By David H. Lippmann

Once again, the Japanese regarded an upcoming naval engagement as the “decisive battle,” but it had been two years since her aircraft carriers and battleships had emerged from their Inland Sea lairs to menace the United States Navy. Many of the legendary aircraft carriers and highly-trained aviators that had struck the blows at Pearl Harbor and other early battles were in watery graves, and their replacements were new warships fresh off the production line and poorly trained crews and airmen. Most importantly, thanks to the increasingly effective American submarine campaign, Japan’s economy and Navy were choking for lack of oil.

None of this mattered to Admiral Soemu Toyoda, the commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet. By June 1944, the Japanese outlook was looking increasingly bleak to its most senior officers. British troops had broken the sieges at Imphal and Kohima, the Chinese front was an unending quagmire, and now the Americans were aiming a steel fist at the Mariana Islands, the chief punch of which was 15 aircraft carriers, seven modern battleships, and three Marine divisions.

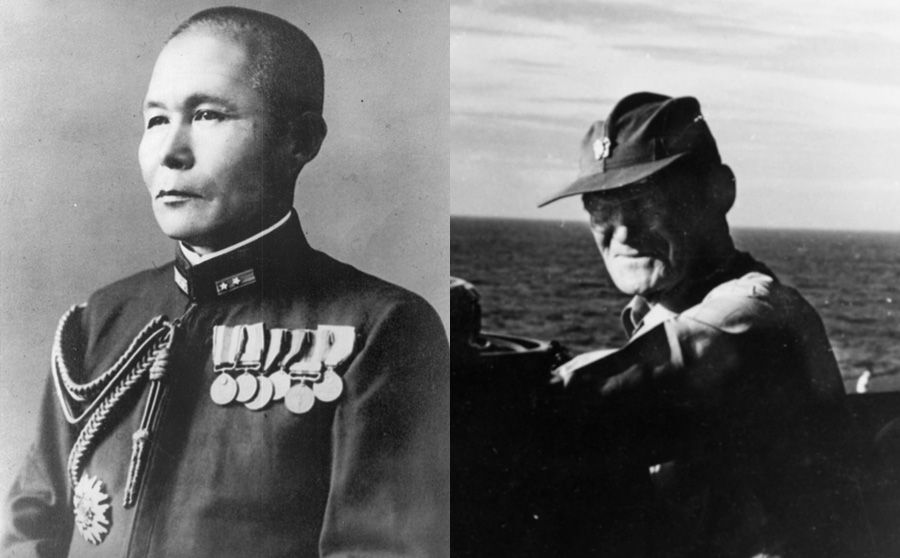

According to Japanese naval strategy as far back as the 1930s, the Marianas chain was where the decisive battle between the emperor’s ships and the American fleet would take place; but those prewar plans, calling for battleships slugging it out in a fire-away-Flanagan shootout, had been erased by the dominance of the aircraft carrier and submarine. A new idea was needed, and Toyoda had one: commit the Imperial Navy’s best ships, organized into the 1st Mobile Fleet under 57-year-old top airman Vice Admiral Jisaburo Ozawa, to a major fleet engagement, the A-Go Plan.

To solve their oil problem, the Japanese massed these ships at Borneo’s Tawi Tawi anchorage, close to the Borneo oilfields. But Tawi Tawi was heavily surveilled by American submarines, which reported the Japanese fleet massing there. This assembly of Japanese ships alerted the U.S. Pacific Fleet but did not prevent Vice Admiral Raymond A. Spruance, commanding the U.S. Fifth Fleet, from heading for the first Mariana island to be invaded, Saipan, and treating it to heavy air and gun bombardment before sending the Marines ashore to invade the island on June 15.

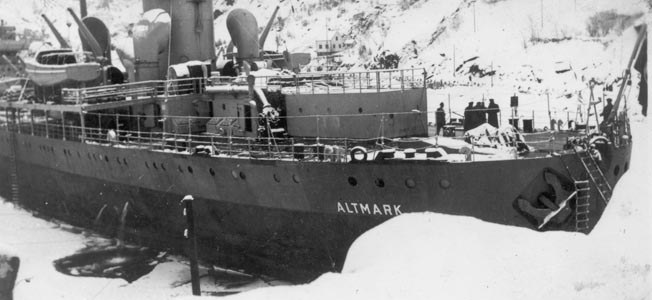

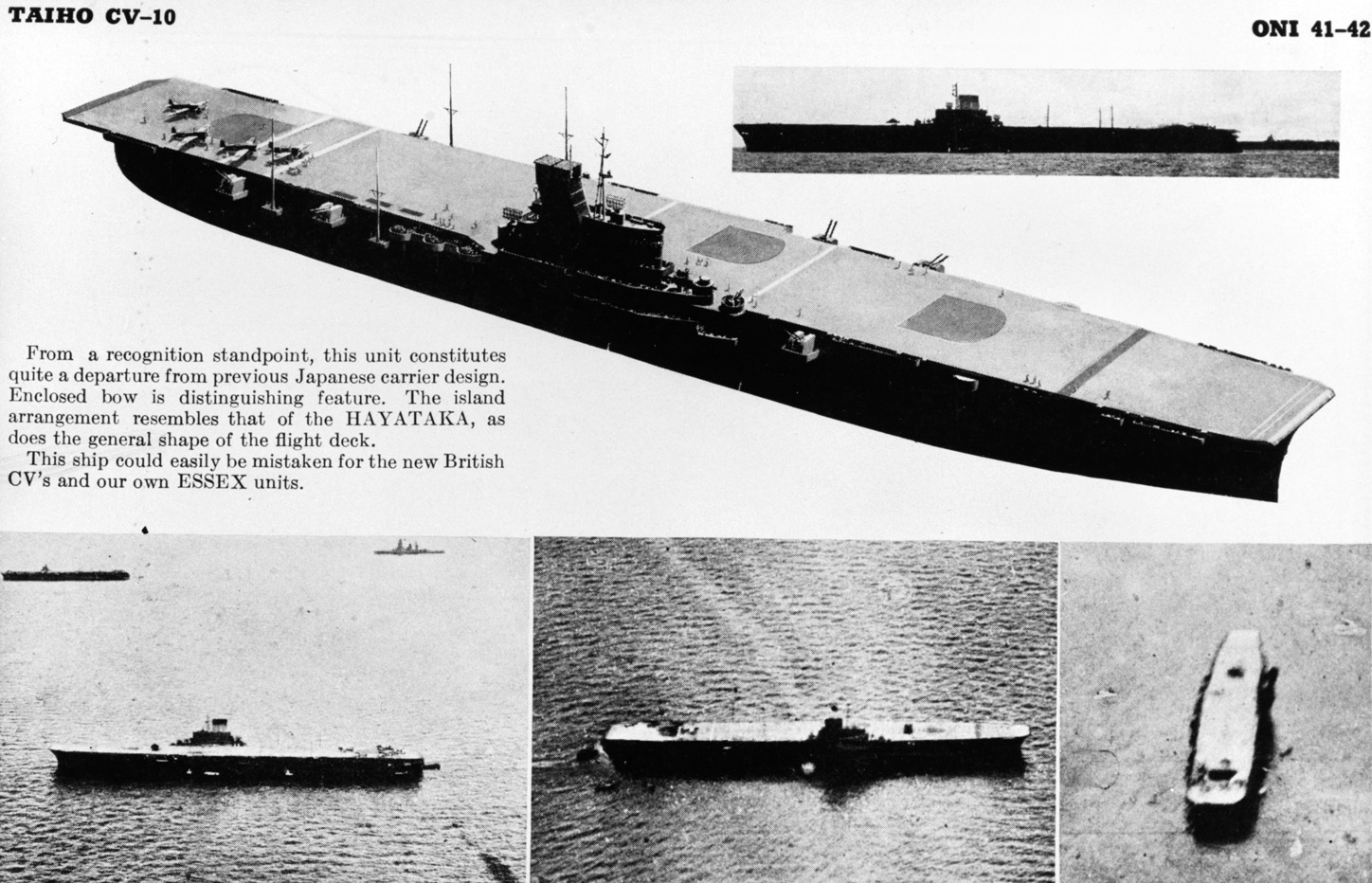

The Japanese were already coming. On June 11, Ozawa took his ships to sea. It was a colorful force: the two most powerful battleships in the world, Yamato and Musashi, packing 18-inch guns; the fleet carriers Shokaku and Zuikaku, which had delivered the first blows at Pearl Harbor; the light carriers Hiyo and Junyo, which were converted liners; the light carriers Chitose and Chiyoda, converted from seaplane tenders; and the new carrier Taiho, which incorporated everything the Japanese had learned from the damage-control failures that had resulted in their carriers being sunk at Midway two years before.

On June 15, the submarine USS Flying Fish spotted them on the move and reported it. Spruance prepped for naval battle.

Unlike at Midway, Spruance would have vast advantages: 15 carriers to Ozawa’s nine; seven battleships to Japan’s five; 21 cruisers to Ozawa’s 13, and 69 destroyers to Ozawa’s 28. More importantly, the Americans had 891 planes on their carrier decks to Ozawa’s 430. Ozawa had one other trump card, though: 400 land-based planes at islands including Iwo Jima and Saipan, which could tip the scales of the battle.

Despite its weaknesses in training, fuel, and equipment, Ozawa was going to sea with the most powerful force Japan would ever deploy on an ocean—50 percent larger than the force that had attacked Pearl Harbor—headed by Taiho, a well-constructed ship with an armored flight deck and anti-torpedo blister. Everyone believed victory was assured, from the pilots, who believed their aircraft would shatter the American fleet, to Admiral Matome Ugaki, commanding the battleships, who wrote in his diary, “Can it be that we’ll fail to win with this mighty force? No! It can’t be!”

on the Japanese.

The American naval aviators considered themselves, justifiably, a military elite. Their number included future president George H.W. Bush, then serving on the light carrier USS San Jacinto. They were rigorously trained for up to two years in the United States by veteran combat aviators who shared their experiences, and they practiced carrier takeoffs and landings—one of the most difficult tasks a naval aviator faced—on two paddle-wheeled, coal-powered cruise liners that had been turned into immense training carriers. Few of them had seen actual battle; only the aviators of USS Enterprise, which had experienced three such engagements, had done so.

Despite their combat inexperience, they had massive advantages over the Japanese beyond mere numbers. The legendary Japanese Mitsubishi A6M Zero, once the terror of the skies, was now inferior to American F6F Hellcat fighters. The American TBM Avenger torpedo bomber was more than a match for the new Japanese Nakajima 6N Jill torpedo bomber, as well. The rugged and veteran SBD Dauntless dive bomber was superior to Japan’s Yokusuka D4Y Judy.

As the Japanese advanced, they immediately ran into trouble. American submarines homed in on the 1st Mobile Fleet, and their torpedoes crippled two supply ships and sank a destroyer. The Japanese sent submarines ahead of the battle force to scout the Americans, and U.S. destroyers, intercepting their radio transmissions, sank 17 of them. The destroyer escort England alone sank six Japanese submarines in 13 days.

As Ozawa headed east, so did Spruance. While Marines struggled on Saipan’s shores, Japanese and American reconnaissance planes flew across the ocean south of Iwo Jima, looking for each others’ fleets.

During this long wait, Spruance paced the deck of his flagship, Indianapolis, pondering his situation. It seemed to him that Ozawa was merely probing, hoping to lure the Americans to a position west of Saipan so that they could do a flanking end-run around the carriers and hit the amphibious forces offshore. Spruance realized he could not shove off without leaving the Marines ashore in jeopardy, a lesson learned at Guadalcanal in 1942, when the early departure of U.S. transports and their unloaded supplies nearly doomed the invading Marines.

Spruance decided that he would use the strategy of Togo before Tsushima: of wait for the Japanese to attack him, relying on his technological advantages— radar, fighter direction, superior guns, and aircraft—as well as his superior numbers to defeat them. He told the commander of his carrier forces, Vice Admiral Marc “Pete” Mitscher, and the commander of his battle line, Vice Admiral Willis “Ching Chong China” Lee, that while they would be in command of their own groups, Spruance would hold them on a short leash. In the meantime, Spruance wanted both forces to continue to support the assault on Saipan and bomb Japanese airbases on Guam and Tinian.

The fleet would stay close to Saipan and let the Japanese come to them. Once they did, Spruance ordered, “Our air will first knock out enemy carriers, then will attack enemy battleships and cruisers. Battle line will destroy enemy fleet either by fleet action if the enemy elects to fight or by sinking slowed or crippled ships if the enemy retreats. Action against the retreating enemy must be pushed vigorously by all hands to ensure complete destruction of his fleet.”

Mitscher was not happy. A carrier veteran, he was eager to strike first, as were most of his officers. Regarding Spruance as a battleship admiral out of his league, they urged Mitscher to dispute the decision.

On the other hand, Lee was ready: given the order “Form battle line,” he did so with alacrity, but had a different worry. From his experience with leading battleships into action against the Japanese off Guadalcanal, he knew they were ferocious night fighters. Worse, some of his battleships and cruisers had fairly new crews and were still inexperienced in handling night actions. He signaled Mitscher: “Do not (repeat not) believe we should seek night engagement. Possible advantages in radar more than offset by difficulties of communications and lack of training in fleet tactics at night. Would press pursuit of damaged or fleeing enemy, however, at any time.”

On the evening of June 18, American codebreakers deciphered a fresh message from Ozawa to his air bases in the Marianas, and direction finders located the 1st Mobile Fleet 355 miles west-southwest of Spruance’s ships. Mitscher proposed to Spruance that they head west at 1:30 am and put Task Force 58 in position to attack Ozawa at dawn. For an hour, Spruance pondered the situation with his staff. The situation was made confused by a report from the submarine Stingray that the Japanese were further south and east, which could have been the flanking force. Finally, Spruance signaled Mitscher: “Change proposed does not appear advisable … end run by other carrier groups remains possibility and should not be overlooked.”

On Mitscher’s flagship, the carrier Lexington, Mitscher’s staff exploded, demanding that he go over Spruance’s head and have him relieved. A Yorktown officer diaried: “The Navy brass turned yellow: no fight, no guts … Spruance branded every man in TF-58 a coward tonight. I hope historians fry him in oil.”

An utterly calm Spruance, however, went to bed after giving his orders. In Task Force 58’s hangar decks, airmen stowed bombs and torpedoes, while readying fighters for the morning.

At 3 am on June 19, boatswain’s whistles, Marine bugle calls, gongs, buzzers, and 1MC (shipboard public-address system) announcements on the American ships ordered the crews to general quarters. Sailors dogged hatches to set “Condition Z,” secured battle shutters over portholes, and donned Mae West life vests and tin hats as the sun rose to commence a day of east winds, mild seas, and clear skies, granting no cover from Japanese aircraft.

Sailing 158 miles west-southwest of Saipan, Task Force 58 was divided into three carrier forces and their escorts, with the battle line arrayed astern to shield the flight decks from surface attack from the west with their 16-inch guns or air attack with their 40mm and 20mm guns.

On the opposite side, Ozawa had to rely on his reconnaissance planes to spot the American fleet, which they did on the 18th, as they had longer range than American search planes. Moving up to attack, Ozawa put his light carriers, Chitose, Chiyoda, and Zuiho forward into the van group along with Yamato and Musashi, while keeping the six heavier carriers behind in the main group. This was standard Japanese tactics since Pearl Harbor, an intricate naval ballet that used a decoy force to lure in the main American air strength while a main force pulverized the American fleet.

By 4:15 am on the 19th, Ozawa was ready to hurl more than 300 planes at the Americans, who still did not know Ozawa’s position. Tactically, it was the opposite of the Battle of Midway, where the Americans had a small force compared to the Japanese but the Japanese did not know where they were. This time the Americans had an overwhelming force but did not know where the Japanese were. But there was one critical similarity: the American commander Raymond Spruance.

As the sun rose, the U.S. Fifth Fleet steamed eastward into the wind to enable carriers to launch planes, periodically zigzagging back to stay on top of Saipan. At 10:23 am, Spruance suggested to Mitscher that if no enemy ships turned up, he could attack Japanese bases on Rota and Guam, as Ozawa was likely to send his planes there to rearm, refuel, and attack the Fifth Fleet.

Meanwhile, Mitscher launched his fighters on sweeps and combat air patrols over Guam and met land-based planes taking off to attack Task Force 58. American fighters accounted for 30 fighters and five bombers there.

At 4:45 am, Ozawa began launching 30 search planes, and one of them picked out Mitscher’s ships at 7:15 am. Seven others were shot down by Mitscher’s combat air patrol.

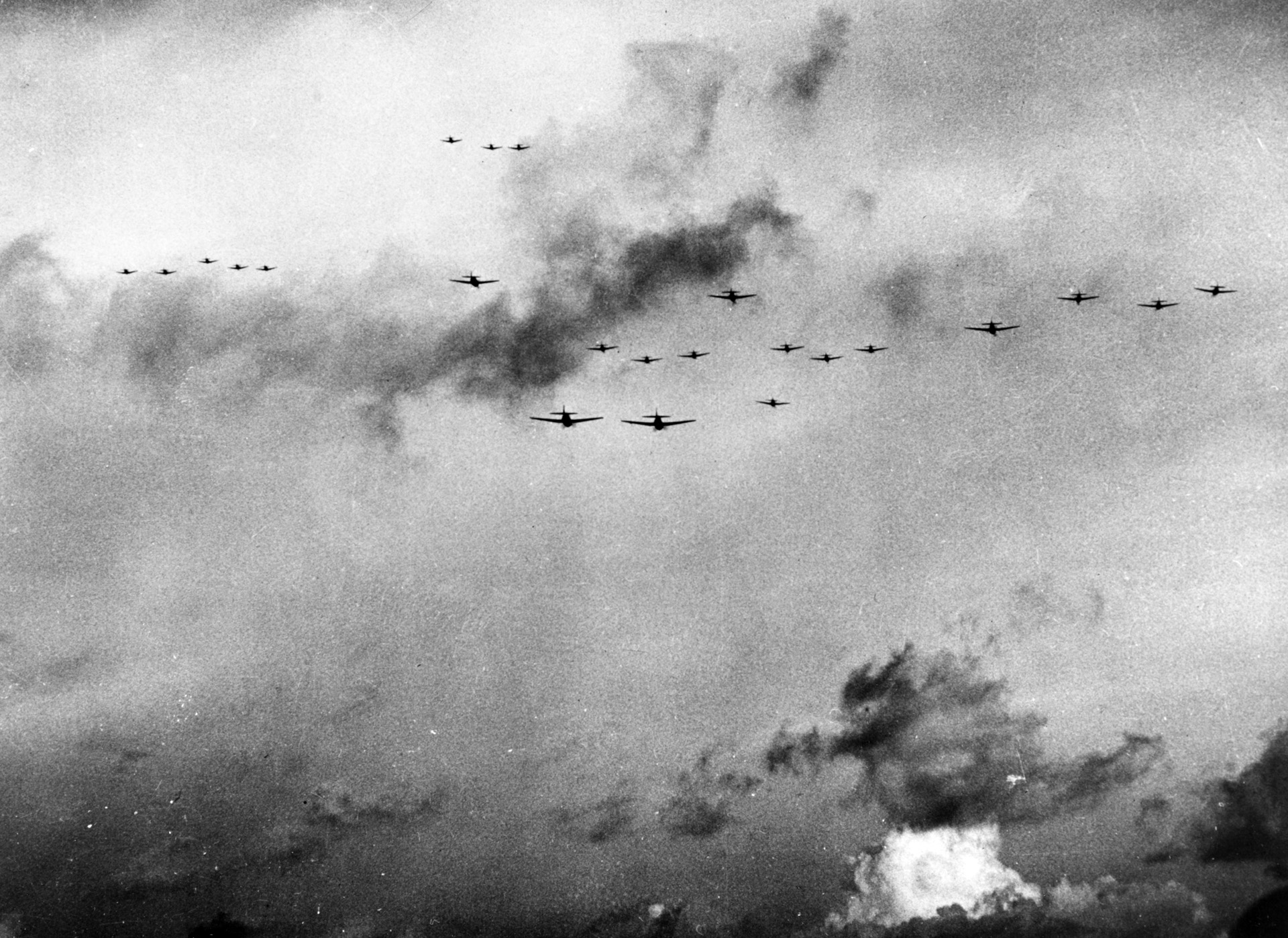

Nonetheless, Ozawa got moving. His first raid—Raid One to the Americans—launched at 8:30 am from the van force, consisting of 45 Zeros configured as bombers, eight Jill torpedo planes, and 16 Zero fighters for cover. It numbered 69 planes in all.

At 10:05 am, the battleship Alabama’s radar registered the incoming strike at 125 miles west, 24,000 feet or higher. Ozawa’s strike force had arrived right on time. All ships that had not done so went to general quarters. Among the sailors who raced to his station on Alabama was the gun captain of a 40mm antiaircraft gun named Robert Feller. In peacetime, he was one of the greatest pitchers in the history of Major League baseball. He could have stayed on shore, playing for Navy teams to boost morale, but he asked for and got sea duty to avoid an appearance of favoritism for star athletes.

Mitscher began launching his reserve fighter aircraft and summoned his fighters back from Guam with the signal, “Hey, Rube!” The message was the old circus cry for help. Fighter pilots leaped from the chairs in their ready rooms, gulped coffee, and ran onto their flight decks, jumping into the first available F6F Hellcat fighter. Without stopping to rendezvous, they headed west, vectored in by American fighter directors headed by Lieutenant Joe Eggert.

When the Japanese closed to 72 miles, they began to orbit as their group commanders had ordered, which took 15 minutes. Fighting 15 from Essex commanded by Commander Charles W. Brewer, was first in. Like many of his teammates, he yelled, “Tally Ho!” into his radio when he had a visual sighting of the enemy.

The Hellcats bounced the Japanese and broke apart their neat formation. Brewer pursued the formation leader and opened fire at 800 feet, exploding the Zero. He flew through the burning wreckage and shot up another Zeke, snapping off the enemy’s wing. The Zero plunged, flaming, into the sea. Brewer hit another Zero with a no-deflection shot at 400 feet, and it too fell, burning, into the sea. At that moment, Brewer saw a Zero diving on him. Brewer pulled his plane around, got into a hot fight with the Zero, finally got on his tail, and snapped short bursts on him. The Zero pilot tried some half-rolls, barrel rolls, and wingovers, but they were not enough. The plane caught fire and spiraled into the ocean, a four-for-four day for Brewer.

More fighters of squadron VF-25 from the carrier Cowpens swooped in, joined by planes from Hornet, Princeton, and Cabot, as well as Monterrey, whose assistant navigator was future president Gerald R. Ford. The American planes worked over the Japanese with brutal efficiency. In the perfect sky, planes spewed contrails behind them, and Ernest Snowden, the leader of Lexington’s fighter group, thought it was just like the commercial skywriting he had seen before the war.

Onboard Lexington, Lieutenant Alex Vraciu, a Chicago-born ace who at that point had 12 kills to his credit, hopped into an older F6F, and the plane’s engine splattered oil into his windshield, obscuring his vision. To make matters worse, the radio circuits were jammed with idle chatter and instructions that should have been given in the ready rooms.

Vraciu peered through his oil-covered canopy and saw many hostile planes on an opposite course, thousands of feet below him, but lacked targets for the moment (his buddies were doing too good of a job).

Down below, Mitscher launched his torpedo and dive bombers to keep them away from the engagement. Now the survivors of Raid One’s 69 planes approached the American battleships and carriers. Six had been lost at sea in the long overwater flights, others had gotten lost and flown to Guam, and most had been shot down in the dogfights.

The battleships were drawn up in a circle with Indiana acting as a formation guide in the center. Lee himself ran the operation from his usual flagship, Washington.

The surviving bombers headed for the battleship South Dakota, which had enjoyed a mixed record in the war. She had fought with great valor at Santa Cruz, the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, and other battles, but crews of other warships regarded her as a seagoing menace to their own side, as she seemed to bring bad luck wherever she went. At the height of Second Guadalcanal, for example, she suffered an electrical power failure from overloaded circuits, which rendered her useless and a danger to the other American vessels. One of her lieutenants was young Sargent Shriver, who would marry Eunice Kennedy, John F. Kennedy’s sister, and become first director of the Peace Corps in 1961.

Japanese planes swung down on South Dakota and her escorts, giving Seaman James J. Fahey on the light cruiser Montpelier his first up-close and personal look at an enemy air attack. He wrote in his diary, “Jap planes were falling all around us, and the sky was full of bursting shells. Big puffs of smoke could be seen everywhere … Bombs were falling very close to the ships, big sprays of water could be seen, and Jap planes splashing into the water.”

American antiaircraft guns, including Bob Feller’s 40mm mount on Alabama, chopped up the attackers. “For 13 hours, the Japanese threw every plane it could at our task force,” Feller wrote later. “All of us on the Alabama fought them off. I was gun captain on a quad 40 with about 25 sailors throwing ammunition. We fired eight rounds a second and opened up at 5,000 yards. For all 13 hours, we stayed at our guns. We had our C rations to eat and we just stayed there and waited for whatever was going to happen. On the sky just above the sea horizon, I spotted dots, four of them. Could be anything, could be Hellcats. I blinked hard. These were twin-engine, high-tail. They were Betties. When they got close enough, we opened fire. The sky turned black from smoke and bright white from tracer fire. The smell of cordite overpowered the sea air. The Japanese sent bombers, and we sent up a wall of white-hot metal to meet them. I didn’t feel fear or a moment’s indecision. I kept my four guns blazing. Two of the Betties disintegrated, and the others ran.”

Lieutenant (j.g.) Rollo Ross on Washington directed the battleship’s antiaircraft batteries. “We usually expected air attacks from groups of planes coming at you from the same general direction, most out of the sun and low down on the horizon,” he said later. “But the Turkey Shoot was different. They seemed to come in ones and twos from every direction. Our own fighters had given them such a rough time on the way in that the survivors were highly disorganized by the time they arrived over us. The attacks just seemed to go on and on without end. All the time, it seemed there was an aircraft in sight some place and one of the ships in the formation was firing at it. Our own planes kept clear of us pretty well, so that by and large, anyone who came within range was usually a Jap. I have no idea how many planes were shot down or how many times we fired. I was so busy that the whole thing just became a blur, but it was obvious who had the upper hand.”

In the combat information centers of the American ships, sailors and officers fought the battle in windowless compartments, scrutinizing radar screens and listening to reports from fighter pilots, antiaircraft gunners, and lookouts over headsets. Sailors tracked incoming raiders on glass boards, using red grease pencils to follow Japanese “bogeys” and white pencils for American aircraft. They could tell the difference by the “identification-friend-or-foe” gear the U.S. planes carried. Every time a radar operator sang out a new bearing, the trackers changed the data. As the Japanese closed in, there were fewer planes on the scopes, and increasingly cheery calls from the American fighter pilots above.

Not all the news was good, though.

One of the Japanese planes maintained South Dakota’s history of bad luck by hurling a 551-pound bomb on her forward superstructure, which blew a large hole in the ship, damaging wiring and piping, as well as the captain’s and admiral’s quarters, while knocking out a 40mm antiaircraft gun, killing 27 crewmen and wounding 24 others. South Dakota gunners claimed they sent their attacker spiraling into the sea, but gunners on Alabama claimed the Japanese plane got away, which set up more bad blood between “Sodak” sailors and their shipmates.

Lieutenant (j.g.) Frederick R. Steiglitz, flying an F6F from Cowpens, reported over radio that he had shot down a plane and signaled visually that he had downed another, but never returned to “Mighty Moo” to confirm the score. With engine damage, he had to splash into the drink. He was seen climbing into his life raft but was never recovered.

Despite these losses, the few Japanese that broke through the defenses overall did little damage. One dropped a bomb that landed a few feet from the heavy cruiser Minneapolis’ starboard side. The shock of the explosion ruptured some gas, oil, and water lines, sparking a fire.

Ultimately, none got near the carriers, and at 10:57 am, Eggert reported that the radar screens were clear. Raid One’s survivors assembled to return home. There were only eight fighters, 13 fighter-bombers, and six torpedo bombers—27 planes left of 69 attackers. The Americans had suffered the 27 dead on South Dakota and four pilots lost.

Mitscher, aware that this could not be the main raid, ordered his fighters to recover, re-arm, and refuel. Crewmen in blue plane-handler vests patched holes in F6Fs while aviators sipped coffee and were debriefed by their superiors.

Meanwhile, the torpedo and dive bombers still orbited to the east, gulping fuel, seeking orders. Mitscher eventually ordered Enterprise’s torpedo bombers to locate the Japanese fleet, after which the rest of the airmen would follow, once contact was established, but this would have to wait. Ten minutes after Eggert’s screens were cleared, Raid Two arrived.

Ozawa’s Raid Two had begun launching shortly after 8 am. The attack force, consisting of 35 dive bombers, 27 torpedo bombers, and 48 fighters, immediately ran into trouble. As the planes roared over Admiral Takeo Kurita’s van force, his jumpy antiaircraft gunners opened fire, shooting down two planes and damaging eight, forcing them to turn back.

The Japanese formation was highly ragged, reflecting the declining quality of their airmen. The planes flew at varying cruising speeds, drifting into smaller groups, planes losing contact with their leaders.

In his Aichi D3A Val dive bomber, Lt. Cdr. Zenji Abe, a veteran of Pearl Harbor and Midway—a rare breed, indeed—flew on, mentally and physically exhausted. “I was suffering from a very unusual physical condition caused by prolonged fatigue,” he said later, “and felt I was in a plane being flown by somebody else.” As his plane droned on, he saw fewer planes in his ragged formation. He assumed those missing had either turned back or “dived into the sea from mental confusion.”

Abe and his fellow airmen reached the American fleet at 10:27 and were greeted by a dozen Hellcats from Essex led by Commander David McCampbell, a sharp Alabama-born pilot with movie star looks. Even before McCampbell and his men charged into the Japanese attack force, though, the Japanese fleet was already facing disaster.

As Taiho launched her planes, one of the pilots, Warrant Officer Sakio Komatsu, noticed something odd in the ocean below him: an incoming torpedo wake headed straight for his carrier. With dexterity, coolness, and bushido valor, he banked hard and dived in its path, slamming into the fish and sacrificing his life to save Taiho from the torpedo. It was heroic, but it was not enough. Five more torpedoes raced for the carrier.

The source of this attack was one of America’s humblest and most powerful weapons: the 1,525-ton, Gato-class submarine Albacore, under Commander Jim Blanchard. One of the submarines on picket duty, she had been ordered on June 18 to head 100 miles south at full speed to intercept the Japanese fleet. At 7 am, Albacore was spotted on the surface by a Japanese plane, and Blanchard promptly went into a dive, assuming that the Japanese fleet was nearby.

He was right. At 7:50 am, Albacore sighted ships to the west, and Blanchard ordered “Battle stations submerged!” With red lights on to make it easier to read dials and sonar scopes, Blanchard peered through his periscope and saw a submariner’s dream, a carrier headed east, at 70 degrees port, seven miles away. “Left full rudder! All ahead flank!” he ordered.

Albacore raced for an intercept position, but Blanchard realized the carrier would outrun him. He did a 360-spin with the periscope and suddenly ordered, “Right full rudder! Another flattop! This one’s coming right down the groove! All we have to do is wait for him!”

Albacore headed straight on a new course for Taiho. Blanchard raised his periscope again and said, “Looks good! All clear around! Nobody close aboard! Make ready all tubes!” With Albacore deep inside the Japanese formation, it was time to attack.

Blanchard had 10 seconds to figure out what to do. “Up periscope! Continuous bearing!” he yelled. “I’m going to stay right on him!” When Albacore was at the firing point, Blanchard shouted, “Fire one!” In short order, Albacore launched six torpedoes, streaking straight for Taiho.

Blanchard then spun his periscope and yelled, “Take her down! Take her down fast! All ahead full!”

Komatsu dived on the first one, ending that torpedo’s run and his life. As Albacore sprinted into deep waters, the five remaining torpedoes charged in. Four missed astern, but one scored a hit near Taiho’s aviation fuel tanks.

The hit set off an explosion that provided Blanchard and his crew with knowledge that they had done some damage after all, but now two Japanese destroyers charged in, hurling depth charges in rapid sequence. Blanchard whipped out his stopwatch, while keeping an eye on the depth gauge. The deeper Albacore got, the better her chance of surviving the Japanese counterattack.

Six depths charges went off near Albacore, shaking the submarine, shattering light bulbs, flinging men to the deck. The destroyer turned around on her run and began another attack. American submarine skipper and historian Ed Beach would note, “Many German submarines in similar circumstances simply surfaced and gave up the fight, but not United States submariners, and not Jim Blanchard.”

Albacore, deeply submerged at maximum depth, crept along, seeking an opening. The break came sooner than expected; by noon, Blanchard and his submarine were well away from their target.

Up above, Taiho was facing the chore and challenge of a lone torpedo hit that seemed to have done little more than create a geyser of water, smoke, and debris. Taiho slowed one knot, the forward elevator was jammed in the “up” position, and no fires were reported to damage control central. Taiho sailed on. Nobody seemed to be aware that the hit had ruptured gasoline and oil lines—carriers usually smelled of gasoline and oil. Up on his flag bridge, Ozawa himself was confident that his new flagship’s design could handle any hit from an American submarine.

Meanwhile, Raid Two plunged on toward Mitscher’s carriers. At 11:07 am, Eggert vectored in McCampbell’s Essex Hellcats from above the battleships, and they dived from 25,000 feet into the oncoming Japanese, spotting nearly 100 Zero and Judy attack planes 45 miles from the task force. McCampbell wasted no time. He took his planes into a fast attack pass from the side to scatter the enemy. His .50-caliber machine guns immediately incinerated a Judy bomber—many Japanese planes lacked self-sealing fuel tanks—and he flew through the formation to the other side. There, he jockeyed for position on another Judy and sent it smoking, claiming a “probable kill.”

Now he spotted the formation leader and his two wingmen. This time, he hit the leader’s wingman from 7 o’clock high, and exploded that plane. McCampbell swung in on the left of the leading Judy, firing bullets into it until it “burned furiously and spiraled downward out of control.” McCampbell saw that his guns were suffering stoppages, so he pulled out to recharge them, then returned to the battle.

By now, the Japanese formation had been shredded by American planes, but the survivors were showing bushido determination. McCampbell saw another formation leader and attacked, but only the starboard guns fired, and McCampbell was thrown into a wild skid. The Judy plunged into a fast dive, but McCampbell stayed on its tail, firing short bursts with his working guns. The Judy pulled up and slammed into the sea.

With his guns jammed and useless, but with five kills and one probable in this single battle, McCampbell headed for Essex. He was now an ace and would finish the war with 34 aerial victories, the Navy’s top killer, appearing on the covers of magazines, his name gracing a Burke-class destroyer 70 years later.

Meanwhile, Essex’s VF-15 fighter squadron shredded the Japanese but took some pain in return. Ensign J.W. Power was wounded by the Zero he destroyed. Ensign C.W. Plant found 150 holes in his plane when he landed on Essex.

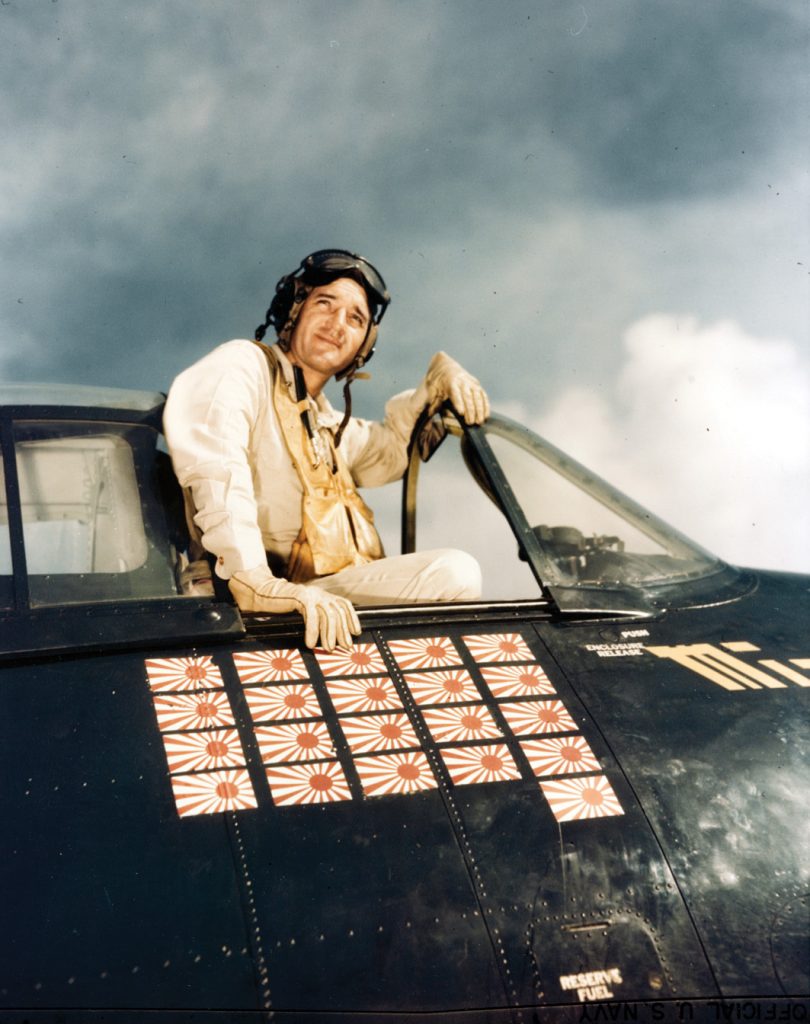

Fortunately, help was coming for the Essex fighters, as the rest of the carrier planes charged in, led by Vraciu, whose muck-covered windshield had been cleaned in the lull. He shot down a Judy from about 200 feet away, then saw two more dead ahead. Vraciu maneuvered his F6F behind the two planes and opened fire. The right-hand Judy’s rear-gunner shot back, but Vraciu had six machine guns in his wings. It was too much for that Judy. It belched a puff of smoke, which turned into a stream of black smoke, and the dive bomber crashed into the sea, its gunner still firing.

Vraciu wasted no time. He fired short bursts into the other Judy, and it fell out of control and into the ocean. Three kills in three minutes, and Vraciu was not done. He saw a fourth Judy pull out of formation, and from astern Vraciu fired a long burst. The Judy erupted in flames and plummeted out of the sky.

Vraciu saw three Judys approaching their pushover points for dive bombing, and he crept up on the rear Judy. When he came in range, he squeezed the trigger, and the .50-caliber bullets disintegrated the target.

Now Vraciu headed for the leading plane of the trio and fired on it. The Judy vanished in a bright explosion, apparently caused by its bomb cooking off. “I had seen planes blow up before but never like this! I yanked the stick up sharply to avoid the scattered pieces and flying hot stuff, then radioed, ‘Splash number six!’” he said later.

Vraciu looked around and saw no enemy planes nearby, so he headed back to Lexington for fuel and ammo. As he taxied up the deck, Vraciu looked up at the flag bridge, where Mitscher himself was looking down at him. Vraciu climbed out of his cockpit, grinning, and held up six fingers for his kills, accomplished with a mere 360 rounds of ammunition. After the plane was parked, a group of well-wishers, headed by Mitscher himself, greeted the aviator, and the admiral asked for a photograph for his own file. Vraciu now had 18 kills, and gained one more the next day. The steely pilot and genial shipmate would survive the war to receive a Navy Cross for his valor. As for the photo, the war correspondent who took it did not keep it to himself. It made American newspapers as a symbol of victory.

Lexington’s aviators claimed four Jills, nine Judys, two Kates, and seven Zeros without loss. Bunker Hill’s VF-8 fighters were less impressive, with only four Zeros and a Judy, but Bataan’s VF-50 punched out five Zeros, four Judys, and a Jill. One American observed that the action had reminded him of an old fashioned turkey shoot back home. The aerial aspect of the unfolding Battle of the Philippine Sea then came to be known as the “Great Marianas Turkey Shoot.”

Meanwhile, Zenji Abe, the canny Pearl Harbor veteran, kept on course as Japanese planes exploded or crashed about him, arriving over the American fleet at 13,000 feet. Even though his wingmen were gone and Hellcats were behind and above him, Abe lowered his nose for a proper dive-bombing attack on Wasp. The bomb missed but detonated near the ship, injuring two men and doing light damage. Abe pulled out and miraculously survived American flak and fighters, the only Japanese pilot to drop a bomb on an American carrier that day and return home safely.

Two more Judy dive bombers headed for Wasp and swung around her stern. The carrier’s lookouts thought they were “friendly” until both planes went into their bomb runs. All of the carrier’s antiaircraft guns opened fire, but one plane was able to drop its bomb, which landed just off Wasp’s port beam, spreading shrapnel which killed one man and wounded several others. Wasp gunners took their revenge with a stream of fire that sent the Judy smoking into the sea, 12,000 yards ahead of the carrier.

Four Japanese torpedo planes made runs on Enterprise and Princeton. Flak took them down. A lieutenant on one carrier’s bridge wrote, “On at least one occasion, so many Japanese planes were being shot down—great balls of fire, which, in spite of intense sunlight showed brilliantly red against the sky, or long plummets of black smoke plunging into the sea—that it was impossible to make an accurate count of them. For minutes on end, there were beautiful vapor streams forming crisscrossing white arcs against the azure sky as planes dived and climbed.”

VF-1 from Yorktown, under Commander “Smoke” Strean, tore into the Japanese with energy, diving from 24,000 feet, leading 10 Hellcats. In a furious and confused battle, they sent Zeros smashing into the water, accounting for 34 fighters and three bombers in the day. Lieutenant R.H. Shireman, Jr., led his division down from 20,000 feet into a giant dogfight 10,000 feet below. He battered a Zero in a stern run, then zoomed past it, but the Zero was in an inverted spin and splashed into the sea. Lieutenant (j.g.) G.W. Staehli saw a Judy diving at 5,000 feet. He shot at its cowling. The Japanese plane rolled over on its back, finished.

Incredibly, some Japanese bombers besides Abe were able to penetrate the American defenses, ganging up on the destroyer Stockham, the picket ship. For 20 minutes, Japanese planes swooped in on her from every direction, but incredibly they scored no hits, as most of them were shot down by American flak and fighters.

Lieutenant William Lamb of Princeton’s VF-27 found himself amid 12 Jill bombers over Stockham with only one of his six guns working. He simply stayed out of their range of fire and called in additional American fighters. As they appeared, he plowed into the Jills and shot down three of them with his one gun.

Now the veterans of Enterprise’s VF-10, the “Grim Reapers,” finally got a chance to add to their carrier’s long and illustrious record in the defense of Stockham. Two Enterprise pilots, Lieutenant Donald Gordon and Lt. (j.g.) Richard W. Mason, caught a Judy pushing over into its dive on a battleship and charged in, setting it on fire.

Lieutenant Marion O. Marks and Ensign Charles D. Farmer saw two Jills setting up torpedo runs against the battleships. Marks shot up one Jill, preventing it from launching its torpedo, but not splashing it. Farmer, however, fired two long bursts from astern, and the Jill suffered a violent explosion.

The battleships endured a lot of attention, but little damage. Once again torpedo bombers attacked South Dakota, but Bob Feller and his shipmates on Alabama drove them off. A Judy took advantage of this distraction to attack Alabama but missed. Indiana shot down five enemy planes. One torpedo launched at Indiana exploded only 50 yards from her. Another Jill flew toward Indiana at 12:14 PM but lacked a torpedo. The Jill slammed into Indiana’s starboard side, bounced off the waterline, and immediately sank, doing very little damage. Another Jill fired a torpedo at the battleship Iowa, but missed.

On the nearby heavy cruiser San Francisco, the ship’s automatic weapons officer took a superficial wound on a finger, probably from friendly fire. To encourage his gun crews, he yelled, “The bastards have drawn blood, shoot them down!”

Now, the surviving Japanese planes were past the battleships and nearing the carriers. A Judy and three Jills attacked Enterprise and the light carrier Princeton. The Judy attacked Enterprise in a shallow dive, but the carrier and her numerous escorts opened fire. The Judy could not drop her bomb, instead wobbling off and crashing. A Jill tried to torpedo Princeton but was shot down by the ship’s guns. The carrier and her screen took care of the second Jill, and the third dropped its torpedo toward Enterprise just before the carrier’s five-inch gun took out its right wing. The Jill slammed vertically into the sea 300 yards off Princeton, and the torpedo missed.

At 12:03 pm, Bunker Hill lookouts spotted two Judys jumping out of a cloud four miles away at 12,000 feet. The ship’s guns treated the incoming dive bombers to a wall of shells as the planes hurtled toward the smaller Cabot. A direct hit tore a Judy in half, with the front end landing off the Bunker Hill’s starboard bow and its tail off the stern. The other plane dropped its bomb close aboard the carrier’s elevator, shaking Bunker Hill, knocking out the port elevator, setting off fires in two ready rooms, rupturing fuel tanks and vents, killing two and wounding 27 men. But the ship’s damage control crews got straight to work, and the carrier stayed in the battle.

By 12:15 pm, the American radars were clear of Japanese planes, and the survivors—including Zenji Abe—shuffled into formation to head home. There were not many left. Of the 128 planes Ozawa had hurled at the Americans, only 31 (16 Zeroes, 11 Judys, and four Jills) returned. All across the ocean near the American fleet, fires blazed and oil slicks poisoned the water, the wrecks of Japanese aircraft and their hopes for victory.

Worse was to come for Ozawa. His carriers steamed along, awaiting results. Nobody seemed too concerned aboard Taiho about the damage from Albacore’s hit. She cracked along at 26 knots while poorly-trained damage-control crews tried to repair ruptured fuel and oil lines or pump overboard fuel in damaged tanks. A lot of the unrefined Borneo crude did not make it into the Pacific but sloshed around the carrier’s hangar deck. At this point, as Ed Beach would write caustically later, one of Taiho’s ill-trained damage control officers made a decision that “qualified (him) for the United States Navy Cross,” by starting all blowers and fans and opening all ventilation lines and bulkhead doors to reduce the concentration of fuel vapors and clear the atmosphere.

While this damage control battle raged, another American submarine turned up amid Ozawa’s force to wreak additional havoc, the brand-new Cavalla, under veteran submariner Commander Herman Kossler in his first command. His sub had been patrolling between Guam and Mindanao when it was given orders to head for the sound of the guns on June 14. After coping with a storm that day and making a failed attack on a convoy the following day, Kossler contacted Ozawa’s ships on the 18th at 8:30 pm, but the Japanese ships detected Cavalla, and he had to spend the evening evading them.

At 10:39 am, Cavalla reached the point he had been ordered to assume, and sure enough, he saw four planes circling in the distance through his periscope, then masts, and then screws on the sonar. Beyond that was a carrier. “The picture was too good to be true!” he later wrote.

Shokaku was steaming at 25 knots, making a large bow wave. Peering through his periscope, Kossler saw that Shokaku’s forward flight deck was crowded with planes. With his executive officer and torpedo officer, Kossler identified his target and set up the shot: angle on the bow, starboard 40, all tubes ready.

Kossler took one more look through the periscope and saw that the enemy destroyer was suddenly headed right for Cavalla, 100 yards off. Kossler wasted no time, firing five torpedoes at Shokaku, then diving down before launching the sixth.

The torpedo streaks attracted the veteran Japanese destroyer Urakaze, which sprinted in. “Rig for depth charge!” Kossler shouted. But before a single depth charge fell, the crew heard the solid sound of three violent metal-crushing explosions against Shokaku’s hull—direct hits on the carrier.

Cavalla dived to 150 feet with hard left rudder. As it did, the first four of 106 Urakaze depth charges exploded near the submarine. For three hours, Kossler’s boat absorbed a pounding.

As Cavalla was brand-new, she had not proven herself depth-charge-proof and suffered a number of leaks. Sea water poured into the motor-room bilge at high speed. Then came a hissing sound above the galley, and Cavalla began to sink deeper. Kossler ordered main induction drains opened to test them, and sea water spurted out of them, forcing Kossler to run his sub up angle in order to maintain her depth.

After three hours, Urakaze gave up, and Cavalla headed off, still able to fight.

Above, however, chaos reigned. Shokaku actually took four torpedo hits at 12:20 PM, and the carrier slowed and fell out of formation as fire and explosions tore her apart. The veteran crew did its best at damage control, but could not contain fire and fumes from leaking gas and oil tanks, and her bow settled into the ocean. Seawater poured through her open forward elevator. Just after 3 PM, the fires cooked off a magazine, which in turn exploded the Borneo crude oil, ripping Shokaku apart. She sank, taking with her 1,263 officers and men out of 2,000 crew, and nine aircraft.

Nearby, Cavalla’s crew heard and felt the massive explosions and breaking-up sounds as Shokaku sank. Kossler radioed to his boss in Hawaii, Vice Admiral Charles Lockwood: “Believe that baby sank.” Lockwood radioed back: “Beautiful work, Cavalla. One carrier down, eight more to go.”

For the feat, Cavalla would receive a Presidential Unit Citation, survive the war, and ultimately be turned into a museum in Texas in 1971.

Lockwood’s point, though, was quite correct: there were eight more Japanese carriers to go on June 19, 1944. Despite suffering horrendous losses so far—one carrier sunk, one gravely damaged, hundreds of planes lost—Ozawa was not done yet. Worse still, while Spruance had absorbed these two blows and was ready to endure more, he had not unleashed his powerful offensive arm against Ozawa.

The Battle of the Philippine Sea was becoming a bloody struggle, and more rounds awaited. The “decisive battle” was, indeed, quite undecided.

Author David Lippman resides in New Jersey and writes frequently on a variety of topics for WWII History. The is the first of a two-part article on the Battle of the Philippine Sea. Part two will appear in the June issue.