By Edward Paraubek

On February 23, 1942, Red Army Day, the People’s Commissar of Defense, Josef Stalin, issued Order No. 55. It read in part as follows: “But the enemy’s efforts have been in vain. The initiative now is in our hands and the futile attempts of Hitler’s out of tune, rusted machine are unable to withstand the pressure of the Red Army. The day is not far when a powerful blow of the Red Army will hurl back the enemy beasts from Leningrad, clear from them the towns and villages of Byelorussia and Ukraine, Lithuania and Latvia, Estonia and Karelia, liberate the Soviet Crimea, and all over the Soviet land the red banners will again soar victoriously.”

At the end of 1941, six months after the Germans launched Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the Soviet Union, the Soviet losses in territory and human lives were staggering, without precedent in modern military history. Some 570,000 square miles, an area equal to that of all occupied Europe, with a population of no less than 70 million and enormous industrial and agricultural output, was lost. For all practical purposes, the original Soviet air force and armor ceased to exist, and of those Red Army men who met the German onslaught in June, only 8 percent were still in the ranks.

Despite these tragic, crushing facts, the mood of the Soviet supreme commander, Premier Josef Stalin, was optimistic because of recent news from different corners of the front. A Soviet counteroffensive, launched on December 5, had driven the Germans from the gates of Moscow and liberated Tula and Moscow provinces. Rostov was retaken, and the railroad town of Tikhvin, the key to the survival of Leningrad, was recaptured after a desperate and furious offensive. Stalin was convinced that all strategic dispositions had changed in favor of the Red Army and that the Moscow offensive would continue unabated, in conjunction with massive strikes along all the length of the enormous front.

When the always cautious and prudent Chief of General Staff Marshal Boris Shaposhnikov timidly suggested consolidating the achieved gains and switching to strategic defense all along the front, Stalin brushed him aside, saying, “Hitler is already exhausted. With a unified blow along all fronts we will overrun his armies and throw them off our land. The Soviet people will not understand us, comrades, if we will call them to passive defense.”

On the last day of December a meeting took place in the Kremlin during which plans for the next year’s campaign were outlined. At the beginning of January, these plans were submitted for Stalin’s approval. The final product became known as the Soviet Supreme Command or Stavka’s directive letter. On January 5, Stalin personally dictated the final paragraph: “Our task is not to give the Germans breathing space but drive them westward without stopping, forcing them to spend their reserves before spring, when we will have new great reserves, and the Germans will have no reserves, thus providing the complete destruction of the Hitlerite forces in 1942.”

It was a rather cumbersome piece of literary work, but its military implications would prove outright deadly for the Soviets.

According to this plan, a few major strategic operations were to be conducted in which nine out of 10 Soviet Fronts, or army groups, including a newly created Crimean Front, were destined to take part. In the south an immediate campaign to liberate the Crimea and the besieged city of Sevastopol would begin. The Southwestern Front was to retake Kharkov and secure Donbass, with its rich coal deposits. In the west, the offensive toward Smolensk and Byelorussia was to continue.

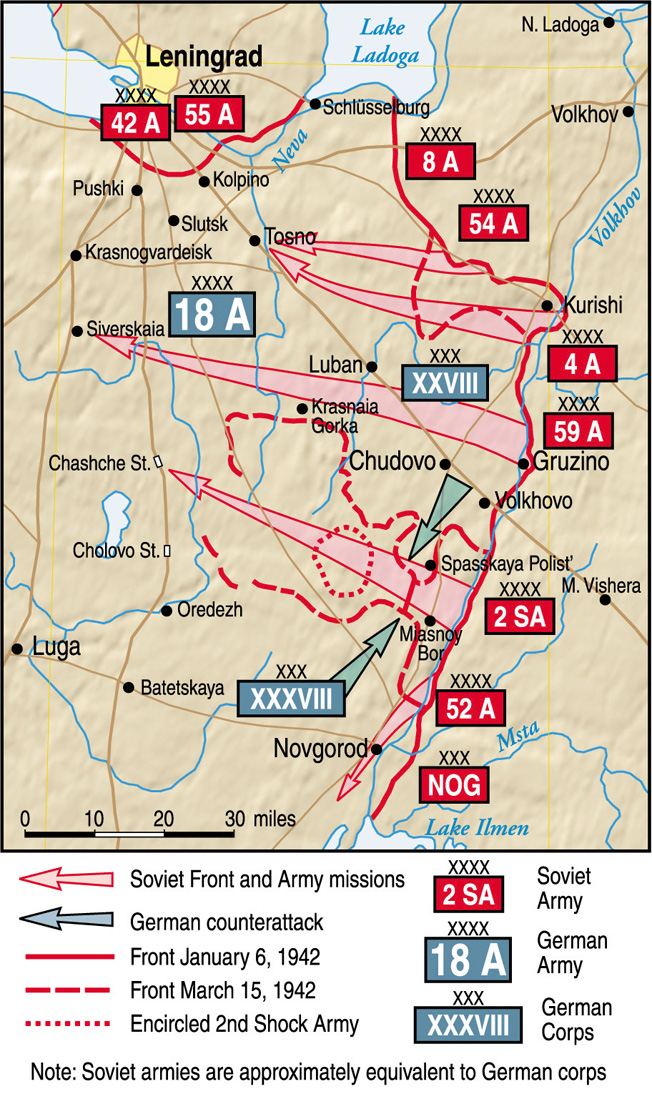

In the north, the combined efforts of the Leningrad Front and the recently created Volkhov Front would break through the German 18th Army defense line. The armies of the Volkhov Front, advancing in a northwesterly direction, would meet the troops of the Leningrad Front driving south, thus shattering the German ring around Leningrad. The enemy units in the area of Chudovo-Luban would be isolated and destroyed.

The situation in Leningrad, the second largest city of the Soviet Union and one of its most important industrial centers, was catastrophic. The city had been under siege since September 8, 1941, when German troops captured the town of Shlisselburg, where the Neva River exits Lake Ladoga, and severed all land communications with the rest of the country. In the west, Finnish troops reached the pre-Winter War border on the Karelian Isthmus and took up a defensive position there. In the north, they stopped at the Svir River in the Ladoga-Onega gap. The Germans cut off the city from the south, effectively blockading it.

When Told of These Details, Stalin Simply Shrugged and Said, “This is War. People are Dying Everywhere.”

Since the end of November, the city had been supplied by auto road across the frozen surface of Lake Ladoga. The volume of delivered supplies was not even close to providing enough food for the fighting armies of the Leningrad Front and the remaining civilian population, which was still more than two million. People had begun dying from famine by the end of October. By the beginning of November, there were no dogs or cats left in the city. In December, the famine was exacerbated by the unusually low temperatures, pushing the death toll to 55,000. In January this climbed to 95,000. No less deadly, February was ready to follow.

Stalin was informed about the conditions in the city. It is difficult to surmise what his real feelings were when he learned details about life in the frozen and dying city, about massive death from starvation, frozen corpses on the streets, cases of cannibalism. Allegedly for the safety of this city, he had started the war with Finland only two years earlier. When told of these details, he simply shrugged and said, “This is war. People are dying everywhere.”

The strategic goals of the planned operation were very ambitious. The 4th Army of the Volkhov Front and the 54th Army of the Leningrad Front were ordered to break through the German defenses along the Volkhov River and advance in the direction of Tosno, a town on the Leningrad-Moscow railroad, capture it, and link with the advancing 55th Army of the Leningrad Front. This would isolate and eventually destroy the German forces in the Mga-Shlisselburg corridor.

The 59th Army and the 2nd Shock Army, representing the main striking force of the coming operation, received the mission to attack northwest toward the Siverskiy station on the Luga-Leningrad railroad, conducting a deep envelopment of Leningrad from the south. A combined effort with the 4th Army would cut off the German XXVIII Corps in the Chudovo-Luban area. The 52nd Army was ordered to strike south, capture Novgorod, and link up with the forces of the Northwestern Front.

The Soviet High Command expected that the result of this operation would be not only the end of the siege of Leningrad, but also the destruction of German Army Group North and the liberation of the Baltic republics. At the end of 1941, the Red Army was about to bite off more than it could chew.

Lieutenant General Mikhail Khozin was appointed to command the Leningrad Front. Commanding the newly created Volkhov Front was Army General Kirill Meretskov, former chief of the general staff of the Red Army. He had only recently been the object of torture and humiliation in the cellars of the notorious Lubianka Prison in Moscow. The new Front received four armies, the recently formed 52nd and 4th, already blooded in the stubborn battle for Tikhvin, and two fresh armies from the Reserves of Stavka, 2nd Shock and 59th Regular.

The influx of men and equipment gave the Volkhov Front and the left flank of the Leningrad Front numerical and technical superiority over their opponents in men, artillery, and aircraft. In the sector of the 2nd Shock Army, this advantage was an overwhelming five to one in men and three to one in tanks. However, a catastrophic shortage of ammunition, especially for artillery, seriously diminished these advantages.

The terrain where the attack was planned was extremely unsuitable for military operations. It was a thickly wooded, roadless area with impassable marshes and numerous though relatively small rivers and streams, with the sole exception of the 450-yard-wide Volkhov River. This forbidding terrain prohibited the use of armor; even infantry would be hard pressed to advance and keep its lines of supply and communications functioning.

What were the Soviet High Command considerations for embarking on a strategic offensive on such difficult terrain? First, in the middle of a severe winter most marshes and all rivers were frozen solid and could provide enough support for armor and supply columns to move. It imposed, of course, rigid time restrictions on the operational schedule. The goals had to be successfully achieved before the spring thaw set in.

The Soviet High Command, encouraged by recent success in fighting under winter conditions, believed that snow, cold temperatures, and difficult terrain would be allies of the Red Army. They based this assessment first on the fighting around Moscow, where the Germans proved to be completely unprepared for winter warfare. Second, the recapture of Tikhvin and a successful Moscow offensive reminded the political leadership of the old adage, “The summer was yours but the winter will be ours.” Stalin, euphoric with high expectations, could not see what field commanders and the leadership of the general staff already realized—that the Moscow offensive was quickly running out of steam.

The Luban offensive was scheduled to start at the end of December, but harsh winter weather impeded the concentration of troops and supplies. Stavka was forced to postpone the operation until January 6. Even this extra week could not remedy the numerous problems, but this time Stalin was adamant and refused any further delays. He ordered four armies to start their attack on January 6, without waiting for the 2nd Shock Army to get ready.

Despite its numerical superiority, the Volkhov Front was clearly unable to mount a successful offensive. It was short of ammunition, fuel, and food. Its attacking troops were not properly concentrated. Its rear and reserve units were not in position to efficiently support advancing front-line troops. To add to the list of problems, the Germans were fully aware of the coming attack and were well prepared to meet it.

After four days of continuous bloody attacks, the Soviet troops gained no ground and suffered heavy losses. The attack was called off on January 10. The troops received a few days of respite to prepare for a new assault. The simultaneous attack, this time by all five Soviet armies, was resumed on January 13.

After a few days of heavy fighting, the 2nd Shock Army under its new commander, Lt. Gen. Nikolay Klykov, finally succeeded on January 17 in crossing the Volkhov under enemy fire and penetrating the German defensive line, pushing aside the enemy’s 215th and 126th Infantry Divisions. After two more days of bitter fighting, the 2nd Shock Army broke through and captured the station and settlement of Miasnoy Bor on the Novgorod-Chudovo railroad. This promising news was immediately reported to Moscow. The response was not long in coming: “When the 2nd Shock Army consolidates this success, commit to the battle the 13th Cavalry Corps of General Gusev. I rely on you, comrade Meretskov. Stalin.” A cavalry corps consisting of three divisions, supported by the 111th Infantry Division, was thrown into the breach early in the morning of January 24. In five days, while brushing aside light covering detachments of the enemy, this force managed to advance 30 miles to the northwest. Its task was to reach the Moscow-Leningrad railroad between the Luban and Chudovo stations, thus cutting off the main supply line of the German XXVIII Corps.

In the beginning of the offensive, the 2nd Shock Army concentrated its forces and delivered a blow on a relatively narrow 15-mile front. Unsupported by either the 52nd or 59th Army on its flanks, the 2nd Shock Army was eventually forced to widen the front of its advance. Originally ordered to head west-northwest with the goal of cutting off the Luga-Leningrad railroad and blocking the retreat of the German 18th Army, the 2nd Shock Army was forced to advance northeast toward Luban and meet the 54th Army of the Leningrad Front, thus encircling the XXVIII Corps in the Luban-Chudovo area. Moreover, the army’s failure to widen and secure the six-mile gap between the villages of Spasskaya Polist’ and Lubtsy, the umbilical cord through which all supplies and communications of the army were flowing, was to haunt the advancing army and eventually seal its fate.

The attempt of the Leningrad Front’s 55th Army to break the German encirclement from inside was repulsed. Though starved and exhausted, the army managed to tie down the German forces, thus preventing them from reinforcing the troops facing the attack of the 2nd Shock Army in the south.

There Were Fully Clothed Corpses All Around, but it was Impossible to Remove the Boots From Frozen Bodies.

The 54th Army of the Leningrad Front was originally aimed west toward Tosno on the Leningrad-Moscow railroad. After one and a half months of unsuccessful and bloody attempts to break through, Stalin expressed dissatisfaction with its commander, Maj. Gen. Ivan Feduninsky. Stavka ordered the army reorganized. The operational direction was changed, and the army was ordered to strike southwest no later than March 1 to exploit the success of the 2nd Shock Army and join it at Luban no later than March 5. All these Stavka orders turned out to be too optimistic.

The 54th Army managed to start the new assault on February 28, but it achieved meager results after several days of heavy fighting against well entrenched Germans. Regrouped and reinforced, the army resumed its offensive on March 5, again unsuccessfully. Only on March 15, after five days of bitter fighting, did it finally manage to penetrate the German defenses and advance 14 miles to Luban. There were only 10 miles left between Soviet front-line units and Luban, but covering these 10 miles was beyond the army’s capacity. The road to Luban turned out to be two years long.

In March, the 2nd Shock Army continued its advance northwest toward the Leningrad-Novgorod railroad, which it managed to sever, and northeast toward Luban and the Leningrad-Moscow railroad. Originally planned as a blow by a tightly clenched fist, the operation turned into a two-fingered poke. In mid-March, the 80th Cavalry Division of the 13th Cavalry Corps broke through enemy defenses near the village of Krasnaya Gorka, less than 10 miles from its objective. It appeared that one more desperate effort would tip the balance, cutting off the XXVIII Corps. A couple of days later, German infantry and artillery hurled the Soviets back from Krasnaya Gorka. Still, some considered this only a local setback. It could possibly be reversed by a renewed effort from the 2nd Shock Army.

Then, the weather turned brutally cold. The winter of 1941-1942 was unusually severe, with temperatures dropping to -35 degrees Fahrenheit on a daily basis. Tired and half frozen men would frequently fall asleep around campfires. Heavily padded jackets and pants would catch fire like powder, often causing serious or even life-threatening burns. The most vulnerable of the soldiers’ winter clothing was their felt boots. When burned through, they would become useless, forcing the soldiers to look for new ones. There were fully clothed corpses all around, but it was impossible to remove the boots from frozen bodies. There were reports of some soldiers obtaining axes and hacking off the booted legs of the dead. Others reportedly broke off a leg at the knee and then dragged the limb to the campfire, warming it sufficiently to remove the coveted item.

The terrible cold thickened the ice on rivers and streams to five feet or more, enough to support not only wheeled transport but also armor. Despite such cold, some marshes were left unfrozen, and many trucks, artillery pieces, and men sank to their deaths, betrayed by treacherous snow cover, which was hiding the danger. From the beginning, the Soviet command knew about the terrain and was racing against time. At the end of March it became clear that spring had arrived ahead of Soviet military success.

Another factor intervened on March 19. The six-mile-wide corridor at Miasnoy Bor was the only passage connecting the advancing army with its supply base. It was the most vulnerable place in the whole disposition of the 2nd Shock Army; entrenched German units on both sides of the corridor were poised like two daggers aimed at a jugular vein. It had never been easy for reinforcements and supply columns to cross this narrow valley of death under the enemy’s artillery fire. However, columns were going in both directions, into the cauldron with ammunition, food, and medicine, and out of it with wounded and sick. On March 19, this flow stopped; the Germans closed the corridor. The implications were felt immediately. The 2nd Shock Army had already been short of ammunition. During the advance the army was not able to build up adequate depots, and as soon as the flow of supplies stopped the shortage was immediately and painfully felt. The main casualty of this interruption was food, which on the list of priorities was allocated to the second or even third position, after ammunition and medical supplies. Hunger became part of daily life.

It took the Russians two weeks of fierce fighting to restore the corridor, but the situation improved only marginally. The restored supply line was substantially narrower, and German artillery was able to completely shut down the flow of supplies during daytime. The April thaw finally arrived, and frozen roadways became seas of impassable mud, pockmarked with shell craters. The response to this new, though expected problem, was to build corduroy roads. Thankfully, there were abundant trees for these tasks. The work itself was backbreaking and time consuming. Units were mobilized to cut down the trees, drag them through the melting snow and mud, and put them into place.

In March the first cases of scurvy and night blindness appeared, unmistakable signs of malnutrition. In the middle of the month, when these cases were growing at an alarming rate, the decision was made to employ a remedy used in gulag camps and in besieged Leningrad. This involved drinking a concoction of fir tree needles steeped in hot water. It was an effective, yet repulsive and bitter, liquid.

By the end of March, it became clear that the Soviet troops had lost their race against time. Rations were reduced to a nonsustainable level, a few ounces of crumbs daily, occasionally accompanied by flour or oats. Men were reduced to scavenging. The horses, which had fallen during winter, their bodies now exposed by the melting snow, were consumed. The worst was yet to come.

In desperation, the Soviet command turned to resupplying the troops by air. For this purpose they used the old workhorse of the air force, the light bomber and transport U-2 (since 1944 known as PO-2), which it was said could land on a five kopeck coin. It was a two-seat, single-bay light biplane used mostly for night missions, taking full advantage of the long winter nights in these latitudes. Because of its low speed, only 105 miles per hour, it was completely defenseless against German fighters. The number of available planes was very limited, a few dozen at best, with a maximum load capacity of only 550 pounds, or roughly five to six sacks of flour, 12 to 15 with dry bread, or 10 to 12 boxes of canned goods. They were flown by young lieutenants, who, to avoid attacks by marauding German fighters, were flying at tree- top level over the forest and even below that along the river valleys and marshes. In turn, it made them very vulnerable to ground fire, but it was the price of their deadly game. At the end of April, the Northern Lights took away their advantage of nocturnal cover.

It was impossible to feed an army of 80,000 men with occasional deliveries of a few dozen sacks of flour, but those brave pilots continued their suicidal, hopeless work. Those young lieutenants often died before accomplishing their fifth mission.

One day an American-built Douglas transport arrived. The pilot steeply banked his plane to the left, locked it into a circling pattern, and started passing over a clearing in the woods, dumping sacks of dried bread. A German fighter came out of nowhere, and its machine-guns set the transport’s right engine ablaze. “Jump, jump!” yelled the people on the ground, as though the crew could hear them. But they did not want to jump. They continued their doomed flight, trailing black smoke, dumping and dumping the sacks. The German fighter repeated its attack. The Douglas shuddered, wrapped itself in a black cloud of smoke, and went down.

Each pound of food in those planes was worth its weight in gold, and every hour of flight was a hide-and-seek game with death. Yet, the political leadership saw fit to displace a portion of the food cargo with propaganda leaflets exhorting the starved soldiers to fight heroically for the Bolshevist cause and for Stalin. These pieces of paper could not even be used to roll a cigarette. There was no tobacco anyway.

On January 18, Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb, commander of German Army Group North, was dismissed from his position because of poor health and replaced by Colonel General Georg von Kuechler, the 18th Army commander. The health issue was, of course, a convenient excuse. In fact, the field marshal had persisted in his demand to withdraw the army group westward to a more defensible position. Leeb’s dismissal was the last in a chain of a major reshufflings at the top of the German High Command due to setbacks, which began with the fall of Rostov in November 1941.

The 2nd Shock Army was Doomed. The Only Issue now was the Extent of the Catastrophe.

Now, in April, it was Stalin’s turn to rearrange his commanders. On April 16, the 2nd Shock Army commander, Lt. Gen. Nikolai Klykov, who had fallen seriously ill, was flown out of the cauldron to a hospital. He was replaced by the recently appointed deputy commander of the Volkhov Front, Lt. Gen. Andrey Vlasov, a hero of the defensive battles in the Ukraine in the summer of 1941 and a victorious commander of the 20th Army during the fighting around Moscow.

On April 20, the new commander of the 2nd Shock Army arrived in the pocket. On April 23, a dumbfounded General Kirill Meretskov read a new directive from Stavka saying that the Volkhov Front had been abolished and its armies incorporated into the Leningrad Front under Lt. Gen. M.S. Khozin. Meretskov was ordered to depart for the western front line and to take the 33rd Army under his command. This untimely reorganization was the result of Khozin’s many tireless appeals to Stalin with promises of long-awaited success. Stalin finally relented despite the objections of the Chief of General Staff, Marshall Boris Shaposhnikov.

The presence of Meretskov in Malaya Vishera at the headquarters of the Volkhov Front in April and May would not have changed the strategic outcome of Luban operation; the campaign was lost, and the 2nd Shock Army was doomed. The only issue now was the extent of the catastrophe.

On April 30, the 2nd Shock Army was ordered to stop all offensive operations, switch to strategic defense, and begin the gradual withdrawal of a few selected units toward Miasnoy Bor. The process of withdrawal started immediately and was conducted in an orderly manner under very challenging circumstances. The brave cavalrymen of the 13th Cavalry Corps, who in the middle of March were so close to Luban, were withdrawn, together with a few depleted infantry divisions and one armored brigade.

Stavka issued a new order two weeks later under the signatures of Stalin and Alexander Vasilevsky, deputy chief of the general staff, who replaced the sick Shaposhnikov. The order authorized the 2nd Shock Army to break out of semi-encirclement. The line of the new defensive position for the 2nd Shock Army was designated along the western bank of the Volkhov River in the area of Miasnoy Bor-Spasskaya Polist’. It meant, for all practical purposes, that the 2nd Shock Army must return to the same position it had occupied at the beginning of the operation four months earlier. It was a final admission of the fact that the operation had failed. By May 20, the strength of the 2nd Shock Army had decreased by half.

On May 31, the Germans again closed the corridor—this time permanently. The last act of the 2nd Shock Army tragedy had begun. The army, thoroughly exhausted from incessant combat, lack of food, and exposure to the elements, was in its death throes. The already meager rations were reduced again, this time to 1.5 ounces of bread crumbs per day. In the cauldron, young trees, at first aspens and lindens, then all others, were stripped of their bark. Buds and later fresh leaves disappeared, worms, frogs, and tadpoles became rare delicacies. The army staff reported to the Front headquarters in one of its last radio communications, “Massive mortality from hunger is taking place.”

Incidences of suicide increased among officers and enlisted men. The corpses of dead soldiers were found with pieces of flesh cut from their bodies. Occasional deliveries from death- defying U-2s were not even drops in the bucket. Prevented from landing, they had to resort to dropping canned goods or sacks with dried bread. Those cans that managed to land on solid ground were were sometimes the cause of fights among the soldiers. Those who succumbed to temptation and hid or ate food instead of surrendering it to their commanders were all shot.

Besides the absence of food, ammunition, and medicine, there was a lack of water. It was everywhere, in trenches, shell craters, inside the tents, in men’s boots, but there was none to drink, nothing with which to wash already used bandages, nothing to sterilize surgeons’ instruments. Even snow, the seasonal water provider, melted and turned into undrinkable water. In desperation, a method was developed to obtain drinking water that would horrify any reasonable man. Large wooden boxes without bottoms were built. They were wrapped in layers of medical gauze and lowered into holes dug in water-logged soil. In several hours, these improvised wells were full of dark brown water. It was picked up by buckets, filtered through multilayered gauze again, and distributed to medical stations, the wounded, and units in the field. The ration was one cup per day per man.

On June 8, the Volkhov Front was reestablished. After Khozin was removed and sent to a command in the western area, he never managed to rise again to the position of Front commander. In March 1944, he was sent from the fighting army to command a secondary military district in the rear. In his place, Lt. Gen. Leonid Govorov, the valiant commander of the 5th Army during the fighting around Moscow, was appointed as commander of the Leningrad Front.

General Meretskov came back to his resurrected Front with the specific task of saving the 2nd Shock Army. Meretskov was a good commander, but he was not a magician, and the task of extricating the 2nd Shock Army would have required a miracle. This miracle would have to be accomplished without any additional forces; Stavka had nothing left in reserve.

At the end of May, two major Soviet offensives in the south, near Kharkov and in the Crimea, failed. A total of 240,000 troops of the Southwestern Front and 150,000 of the Crimean Front were facing annihilation. Besieged Sevastopol was doomed. The offensive of the Western and Kalinin Fronts in the Rzhev-Viasma area had come to a screeching halt, at the cost of 270,000 dead. In light of these catastrophes, the destruction of the 2nd Shock Army was a relatively minor setback. Since it had become clear in mid-March that the ambitious goals of the Luban operation were unrealistic, Stalin had begun losing interest in it.

As soon as hopes of lifting Leningrad’s blockade and defeating German Army Group North were dashed, there was not much left to attract Stalin’s attention to this theater of operations. After all, just the capture of Luban, a name hardly known to anybody, rang hollow. Later, simply overwhelmed by the magnitude of the Red Army’s multiplying disasters, Stalin switched his attention to other sectors.

Only one thing related to this area still attracted his attention: the fate of the 2nd Shock Army commander, General Vlasov. Stalin ordered special army groups and partisan detachments to conduct searches for him. The reason for Stalin’s level of interest in Vlasov is unknown. The fact remains that he wanted him back. From the end of June until the middle of July, when the Germans announced Vlasov’s capture, Stalin asked daily about the progress in the search for him.

In the middle of June, the Soviets, retreating to the southeast while engaged in heavy fighting, were squeezed out of their Olkhovka-Finev Lug defensive line. An attempt to stop the German advance along the Novgorod-Leningrad railroad at Glukhaya Kerest also failed. The distance from this abandoned line of defense to Miasnoy Bor in the center of the now-closed corridor was 16 miles. The 2nd Shock Army, finding itself inside the tightening ring, continued its retreat toward Miasnoy Bor. The Germans regrouped their forces and organized a defense line along the eastern bank of the Polist’ river. The Soviets were stopped cold.

The Casualty Rate was 95 Percent. Among Them Were 50,000 POWs.

The desperate Soviets had to abandon the only available landing strip, near the village of Novaya Kerest’. The corduroy roads were clogged with trucks, prime movers with artillery pieces in tow, and buses carrying wounded. Soviet artillerymen received orders to destroy the immobilized columns to prevent equipment from falling into the enemy’s hands. They fired through open sights. Many of those trucks and buses are still there today, 60 years later.

On June 24, the staff of the 2nd Shock Army received its last radiogram from the Stavka, an order to filter through the enemy lines by dispersing into small, separate groups. By this time the army had ceased to function as a unified body. The army had been abandoned: there would be no help.

Some groups tried to break through the German lines in the south, literally walking on corpses. Only a few managed to reach Soviet lines. More than 10,000 wounded were left behind in the meadow between the Glushitsa and Kerest’ Rivers, appropriately named “Valley of Death.” A few groups attempted to move north, hoping that the Germans would not expect them to move deeper into the German rear. The Germans set ambushes along the Kerest’ River, where a great number of the Red Army soldiers perished or were taken prisoner.

The group that included General Vlasov moved away from the slaughterhouse along the Polist’ River. They managed to avoid German patrols and cross the Kerest’. After a few days of wandering in the woods, the group split up on June 25. Vlasov, accompanied by a few men, moved northwest. On July 12, Vlasov was arrested by pro-German local police in the village of Tukhovezhi, 30 miles northwest of the city of Novgorod. He was handed over to the German XXXVIII Corps. The following day, he was delivered by truck to 18th Army headquarters at the Siverskiy railroad station.

Individual stragglers from the 2nd Army continued appearing at the front-line positions of the Soviet armies of the Volkhov and even Northwestern Fronts until the end of August. The fate of most of them was not enviable. They were brutally interrogated by Special departments of the NKVD, the predecessor of the KGB, the dreaded Soviet secret police. Many of them landed in the gulags or in deadly penal companies.

The once 85,000-strong 2nd Shock Army ceased to exist, melting into the mass graves, bottomless marshes, and prison camps, or left unburied in the woods to the west of the Volkhov River. Almost 70,000 men were lost. The cumulative casualties of the Luban operation were staggering. During the offensive from January 7 to April 30, a total force of 325,700 comprising four armies of the Volkhov Front and the 54th Army of the Leningrad Front lost 308,367 soldiers. The casualty rate was 95 percent. Among them were 50,000 POWs.

On June 29, Stalin instructed the Soviet Information Bureau to broadcast the following communiqué: “The Fascist scribes are quoting astronomical figures of 30,000 supposed prisoners of war and saying that even more than this were killed. Needless to say, this is a typical Fascist lie. According to incomplete figures, at least 30,000 Germans were killed alone … Parts of the 2nd Shock Army withdrew to a prepared position. We lost 10,000 killed and about 10,000 missing …”

The remains of some of the dead Red Army soldiers still turn up 60 years later in the marshy woods, startling occasional hikers and mushroom hunters. After his capture, General Vlasov collaborated with the Germans. This betrayal cast a dark shadow over the memory of his vanished army for years to come.

Edward Paraubek was born in the Soviet Union and served in the Red Army with the rank of senior lieutenant. He emigrated to the United States in 1978 and resides in Stoughton, Massachusetts.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments