In July 1942, the United States military stood at a crossroads in the Pacific. Scarcely a month after the great naval victory at Midway, during which four Japanese aircraft carriers were sunk and Japanese expansionist aims in the Central Pacific thwarted, the American land offensive was set to begin. U.S. Marines were training for the invasion of a small island in the Solomons chain known as Guadalcanal.

Although senior American military commanders realized the magnitude of the Midway victory, they remained cautious and well aware that the course of the war remained fraught with peril. Should the land campaign on Guadalcanal that was set for August fail, the Japanese might once again seize the initiative and renew their threat to Australia. The Japanese juggernaut had previously been victorious everywhere in the Pacific Rim, occupying French Indochina, forcing the capitulation of the British bastion at Singapore, seizing Hong Kong and the Dutch East Indies.

The stinging surprise attack on Pearl Harbor that occurred December 7, 1941, had occurred only seven months earlier, and much of the crippled U.S. Pacific Fleet was undergoing repairs or still mired in the muck of the harbor’s shallow waters while salvage operations were in progress. Japanese aircraft had sunk the British battleship HMS Prince of Wales and the battlecruiser HMS Repulse off Malaya on December 10, Wake Island had fallen later in the month, and another debacle befell the Royal Navy at the hands of marauding Japanese carriers in the Indian Ocean.

Then there was the devastating defeat of U.S. forces in the Philippines and the horror of the Death March as more than 75,000 American and Filipino prisoners were forced to march up to 80 miles from the Bataan Peninsula across the island of Luzon. Although the American public was not informed until three years later of the Japanese cruelty that resulted in prisoners dying at a rate of 30 or more per day, there was growing concern among American military and political leaders that these unfortunate captives were being treated brutally.

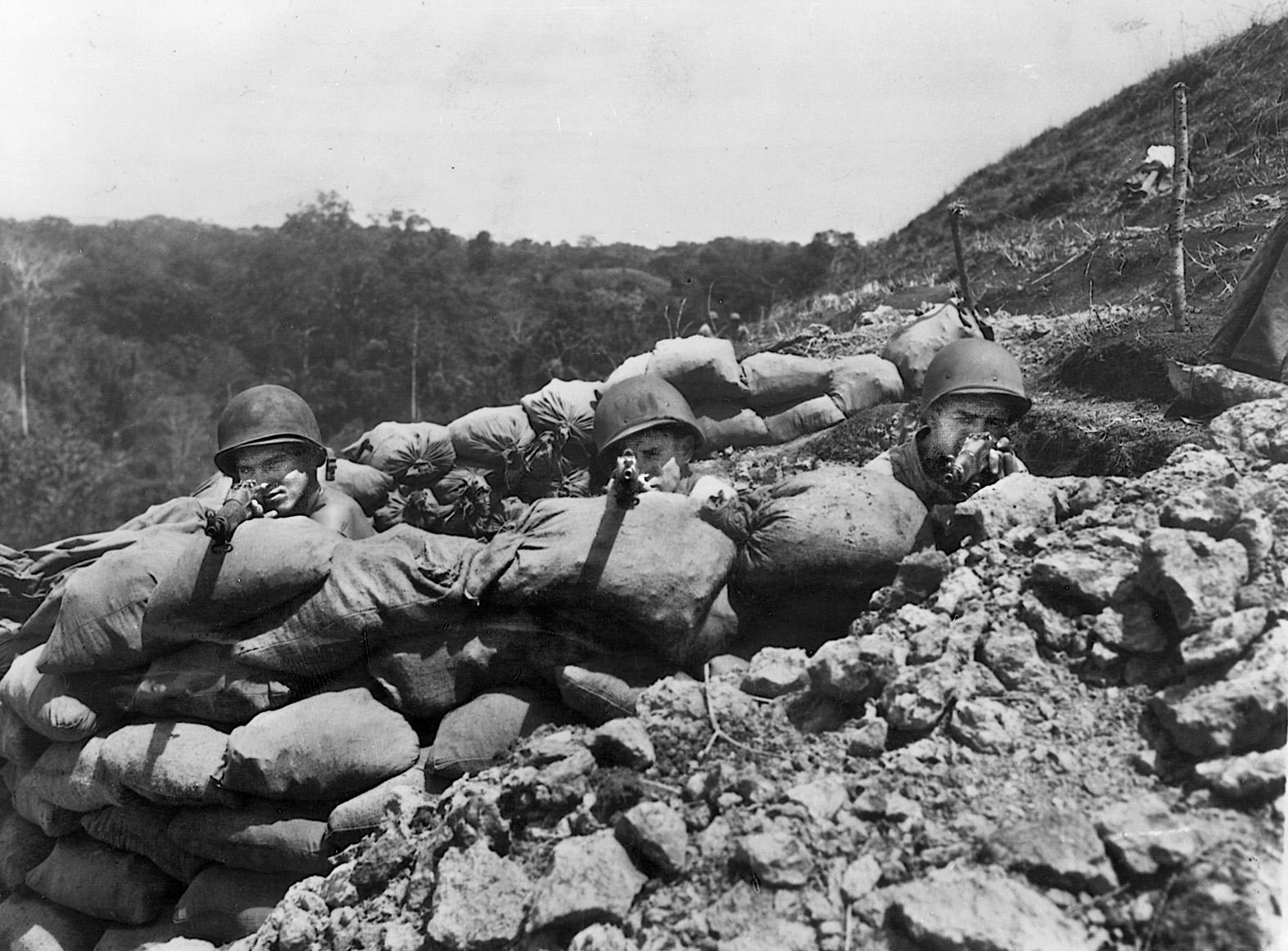

When the U.S. 1st Marine Division landed at Guadalcanal on August 7, the initial calm was deceptive. Months of savage fighting around Henderson Field, along the banks of the Ilu River, and at high ground that aptly came to be known as Bloody Ridge, tested the men of the 1st Marine Division, the 1st Raider, and 1st Parachute Battalion along with the U.S. Army reinforcements landed later. A series of nocturnal naval knife fights took place at close quarters in the waters surrounding Guadalcanal, and the Japanese inflicted serious losses, particularly during the Battle of Savo Island during which four cruisers, USS Vincennes, USS Astoria, USS Quincy, and the Australian HMAS Canberra, were sunk.

On land and sea, the victory at Guadalcanal was a near-run thing. President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston Churchill had agreed previously on a “Europe First” strategy, meaning that the Guadalcanal operation had been conducted on a shoestring. Had the Japanese prevailed, the Allies would still quite likely have won the war. However, the island road to Tokyo would have been a much more arduous trek, consuming even greater quantities of resources and costing innumerable additional lives. When the island was declared secure in February 1943, after seven months of fighting, some Japanese officers themselves acknowledged that the tide had turned inexorably in favor of the United States.

Major General Kiyotake Kawaguchi, commander of the Japanese 35th Infantry Brigade during the struggle for the island, later commented, “Guadalcanal is no longer merely a name of an island in Japanese military history. It is the name of the graveyard of the Japanese army.”

Shortly after the war ended, General Torashiro Kawabe, Deputy Chief of Staff of the Imperial Japanese Army related, “The turning point of the war, I believe, following our series of victories, was at Guadalcanal.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments