By Mark Carlson

For thousands of Allied airmen the most terrifying sight they ever beheld was a Mitsubishi A6M Zero bearing down on them—burnished black cowling over a snarling Sakae engine, staccato bursts flashing from two machine guns and two cannon—often the last thing they ever saw.

No fighter in history has been the subject of more debate than the Zero. When it first took undisputed command of the Pacific skies in 1941 it gained a reputation for being the best and most dangerous enemy plane in the world.

For the first two years of the war, the British, Dutch, French, Chinese and American fighters that faced the Zero were woefully inadequate in the draconian new world of high-speed aerial combat. The Zero reigned supreme until the Arsenal of Democracy was ready to put its newest fighters into front-line service. Then, with the downing of one plane in June of 1942, the slow but inevitable fall from glory for the legendary Zero began.

Preceding the Zero was the Mitsubishi A5M Type 96, code-named the “Claude” by the U.S., the first all-metal monoplane carrier-based fighter in the world. The Claude was reasonably successful during the Second Sino-Japanese War against Chinese fighters, most of which were obsolete by 1937, and set the standard for what Japanese Navy pilots sought for the next generation super fighter.

However, what the Claude had achieved over Nanking and Manchuria was deceiving. The Boeing P-26 Peashooter and Curtiss F11C Goshawk fighters they faced were hardly a challenge for the highly skilled and motivated Japanese pilots. Here the Samurai ethos played a significant role in the birth of the Zero. Japanese fighter pilots were modern-day aerial warriors more focused on duty and honor than in survival. They wanted a swift and light fighter, a modern aerial equivalent to the Katana sword carried by the medieval Samurai. The Imperial Japanese Navy Air Force’s (IJNAF) specifications for the new fighter called for high speed, high rate of climb, long range, high maneuverability, machine guns and cannon—with the ability to land on and take off from carriers. In order to expedite development, only existing engines or ones already on the drawing board were to be used for the new plane.

The 800 horsepower generated by the Nakajima Kotobuki nine-cylinder radial engine used in the Claude was sufficient for 1937, but was far below what was already in service around the world. Almost from the outset the Zero’s design was the result of a series of compromises dictated by its perceived mission and what the pilots wanted. In the Imperial Japanese Navy, test pilots at the main IJNAF base at Yokosuka had more to say about what they expected of a proposed design than their western counterparts. Consequently, when Mitsubishi submitted its proposal for the new fighter in 1939 they gave the pilots what they wanted. As Chief Designer Jiro Horikoshi wrote later, “Instead of pondering the future of the aircraft, our immediate goal was to win the contract.”

There was no mention of armor protection, which was anathema to a Samurai. Therefore what the new fighter gained in performance it sacrificed in structural strength and safety. Again the Japanese cultural mindset played a role. A pilot was expendable as long as he did his sacred duty for the Emperor. Armor protection and self-sealing fuel tanks were left out in favor of lighter weight and greater range. The Japanese Air Ministry bowed to the wishes of the pilots, whereupon Horikoshi and his team began work on the new super fighter. To save on weight, Horikoshi’s design utilized advanced light aluminum alloys. The huge wing, unlike nearly all American and British designs, was integral to the fuselage. Large ailerons, rudder and elevators gave the Zero unprecedented maneuverability. Interestingly, Allied air forces were learning that maneuverability was the least important criteria for a fighter. The powerful pursuit planes being developed in the United States and Great Britain were faster, more powerful, better armed and more heavily armored.

The new plane gained considerably more power with the Nakajima 950-horsepower Sakae 14-cylinder radial, without a drastic increase in weight, again a design compromise. But it wasn’t the quantum leap forward that most new designs demanded. To illustrate, consider that the U.S. Navy’s obsolete Grumman F3F, the last biplane in the inventory, was powered by a Wright R-1820 with the same rated power. Of course, the Zero would have torn the F3F apart with ease.

Again following the Samurai philosophy, the plane was more a close-in sword than a flying machine-gun platform as in the West. In combat a machine gun will always beat a sword. Still, a sword in the hands of a master can be deadly as the world would soon learn. The new fighter was designated the Type 0 Rei-sen. “Zero” is a loose translation of the name.

Saburo Sakai, the highest-scoring ace to survive the war, thought the new plane was a wonder. “It excited me as nothing else had ever done. Even on the ground it had the cleanest lines I had ever seen in an airplane,” Sakai said. “It was a dream to fly, and even light finger pressure brought instant response. We could hardly wait to meet enemy planes in this new aircraft.”

The IJNAF pulled a cloak of secrecy over their new project, so as far as the West was concerned, in any future air war, they were likely to face only the Claude and other familiar Japanese aircraft. The illusion was shattered with the first appearance of the Zero in 1941. The new fighter was a shock to Allied naval and army air forces. In contrast to the Claude, the Zero was swift and dangerous, tearing through less maneuverable American, French, Chinese and British formations. The legend of the Zero had a psychological impact that is hard to imagine today. Nearly every Allied fighter was judged by how it might perform against the Zero.

It should be remembered that fighter pilots all over the world tended to overstate the abilities of their foes in order to make their own losses tolerable and increase the glory of victory.

The Zero enjoyed numerical and psychological superiority in the months after Pearl Harbor. From 1940 to 1945 nearly 11,000 Zeros were produced in five major variants. It was the core of the IJNAF as well as several units of the Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF). Its long range and low landing speed made it perfect for Pacific carrier operations.

Because of its clean design, excellent stability and low wing loading the A6M could be considered the best fighter in the war. At low speed it could turn inside any Allied fighter in service until 1943. Yet there were some quirks. The torque of the three-bladed propeller and high-power-to-weight ratio meant the Zero could snap-roll to port in the blink of an eye, but a turn to starboard took longer and required more effort. Zero pilots learned to use the left rolling turn as a way to get inside the turn of an enemy fighter and to evade a pursuing one.

For the first year of the war Allied pilots—if they survived the encounter—were amazed at what the new Japanese fighter could do and the legend quickly grew. Joe Foss, the Marine ace of the famous Cactus Air Force on Guadalcanal had told his pilots, with grim tongue-in-cheek humor, “If you find yourself alone and see a Zero at the same altitude as you, consider yourself outnumbered and go home. They were not a plane to tangle with unless you had an advantage.”

From December 1941 until the fall of 1942, Zeros shredded the air forces defending the Philippines, the Dutch East Indies, Malaya and Singapore. No Allied fighter could stand up against the Zero in a dogfight, not even the superb Supermarine Spitfire. The Allied air forces had all made one crucial mistake. They fought the new Japanese plane on its own terms, in its own performance envelope. In retrospect, they cannot be blamed for this. The learning curve against such an adversary was extremely steep. Those who survived and those in a position to be objective found that the Zero was not perfect. It could be defeated.

Slowly the Allies began to test different tactics against the Zero. Its light weight was actually a liability as Japanese pilots soon found out over China and the South Pacific. If an Allied fighter gained an early advantage in altitude, as demonstrated by the Flying Tigers, they could dive into and attack a Japanese force with little danger of being pulled into the dogfight.

The Zero was also vulnerable to the heavy machine guns carried by American fighters, as well as effective anti-aircraft artillery.

But what ultimately led to the demise of the Zero’s myth of invincibility was chance—and perhaps human nature.

As the two mighty fleets of the U.S. and Japan began their legendary duel to the death at Midway on June 4, 1942, two small Japanese aircraft carriers attacked the U.S. naval base at Dutch Harbor in the Aleutian Island chain. The Junyo and Ryujo launched 20 Vals to bomb hangars, oil tanks, warehouses and a freighter, while 11 Zeros ran strafing runs. One three-plane element was under the command of Chief Petty Officer Makoto Endo. He and the other two pilots, Flight Officers Tsuguo Shukada and Tadayoshu Koga made an attack on a PBY Catalina in the harbor and strafed its crew as they tried to paddle away in a life raft. Then, during another run over the island, ground fire hit Koga’s Zero.

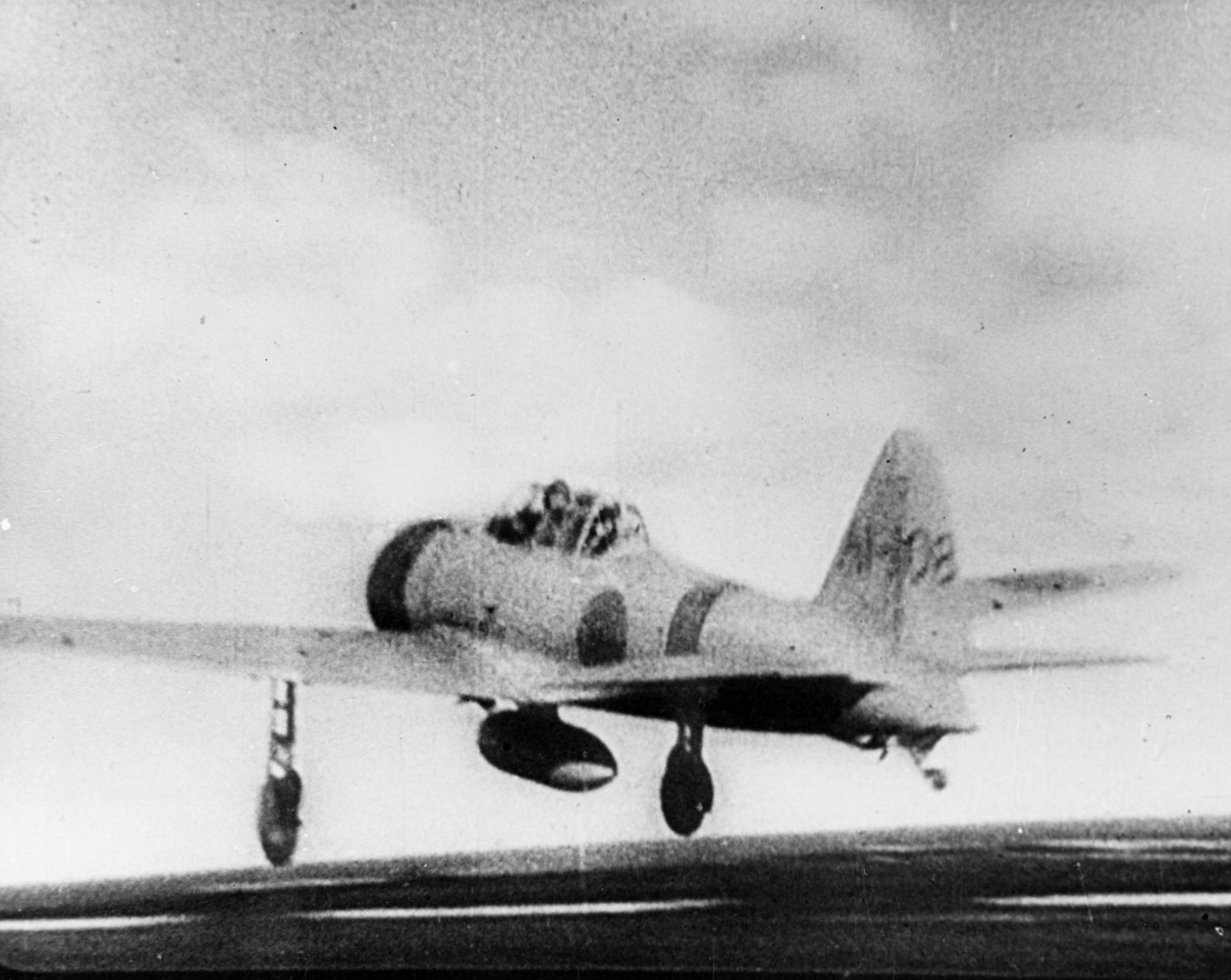

Banking away, the 19-year old pilot made his way to a small island designated for emergency landings. A submarine was on hand to recover any downed airmen. But he had 25 miles to go and an American bullet had severed the oil line between the engine and oil cooler. With every passing mile, the precious fluid sprayed out into the cold slipstream of the Aleutian sky. The A6M, number 4593 had only been in service for three months after rolling out of Mitsubishi’s Nagoya factory in February. The regulation light gray paint and bright red “Hinomaru” emblem were being spattered with oil as Koga lowered his wheels over Akutan Island. His comrades watched as he lined up on a flat patch of grassy ground and touched down. But the wheels dug into what turned out to be tall grass under two feet of water. The Zero slammed to a stop as the propeller dug into the soft tundra and flipped onto its back. Endo and Shukada circled to see if their friend got out. They couldn’t know that Koga had been killed in the impact. Under orders to destroy any downed Zeros, they were unable to bring themselves to fire on Koga’s plane and flew back to the Ryujo.

On July 10, a PBY returning from a patrol flew over Akutan Island and a gunner spotted the red “Meatballs” on the Zero’s wings and told the pilot. After a few passes they were certain that a Japanese plane was lying in the marsh. The PBY’s pilot, Navy Lieutenant Bill Thies and his co-pilot, Ensign Bob Larson led their crew on foot to examine the strange plane. What they found was a nearly intact Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero with a dead pilot in the cockpit. Though excited, the men had no idea of the magnitude of the intelligence bonanza their find was for the Allies.

Before the plane was hauled to the beach and crated for shipment, Koga was buried on the island. His plane soon arrived at Naval Air Station San Diego on Coronado. There, under heavy security it was studied and repaired. Bearing U.S. Navy markings it was test flown by Lt. Com. Edward Sanders over the ocean off the California coast from September 20 to October 15, 1942. What Sanders and other pilots learned would be a major factor in winning the Pacific air war.

While the Zero proved to have amazing stability and agility, it did have some remarkably vulnerable handling characteristics. For one thing, it took a lot of effort to make a roll to the right. Also, while it was able to turn on a dime at low speeds, its large wings and ailerons tended to lock up at speeds above 200 knots. Another flaw was the float-type carburetor, which cut off fuel when the Zero went into a steep dive. These defects were made known to the navy and army air forces in the Pacific.

The examination of Koga’s Zero was a coup for the Allies. What was learned helped American fighter pilots fight the Zero on nearly equal terms. However, the story that the Grumman F6F Hellcat was designed and built based on what the navy learned from test-flying the A6M is not true. The Hellcat was already in prototype form in the summer of 1942. But what Koga’s Zero taught the navy was incorporated into the training of new Hellcat pilots. In addition, a careful examination of the Zero’s structure showed that its light weight and lack of armor and self-sealing fuel tanks was also a serious liability. American fighters utilized greater power, climb rate and excellent high-altitude performance, and these factors would prove to be the Zero’s undoing.

The superb new planes rolling out of the factories of Grumman, Vought, North American, Martin, Douglas and other manufacturers incorporated the best materials, aeronautical engineering knowledge and ingenuity in the world. What the Japanese Zero pilots faced in the skies over the western Pacific after the spring of 1943 could no longer be overcome. The aegis of the Zero was over.

However, no matter how good a plane is, the outcome of any aerial engagement usually comes down to the skill of the pilot.

Saburo Sakai, in his book Samurai! cites an event in June 1944 near Iwo Jima in which he dueled 15 Grumman F6Fs in a running air battle that lasted for nearly half an hour. The Japanese ace shot down two Hellcats, and though the Americans made repeated runs at Sakai and literally filled the sky with hot lead and steel, they failed to bring him down. His experience with the nimble Zero was the key factor to survival that day. When he landed on Iwo Jima, there was not a single bullet hole in it.

Of the nearly 11,000 A6Ms built during the war, only 16 still exist in museums and private collections. Ironically, the only two flyable Zeros are in the United States. One is owned by Planes of Fame Air Museum in Chino, California, while the other is in the collection of the Commemorative Air Force in Midland, Texas.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments