By Mark Simmons

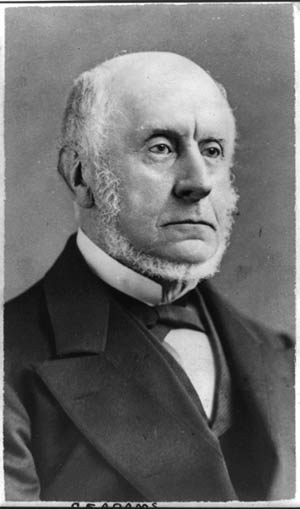

In November 1861, word swept through London that an American warship, James Adger, in port at Southampton, was planning to put to sea and intercept a British ship bringing Confederate emissaries to Europe. As a result, the American minister to Great Britain found himself summoned to see the British prime minister at his residence at 94 Piccadilly. Charles Francis Adams made his way through the yellow gloom of a London fog and found Lord Palmerston waiting for him in the library. Palmerston immediately complained to Adams that Adger’s captain and crew, while “enjoying the hospitality of this country, filling his ship with coals and other supplies, and filling his own stomach with brandy should, within sight of the shore, commit an act which would be felt as offensive to the national flag.”

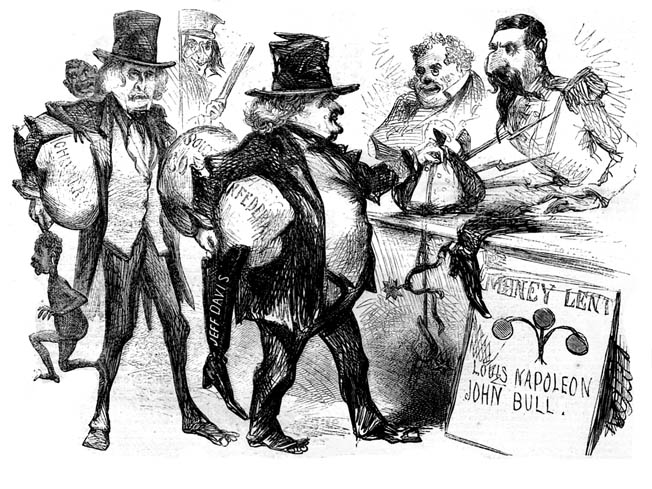

Earlier in the year, President Abraham Lincoln had proclaimed a blockade of Southern ports, after which Great Britain and France commenced a policy of neutrality that carried with it the rights of belligerent action by the Confederacy. It was the only important concession made to the Confederate states by European powers during the war. The Confederate commissioners in Britain at that time were a poor lot, while the United States foreign minister, Adams, the son of former President John Quincy Adams, was a skilled diplomat who had been urged by Secretary of State William H. Seward to be bold in asserting American rights.

Confederate diplomacy in Europe was more complacent, based on a belief in the economic power of “King Cotton” upon which British and French mills were dependent. Confederate President Jefferson Davis subscribed to this view. Prior to the war, England and Europe had imported nearly 85 percent of their cotton from the South. Nearly one-fifth of the British population earned its livelihood from the cotton industry, while one-tenth of Britain’s capital was invested in cotton as well. However, there was no official Confederate policy to produce a phony cotton famine in Europe or rush cotton abroad to fill the coffers of the South. It would be a short war, in Davis’s view. If it lasted longer, a concomitant cotton famine would inevitably bring Great Britain into the war to safeguard her economic interests and rescue the South.

Mason and Slidell: The Confederacy’s European Diplomats

William L. Yancey had resigned as Confederate envoy to Britain. In his place, Davis assigned a pair of trusted political cronies to represent Southern interests in London and Paris. James M. Mason, Yancey’s replacement, was a strange choice in the view of well-connected political wife Mary Boykin Chesnut, who wrote in her diary: “My wildest imagination will not picture Mr. Mason as a diplomat. He will say ‘chaw’ for ‘chew’ and he will call himself ‘Jeems’ and he will wear a dress coat to breakfast. Over here whatever a Mason does is right. He is above the law.” His Paris-based associate John Slidell was a better choice. Slidell was a skilled politician and sophisticated New Yorker who had married a French-speaking Creole and moved to New Orleans.

In October, Mason and Slidell were in Charleston waiting to run the blockade aboard CSS Nashville, a fast steamer heading directly for England. However, Nashville had a deep draft and could only use one of Charleston’s channels, which were heavily guarded by Union warships. The diplomats booked passage on Gordon, a ship chartered for $10,000 by George Trenholm, who ran a cotton brokerage, finance, and shipping firm, with offices in Liverpool. The Fraser, Trenholm Company did much of the banking for the Confederacy in Great Britain. The shallow-draft Gordon, renamed Theodora to confuse Union blockaders, could use any channel; she left Charleston at 1 am on October 12 and easily evaded the blockade. “Here we are,” Mason wrote gleefully, “on the deep blue sea, clear of all the Yankees. We ran the blockade in splendid style.”

Two days later the diplomats arrived in Nassau but missed their connection with a British steamer. They turned for Cuba, hoping to find a British mail ship bound for England. Arriving in Cuba on October 15, they found that British mail ships did dock at Havana but that they would have to wait three weeks for the next ship, RMS Trent.

The Union’s Hunt For the Diplomats

Union intelligence sources thought Mason and Slidell had escaped aboard Nashville. Thus the U.S. Navy dispatched James Adger, commanded by John B. Marchand, with orders to intercept Nashville. On October 3 the Union steam frigate San Jacinto, commanded by 62-year-old Captain Charles D. Wilkes, arrived at St. Thomas in the Danish West Indies. He was hunting the Confederate raider CSS Sumter.

Wilkes, a gifted astronomer, had experienced many ups and downs in his naval career. Early on, he had won accolades for his voyages of discovery to Antarctica and the Fiji Islands. But repeated displays of bad temper and insubordination had landed him in hot water with his superiors, and Wilkes had been shunted aside to a minor bureaucratic desk in Washington before receiving orders to take command of the steam warship San Jacinto on patrol off the coast of West Africa. He was directed to sail the ship home for refitting. Characteristically disobeying orders, Wilkes determined instead to prowl the West Indies for Rebel shipping.

In Cienfuegos, on the southern coast of Cuba, Wilkes learned from a newspaper that Mason and Slidell were in Havana waiting to take passage on Trent, sailing first for St. Thomas and then on to England. Wilkes knew that Trent would have to use the Bahama Channel between Cuba and the Great Bahama Bank. He thought over the legal implications of trying to remove the Confederate envoys from the British vessel, asking the opinion of his executive officer, Lieutenant D.M. Fairfax. He decided that Mason and Slidell could be considered “contraband” and legally seized.

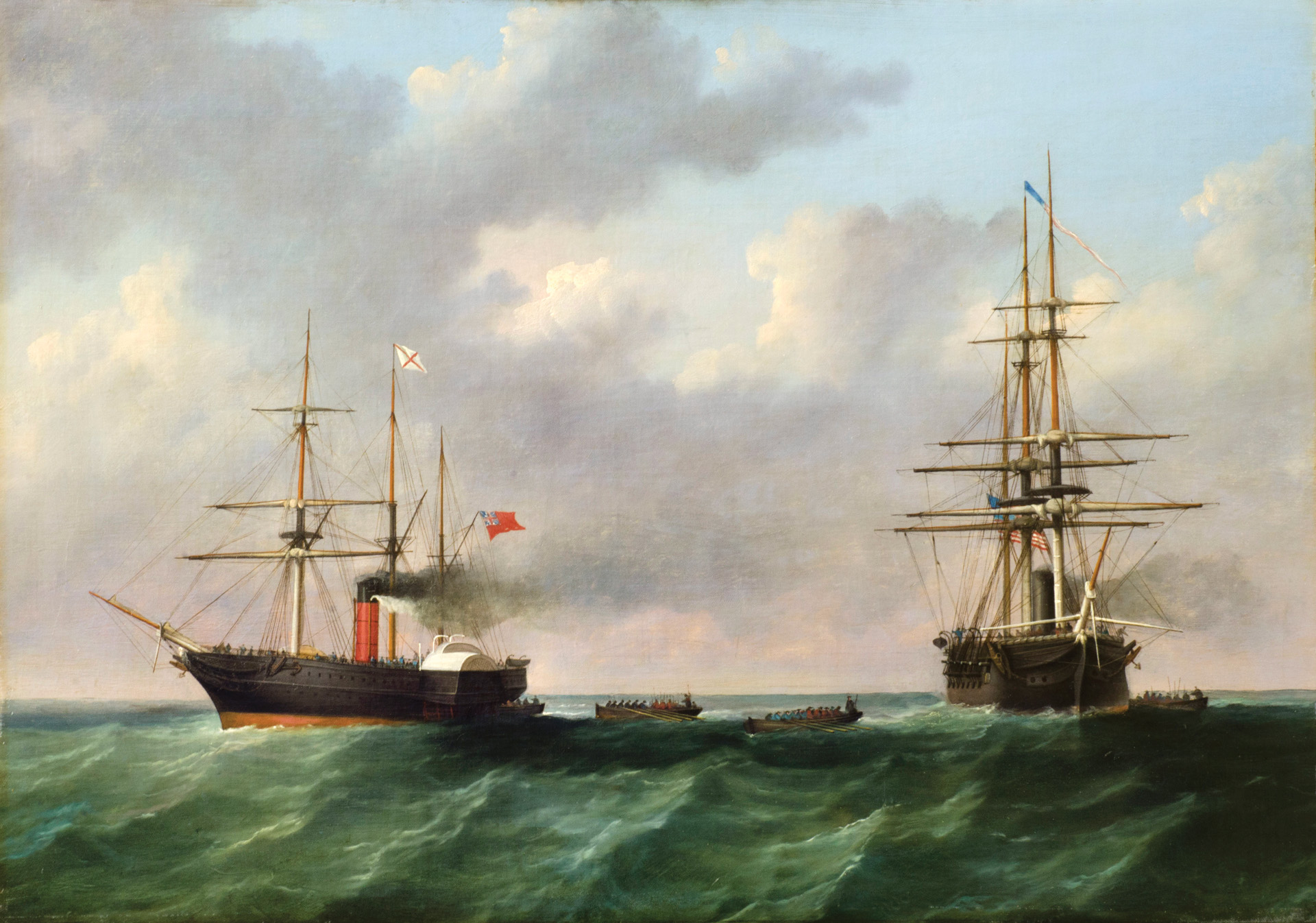

Boarding the RMS Trent

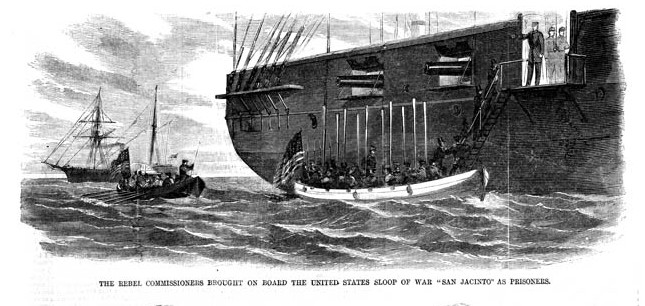

Trent left Havana on November 7 with Mason and Slidell on board; Slidell was accompanied by his wife and children. Diplomatic secretaries James E. Macfarland and George Eustis were also part of the official company. Passing through the Bahama Channel they found San Jacinto waiting. The Federal ship spotted Trent about noon on November 8; the mail ship was flying the Union Jack. Wilkes ordered a shot fired across Trent’s bow. It was ignored. A second shot landed close to the bow. Trent hove to. Wilkes gave detailed instructions to Fairfax. “Should Mister Mason, Mister Slidell, Mister Eustis and Mister Macfarland be on board,” he said, “make them prisoners and send them on board this ship immediately and take possession [of the Trent] as a prize.” Fairfax was also instructed to seize any dispatches and official correspondence he might find.

Armed with cutlasses and pistols, Fairfax and a boarding party of 20 men approached Trent in two cutters. Fairfax boarded alone, not wishing to enflame the situation, but found Captain James Moir furious that his ship had been stopped at sea. Fairfax told him his orders, Moir refused to cooperate, and Fairfax soon found himself surrounded and threatened by passengers and crew. He had little choice but to order the armed party in the waiting boats to join him. Once again Moir refused permission for the boarding party to search the ship. Mason and Slidell came forward willingly, and Fairfax backed down, belatedly realizing that such a search would constitute a de facto seizing of the ship—a clear act of war.

Mason and Slidell formally refused to go with Fairfax but did not resist when led to the boats. Wilkes had hoped to find important documents in the captured men’s luggage but found nothing. All their dispatches had been taken in hand by Trent’s mail agent, Richard Williams, who promised to deliver them to Confederate authorities in London. In the meantime, Slidell’s furious wife and daughters heaped verbal abuse on the Union sailors, even after Fairfax grabbed one of the daughters and saved her from falling overboard after a sudden wave.

Mixed Reactions in the North About the Capture

Wilkes was still keen to seize Trent, but Fairfax talked him out of it. A prize crew would be needed, he warned, and the inconvenience to Trent’s other passengers and mail recipients was unacceptable. Wilkes reluctantly agreed, and Trent was allowed to proceed on her way. Meanwhile, San Jacinto reached Hampton Roads on November 15 for coaling, and Wilkes was able to contact Washington. He was ordered on to Boston, where his captives were imprisoned in Fort Warren. A congratulatory telegram was waiting for Wilkes from Secretary of the Navy Gideon Welles. “Your conduct in seizing these public enemies was marked by intelligence, ability, decision, and firmness, and has the emphatic approval of this Department,” Welles informed him.

Others in the North likewise praised Wilkes and his crew. Congress thanked him for his “brave, adroit and patriotic conduct in the arrest of the traitors” and had a gold medal struck for him. He was the toast of Boston and celebrated throughout the country as a hero of the republic. The New York Times stoked the patriotic fervor. “We do not believe the American heart ever thrilled with more genuine delight than it did yesterday, at the intelligence of the capture of Messrs. Slidell and Mason,” the newspaper reported. To a Northern public conditioned to believe that Great Britain was decidedly pro-Confederate, the Trent affair seemed like a perfect way to put the haughty Britons in their place.

However, others in the North worried that Wilkes’ actions were identical to those that had led the United States to go to war with Britain in 1812. Now the roles were reversed. At midday on November 27, news of the seizures reached London, where it was greeted with personal and official fury. Pro-Northern politician John Bright described the public mood as “every sword leaping from its scabbard, and every man looking about for his pistols and blunderbusses.” Benjamin Moran, assistant to Adams at the American legation, wrote in his diary, “The people are beginning to see that their flag has been insulted, and if that devil The Times feeds their ire tomorrow, as it assuredly will, nothing but a miracle can prevent their sympathies running to the South and Palmerston getting up a war. The Times is filled with such slatternly abuse of us and ours that it is fair to conclude that all the fishwives of Billingsgate have been transferred to Printing House Square.”

The British Response

Adams was not at the legation when the news arrived. He was in Yorkshire in the north of England enjoying the hospitality at Fryston Hall as the guest of socialite-politician Richard Monckton Milnes. Moran sent a panicky message to Adams, but the veteran diplomat did not feel the need to hurry back. Finally returning to London, Adams found a note from Foreign Secretary Lord Russell on his desk, but it was late in the day and Adams responded that he would see him the next day. He found his British counterpart with “a shade more of gravity visible in his manner, but no ill will.” The meeting lasted a mere 10 minutes, Adams recalled, but “I scarcely remember a day of greater strain in my life.” What had been feared might happen with James Adger had come to pass with San Jacinto. Adams doubted that two Confederate envoys were all that important.

In Richmond, Jefferson Davis sent a message to Congress condemning the Federal actions as a violation of international rights “for the most part held sacred even amongst barbarians.” But the Davis administration failed to exploit the incident as a good propaganda opportunity. Mary Chesnut wrote about the seizure of Slidell and Mason, perhaps reflecting the general view in the South. “Something good is obliged to come from such a stupid blunder. The Yankees must bow the knee to the British, or fight them. As I read the Northern newspapers, the blood rushes to my head. Anyhow, down they must go to Old England, knuckle on their marrow bones, to keep her on their side—or barely neutral.”

The British cabinet met in emergency session. Palmerston angrily threw his hat onto the Cabinet Room table and told his colleagues, “I don’t know whether you are going to stand this, but I’ll be damned if I do.” He wrote to Queen Victoria a few days later, saying he wanted to teach the United States a lesson. He left the door open for diplomacy: “If, however, the Americans were to climb down and apologise the result would be honourable for England and humiliating for the United States.”

Recent dispatches from Lord Lyons, British ambassador to the United States, were read at the meeting. Lyons warned that American Secretary of State Seward might provoke an incident and that the United States then would have difficulty in climbing down. He recommended a show of force, including reinforcing the garrison in Canada. Lord Somerset, the First Lord of the Admiralty, was against Palmerston’s wish to reinforce Rear Admiral Sir Alexander Milne’s North American and West Indies fleet, arguing that Milne already had enough ships superior to those of the United States and that there was no point incurring unnecessary expense.

However, on land it was a different matter. Within a week of the Trent crisis, Secretary of War Sir George Lewis proposed sending 30,000 men to Canada. Palmerston told the Secretary of State for the Colonies, the Duke of Newcastle, to advise the Governor General of Canada to prepare for war. “Such an insult to our flag can only be atoned by the restoration of the men who were seized,” said Palmerston, “and with Mister Seward at the helm of the United States, and the mob and the press manning the vessel, it is too probable that this atonement may be refused.”

This view had support in both the Houses of Commons and Lords. The country was clamoring for war. All concurred that the American seizure was unlawful. However, at the November 19 cabinet meeting the ministers could not agree on the response they should make to the Americans. William Gladstone, Chancellor of the Exchequer, argued that too strong a response would leave the Americans no room to maneuver. Palmerston countered that too weak a response would give the United States the wrong impression of Great Britain’s resolve. It was decided to leave the drafting of the letter to Foreign Secretary Lord Russell. Russell’s letter stated the facts of the case and demanded the restoration of the Confederate commissioners and a formal apology within seven days of receiving the letter. Failure to comply would mean the immediate departure of Lord Lyons to Canada and a de facto state of war between the two nations.

The cabinet reconvened the next day to examine Russell’s draft letter. Some felt the meaning was unclear, and Russell became defensive. Finally, it was agreed that Lord Lyons would be sent two letters—the first a basic outline of the case, the second containing the threat of war within seven days. Gladstone began backtracking, saying he was not even sure the law was on their side, even though there was no doubt that Wilkes had violated international law. After long hours of debate, the cabinet officers agreed to send the letters to the queen for her approval.

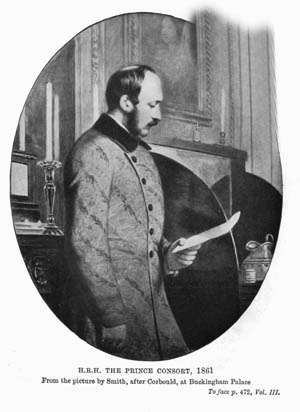

The Last Act of Prince Albert

The letters arrived at Windsor Castle on November 30. Prince Albert, the German-born consort and husband of Queen Victoria, had been kept up to date with the cabinet’s deliberations, and he was convinced that their reaction would be overly aggressive. Prince Albert was ill at the time; officially, he was said to be suffering from a chill, but in fact he had a serious case of typhoid fever. Yet he dragged himself from his bed, barely able to hold a pen, and amended the proposed text. He felt that there should be “the expression of hope that the American captain did not act under instructions, or if he did, that he misapprehended them—that the United States Government must be fully aware that the British Government could not allow the flag to be insulted, and the security of her mail communications be placed in jeopardy, and Her Majesty’s Government are unwilling to believe that the United States Government intended wantonly to put an insult upon this country … and that we are therefore glad to believe that they would spontaneously offer such redress as alone could satisfy this country, viz: the restoration of the unfortunate passengers and a suitable apology.”

It was a loophole, an exit route that would allow the American government to withdraw with honor. This redrafting by Prince Albert was the last service he performed for his adopted country. When he presented the document to the queen for her signature, he complained, “I feel so weak I have hardly been able to hold my pen.” He collapsed the next day and died 12 days later at the age of 42. Victoria mourned him for the rest of her lengthy life, always wearing widow’s black.

Lord Russell agreed with the prince’s additions and changes but still doubted that Seward would climb down. He composed a third letter to Lyons outlining the presentation of Her Majesty’s demands. Above all, the Confederate commissioners must be released from prison. No apology would appease Britain if they were kept in custody. There was to be no bargaining on that point.

An Export Ban on the United States

The next day Captain Conway Seymour boarded the Boston-bound Europa with the British government’s letters. Even with reasonable weather it would still take the letters 12 days to reach Lyons and another 12 to return. Meanwhile, Russell worried that the Americans would prevaricate. He wrote, “I cannot imagine their giving a plain yes or no to our demands, I think they will try to hook in France and if that is, as I hope, impossible, to set Russia to support them.” Palmerston, for his part, doubted that the United States would even bother to negotiate. “The masses make it impossible for Lincoln and Seward to grant our demands,“ he said, “and we must therefore look forward to war as the probable result.”

While British diplomats fretted and fulminated, Southerners watched the looming crisis with glee. As one observer noted, most Confederates “rejoiced in the prospect of retaliation by England” against the Federal government. The Richmond Enquirer editorialized against Wilkes, charging that he had “violated the rights of embassy, long held sacred, even among barbarians.” The Confederacy seemed on the verge of gaining a valuable ally in the war against the North and official recognition by European powers that it so desperately sought. “The opinion now prevails,” wrote a Confederate envoy in London, “that there will be war. England will have a vast steam fleet upon the American coast and will sweep away the blockading squadrons from before our ports.”

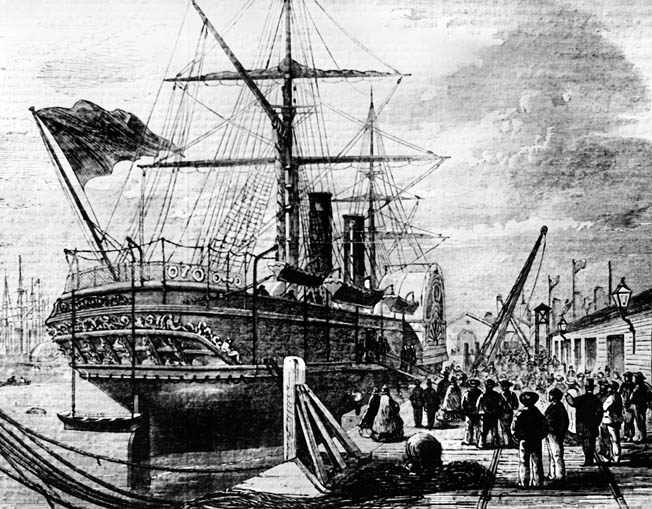

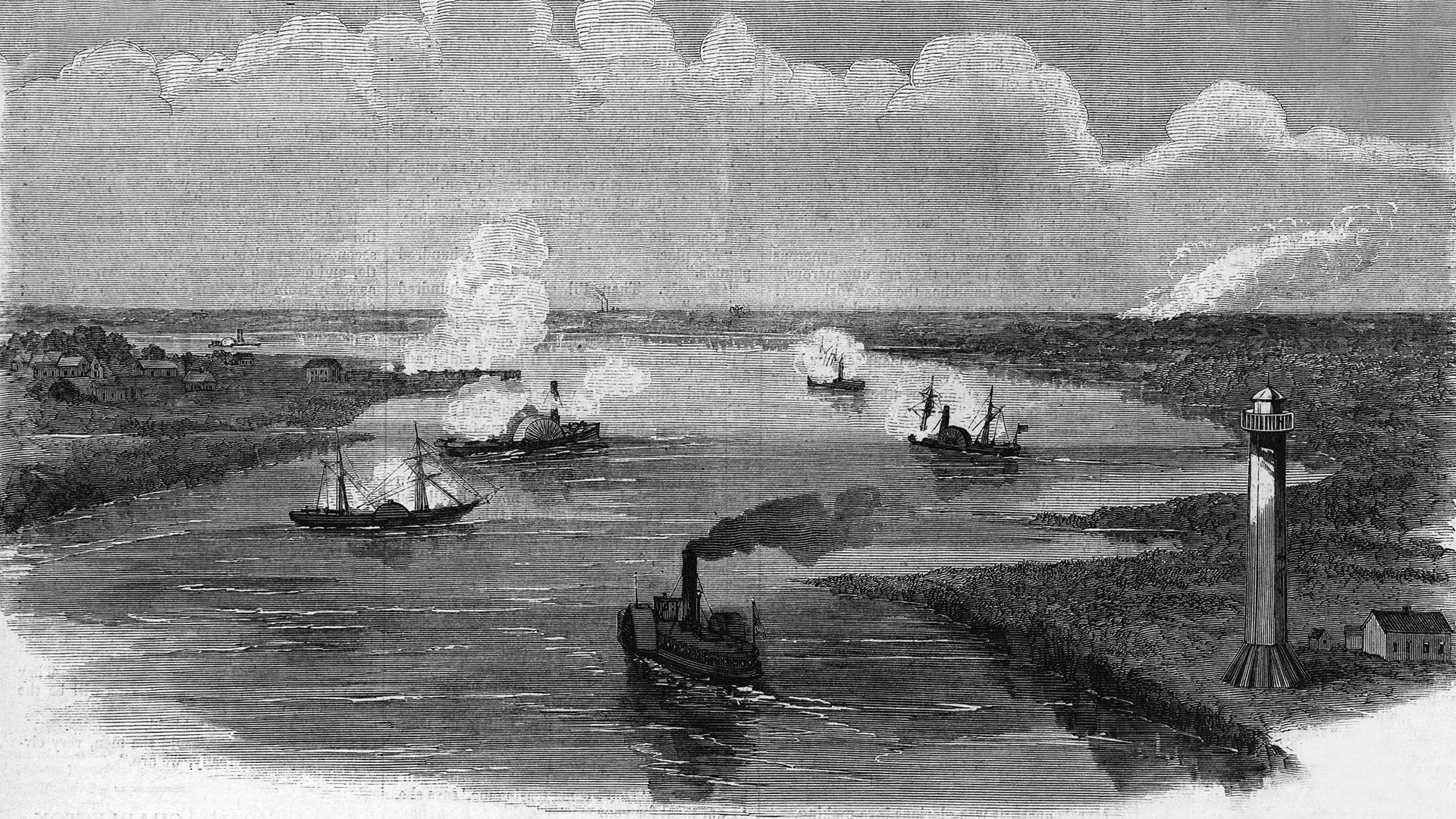

On December 3, another cabinet meeting was held after it was revealed that United States agents had been buying up Britain’s entire saltpeter reserves, most of it due to be shipped. An immediate export ban was put into effect. The Americans, lacking their own supplies of saltpeter, would be severely restricted in the production of gunpowder by this action. An arms and ammunition ban was also instituted, and the Admiralty issued a worldwide alert to the fleet to prepare for action. The first wave of 11,000 troops for Canada left Southampton.

Charles Francis Adams complained to the State Department that all he knew of the Trent affair was what he found in the pages of the London Times. In three weeks, he said, he had heard nothing from his government, most importantly whether or not Wilkes had acted on official government orders. Adams was kept in the dark. Meanwhile, the mood inside the American legation in London was so tense, said one observer, that it “would have gorged a glutton of gloom.” Adams’ own son Henry stormed, “Good God, what’s got into you all? What in hell do you mean by deserting now the great principles of our fathers; by returning to the vomit of that dog Great Britain? What do you mean by asserting now principles against which every Adams yet has protested and resisted? You’re mad, all of you.”

Seward Schemes of War With Britain

Back in Washington during the first week of December, many were hopeful that Britain would take no action in the wake of the Trent seizures. The arrival of British newspapers on December 13 changed all that, leaving no doubt that Her Majesty’s government would demand reparations and that Wilkes was thought to have acted unlawfully. Secretary of State Seward had openly favored war with Britain as a means of uniting the divided country. He thought the South would drop their brothers’ quarrel and support the nation against the foreign power. Clearly he was mistaken, since one of the South’s main aims was to draw Britain into the conflict on their side, with the hope that France would follow. Lincoln, for his part, had doubted the wisdom of Wilkes’ actions from the start, fearing that “the traitors will prove to be white elephants.” Still new to international affairs, the president was willing to leave the matter in Seward’s hands—for the time being, anyway.

Seward soon found that what he thought he had wanted—war with Great Britain—was not an open-and-shut matter. Seward now saw, as did Lincoln, that what Wilkes had done in stopping Trent and removing the two Confederate diplomats was no different from what the British had done to American ships before the War of 1812. They had to stick to the principle of the rights of neutrality at sea. “One war at a time,” said Lincoln, and Seward agreed. Still, they had no wish to antagonize public opinion and said nothing publicly. In his December 1 message to Congress, Lincoln did not even mention the Trent affair, much to the surprise of the body’s members.

On December 18, just before midnight, an exhausted Captain Conway finally reached Lord Lyons’ house in Washington. At 3 pm the next day Lyons presented himself at Seward’s office and delivered the queen’s letter. Seward asked Lyons what would happen if they refused the stated demands or asked for more discussions. Lyons replied, “My instructions were positive and left me no discretion.” Seward asked for more time; it could not be done in seven days. Lyons agreed to come back in two days, when the clock to war would start ticking. Going home, Lyons doubted that an extension of time would make much difference. He sent a coded telegram to Admiral Milne to make ready to evacuate the legation staff to Canada.

Returning to Seward on Saturday, December 21, Lyons was confronted with another request for two more days. Lyons was not the type to ignore his instructions, but he realized that Seward was in a tight corner. He also knew that a letter from France formally supporting Britain’s position would arrive later that day. A new appointment was set for Monday, but Lyons made it clear that this must be the final meeting on the matter. On December 23, Lyons officially delivered Russell’s letter to Seward at the State Department. There was no immediate reply. Lyons had done all he could to help the Americans by delaying, but now the clock was ticking.

The Official American Reply

Seward got Lincoln to call a cabinet meeting for Christmas Day, at which copies of Russell’s letter were given to the members. It soon became apparent that most were against releasing the Confederate envoys. Massachusetts Senator Charles Sumner spoke up, saying that the release of the prisoners would be political suicide; arbitration was the only possible course. However, even as Sumner was speaking news arrived of the official French support for Britain. The room was stunned. Attorney General Edward Bates pointed out that Sumner’s suggestion would not work. Britain’s navy would crush their own and ruin overseas trade, and the nation would be bankrupt. There was already a run on the banks. The cabinet adjourned in the afternoon, agreeing to reconvene the next day. Lincoln, still clinging to the notion of international arbitration of the crisis, asked Seward to present his arguments on compliance in writing the next day, and he would do the same for the arbitration case.

By the next day, most of the cabinet members had come around to Seward’s view that the United States had little choice but to comply with British demands. Seward had been up all night drafting a 26-page response to Lord Russell in which he clearly laid the blame on Captain Wilkes and his failure to take Trent to a prize court. Seward showed the draft to Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P. Chase, who seconded the idea of releasing the Confederate commissioners.

Sumner was not at the cabinet meeting later that day; he was in the Senate where a late resolution was being debated not to release the Rebel envoys. Meanwhile, Seward outlined his case, then waited for Lincoln to make his for arbitration. But the president said nothing, and the cabinet approved Seward’s proposal. When the others had left, Seward asked Lincoln why he had not made a counterargument. Lincoln replied, “I could not make an argument that would satisfy my own mind.”

Seward’s official reply complied with the basic demands of the Russell letter, stating that Wilkes acted without orders and that the captives would be released. But there would be no formal apology. The envoys were contraband and could rightfully be seized. Wilkes’ error was in not seizing Trent as well and taking it to a neutral port for judgment. In a final gibe at the British, Seward suggested that Wilkes, by impressing passengers from a merchant ship, had merely followed British practice, not American, an echo to the War of 1812. However, said Seward, the United States wanted no advantage gained by an unlawful action and that as far as the nation was concerned the captives were relatively unimportant. He concluded, “The four persons in question are now held in military custody at Fort Warren, in the State of Massachusetts. They will be cheerfully liberated. Your lordship will please indicate a time and place for receiving them.”

A Sigh of Relief Across the Pond

In England, the American response was awaited eagerly and with some trepidation. On January 8 news reached London and spread rapidly across the city. In West End theaters, Benjamin Moran wrote, “Audiences arose like one and cheered tremendously.” The press conveyed the general sense of relief. On January 8, the Times commented: “We draw a long breath, and are thankful we have come out of this trial with our honour saved and no blood spilt.” As for Mason and Slidell, the Times judged them “about the most worthless booty it would be possible to extract from the jaws of the American lion.”

Palmerston wrote to the queen, gleefully reporting the “humiliation” of the United States. The queen took a more measured view. Her speech at the opening of Parliament on February 6, 1862, officially closed the Trent affair. “The Question has been satisfactorily resolved,” she announced. “The friendly relations between Her Majesty and the President of the United States have therefore remained unimpaired.”

Mason and Slidell were duly removed from Fort Warren and put aboard the HMS Rinaldo at Provincetown, Massachusetts, and transported to St. Thomas in the Caribbean. On January 14, the diplomats boarded the British mail steamer La Plata for the final leg of their long and torturous journey. When the Confederate envoys arrived in Southampton early in February, it was barely reported in the British press. The nation, like the queen, was still wrapped in mourning for the late Prince Albert. Victoria refused even to receive the visitors. Lord Russell told Lord Lyons, “What a fuss we have had about these two men.” The soldiers Britain had sent to Canada at great expense remained there for some time. They got bored with little to do; some even deserted to America and joined the Union Army.

The South gained little from the Trent affair. Late in February the British government issued a report that acknowledged the effectiveness of the Union blockade. After it was debated in the House of Lords on March 10, Mason sent one of his first dispatches to Richmond. It was gloomy. The blockade was effective, and “no step will be taken by this government to interfere with it.” With her honor defended (and a cheap alternative to Southern cotton located in India), Great Britain could afford to remain on the sidelines while the Americans killed each other with increasing avidity. In the end, the inherent good sense of three men—Prince Albert, Lord Lyons, and William H. Seward—had avoided the looming threat of war between the United States and Great Britain and allowed Abraham Lincoln, as he fervently hoped, to fight “one war at a time.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments