Sixty-five years ago, the fortunes of war in the Pacific changed irreversibly for the Japanese. Since 1931, Japan’s army had asserted control over territory on the continent of Asia, brushing aside Chinese resistance, condemnation and political pressure from other nations, and most recently, the Allied military. Further, Japan had gained control over a vast expanse of the Pacific Ocean, creating an outer ring of defenses extending thousands of miles from the home islands.

Japanese aggression and territorial expansion had been justified as a crusade to rid Asia of European and American colonialism. Their slogan “Asia for the Asians” actually meant “Asia for Japan.” Years of conquest led to the creation of the so-called “Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere,” a weak attempt to legitimize Japan’s preeminent position in the region.

As the Japanese government debated the future of relations with the United States, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto warned that the prospect of a protracted war would surely end in defeat for his country. Yamamoto had visited the United States. He had served as a naval liaison officer and even attended Harvard University, studying English and petroleum management. He had seen firsthand the industrial might of America and warned that the only hope Japan had for ultimate victory would be to strike at Pearl Harbor, crippling the U.S. Pacific Fleet, and following that up with a string of rapid victories.

Yamamoto prophesied that in the wake of Pearl Harbor he would run wild in the Pacific for six months. After that, he made no guarantees. That prophecy proved eerily accurate. Following great victories in Burma and the fall of Singapore and Hong Kong, the terrific blow to Allied morale with the sinking of the battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse, the seizure of the Philippines, the capture of thousands of American soldiers on Corregidor, and the Bataan Death March, Yamamoto was poised to seize Port Moresby at the tip of the island of New Guinea. From there, he would threaten Australia.

During the first week of May 1942, however, the Japanese endured their initial setback as the Port Moresby invasion force was obliged to retreat following the Battle of the Coral Sea. A month later, Yamamoto again went on the offensive, this time with Midway Atoll as his objective. The capture of Midway would provide a staging area for a potential invasion of Hawaii, just 1,100 miles to the southwest.

During the first week of June, the complicated Japanese plan of attack unraveled. At Midway, the loss of four aircraft carriers and hundreds of combat aircraft compelled the Japanese to relinquish the initiative. From that time on, the Imperial forces would be fighting a defensive war. Yamamoto’s prediction was accurate almost to the day.

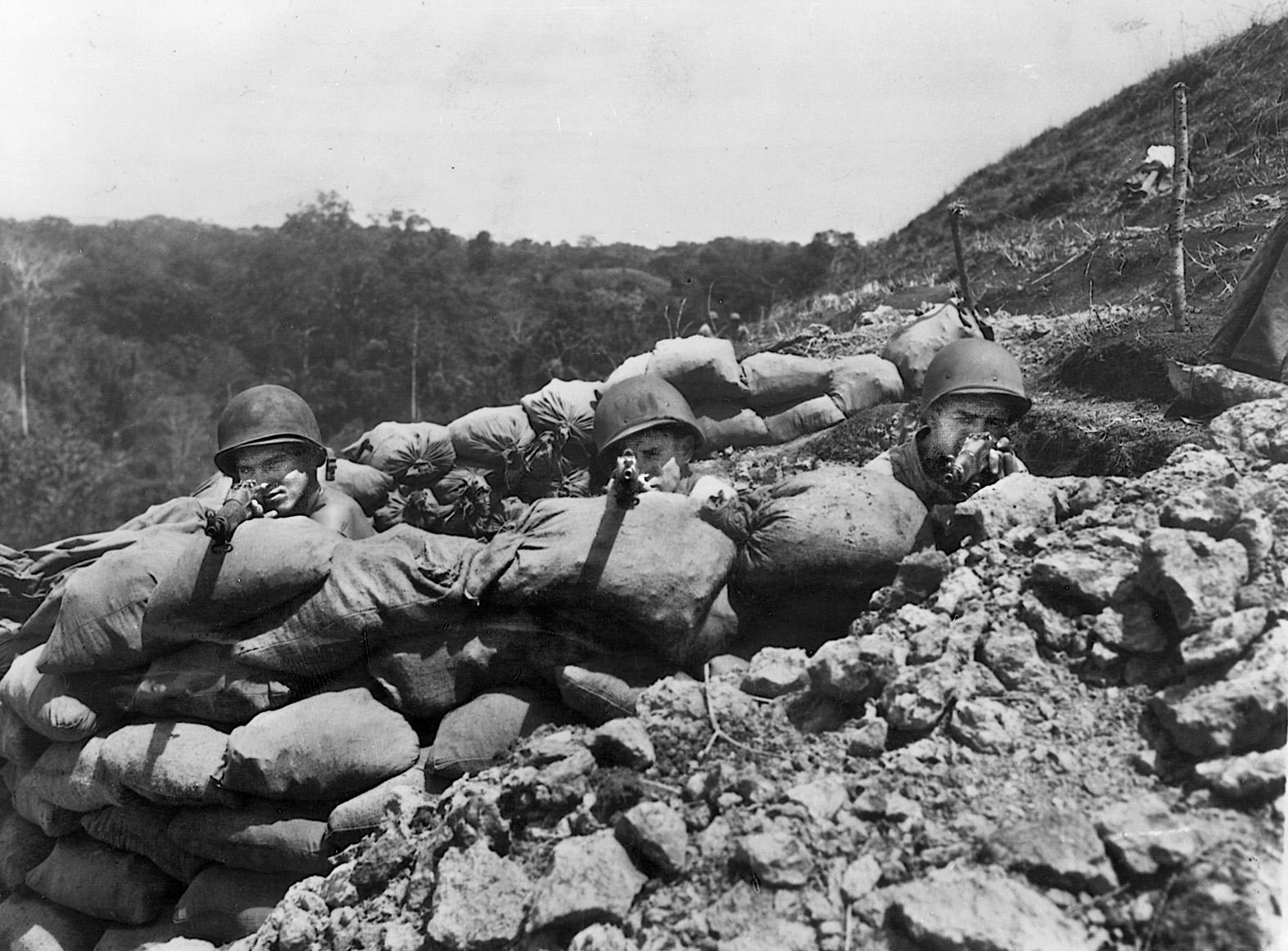

During the first week of August, American troops splashed ashore on the island of Guadalcanal in the Solomons. Their task was to capture the island, particularly its unfinished airfield, from which the Japanese had hoped to provide aircover for operations in the Southwest Pacific. The Guadalcanal campaign was the first offensive land action by U.S. soldiers during the War in the Pacific. The loss of the island after six months of bloody struggle sealed the fate of Japan.

Halted at the Coral Sea, soundly defeated at Midway, and confronted at Guadalcanal, the Japanese were astonished that their timetable of conquest could be upset so thoroughly and so quickly. Yamamoto did not live to see the final defeat of his nation. In April 1943, two months after the loss of Guadalcanal, his bomber was ambushed by a flight of American fighter planes and sent crashing into the jungle on the island of New Britain.

Twelve years of unabated Japanese military triumph came to an end during a period of only 90 days. The island road to Tokyo was long and costly for the Allies; however, from the summer of 1942 forward, the outcome was never in doubt.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments