By John W. Osborn, Jr.

The “few” who defended Great Britain in the sky during the days it stood alone against Hitler would have been hundreds fewer without the volunteers from outside the British Empire.

Many were flying fugitives from the Nazi occupations of their homelands. But also among them were a pocket-sized pilot, a shipwreck survivor, an Olympic champion, a blunt-talking cowboy, a washed-out, would-be aviator, and scores of others from a country then avowedly neutral in the war––the United States.

That Americans first flew and fought in World War II under a foreign flag was due to the efforts of another American well acquainted with fighting for a country other than his own.

Colonel Charles Sweeny had been expelled from West Point in 1900 for a hazing scandal, then embarked on an almost 40-year career as an international mercenary, from South American revolutions to the Spanish Civil War. While serving in the French Foreign Legion in World War I, Sweeny got to know fellow Americans in the Lafayette Escadrille and, when World War II came along, decided to form a new American flying group for the French.

U.S. law at the time prescribed possible jail time for foreign recruitment and loss of citizenship for service, so Sweeny had to organize a clandestine network. Vague notices or word-of-mouth at airfields around the country led to secret meetings in hotels, then a train ticket to Canada. Most recruits were stopped at the border by the FBI, but one who made it through was a pilot who compensated for his diminutiveness with sheer determination.

Just 4 feet 10 inches, Vernon Charles “Shorty” Keough was, in 1940, still a veteran barnstormer and one of the first skydivers, with over 500 jumps. He had just invested his life savings in a new airplane which a friend had promptly crashed. Recruited by Sweeny’s network in May 1940, Keough met two others in a Montreal hotel lobby who also got through: Eugene Quimby “Red” Tobin, an ex-Hollywood flier, and Andrew Mamedoff, from a White Russian family.

The trio would become inseparable, flying and fighting together, and dying within eight months of each other. A film director who got to know them in Britain described them: “Andy was massive and broad. A Russian type with pale blue eyes in a puckish Mongol face. Shorty was a dynamo with a shock of fair hair and an Irish temperament. Red was, perhaps, the most typical young American of the three. Tall and lanky, he had a grin that split the face in two, and a devastating vocabulary of wisecracks that was the delight of his friends and the despair of his seniors.”

The trio received a message instructing them to take the train to Halifax, Nova Scotia. At the train station they were met by a French agent who melodramatically led them through darkened backstreets and alleyways to an abandoned warehouse; inside he opened a safe to hand them money and boarding tickets on a tramp steamer bound for France.

In Paris, they were enlisted into the Armée de l’Air, then kept waiting while the Battle of France was being fought and lost. When finally sent to the front, without aircraft or even uniforms, it was too late to do much more than shelter in airfield ditches under Luftwaffe attack.

After France capitulated to the Germans, they headed for the coast by train and on foot, caught one of the last ships out, and landed in Plymouth, England. The American Embassy told them to go home, but they decided, instead, to join the Royal Air Force. As Tobin explained, “The way we figured it, the RAF ought to be willing to take us on. It looked as though they were going to need every pilot they could get before long.”

Tobin was right. Through an Englishwoman they had met on the boat across the Channel, Tobin, Keough, and Mamedoff received help in joining the RAF from a member of Parliament.

For all their tribulations, they had been preceded in the RAF, and in action, by a compatriot who had only to pull a few social strings. He would precede them in something else as well.

William Meade Lindsley “Billy” Fiske III came from a wealthy New England banking family and had twice driven a bobsled to victory in the Winter Olympics; he won gold as a 16-year-old in 1928 and again in 1932, but declined a third try when the 1936 games were held in Nazi Germany. When it became clear in the summer of 1939 that war was coming, he quit the family Wall Street firm and arrived in Britain by liner the day war was declared. While working in high finance in London, Fiske made many friends in the RAF Auxiliary.

With his social contacts, he had no trouble being allowed to join the RAF on September 18, 1939. “I can lay claim to being the first U.S. citizen to join the RAF,” he wrote, though adding, “My reasons for joining the fray are my own.”

He was assigned to RAF 601 Squadron, composed of his friends, and called the Millionaires’ Squadron (Fiske was fond of driving his green Bentley around the base), at Tangmere, July 10, 1940, just as the Battle of Britain was beginning. His skill on ice and snow well prepared him for the air. “Unquestionably Billy Fiske was the best pilot I’ve ever seen,” said the 601 commander.

A fellow 601 pilot said, “He was absolutely charming and completely natural. There was nothing forced or fake about him. That’s what endeared him to the whole squadron––pilots and ground crew.”

His service was to be tragically brief––just 28 days. On August 16, 1940, 601 Squadron was fighting a flight of German dive-bombers when a German gunner hit Fiske’s fuel tank and set it on fire. Instead of bailing out over the Channel, he made it back to base.

“I taxied up to it and got out,” Fiske’s flight commander later said. “There were two ambulancemen there. They had got Billy Fiske out of the cockpit. They didn’t know how to take off his parachute so I showed them. Billy was burned around the hands and ankles. I told him, ‘Don’t worry, you’ll be all right.’ Our adjutant went to see him that night. Billy was sitting up in bed perky as hell. The next thing we heard, he was dead. Died of shock.” He was 29 years old.

The first American in the RAF, Billy Fiske was the first to die in it––or so it was long thought. After the war it was discovered that another pilot, Jimmy Davis, killed six weeks earlier serving with 79 Squadron, was also American. Soon, other Americans would be risking their lives in the skies over Britain in that desperate summer and early autumn.

A week after Billy Fiske died, Shorty Keough, Red Tobin, and Andy Mamedoff reported for duty at 609 Squadron, based at RAF Yeadon, near Leeds. The commander, first seeing Keough, asked, “What is he, a mascot?”

“Mascot! I’m a pilot, you mug … I mean, sir,” Keough responded, quickly catching himself. He had to sit on cushions in his Spitfire, “though in the machine all you could see of him was the top of his head and a couple of eyes peering over the edge of the cockpit,” an RAF pilot said.

During the Battle of Britain, which lasted from July 10 to October 31, 1940, Red Tobin was credited with downing two fighters with a third probable, and a bomber, while Mamedoff and Keough jointly downed a bomber.

After one aerial contest, Mamedoff managed to bring his crippled Spitfire back to base. In another battle, Tobin blacked out in action over the Channel, then went into a dive, coming to just in time to pull up at 1,000 feet.

“When you come right down to it, flying a fighter in combat is just about the greatest game in the world––even if you are playing for keeps,” remarked Tobin. “You’re up there patrolling. Suddenly you sight those silver specks coming toward you from across the Channel. You hold them for an instant framed in the circle of your gunsight against a background of blue sky. You can’t help admiring the picture made by those 300 planes in tight formations. Then you remember those boys aren’t out for a ride and you start climbing to get above them. From then on, as the saying goes, you don’t have to be crazy, but it helps.”

Four other Americans fought in the Battle of Britain. One was Arthur Gerald Donahue, 64 Squadron, who fought for a week before being downed, bailing out with burns and injuries that required a lengthy recuperation. Hugh William Reilly, 66 Squadron, lasted a month in action before being killed on October 17, 1940, just two weeks before the Battle of Britain ended. Phillip Leckrone, 616 Squadron, flew a single sortie, helping down a German bomber.

Least distinguished of the Americans in the Battle of Britain was John Kenneth Haviland, 51 Squadron, who was the son of a U.S. Navy officer and an English mother. Thrown into combat without adequate training, he collided with another Hurricane on his first day in September 1940, managed to land, and did not fly again during the battle. He did serve with the RAF for the duration of the war, however.

Keough, Tobin, and Mamedoff flew for only a month with 609 Squadron. They were transferred to be among the very first Americans to fly as an organized unit in the RAF.

While Colonel Charles Sweeny was busy finding pilots for France, his namesake nephew was trying to convince the British to form a squadron of Americans, putting up $100,000 raised from wealthy friends and business associates to fund it. He made plain his reason: “The war could not be won without the assistance of the U.S., and I thought that everything that registered the effort of Americans in the war would help bring the U.S. in on the side of the Allies.”

With the FBI soon looking the other way (in November 1940, with the United States still officially neutral, the Justice Department announced it would not take action against the citizenships of Americans serving in the RAF), a committee run by artist Clayton Knight worked out of the Waldorf-Astoria Hotel in New York recruiting for service in Britain.

In contrast to the later Flying Tigers for China, drawn from the best Army and Navy pilots, what became the RAF’s “Eagle Squadrons” were all civilians, representing 63 professions, led by students (43) and pilots (19), including one self-listed “playboy.” Some were rejects for military service, such as the Eagles’ future commander, Chesley Peterson, turned down for the Army Air Corps for “inherent lack of flying ability.”

One of the oldest (at 38) of the Eagles, Harold Strickland, best summed up their reasons for going: “We were all motivated by the thought of high adventure, the excitement of combat flying, and a desire to help the British. I hesitate to use the word ‘romance,’ but it was there. It was the romance of the highest adventure, a sort of trademark among fliers everywhere. Adventure could have been found in any of the British armed services where thousands of Americans had volunteered, but we could fly.”

One American was so determined to be an Eagle that, stuck in Canada instructing, he deserted the RCAF for the RAF!

But no Eagle had a stronger reason for joining than James A. Goodson. Hehad been a passenger on the British liner Athenia, the first British ship to be sunk by a German U-boat in the war––on September 3, 1939.

The liner was crossing from Glasgow to Montreal when U-30 attacked. Athenia was carrying 1,103 civilians, including some 300 Americans, and 315 crew members. Of the 1,418 persons aboard, 98 passengers and 19 crew members were killed. Filled with a desire for vengeance, Goodson said later, “I felt an overwhelming fury that was to sweep over me time and time again during the war. No one had the right to cause such suffering to innocent people.”

The most important distinction between the Eagle Squadrons and the Flying Tigers was that, while the Tigers earned top mercenary wages of $600 a month for service and a $500 bonus for each downed Japanese aircraft, the Eagles received no more than standard RAF pay. But some questioned whether they were worth even that.

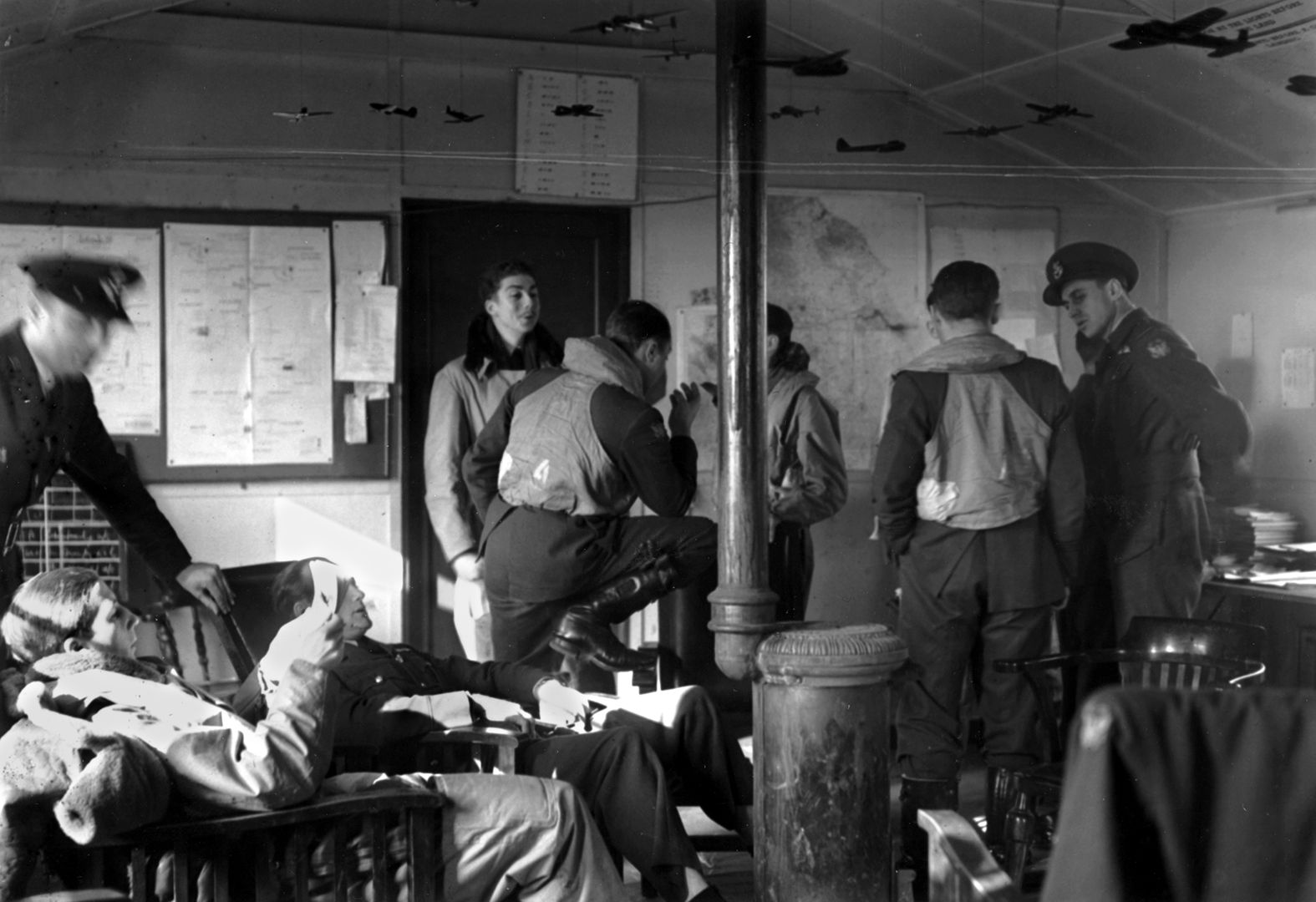

Founded in September 1940, 71 Eagle Squadron became operational on January 4, 1941 (two others, 121 and 133, would be established later). But, in training, the Eagles soon earned a serious reputation for lack of discipline––drinking, gambling, forgetting to salute or rise for a superior, letting their uniforms go to seed, and stunting with aircraft. An RAF air marshal openly called them “a bunch of prima-donnas.”

One, for a joke, pretended not to know who the king was when presented to him. Worst of all was Byron Kennerly. Finally sent home without seeing action for excessive drinking and public disturbances, he wrote a bogus memoir that was filmed by Hollywood (International Squadron, Warner Brothers, 1941) with no less than Ronald Reagan playing him!

Arthur Donahue quit the Eagles in disgust after a month to go back to flying with the British (he was killed in action in September 11, 1942). “They’re a mad bunch of Wild Westerners,” Colonel Sweeny, who had usurped his nephew’s role in founding the Eagles to be named as their honorary commander, told the British. “They need licking into shape and it’s no use of being easy with them just because they are Americans.”

In their first seven months of operations––air battles over the English Channel defending convoys, fighter sweeps over France, etc.––the Eagles’ only air “victory” was when a section leader accidentally shot up his wingman’s Hurricane while driving off a Messerschmitt; the wingman barely limped back to base but the Hurricane had to be scrapped.

First losses were “in accident” rather than in action––most tragically Shorty Keough. On February 15, 1941, he was flying to the defense of a convoy when he suddenly dived into the Channel. Faint hope for his survival had to be abandoned when size five flying boots were found amid floating wreckage. “Nobody but little Shorty could wear such small boots,” the Eagles’ record book reported sadly.

His friends Red Tobin and Andy Mamedoff did not long survive him. Tobin was killed in action on September 7, 1941; a month and a day later Mamedoff, just promoted to flight commander of the newly formed 133 Eagle Squadron and leading it to station in Northern Ireland, crashed in bad weather.

By that time, determined leadership had turned the Eagles into some of the best formations in the RAF. “I put it to them that if the Old Man thought we were prima donnas, why, let’s be the best prima donnas there are,” the Eagles’ commander, Chesley Peterson, said.

In October 1941, 71 Eagle Squadron, based at Kirton-in-Lindsey, north of Lincoln, led all RAF squadrons in kills, then repeated its standing in November. By year’s end, the Eagle Squadrons in total had a score of 45 confirmed kills, 151/2 probables, and 241/2 damaged. However, the Eagle who had most significantly contributed to the turn-around, their most colorful, outspoken, character, would see his achievements swept under the carpet for decades.

William R. Dunn was a cowboy and horse wrangler in Montana and Wyoming with the dream of emulating an uncle, a World War I flier. After receiving flying lessons from him, Dunn served in the U.S. Army from 1934 to 1937, trying without success to transfer to the Air Corps, even once going AWOL to find a unit.

Five days after Germany invaded Poland and World War II began, he took the train to Vancouver, British Columbia, to join the RCAF, only to be turned down. “I guess I came to Canada too quickly,” Dunn wrote in his memoir Fighter Pilot (1982). “Since I was broke, I decided my heroic potential might be of some benefit to the Canadian Army.”

He first joined the elite Seaforth Highlanders, a Scottish infantry regiment of the 3rd Brigade, 1st Canadian Division, then fought in France with a mortar unit. Evacuated back to England, he took over an antiaircraft gun after the crew was killed during a Luftwaffe raid on his camp, and downed two Stukas.

In October 1940, the RAF was scouring the other services for pilots with at least 500 hours of flying time. “My pencil may have slipped on my application form with my 160 [hours] sort of like 560,” Dunn wrote, with tongue in cheek.

Dunn joined 71 Eagle Squadron in April 1941, but “felt my reception was somewhat cool. Maybe it was because I’d been an enlisted man in the Canadian Army who had crawled from the muddy trenches into their blue heaven.”

Seeing an overtough squadron leader replaced “was the first I knew that we had a clique of any sort in the squadron––‘the fair-haired boys,’ we began to call them. Once I became aware of this clique, I could easily observe that they used political influence to gain promotions in rank and the new media for their ‘heroic’ war endeavors. Later, the more appropriate term ‘brown-nosers’ defined their activities. If you didn’t belong to their clique, you were cut out of the pattern and pushed into the background. I would soon encounter these ‘boys’ myself.”

After downing Luftwaffe aircraft from the ground, William Dunn then downed his first in the air while escorting British bombers near Lille, France, on July 2, 1941. “I saw an Messerschmitt 109E diving through the bomber formation at about 6,000 feet, squirting at the Blenheims as he dove. The 109 pilot made his break to port, right in front of me, maybe 70 or 100 yards away. I jammed the throttle wide open and, attacking the 109 from the port quarter, fired one burst of four seconds and three bursts of two seconds each. At about 50 yards range (the Hun kite filled my whole windscreen) I could see my machine gun bullets striking all over the German’s fuselage and wing-root. Then he began to smoke. I continued my attack down to 3,500 feet, again firing at point-blank range. Now the 109 began burning furiously, dived straight down to the ground, where it crashed with a hell of an explosion near a crossroad.”

It was, finally, the first air kill by an Eagle. But Dunn “ran head-on into our squadron’s ‘fair-haired boys’ clique.’” Another Eagle had downed a German fighter five minutes later and, “since I was not a member of the clique,” Dunn saw his kill downplayed in favor of the other pilot’s.

Dunn would achieve another aerial milestone for the Eagle Squadrons in another air battle near Lille on August 27, 1941: “I look around for a 109 that will give me a good target. In the previous months I had shot down four enemy aircraft. Now I needed one more victory to earn the coveted title of fighter ace. Just above the scrap I see two 109Fs that are evidently waiting for a shot-up Spitfire or Blenheim to drop out of the fight and try to get home. Then they’ll dive down and finish it off––easy meat.

“I climb fast behind and above the two Huns. I’m about 1,500 feet above them now, and I have the sun at my back. I give my engine full throttle and dive on the rearmost enemy aircraft. The German leader of the two sees me coming and quickly half-rolls onto his back, diving away from me. The second 109, my target, does a climbing turn to the left. I close the range to about 150 yards, line the Hun up in my gunsight, then I press the gun-firing button. My aircraft shudders as I hear the sharp chatter of eight machine guns. Acrid fumes of burned gunpowder fill my cockpit and sting my nostrils. I like this odor. It seems to stiffen my spine, tighten my muscles, make my blood race. It makes my scalp tingle, and I want to laugh.

“I see the grayish-white tracer streaks from my guns converge on the Messerschmitt’s tail section. The elevators and rudder disintegrate under the impact of the explosive DeWild bullets. Pieces fly off the enemy’s fuselage. The range is now down to 50 yards. Black liquid––engine oil––spatters my windscreen and a dense, brownish colored smoke is flung back at me. My enemy is finished. Splash one, but good! I’ve got my fifth victory.”

Dunn immediately added to his score, downing two more Me-109s, but, then, “I could see four 109s climbing up to intercept me. This is getting too hot for me. I jam the throttle through the gate, jerk the control column back into my stomach, and climb up and over them. The nearest takes a squirt at my fast-moving Spitfire. His deflection is bad, luckily. The 20mm cannon shells and machine-gun bullets streak past me and veer off my tail.

“I roll my Spit onto its back, pull on the stick, and the reversed horizon comes up to meet me. I hear explosions and a banging like hail on my fuselage. My port wing is hit again. I see splashing holes and rents send pieces flying off. A ball of fire flashes through the cockpit, smashing into the instrument panel. My right foot takes a heavy blow, bounces off the rudder pedal, and is numb. Two sharp blows bang into my right leg. Then comes a soft, deep darkness. I just faintly hear bits of broken glass and metal strike the cockpit floor.

“Fear grips me. It is finally happening to me … I am being shot down and killed!”

Dunn, close to unconsciousness, went into a dive. His head hitting the side of the cockpit hood roused him: “I raise my head and look through the windscreen towards the swirling fields of earth charging madly upward to enfold me. Suddenly I become conscious of my two hands tugging back on the control column. The nose of my Spitfire is slowly lifting. The land below me stops swirling as earth and sky return to their rightful places. The horizon reappears. My brain tells me that I live! I laugh without sound. I still own life!”

Dunn had pulled up at only 1,200 feet. Wounded, aircraft crippled, he struggled across the Channel at only 800 feet to an emergency landing in Britain.

To his continued frustration, Dunn returned from a month’s convalescence to learn two other Eagles had been awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, and one of them, considered more presentable for propaganda purposes, was being publicized as the Eagles’ first ace. “What about my victories––didn’t they count?” Dunn was to bitterly write. “It seemed as if my distinguished flying achievements had been purposely overlooked. After I got shot up and chucked in the hospital they decided to forget all about me. The DFC was normally awarded to a fighter pilot with five victories. I’m sure, but I can’t prove it, that Robbie, our intelligence officer, who was also a Member of Parliament and very influential at the Air Ministry, worked the DFC gongs for his two fair-haired boys. I never did get a silver DFC, just some bullet and cannon shells awarded from my German opponents.”

“On this note of discord,” as he called it, Dunn left the Eagle Squadron to take an instructor’s posting in Canada. By doing so, he remained in the RAF long after the other Eagles had left it.

Edwin Taylor was with 133 Eagle Squadron in Northern Ireland when the news of Pearl Harbor came over the radio: “I let out a yell that could be heard all the way to Derry…. That was the start of the bash to end all bashes––with unashamed tears running down their cheeks and patting each other on the back and buying drinks for each other.”

“We knew we had just gained a very powerful ally,” a squadron mate said, “and that in itself was reason to rejoice. We no longer stood alone.”

The next day, representatives from the Eagle Squadrons based in England were at the U.S. Embassy in London to request transfer to the American military. The process would drag on for 10 months, while the Eagles continued to fly their daily missions. Groups of them were sent to help defend Malta and Singapore, where James A. Campbell earned the unenviable distinction of being the only Eagle to be a POW of the Japanese.

The Eagle Squadrons’ last major action was in support of Operation Jubilee, the Canadian landing at Dieppe on August 19, 1942. “The air above Dieppe was thick with enemy and Allied aircraft,” recalled Barry Mahon, a section leader with 121 Eagle Squadron. He downed a Focke-Wulf diving for the landing boats, then, out of ammunition, was turning back for England to rearm and return when he “got a funny feeling and looked out. There was a yellow-nosed spinner about 200 feet below me and climbing. The FW had a better climbing ability than the Spitfire.”

Mahon tried to outclimb his opponent, but stalled out and dropped into the Focke-Wulf’s line of fire. “The noise was terrifying––like a thousand shot-puts all being thrown on a galvanized tin roof over your head. The gun panels ripped off my left wing. The engine exploded, and oil covered the cockpit, shells exploded on my right wing.”

Parachuting into the water, Mahon wrote, “I lay on my back in the dinghy and watched the tremendous air battle, probably the greatest air show the world had yet seen. There must have been 80 or 90 German planes and an equal number of British aircraft in a five-mile-square cube of the sky.

“The sights that morning and part of the afternoon were unbelievable. There would be a Spit being chased by a German being chased by a Spit being chased by a German, and the first three would be blown up, leaving the remaining one victorious until he turned into the guns of another opponent.

“[It was] a giant Fourth of July display, only much more ominous. The spent bullets were falling like hailstones, so hot they made a sizzling noise as they struck the water.”

Mahon finally drifted ashore, to be the only airman of some 3,000 Allied prisoners in the debacle––and the seventh Eagle––to be captured by the Germans. The Eagle Squadrons’ scores over Dieppe were nine confirmed, four probable kills, and 14 damaged; that brought the Squadrons’ final scores to 41 for 71 Squadron, 18 for 121 Squadron, and 141/2 for 133 Squadron.

A month later, on September 29, 1942, the Eagle Squadrons were inducted into the U.S. Army Air Forces as the Fourth Fighter Group (FFG) of the Eighth Air Force. The former Eagles were allowed to wear their RAF wings––the only American servicemen permitted to wear foreign insignia. The one-time service reject, Chesley Peterson, became, at 23, the youngest colonel in the USAAF.

The FFG went on to be the highest-scoring American unit in the European Theater, with 1,016 victories. The Athenia survivor, James A. Goodson, would be the group’s third-ranking ace with 30 victories, until he became one himself for a German pilot and was captured.

Losses among Americans serving in the RAF were heavy. Of the first who served in the Battle of Britain, only John Kenneth Haviland, who never joined the Eagle Squadrons, survived the war. He flew with the RAF for the entire war, earning a DFC, and was later Professor of Aeronautics at the University of Virginia. He died in July 2002.

Of the 244 serving in the Eagle Squadrons, 77 were killed flying with the RAF, then another 31 with the FFG, for a staggering loss rate of 44 percent.

After the war, Byron Kennerly, the former Eagle who did not face such risks, but fraudulently claimed he did, let his incorrigibility cross over into criminality and went to prison for bank robbery. He died in Los Angeles in 1967. Some Eagles continued with the Air Force, with Chesley Peterson and another Eagle retiring as major generals.

William Dunn went on his controversial way. He wanted to stay with the RAF, but “it was sort of implied that if I didn’t agree to a transfer, they’d come and get me.” He was transferred in June 1943 and finished the war flying in Burma as an acting lieutenant colonel. After being an “adviser” with Chiang Kai-Shek’s Nationalists in China, Dunn was unexpectedly denied permanent promotion to captain in the U.S. Air Force in 1949 and he was summarily discharged. He immediately re-enlisted as a sergeant, eventually seeing action in Vietnam, and finished with a career total of 378 combat missions.

On the day he finally retired, February 1, 1973, he was promoted in one jump from chief warrant officer to lieutenant colonel. At the ceremony he was also, finally, recognized by the Royal Air Force as both the first Eagle to down a German fighter and the first American ace of World War II.

Blunt as always, Dunn wrote in the aftermath of Vietnam: “I have been asked what I thought about young men who refused to serve in the military in the defense of our nation. My thoughts are expressed completely in the following statement: War is an ugly thing, but not the ugliest of things; the decayed and degraded state of moral and patriotic feeling which thinks that nothing is worth war is much worse. A man who has nothing for which he is willing to fight; nothing he cares about more than his own personal safety; is a miserable creature who has no chance of being free unless made and kept so by the exertions of better men than himself.”

One of Dunn’s “better men,” Billy Fiske, is memorialized on a plaque in the crypt below St. Paul’s Cathedral in London:

AN AMERICAN CITIZEN WHO DIED THAT ENGLAND MIGHT LIVE.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments