By Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

The “Charge of the Light Brigade,” a British cavalry action during the Battle of Balaklava in the Crimean War, 1854-1856, has been romanticized and immortalized, primarily through a ballad of the same name by Alfred, Lord Tennyson. The Charge was not, as considered by many, a great and glorious venture, but rather a tremendous military blunder, arguably caused by the fog of war and incompetent senior commanders.

Terry Brighton’s enthralling Hell Riders: The True Story of the Charge of the Light Brigade (John Macrae/Henry Holt, New York, 2004, 370 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography, index, $27.50, hardcover), was published to coincide with the Charge’s 150th anniversary. Brighton peels away the layers of myth that have accumulated around this fabled engagement, largely by using the words of those cavalrymen who charged into “the mouth of hell” and returned “thro’ the jaws of Death.” “My aim in writing Hell Riders,” writes Brighton, “has been to rediscover the full story of the charge as the survivors told it.”

Terry Brighton’s enthralling Hell Riders: The True Story of the Charge of the Light Brigade (John Macrae/Henry Holt, New York, 2004, 370 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography, index, $27.50, hardcover), was published to coincide with the Charge’s 150th anniversary. Brighton peels away the layers of myth that have accumulated around this fabled engagement, largely by using the words of those cavalrymen who charged into “the mouth of hell” and returned “thro’ the jaws of Death.” “My aim in writing Hell Riders,” writes Brighton, “has been to rediscover the full story of the charge as the survivors told it.”

The Cavalry Division was part of the Anglo-French expeditionary force that sailed to the Crimea in the spring of 1854. It consisted of the Heavy Brigade and the Light Brigade, with five light cavalry regiments—the 4th and 13th Light Dragoons, the 8th and 11th Hussars, and the 17th Lancers—in the Light Brigade. Brighton describes the composition of the regiment, use of cavalry weapons, and senior commanders. The Cavalry Division was commanded by Major General George C. Bingham, 3rd Earl of Lucan, and his despised brother-in-law, Brig. Gen. James T. Brudenell, 7th Earl of Cardigan, was the Light Brigade commander.

The Russians attacked the vulnerable British early on October 25, 1854, hoping to seize their supply port at Balaklava. Russian cavalry advances were repulsed by British infantry and by the Heavy Brigade of the Cavalry Division.

The entire situation that led to the Charge of the Light Brigade remains enshrouded in controversy. It seems an ambiguous attack order was given, relayed, and apparently misinterpreted. Brighton dissects the origin of the orders that led to the Charge, but does not ascertain responsibility for them. In the ensuing chaos, Cardigan gave the order to advance and led his men at a trot down the “Valley of Death.” The Light Brigade stoically continued its advance as its ranks were thinned by deadly Russian enfilading fire coming from the elevated flanks as well as the front. Cardigan courageously rode at the center of his brigade. As the advancing cavalry reached and hacked its way through the Russian guns, Russian horsemen were seen formed behind them. Cardigan turned around and rode back to the British lines. In a matter of minutes, the 666-man Light Brigade, according to Brighton, lost 110 men killed, 129 wounded and returned to the lines, and 32 wounded and taken prisoner, for a total of 271 casualties. More than 500 horses were killed or later destroyed.

The value of this book is in the 20 or so accounts of Charge survivors that are interspersed at relevant points throughout the narrative. The maps are quite excellent, and the illustrations include many of the usual Fenton photographs. Written for a popular audience, this study unfortunately contains no footnotes, which could have helped clarify controversial issues or provided references for corroboration and further research. There are also factual errors, including assertions about the purchase system, that detract from the book’s reliability. One appendix provides instructions for researching ancestors who may have charged with the Light Brigade, and a second appendix contains a by-name roll of Light Brigade members at Balaklava.

The Charge of the Light Brigade, according to many sources, was not a romantic and heroic assault against overwhelming odds, but an unnecessary bungle that destroyed the effectiveness of the Cavalry Division for the remainder of the war. Brighton, however, believes that “in terms of assumed objective”—to take the Russian guns visible at the far end of the valley—“it was an astounding success.” While even the outcome of the Charge remains contentious, there is no doubt, in the words of Captain Robert Portal, 4th Light Dragoons, that during the Charge “shells fell like hail all around us, … which whistled through our ranks, dealing death and destruction.”

Recent and Recommended

Atlas of the Civil War, by Steven E. Woodworth and Kenneth J. Winkle, Oxford University Press, New York, 2004, 448 pp., illustrations, maps, tables, glossary, chronology, bibliography, index, $75.00, hardcover.

This mammoth volume, Atlas of the Civil War, is an outstanding work in every way. It is divided chronologically into chapters by year of the war, from 1861 to 1865 inclusive. Each chapter includes a narrative introduction, and all of the year’s military and naval operations, in all theaters, are connected by a similarly well-written narrative. The first chapter contains a mind-boggling amount of information pertaining to the United States during the decades leading up the Civil War, presented in easy-to-understand and clear maps, graphs, and charts. This information includes territorial expansion, emancipation, pre-war politics, elections of 1852 and 1856, spread of slavery, immigration, farmland by value, agriculture, cotton, railroad construction, secession, federal and Confederate finances, arms production, and more. These show that the war was a component of, and not fought in isolation from, society.

The hundreds of color maps depict manmade and natural features, headquarters and unit locations and dispositions, troop movements and operational phases, and related information on Civil War battles and campaigns. The coffee table-sized Atlas of the Civil War definitely “offers the clearest and most comprehensive examination of the war that transformed America, surpassing the scope of any previously published single-volume work.”

In Brief

In Brief

The Battle of Salamis: The Naval Encounter That Saved Greece—and Western Civilization, by Barry Strauss, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2004, illustrations, maps, notes, sources, index, $25.00, hardcover.

Barry Strauss is professor of history and classics at Cornell University and a recognized authority on ancient warfare. In this finely crafted study, Strauss chronicles the tremendous Persian-Greek naval clash at Salamis in September 480 B.C. Earlier that year, a huge Persian army, accompanied by a fleet of about 1,500 warships and 3,000 transports, invaded Greece. As the Persian and Greek fleets fought an indecisive engagement at Artemisium, Leonidas and his stalwart Spartans failed to stop the Persian advance at Thermopylae. In September, after the Persians occupied Athens, Themistocles, the Athenian leader, feared the numerically superior Persian fleet would blockade and destroy the Athenian navy. Through “a combination of cunning and deceit,” the heavier Greek triremes (ships with three levels of rowers) attacked the larger Persian fleet in the narrow channel, where maneuver was limited. In a seven-hour battle, about half the 400 or more Persian ships were sunk, while the Greeks lost only about 40 ships. Strauss reconstructs this decisive naval battle largely through the writings of Herodotus and other classical authors, combined with more recent studies. This is an action packed and adventure filled “dramatic story of the maritime engagement that routed the Persian Empire and made possible modern democracy.”

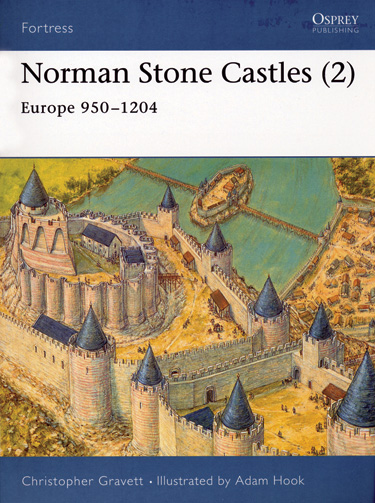

Norman Stone Castles (2): Europe, 950-1204, by Christopher Gravett, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, illustrations, maps, chronology, bibliography, index, $21.95, softcover.

Norman Stone Castles (2): Europe, 950-1204, by Christopher Gravett, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, illustrations, maps, chronology, bibliography, index, $21.95, softcover.

“The Duchy of Normandy was created in 911 by King Charles the Simple of France,” writes Christopher Gravett, “to accommodate the Scandinavian followers of the Viking leader, Rollo.” This new territory was called “Normandy,” the land of the Northmen, or Normans. It was here that the Normans were introduced to the castle, then a recent development for fortifying homes and other threatened areas and a potent symbol of feudalism. Originally built of earth and timber, stone castles soon appeared in Normandy and, in the 11th century, in southern Italy and Sicily where the Normans migrated. This superb book covers the design, development, and principles of defense of Norman castles. Daily life in these castles, during peace and war, is also chronicled. A pictorial tour of the castle Chateau-Gaillard is provided, as is information on the fate of the castles and visiting these fortified sites today. Anyone interested in military fortifications will want this outstanding book, which has excellent photographs, detailed illustrations, helpful maps, and cutaway artwork.

A Proper Sense of Honor: Service and Sacrifice in George Washington’s Army, by Caroline Cox, University of North Caroline Press, Chapel Hill, 2004, 338 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $37.50, hardcover.

A Proper Sense of Honor: Service and Sacrifice in George Washington’s Army, by Caroline Cox, University of North Caroline Press, Chapel Hill, 2004, 338 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $37.50, hardcover.

This is an intriguing, innovative, and ambitious study. Historian Caroline Cox examines the creation and composition of the Continental Army during the “Tumults & Commotions” of the American Revolution. She notes accurately that, “the unthinking decision to divide the army into officers who were gentlemen and soldiers who were not reflected a central division in colonial and British society.” Cox, after assessing the attitudes and expectations of the officers and soldiers of the fledgling Army, outlines the manifestations of the hierarchically structured military force. These differences included the application of military discipline and punishments, medical care, and burial. The Continental Army came into existence during a period of tremendous political and social turmoil. It was much more egalitarian than its European counterparts, and the American officers and men, despite social and other differences, were generally motivated and united by a common goal and sense of purpose. This scholarly treatise provides a glimpse into the military culture and class structure of the new American Army.

The Alamo, by Frank Thompson, University of North Texas Press, Denton, 2005, 128 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $24.95, large format softcover.

The Alamo, by Frank Thompson, University of North Texas Press, Denton, 2005, 128 pp., illustrations, maps, bibliography, index, $24.95, large format softcover.

The heroic defense of the Alamo in 1836 is one of the most dramatic episodes in Texas history. Frank Thompson, a filmmaker and author of two earlier Alamo-related books, emphasizes that, “millions, throughout history, have been inspired by the idea that a vastly outnumbered group of men so believed in the ideals for which they were fighting that they willingly laid down their lives for those ideals.” The events leading up to, the actual siege and battle of the Alamo, and their aftermath, are chronicled in a straightforward manner. A key theme of this fine study is how the battle, its meaning, and the reputations of the Alamo defenders have evolved over the decades and grown to mythic proportions. This superb book is highly recommended, mainly because of its numerous, excellent, and provocative illustrations.

Glory Was Not Their Companion: The Twenty-Sixth New York Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War, by Paul Taylor, McFarland, Jefferson N.C., 2005, 231 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, appendices, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover.

Glory Was Not Their Companion: The Twenty-Sixth New York Volunteer Infantry in the Civil War, by Paul Taylor, McFarland, Jefferson N.C., 2005, 231 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, appendices, bibliography, index, $45.00, hardcover.

The 26th (not Twenty-Sixth) New York Volunteer Infantry was one of almost 300 infantry regiments organized by the Union that fought in the Civil War. The 26th consisted largely of citizens from the Oneida County area of central New York State. It was initially mustered into Federal service on May 17, 1861, for 90 days, a term of service later extended to two years. Author Paul Taylor has done a fine job of historical detective work in finding and using the scant documentation and records left by this unit and its soldiers. As a result, the reader can follow the 26th from New York to Washington, D.C., where it spent many months defending the nation’s capitol. The regiment fought at Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Chancellorsville before being mustered out of service in 1863. The 26th was frequently in the thick of hard-fought battles, but “victory was usually absent and glory was not their companion.” Containing the stories of individual officers and soldiers, as well as a roster of the 1,182 men who served in the 26th, this fine book will appeal to Civil War enthusiasts and military genealogists.

Co. Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War, by Sam R. Watkins, Touchstone Book/Simon & Schuster, 2003, 240 pp., index, $13.00, softcover.

Co. Aytch: A Confederate Memoir of the Civil War, by Sam R. Watkins, Touchstone Book/Simon & Schuster, 2003, 240 pp., index, $13.00, softcover.

Co. Aytch is the excellent Civil War memoir of Private Sam R. Watkins, who served in Company H, 1st Tennessee Regiment, Confederate States Army. “It is safe to say,” notes Roy P. Basler in the Introduction, “that no American soldier since the Civil War fought so long and so hard: Shiloh, Corinth, Murfreesboro, Shelbyville, Chattanooga, Chickamauga, Missionary Ridge, the Hundred Days Battles, Atlanta, Jonesboro, Franklin, Nashville.” This compelling narrative was written after the war and published serially in Watkins’ hometown newspaper, the Columbia, Tenn., Herald, in 1881-1882. While it has since been republished, until this Touchstone edition, in a few limited editions, it retains a sense of immediacy, poignancy, and detail. During a freezing winter in the Virginia mountains, for example, Watkins recalled arriving at a guard post: “Some were sitting down and some were lying down; but each and every one was as cold and as hard frozen as the icicles that hung from their hands and faces and clothing—dead!” Watkins shed light on the battles he fought in, his leaders, and the conditions of soldiering in the Confederate Army, and reflects on Southern society and its system: “Our cause was lost from the beginning.”

Collapse at Meuse-Argonne: The Failure of the Missouri-Kansas Division, by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2004, 160 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, sources, index, $29.95 hardcover.

Collapse at Meuse-Argonne: The Failure of the Missouri-Kansas Division, by Robert H. Ferrell, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2004, 160 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, sources, index, $29.95 hardcover.

The 35th Division, consisting largely of National Guardsmen from Missouri and Kansas, veritably disintegrated as a fighting unit early in the Meuse-Argonne offensive during World War I. Historian Robert H. Ferrell, the author or editor of many previous worthwhile World War I studies, dissects the organization, training, and leadership of the 35th Division to determine why it failed in combat. The Meuse-Argonne offensive began on September 26, 1918. The American First Army attacked with three corps abreast, with each corps having three divisions on-line and one in reserve. The 35th Division was on the right flank of the western-most I Corps. Within five days, the 35th Division suffered about 7,000 casualties, was disorganized, declared combat ineffective, and replaced by the 1st Division. Ferrell shows that there was inadequate unit training, a number of senior commanders were replaced only days before the offensive began, and communications and coordination were poor. There was also considerable friction between regular Army officers (mainly West Point graduates) and National Guard leaders (one of whom was Captain Harry S. Truman of the 129th Field Artillery Regiment). Ferrell’s study is a model of clarity and analysis of unit combat effectiveness.

In Hitler’s Bunker: A Boy Soldier’s Eyewitness Account of the Fuhrer’s Last Days, by Armin D. Lehmann with Tim Carroll, Lyons Press, Guilford, Conn., 2004, illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

In Hitler’s Bunker: A Boy Soldier’s Eyewitness Account of the Fuhrer’s Last Days, by Armin D. Lehmann with Tim Carroll, Lyons Press, Guilford, Conn., 2004, illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

“I was a fanatical Nazi. I was devoted to Hitler,” writes Armin D. Lehmann, and “I would have died for him, and I nearly did, several times, as a fighter against the Red Army and as a courier in the last days of his life.” Lehmann, born in Lower Silesia in 1929, became a zealous member of the Hitler Youth. In 1945, during the final months of the titanic struggle of World War II, he fought against the advancing Soviets. As a result of his bravery, Lehmann was selected to be a courier for Artur Axmann, the Hitler Youth leader, in Hitler’s bunker beneath the Chancellery in Berlin. He attended Hitler’s 56th birthday and reportedly met the Fuhrer face-to-face, writing, “I could not believe my eyes that this withered old man in front of me was the visionary leader who had led our nation to greatness.” While Lehmann’s narrative is certainly riveting, he could not personally have known, seen, or heard everything that he claims to. Lehmann could not have known how Hitler reacted in various meetings, what Goering’s thoughts were, or the private conversations of Nazi luminaries. Co-author Tim Carroll states that Lehmann’s “memories do not always coincide with established history.” While fast-paced, this book has significant accuracy and factual problems and seems more like a good story than good history. n

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments