By Jonas L. Goldstein

When Louis XIV assumed the throne of France in 1661, Europe was at peace. He acknowledged as much in his memoirs: “Everything was quiet everywhere. Peace was established with my neighbors probably for as long a time as I should myself desire.” The desire for peace, however, soon conflicted with the new king’s desire for extensive territorial expansion. This lust for territory increased dramatically when Louis married his Spanish cousin, Marie-Therese, in 1660. He now considered the strategically located Spanish Netherlands (present-day Belgium) as part of his rightful dowry. Control of the disputed territory would extend French holdings all the way to the banks of the Rhine, which Louis recognized as one of France’s “natural boundaries.”

The War of the Grand Alliance Begins

Other European nations, beginning with the Spanish Netherlands’ nearest neighbors, the Dutch, naturally disagreed. They were joined in opposition to France by the Protestant princes of Germany, the Holy Roman Empire of central Europe, Sweden, and Spain. For a quarter of a century, fighting flared and sputtered between the French and the Dutch, with Germany, Sweden, and England occasionally drawn into the fray. In 1686, the Grand Alliance took shape against Louis’s territorial ambition, the League of Augsburg, spearheaded by Dutch Statholder William of Orange. England and Savoy were added to the list of nations contesting France. For the next nine years, the War of the Grand Alliance flared and sputtered on land and at sea, spreading as far as North America, where it was known as King William’s War. (Adding to Louis’s woes, the Glorious Revolution of 1688 brought William of Orange to the English throne as William III.) Louis, thwarted for the time being, accepted renewed proposals for peace. While the Treaty of Ryswick ended the War of the Grand Alliance, it did nothing to allay the underlying tensions within Europe that Louis had fanned so recklessly.

As long as Louis was on the throne, France would be a looming threat to the status quo in Europe and the colonies. Another alliance against Louis was formed, consisting of the Habsburg Empire, England, the Netherlands, Brandenburg-Prussia, and most of the other German states. Louis, in turn, was supported by Savoy, Mantua, Cologne, Bavaria, and Spain. The struggle, known as the War of the Spanish Succession, had long been foreseen. The two main competitors for the Spanish inheritance were the king of France and the emperor of Austria, each of whom had married a sister of King Charles II of Spain, and each of whom hoped to place a younger member of his own family on the throne after the king’s death.

Previously, Louis had compromised regarding the Spanish succession by signing two treaties with England that agreed to partition the enormous Spanish empire to preserve the balance of power in Europe. Spanish noblemen understandably objected to this intrusive division of spoils, and the dying King Charles II attempted to settle the issue by leaving his entire empire to Louis XIV’s grandson, Philip, Duke of Anjou. This put the French king in a difficult moral position. Should he accept the provisions of Charles’s will or stand by the conditions of his treaties with the British? He decided to embrace the former and fulsomely recognized his grandson as King Philip V of Spain.

William III of England at first acquiesced, for he had had enough of war. But when Louis, sensing victory, boldly recognized the Catholic pretender Charles Stuart as the legitimate heir to the throne of England, Parliament and the English public cried out for war. This enabled William to win parliamentary support for raising the armies needed to confront France. With Philip as king of Spain, Louis marched his troops into the Spanish Netherlands and thereby provoked the

Habsburg Empire into war.

The Generals of the Alliance

While the allied forces possessed two of the great generals in history in the Duke of Marlborough and Prince Eugene of Savoy, Louis’s army was superior in numbers. Marlborough, born John Churchill, was the eldest son of Sir Winston Churchill and Elizabeth Drake, a descendant of naval hero Sir Francis Drake. At 16, Churchill obtained a commission in the Foot Guards. In 1668, he volunteered to serve with the Tangier garrison and gained valuable experience in irregular warfare fighting against the Moorish tribesmen. Ten years later, he obtained the position of lieutenant colonel in the Duke of York’s regiment. He became a favorite at the court of the sybaritic King Charles II, even sharing one of the king’s mistresses, and after Charles’s death he continued to enjoy the support of his successor, James II.

Turning against James in the Glorious Revolution, Churchill threw his weight behind William of Orange, who rewarded him with the created title Earl of Marlborough and immediately sent him to command the English Hudson’s Bay Company in North America. The abstemious king did not entirely trust the notoriously libertine Marlborough, and he threw him into the Tower of London for a time in 1692 for allegedly conspiring to restore the Catholic monarchy. He was soon freed, but he never again enjoyed the king’s confidence. Luckily for Marlborough, King William fell off his horse and died of a broken collarbone in 1702, bequeathing his kingdom to his sister-in-law, Queen Anne, who had a warmer place in her heart for the gallant, if no longer young, officer. With war now looming again in Europe, the queen appointed Marlborough a Knight of the Garter, a captain-general, and a duke. Through her favor, he became the leader of the confederation of European states now opposing Louis XIV.

The first actions of the War of the Spanish Succession took place in Italy. In 1702, the Habsburg monarch Leopold I sent his best general, Prince Eugene of Savoy, to attack French positions in northern Italy. Eugene, son of the Count of Soissons, had been born in Paris and educated in France. He had married a niece of the powerful French Cardinal Mazarin, but switched loyalties and entered the service of Austria after Louis XIV refused him a command in the French army. Eugene’s early experience was gained in campaigns against the Turks, which led to a command in Italy in 1691. He returned to the east to defeat the Turkish commander Elmas Muhammad at Zenta in 1697.

Eugene’s first objective was to overrun Spanish territories on the Italian peninsula and then strike France’s satellites in Germany. Louis sent an army under the command of Marshal Nicolas Catinat to occupy Rivoli. The French intention was to prevent the Austrian army from entering Italy. However, Eugene was able to outmaneuver Catinat, and Louis was forced to replace him with Francois Villeroi, who in turn was captured in an Austrian raid on Cremona on February 1, 1702, and replaced by the Duc de Vendome. The campaign evolved into one of guerrilla warfare. The French remained in garrisons along an increasingly extended front, never sure where Eugene and his men would strike. The Austrians repeatedly defeated forces that outnumbered them substantially. Louis finally expanded the size of his army in Italy, and in the end Eugene withdrew.

The alliance took further action in July 1702, when the Austrians invaded Alsace with an army under Prince Louis, Margrave of Baden. Meanwhile, an Anglo-Dutch force under the command of Marlborough captured the French fortresses of Venloo, Ruremonde, and Liege along the Meuse River that fall. In the spring of 1703, Marshal Claude de Villars of France advanced through the Black Forest with the intention of attacking Vienna. In the end, he remained in the Danube Valley to hold off the alliance armies of Louis of Baden and General Herman Otto von Limburg-Styrum. Villars maneuvered successfully to keep their armies from joining, and he defeated them at the Battles of Munderkingen on July 31 and Hochstadt on September 31. In the latter battle, the Austrian army dug in between Ulm and Ingolstadt in an effort to block the French-Bavarian thrust along the Danube toward Vienna. Villars routed the Austrians, inflicting 11,000 casualties while losing only 1,000 men. Aggressive French action at the time—which Villars repeatedly urged—probably could have put Austria out of the war. But the timid Maximilian, Elector of Bavaria, refused to join Villars in an all-out drive to take Vienna, and Villars resigned in disgust. Operations on both sides ceased for the year.

Marlborough’s Long March: 5 Weeks, 300 Miles

In the spring of 1704, Louis turned away from the Low Countries. He intended, instead, to conquer the Austrian Habsburgs. His plans envisioned the French commander, Marshal Villeroi, assuming the defensive in Flanders, while armies under Marshal Camille de Tallard advanced across the Rhine. Marshal Ferdinand de Marsin and the Elector of Bavaria would move against the Habsburgs from the Danube, while the French army in Italy would attack through the Tyrol. This, Louis thought, would bring Austria to its knees.

French forces invaded southern Germany in April 1704. Supported by Hungarian rebels, they seemed on the threshold of extinguishing Habsburg power. The fortress cities of Augsburg, Regensburg, and Landau fell to Louis’s forces, and Emperor Leopold I desperately appealed to Queen Anne for immediate assistance. The queen, in turn, looked to her favorite, Marlborough, for advice. Marlborough, who had been contemplating a thrust southward to the Moselle River from the Netherlands, now switched plans and began a bold advance at the head of an Anglo-German army from the Netherlands to the Danube Valley. It was a daring move. Besides taking on the logistical challenges of marching a large army nearly 300 miles in the face of the enemy, Marlborough would unavoidably have to expose his flanks to attack at any time. One false step or aggressive move by the French or Bavarians could throw the entire undertaking into disastrous disarray. To mask his plans from his allies, the Dutch, who understandably opposed leaving their own homeland vulnerable to attack, Marlborough represented his move as a mere thrust toward the Moselle to draw off Bavarian pressure from the United Provinces. He did not say that he had no intention of stopping before he reached the Danube.

The movement was brilliantly organized, with Marlborough arranging for supply depots to be established in advance along the way. In addition, his route was chosen to mislead the French into pursuing him, rather than reinforcing Maximilian. Twenty-one thousand men, 16,000 of whom were English, started the march, crossing the River Maas by a hastily constructed pontoon bridge near Ruremonde on May 20 and rendezvousing at Bedburg, 20 miles northeast of Cologne. Dragoons led the way, riding outside the main stream of infantry and wagons and acting as a protective screen of scouts. Marlborough started the massive march with 34 field pieces and four howitzers. He picked up additional guns along the way. To deceive the enemy, he followed an unorthodox routine. The men were roused at a very early hour, one or two in the morning, and marched at top speed to the next arranged depot. There they drew rations, pitched their tents, and rested during the remainder of the day. By adopting this stop-and-go system, Marlborough hoped to keep his men relatively fresh while also confusing enemy scouts and avoiding the great clouds of dust that normally advertised the presence of great armies on the move.

Each day would begin with long lines of red-coated infantry swinging into the roadway, their bayonet-topped muskets bristling in the breeze. Following the troops was a convoy of wagons laden with ammunition, medical supplies, bricks (to make bread ovens), and tons of oats for the 14,000 cavalry horses, 5,000 artillery horses, and 4,000 draft animals needed by the army. A staggering 100 tons of oats per day was needed to keep the animals in top shape. For the more refined officers, a groaning cortege of baggage carts brought up the rear; they were loaded down with furniture, silver plate, and candlesticks—all the accoutrements necessary to keep a gentleman-officer in suitable trim during the campaign. For the more humble foot soldiers, Marlborough arranged for German cobblers at Heidelberg to prepare enough new shoes for 14 full battalions. In contrast with the haughty French, who simply foraged or stole whatever they needed from the local populace, Marlborough made sure that the cobblers were well paid for their services.

Even with such meticulous advance planning, the grueling effort soon took a toll, and large numbers of infantrymen dropped out from exhaustion. The army crossed the River Main near Kassel and reached the Neckar River on June 3. The column then advanced into the valley of the Danube, near Ulm. There, Marlborough linked up with Margrave Louis of Baden, who had been providing flank protection, and the Duke of Wurttemberg, who brought up the remaining segment of the allied army, consisting of Danish cavalry and some additional German infantry. By the 22nd, Marlborough had reached Elchingen, having taken just under five weeks to march some 300 miles from the Netherlands.

Storming Schellenberg

Earlier, on June 10, the duke had met for the first time with Prince Eugene at the village of Mondelsheim, halfway between the Danube and the Rhine. Marlborough suavely played host to his younger comrade, escorting him to dinner at a lavishly set banquet where the generals and their beribboned staffs dined by candlelight and traded toasts of the finest vintage wines. Eugene, wearing his trademark shabby brown coat—Louis had once derided him as “le petite abbe [the little priest]”—periodically dipped into his pocket for a pinch of the finely ground Spanish snuff he sniffed constantly. On June 13, Louis of Baden joined them in Fross Heppach. Among them, the three generals commanded a force of nearly 110,000 men. It was decided that Eugene would return with 28,000 men to the lines of Stollhofen on the Rhine to keep an eye on Villeroi and Tallard and prevent them from going to the aid of the Franco-Bavarian army on the Danube. Meanwhile, Marlborough’s and Baden’s forces, totaling 80,000 men, would combine for a decisive march to the Danube to seek battle with the Bavarian elector and Marsin before they could be reinforced by Louis.

Sensing Marlborough’s destination, the French marshals met at Landau in Alsace on June 13 to rapidly construct an action plan of their own to save Bavaria. Louis’s approval for their plan arrived on June 27. Tallard was to reinforce Marsin and Maximilian on the Danube, moving via the Black Forest with 40 battalions of infantry and 50 squadrons of cavalry. Villeroi was to pin down the allies at Stollhofen, and if the allies moved all their forces to the Danube, he was to join Tallard and General Francois de Coigny with 8,000 men, to protect Alsace. On July 1, Tallard and his army of 35,000 recrossed the Rhine and began their march. Maximilian and Marsin had collected approximately 55,000 men at Ulm, and this force was to be supplemented by Tallard’s army of 30,000 for the invasion.

The Allies needed a base for provisions and a good river crossing. On July 2, Marlborough stormed the key fortress of Schellenberg, located on the heights above the fortified village of Donauworth, part of the defensive line constructed by the legendary Swedish King Adolphus Gustavus in the previous century. Realizing all too well that he was pressed for time, Marlborough disdained a tactical siege and sent his men forward in an all-out attack. Count Jean d’Arco had been sent with 12,000 men from the Franco-Bavarian camp to hold the town, but after a ferocious and bloody battle on the grassy slopes below the town, Schellenberg quickly succumbed, forcing Donauworth to surrender shortly afterward. The British lost 5,374; French losses were even heavier.

The Burning of Bavaria

Following his victory at Schellenberg, Marlborough discerned that the Elector of Bavaria was wavering in his allegiance to Louis XIV. If the inconstant Maximilian saw that his continued hostility to the Habsburg emperor would lead to the destruction of his country, then Marlborough believed Bavaria could be lured away from the French. Since his tactical options were limited, he wanted to force the elector into open battle before Tallard’s reinforcements arrived. Throughout July, Marlborough sent allied troops into Bavaria to burn and destroy buildings and crops. Bavaria had not experienced such ferocious warfare within its borders since the last three years of the Thirty Years’ War, six decades earlier. The brutal Allied policies bore bitter fruit. The Bavarians were terrified of the Allied raiding parties and many fled to the cities for safety, taking with them exaggerated tales of death and destruction.

As expected, Maximilian wavered in his support of the French, until he received a letter from Tallard reassuring him that Tallard was en route through the Black Forest and would soon be in Bavaria with 35,000 men to attack the allied invaders. Marlborough was disappointed that his hopes of negotiating with the elector proved to be nothing but a waste of time—to say nothing of Bavarian property and lives. If Maximilian was determined to remain an enemy, Marlborough decided, then his people would have to suffer the consequences for their master’s stubbornness. He ordered the ravaging of Bavaria to be intensified. Some 372 towns, villages, and farmhouses were demolished in a final spate of cold-blooded ruthlessness.

Meeting Tallard at Blenheim

Meanwhile, Eugene was approaching Marlborough. Both men hoped to bring the enemy to battle. Eugene, on discovering that the French army had slipped away, desired to join Marlborough’s force. Tallard’s maneuvers presented a dilemma for Eugene. If the allies were not to be outnumbered on the Danube, he must either try to cut off Tallard before he could get there or hasten to reinforce Marlborough. However, if he withdrew from the Rhine to the Danube, Villeroi might also make a move south to link up with the elector and Marsin. Eugene compromised. Leaving 12,000 troops behind to guard the lines at Stollhofen, he marched off with the rest of his army to reinforce Marlborough against Tallard. The two men rendezvoused on August 12 at Hochstadt. Marlborough dispatched the troublesome Baden (who tended to question every order) to besiege Ingolstadt with a force of 15,000 men, thereby reducing the allies’ combined strength to about 56,000. Their Franco-Bavarian opponents under the overall command of Tallard, slightly outnumbering them, took up positions on the south bank of the Nebel River and waited for all hell to break loose.

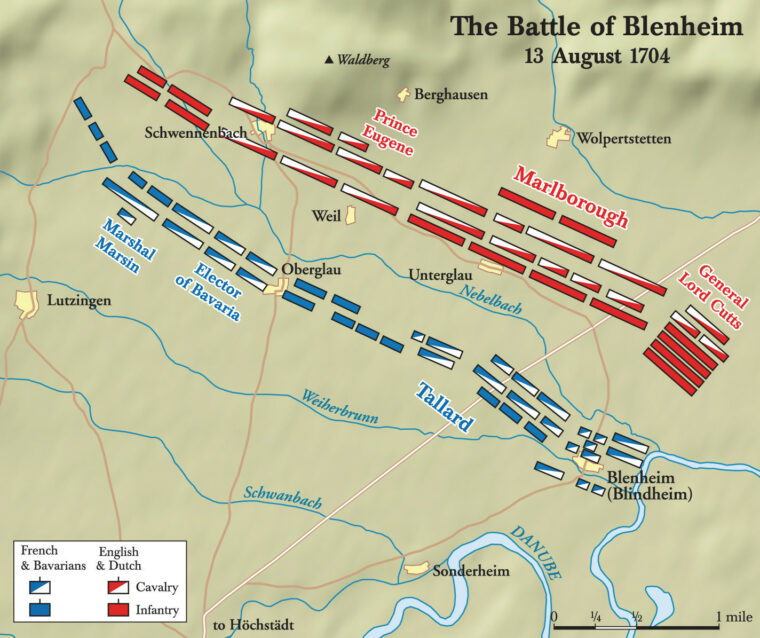

Advancing in eight columns, Marlborough and Eugene spent the morning of August 13 deploying their forces on the north bank of the Nebel. Tallard and Maximilian, meanwhile, moved forward to a new camp, not expecting an allied attack. So certain was the former that the enemy would not advance that he sent a letter to Louis the next morning, declaring firmly that the enemy would no doubt retire on Nordlingen. Tallard’s error may seem blatant, but by the accepted military thinking of the day it was pardonable. The Franco-Bavarians outnumbered their opponents. The strong position they had taken was secured by the Danube River against any attempt to outflank their right and the wooded hills to the north discouraged a turning movement in that direction. The marshy Nebel River was a considerable barrier against frontal attack, and the heavily fortified village of Blenheim anchored the Franco-Bavarian right.

Tallard deployed into position on a wide floodplain between Blenheim to his right and Lutzingen on his left, 21/2 miles away. In the center was a third fortified village, Oberglau. The plain had been planted with vast expanses of wheat, but the wheat had been harvested and the ground was as stubbled as an old soldier’s shaved head. On the allied right, Eugene faced Marsin and Maximilian between Lutzingen and Oberglau, where the ground was considerably less favorable for attack and maneuver, being laced with ditches, hills, thickets, and brambles. Marlborough stood opposite Tallard at Oberglau.

High Risk, High Reward

Marlborough’s battle plan was brilliantly simple: he would attack the enemy where he least expected it—at his strongest point. Pressure on both wings would convince the French and Bavarians that the central thrust was merely a feint and would serve the additional purpose of drawing off enemy strength. Meanwhile, with true English obstinance, Marlborough would crash through the enemy center. To do so, however, he would first have to cross the Nebel River in full view of the French commander. It was a maneuver fraught with high peril and the promise of high rewards.

As the Allies prepared to attack, their tents and baggage were sent back from camp to Reitlingen. The assault started at 2 am on the morning of August 13. A vanguard of 40 squadrons was sent forward toward the enemy position. The main allied force, in nine columns, followed at 3 am, pushing forward toward the Nebel. Mist obscured the march, giving the allies an enormous advantage. At 6 am, Marlborough and Eugene met in Eugene’s tent to finalize plans for the day’s attack before separating their armies into two wings. Marlborough, with 36,000 troops, was to attack Tallard’s equal force on the left, while Eugene, leading 16,000 men, would fight Maximilian’s and Marsin’s combined army of 24,000 troops on the right. By 7 am the fog finally lifted, revealing to the astonished French commanders the attacking army on the far side of the Nebel River, just half a mile distant. Drums beat, trumpets sounded, and cavalry foragers were hastily recalled as the regiments formed up and the initial artillery bombardment began. The individual Franco-Bavarian forces deployed with infantry in the center and cavalry on the wings, the two cavalry wings meeting at Oberglau.

Their left flank was less of a concern to the three Franco-Bavarian commanders. Marsin and Maximilian realized that a full-scale attack was impossible through the woods to their north. Any force would be cut down by their cavalry. However, eight divisions were sent to garrison the village of Oberglau to strengthen its defense. To the left of Oberglau were two lines of the elector’s horse and the bulk of Marsin’s cavalry. Farther to the north, at Lutzingen, there were five elite battalions of Bavarians. This deployment left Tallard with just nine battalions of inexperienced foot soldiers at the center of his line, although he did possess cavalry strength in reserve. Tallard’s plan, hotly contested by the other commanders, was to allow the enemy to cross the Nebel and then drive them back, while attacking their flank from Blenheim. This decision not to defend the river aggressively ultimately would prove fatal to the Franco-Bavarian hopes.

Crossing the Nebel

At 12:30 pm the battle commenced in earnest when Lord John Cutts attacked Blenheim. The village, a warren of interlocking stone houses and stables, was considered impregnable—not that Marlborough minded. He was not so much concerned about taking Blenheim as he was about forcing the French to weaken their reserves by reinforcing their right. Cutts played his part to perfection, repeatedly battering up against Blenheim’s defenses. Four brigades of infantry—two English, one Hessian, and one Hanoverian—assaulted the village, braving heavy musket fire to reach the barricaded walls and streets where the defenders had overturned wagons and thrown furniture from the windows of farmhouses to bar the way. A crack English unit led the way, stabbing through holes in the French defense, firing over parapets, and even attempting to tear open barricades with their bare hands. French reserves, including elite heavy-cavalry gendarmes, arrived in Blenheim and pursued the allied battalions as they fell back. A Scots battalion, the 21st, lost its colors, but a volley by its Hessian allies unseated the gendarmes and allowed an alert Scot to scoop up the lost standard.

Once Cutts had initiated the action at Blenheim, Marlborough and Eugene began their general advance across the Nebel. Prior to the attack, Marlborough had arranged his men in an unusual tactical formation designed to cope with the paramount dangers of crossing water and marching into the face of a strong enemy. He ordered his brother, Charles Churchill, to draw up the infantry into two lines. The first, comprising 17 battalions, was to spearhead the attack, while the second column of 11 battalions would follow in the rear. In between the infantry formations rode 71 squadrons of cavalry, again divided into two lines. The entire force totaled about 23,000 men.

On the allied left-center, Marlborough’s engineers repaired the bridge at Unterglau across the Nebel, which had been damaged by the French. In addition, five mobile pontoon bridges were laid between Unterglau and Blenheim. Separate probing attacks on Blenheim, Oberglau, and Lutzingen were easily repelled. However, the French and Bavarians in the three villages were sufficiently pinned down to enable Marlborough to bring contingents of his cavalry across the Nebel and launch them against the French troops in the open ground between Blenheim and Lutzingen. In the center of the battlefield, Marlborough’s main force crossed the Nebel, the first line of foot followed by a second line of cavalry. In accordance with his plan, Tallard did not attack while the Nebel was being crossed. He belatedly ordered a cavalry charge by the same gendarmes who had been bloodied earlier at Blenheim. The Frenchmen characteristically attacked with élan, but the English cavalry did not break and run; instead, it deployed into three groups and fell on the French flanks and rear. Tallard watched, dismayed, as the red-coated dragoons drove off his horsemen.

Once across the Nebel, Marlborough deployed his men in a unique formation: two lines of infantry between two lines of cavalry. This allowed them to repel repeated French cavalry charges. The allies continued to take heavy cannon fire. At one point Marlborough, attempting to inspire his men by leading from the front, was almost killed when a cannonball kicked under his horse’s feet. To the surprise and delight of his foot soldiers, the duke emerged unscathed through a cloud of dust with the Order of the Garter still sparkling on his gold-and-scarlet coat.

While Marlborough crossed the Nebel in the center, Eugene mounted an assault on the allied right. The rough ground prevented him from making much headway, although Marlborough was not greatly alarmed—his plan to divert enemy attention was working. At 3 pm, the French mounted a fierce counterattack at Oberglau, spearheaded by the fiery “Wild Geese,” an Irish brigade serving in the French ranks against the hated English. Marlborough rode to the scene and dispatched a message to Eugene calling for reinforcements. Eugene was having troubles of his own, but he immediately ordered his cuirassiers to strike the French flank and help repel the breakthrough. As quickly as it had arisen, the French counterattack fizzled. Marlborough was saved.

Breakthrough in the Center

By 5:30 pm, following a quick but effective volley by 40 massed cannons, the allies breached Tallard’s center, their forces streaming through the gap beyond the Nebel. Marlborough relied on his infantry in the intense hand-to-hand fighting. There were no French forays from Blenheim on Marlborough’s flank, as Tallard had planned, since Cutts blocked them effectively. Meanwhile, on Eugene’s wing, Marsin and Maximilian had repeatedly thrown the Allies back across the Nebel. However, Eugene’s forceful attacks prevented them from supporting Tallard elsewhere.

In response to Marlborough’s breakthrough, Marsin’s regiments fell back toward Oberglau, leaving Tallard’s force isolated in the face of another charge by Marlborough’s cavalry squadrons. Tallard’s own cavalry fled behind Blenheim and on toward the Danube. Marlborough’s troops swept to the rear of Blenheim, surrounding the large French garrison. Charles Churchill was preparing to assault the village when the French proposed a parley. They sought terms that would enable their regiments to leave with honor, but the allies would only accept complete submission. Finally, 24 battalions of French foot and four regiments of dragoons surrendered to Marlborough. The defeat of the French and Bavarian army was complete. While still in the saddle, Marlborough scribbled a hasty note to his wife, Sarah, announcing a “glorious victory.” It was that.

In the confusion, Tallard was wounded and captured, and many of his men drowned in their attempt to escape across the Danube. Marsin and Maximilian, witnessing the collapse of Tallard’s army, set fire to Oberglau and Lutzingen and retreated to the northwest. Tallard lived for seven years as a prisoner in England. Upon his return to France in 1712, he was greeted with kindness by Louis XIV and accepted back at court. Casualties at Blenheim were very high owing to the exchange of fire between nearby lines of closely packed troops, the use of artillery against such formations, and cavalry engagements relying on cold steel. Marlborough and Eugene suffered 12,000 casualties, while Franco-Bavarian losses totaled 38,000, 15,000 of them prisoners. Forty-three percent of all troops engaged at Blenheim had been killed, wounded, or taken prisoner.

The victory gave the allies the initiative. The safety of Vienna was assured, and the French armies were driven from Germany. Maximilian was forced into exile, and his state was annexed by the Austrian Empire. The Battle of Blenheim marked the first great defeat of a French army in the field during the reign of Louis XIV, and it strengthened the resolve of the German princes who opposed him as it reinvigorated the war party in the Netherlands. In Spain, the battle caused the defection of some influential noblemen from Philip V. Most important, it stirred the English nation to unparalleled outbursts of pride and enthusiasm.

The Outcome: The Treaty of Utrecht

Blenheim was followed by the conquest of southern Germany, as Bavaria was taken out of the war. After the battle and its subsequent retreat to the Rhine, the Franco-Bavarian army was largely ineffective. The allies were able to retake the major fortresses of Ulm, Ingolstadt, and Landau before the close of the year. Marlborough won other battles, but none had the dramatic impact of Blenheim, in part because that victory preserved the anti-French alliance. He benefited personally from the battle as well, when Parliament provided the funds with which he built a beautiful and impressive palace named after his great victory.

The French defeat was kept from Louis for some time, and when he was informed he became quite depressed because this was his first loss of consequence. Blenheim shattered the myth of French invincibility that had developed during the previous 50 years, and the French were thrown onto the defensive. There followed further allied victories at Ramilles and Oudenarde in the Spanish Netherlands. During the bitter winter of 1708-1709, France seemed on the brink of defeat, but Louis again rallied his people. A new army under General Claude-Louis-Hector Villars met Marlborough and Eugene at Malplaquet on September 11, 1709. The French lost 17,000 men, and estimates of allied casualties ranged from 8,000 to 18,000, the latter figure being more likely. The allies held the field, but the French retreated in good order, resulting in a virtual stalemate between the two sides. At length, Louis made private overtures for peace. The English signed the Treaty of Utrecht with France in 1713.

The treaty brought large colonial gains for England, while the Dutch gained the fortifications along the French border, and the Austrians obtained Naples, Sardinia, and Milan. Brandenburg-Prussia officially became a kingdom, and Savoy got control of Sicily. Louis ruled a war-weary France until his health broke in 1715. Suffering from fever and gangrene, he mustered enough strength to say, “I depart, France remains,” before dying on September 1, 1715, at Versailles. Louis XIV’s grandson retained the throne of Spain, but that nation was shorn of its European possessions. The greatest winners were the British, who had cemented their position as a great continental land power. The treaty left France and England as the two most vigorous nations of Europe.

In 1933, Marlborough’s direct descendant, Winston Churchill, wrote with pardonable pride: “The triumph of the France of Louis XIV would have warped and restricted the development of the freedom we now enjoy, even more than the domination of Napoleon or of the German Kaiser. Marlborough commanded the armies of Europe against France for ten campaigns. He fought four great battles and many important actions. It is the common boast of his champions that he never fought a battle that he did not win, nor besieged a fortress he did not take. Amid all the chances and baffling accidents of war he produced victory with almost mechanical certainty. He quitted war invincible; and no sooner was his guiding hand withdrawn than disaster overtook the armies he had led. Successive generations have not ceased to name him with Hannibal and Caesar. Until the advent of Napoleon no commander wielded such widespread power in Europe. Upon his person centered the union of nearly 20 confederate states. He held the Grand Alliance together no less by his diplomacy than by his victories.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments