By Alex Zakrzewski

In the late afternoon of September 1, 1939, the 18th Uhlan Regiment of the Pomorska Cavalry Brigade was holding its position along Poland’s heavily forested northwest frontier when orders arrived to attack the flank of the advancing German 20th Motorized Infantry Division. Wasting no time, the regimental commander, Colonel Kazimierz Mastalerz, ordered his depleted squadrons to mount and set off to fulfill his mission. At around 7 pm, scouts spotted a column of German infantry badly exposed in a forest clearing, perfect prey for a saber charge. When the regimental adjutant suggested attacking dismounted, the colonel would hear none of it.

“Young man,” Mastalerz said tersely, “I am quite aware of what it is like to carry out an impossible order.” Spurring their horses forward, the Poles burst out of the woods with sabers drawn and quickly scattered the enemy infantry. There was no time to celebrate, however, for hardly had their horses caught their breath before a troop of German armored cars arrived on the scene and opened a devastating hail of fire from their machine guns and automatic cannons. Twenty troopers, including Mastalerz, were killed before the horsemen could turn their mounts and flee behind a nearby hillock. The next day, Italian war correspondents were brought to the scene and told that the Polish cavalry had charged German tanks.

Lance-Wielding Anachronism?

It was in this way that arguably the most enduring myth of World War II was born. To this day, the notion that Polish cavalry charged German armored vehicles with Quixote-like naivete continues to be cited as historical fact, even among academics. In truth, while Polish strategists in 1939 may have overestimated the value of their cavalry, they duly recognized its growing obsolescence in modern warfare and sought to adjust its tactics and armaments accordingly. Contrary to popular belief, the Polish cavalryman at the dawn of World War II was not the lance-wielding anachronism depicted in German propaganda, but a well-trained and highly motivated elite mobile infantryman. An examination of the cavalry’s combat record during the 1939 invasion of Poland, also known as the September Campaign, proves that, when deployed correctly and properly supported, the Polish horseman was still a force to be reckoned with, even in the face of insurmountable odds.

From King John Sobieski’s legendary Winged Hussars to the famed Polish Lancers of Napoleon’s Imperial Guard, cavalry has always played a defining role in the annals of Polish military history, not least of which was the repulsion of the Bolshevik invaders during the Russo-Polish War of 1919-1921. In that conflict, both sides relied almost exclusively on cavalry for reconnaissance, maneuverability, and transportation. Though armored vehicles were employed, frequent breakdowns and a lack of petrol limited their effectiveness. Instead it was the cavalry that proved to be the deciding factor in many of the war’s most decisive and celebrated engagements. In great clashes like the Battle of Komarow in 1920, widely cited as the greatest cavalry battle since the Napoleonic Wars, Polish Uhlans and Soviet Cossacks dueled with sword and lance while bombs, bullets, and planes whizzed overhead. In the end, Marshal Semyon Budyonny’s 1st Soviet Cavalry Army proved no match for the élan of the Polish horsemen, who were largely credited in the popular imagination of a grateful nation with having restored Poland to the map of Europe.

A Natural Source of Mobility

Hence, while the cavalry finished the war wreathed in laurels, the armored units had earned in the minds of many Polish officers a lasting reputation for unreliability. During the interwar years, as these officers rose to the Army’s top ranks, many continued to cling to a misguided confidence in the continued value of horse and rider. In the war against the Bolsheviks, ingenuity and improvisation had allowed the cavalry to play a crucial role in conjunction with modern technology. Why would the same not be true for coming wars? They further pointed to the fact that along the Eastern borderlands, where communication was severely hampered by dense forest and vast wetlands, the cavalry was virtually the only way to maintain order and patrol against the ever-present threat of a Soviet invasion. Also worth considering was the influence of the aging Marshal Jozef Pilsudski, Poland’s de facto dictator and the “founder and father of the Polish Army.” Concerted reform was impossible without his consent, which became more difficult to ascertain as his health declined and he withdrew from public life.

Moreover, for a desperately poor country with a weak industrial base and shoddy rail and road network, Poland’s four million horses proved a realistic way to provide the army with mobility. Although Poland devoted almost one third of its gross national product to the military, defense spending during the years 1935 to 1939 amounted to just one-thirtieth that of Germany’s. As late as 1937, there were only 6,000 trucks in the whole of Poland that the army could draw on for transportation. As a result, the cash-strapped military was forced to adopt what one Polish historian has bluntly described as a “Doctrine of Poverty,” meaning it was constantly forced to look for ways to improvise modern methods with outdated means. The reliance on the cavalry to fulfill the role of modern mechanized units is the exemplification of this “doctrine.” In his memoirs, Lt. Col. Klemens Rudnicki, who commanded the 9th Lancers in 1939 and would go on to command the 1st Polish Armored Division in the West, wrote, “The material and industrial possibilities in Poland precluded any hope for a rapid change in armament.”

That is not to say that the Polish Army and its cavalry arm remained totally unchanged between the Russo-Polish War and World War II. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, a slew of new tactical directives, coupled with profound changes in weaponry, transformed the cavalry into a highly versatile mobile infantry that shirked swashbuckling charges in favor of dismounted engagement. Indeed, Mastalerz’s charge at Krojanty was the exception rather than the rule as 90 percent of cavalry actions during the September Campaign were fought on foot. During this time the lance, long out of use except on parade and training grounds, was officially dropped as a weapon, and in 1933 the cavalry began receiving specific instruction in antitank defense.

An Eclectic Blend of Old and New Tradition

Reforms were accelerated following Pilsudski’s death in 1935, by which point both the German and Soviet armies were mechanizing at a pace Poland could not hope to match. A specially formed commission determined that the country’s armed forces were at a World War I military level and recommended, among other measures, the mechanization of four cavalry brigades by 1942. In the meantime, a 1937 “Directive on Combat between Cavalry and Armored Units” was issued to further instruct the cavalry on the doctrines of antitank defense. The directive discussed using rough terrain to set up ambushes and the use of modern tank-destroying methods such as antitank guns, antitank ammunition for rifles, and machine guns and artillery support. Although the Poles clearly recognized that tanks were a permanent fixture on modern battlefields, like many Western strategists they believed that armored units would primarily serve an infantry support role and badly underestimated their speed, strength, and maneuverability. This underestimation showed during a 1937 field exercise involving the Nowogrodzka Cavalry Brigade. Its commanding officer, Brig. Gen. Władysław Anders, future commander of the Polish II Corps in Italy, noted his horsemen’s unpreparedness when confronted by tanks. His concerns would prove fully justified in the coming campaign.

The result of these reforms was that by 1939 the Polish cavalry was an eclectic blend of old and new tradition, tactics, and armament. Its 11 brigades totaling 70,000 men, constituted 10 percent of the army’s total strength and were considered to be the elite of the Polish interwar military. Each brigade, the strongest of which numbered just over 7,000 men, contained three to four regiments that were each further divided into four squadrons. Although by the start of the war only one brigade had been fully mechanized, the remaining 10 were each assigned a squadron of 13 TKS Tankettes and seven Model 1934 armored cars, both armed with machine guns. Each brigade also received a complement of up to 78 “Ur” Model 7.92mm antitank rifles and 18 antitank guns, the best of which were the Bofors 37mm. The former was a close-kept national secret that fired an innovative tungsten-carbide-cored bullet capable of penetrating most armor at a distance of 250 meters. The latter was one of the best antitank guns of its size and capable of knocking out any German tank during the September Campaign. Each brigade also boasted a horse artillery troop armed with up to 16 75mm field guns. These guns were generally old, rechambered Russian pieces that proved surprisingly effective against tanks, mainly due to the superior quality of their crews.

Mounts Reduced to Saddled Skeletons

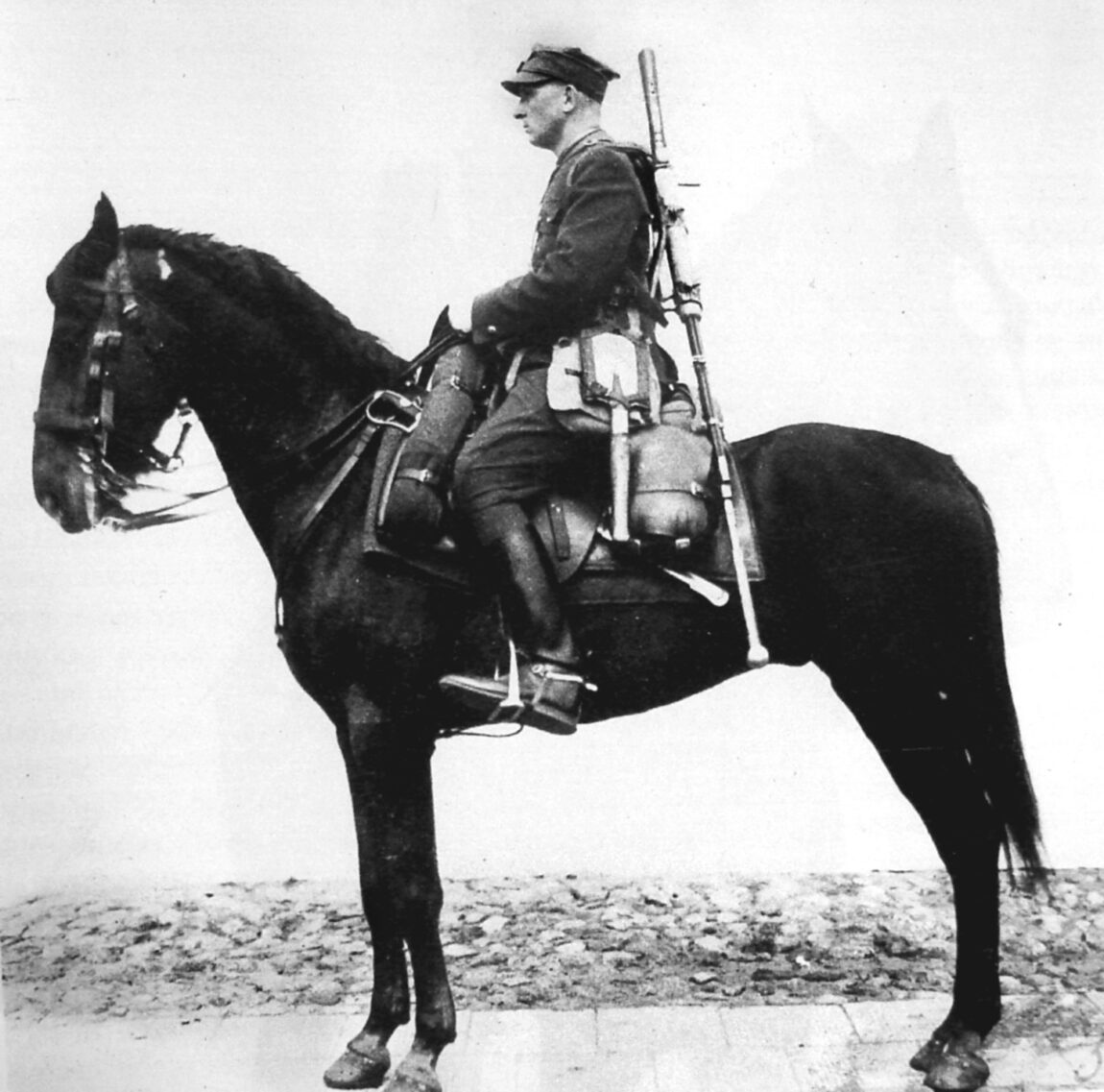

Each cavalry trooper rode into battle armed with a heavy array of equipment that included a saber, M1929 Mauser carbine, bayonet, gas mask, ammunition belt, feedbag, and entrenching tool. On paper, a cavalry brigade possessed the same firepower as an infantry battalion. In practice, however, the cavalry’s firepower was less due to many men being withdrawn from the firing line to serve as horse handlers. All regiments took immense pride in the quality of their mounts and their constant upkeep was the main reason why the cavalry arm absorbed almost 60 percent of the national defense budget (much to the resentment of the military’s other branches). Although the horses were very well trained, the demands of the September Campaign would critically expose how out of place they were on a modern battlefield. While a horse may not require petrol or mechanical upkeep, it does need to be fed, watered, groomed, shod, rested, and treated when sick or wounded. A horse scares in combat, cannot be repaired or cannibalized for spare parts when destroyed, and is particularly vulnerable to air attack. During the campaign’s final days, Rudnicki lamented how his regiment’s mounts had been reduced to “saddled skeletons” that when killed were quickly hacked apart for meat by the starving Polish populace.

The Polish high command envisioned its cavalry acting as a mobile strike force that could be used to exploit gaps in the enemy line, determine enemy positions, and set up ambushes and flanking attacks. Yet, paradoxically, when the war began the cavalry found itself placed in a static defensive position in the initial line of defense where it had little room or time to maneuver. This was because Polish defensive strategy, codenamed Plan Z, called for the bulk of its forces to meet the German attack head on at the frontier. The Poles had no illusions about being able to stave off an invasion for very long and instead hoped to buy as much time as they could until the French and British could mount an invasion of Germany from the West. At the same time, however, they were determined to surrender as little of their new republic’s hard-won territory as possible, particularly from the industrialized Silesian regions in the southwest. As the Germans pressed harder, the Poles hoped to withdraw in good order toward the center of the country where the Vistula River and its tributaries offered natural defense barriers. Polish interwar intelligence was very good (Polish cryptologists broke the German Enigma codes in the early 1930s) and Plan Z correctly estimated that the main German drive would come from the southwest. What they badly miscalculated was the speed and the strength of the German blitzkrieg, the devastation wrought by the Luftwaffe, and the willingness of their allies to come to Poland’s aid.

Fighting Begins Along the Polish Corridor

Although at the dawn of World War II the Polish cavalry was one of the largest in the world and certainly the last to constitute an independent military arm, it should be noted that virtually every other combatant country entered the war with a cavalry force of its own. Germany, perhaps the country most associated with mechanization during this period, actually expanded its use of cavalry during the conflict and, at the start of 1945, had three active cavalry corps in the field. The Soviet cavalry made up a crucial component of Stalin’s forces right up until the fall of Berlin, and by war’s end it boasted 100,000 men on horseback. Nor were prewar foreign observers universally critical of the Polish cavalry—indeed, many shared the Poles’ continued confidence. Shortly before the war, U.S. Ambassador to Poland Joseph Drexel Biddle wrote to U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt that having seen how the Polish countryside becomes a morass in the seasonal rains, he could “more readily understand why the Polish military authorities have maintained an exceptionally large cavalry establishment.” One British military adviser went so far as to openly praise the Polish cavalry to the Daily Telegraph, on the delusional basis that armored vehicles, unlike cavalry, could not fight at night. “The cavalry will raid them, surprise them,” he wrote. “They will destroy them. They will destroy some, and break the morale of the rest.”

In the early morning on September 1, 1939, the aging German battleship Schleswig-Holstein opened fire on Polish positions in the port of Danzig to signal the start of the most technological war yet fought. From the west, south, and north, German troops poured across the Polish border supported by huge quantities of tanks, planes, and automobiles. The British and French had advised the Poles to slow their mobilization plans so as not to antagonize German Führer Adolf Hitler. The result was that at the start of hostilities a large percentage of Polish troops were still in the process of mobilizing and many units were badly understrength. Because the cavalry’s training year ended in September, most of the brigades were fully operational and their presence was immediately felt in the first hours of fighting. South of Danzig, in the so-called Polish Corridor, the action at Krojanty was just one of a series of engagements fought between the Pomorska Brigade and the German 2nd and 20th Motorized Infantry Divisions. So spirited was the cavalry’s defense that by day’s end the 2nd Motorized Infantry Division was forced to notify its corps commander, Generaloberst Heinz Guderian, that it was withdrawing. “I was speechless for a moment,” Guderian wrote in his memoirs. “When I regained the use of my voice, I asked the divisional commander if he had ever heard of Pomeranian grenadiers being broken by hostile cavalry.” The next day he made a point of visiting the division and personally directed the next attack.

Limited Successes for the Campaign

Farther to the south, near the Silesian village of Mokra, the Wolynska Brigade found itself defending a 10-kilometer front against the head-on attack of the 4th Panzer Division. Despite being outnumbered by more than two to one and severely outgunned, the brigade managed to repulse repeated German attacks. The brigade’s commander, Colonel Julian Filipowicz, employed his Bofors guns to such deadly effect that by day’s end the burning steel carcasses of more than 50 enemy armored vehicles littered the field. Surely more would have been destroyed had the brigade not been forced to retreat due to breakthroughs on its flanks. On the night of September 3, Filipowicz achieved another notable success against the German armored columns when he launched a successful raid on the supply lines of the 1st Panzer Division near the village of Kamiensk.

In the north, along the East Prussian frontier, the Polish Mazowiecka Brigade clashed with the German 1st Cavalry Brigade in one of the war’s few cavalry versus cavalry actions. Though most of the fighting was dismounted, there were incidents of Poles and Germans dueling on horseback in the Masurian forests just as they had more than 500 years earlier in the days of the Teutonic Knights. Farther east along the same front, the Podlaska Brigade became the first Allied unit to actually invade Germany when it launched a successful cross-border raid into East Prussia that terrified the local Landwehr, overran a number of bunkers, and netted a sizable amount of prisoners and equipment. Though the brigade was soon forced to retreat back across the border without having achieved any real strategic objective, news of the raid was broadcast across the country and provided a much-needed boost to national morale.

These limited successes, while certainly inspiring, did little to alter the course of the campaign. Within days of the invasion, the entire Polish Army was in full retreat toward Warsaw with the German panzers on its tail and the Luftwaffe wreaking havoc from the air. Still, even in these darkening days, there are numerous examples of the cavalry units displaying incredible professionalism and resolve, despite suffering casualty rates as high in some cases as 60 percent. During the week-long Bzura Offensive, the Wielkopolska and Podolska Brigades led a counterattack against the German 8th Army that managed to divert its drive on Warsaw and recapture a number of key towns and villages. In the south, Major Henryk Dobrzanski of the 110th Uhlans ignored orders to surrender and instead disappeared into the forests around Kielce to wage a successful partisan campaign under the code name Hubal. Anders’ bedraggled horsemen made a point of singing defiantly as they rode their emaciated mounts through throngs of fleeing refugees, and in besieged Warsaw, Rudnicki had to coax some of his officers out of leading suicidal final sorties to preserve the honor of their regiments. “The Polish cavalry attacked heroically; in general the bravery and heroism of the Polish Army merits great respect,” wrote Generalfeldmarschall Gerd von Rundstedt, commander of Army Group South. Generalmajor Kurt Meyer of the Waffen SS agreed, adding, “It would not be fair on our part to deny the bravery of the Polish forces. The battles along the Bzura were fought with great ferocity and courage.”

Not surprisingly, cavalry units fighting near Lublin were among the final Polish troops to surrender on October 6. By this point the Soviets had invaded from the east, Warsaw was in German hands, and Poland had once again vanished from the map of Europe. With it disappeared the timeless tradition of the Polish cavalryman.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments