiten exploded, sinking Underhill with more than half of her crew.

Two days after the second atomic bomb destroyed Nagasaki, I-366 launched two Kaitens at a convoy near Palau. Neither hit a ship, or even exploded.

On August 13, the surviving mother subs were ordered to return to base. Japan had surrendered. Between November 1944 and August 1945, at least 106 Kaiten pilots died attacking the U.S. Navy. Fifteen of those died in training accidents. Another 800 died in the sinking of eight mother subs. Unlike the kamikazes, the Kaiten was little more than a Japanese pipe dream. The human torpedoes sank only three U.S. ships. For every one American killed, four Japanese sailors died in the Kaitens and their mother subs.

Author Mark Carlson is a prolific writer on the topics of World War II and the history of aviation. He lives in San Diego, California.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments