By Sam McGowan

Since the end of World War II, the aviation press has made the North American P-51 Mustang into the superstar Allied fighter of the war. In reality, however, the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt aircraft was the most widely used U.S.-built fighter, and in many respects it was the most capable. During the last year and a half of the war, P-47s represented nearly half of all U.S. Army fighters in overseas groups.

It was the P-47, along with the longer range Lockheed P-38 Lightning, that gained air superiority for the Allies in the skies over Western Europe. The P-47 was the second most popular fighter in the Pacific Theater, and it was the Thunderbolt that came to personify the fighter-bomber, a concept that still dominates the United States Air Force.

Development of the P-47 Thunderbolt Aircraft

The Thunderbolt was Republic Aircraft’s entry into the 1940 competition for an American-built fighter that would be capable of holding its own against the German fighters that dominated the air war then taking place over Europe. Based in Farmingdale, New York, Republic Aircraft was the successor to the company Russian-born aircraft designer Alexander de Seversky had founded in 1935. Seversky had designed the first modern American fighter, the Seversky P-35, and followed it with the P-43 Lancer, a design that was never purchased by the U.S. Army. In 1939, four years after founding the company, Seversky fell victim to corporate maneuvering when he was voted off the company’s board. He was in Europe at the time, trying to interest the British in his design ideas. The new leaders changed the name of the company to Republic Aircraft.

Republic’s initial venture into the fighter design game was a small, lightweight fighter built around the Allison V-12 engine. Designer Alexander Kartveli, who had worked closely with Seversky on the company’s previous designs, was put in charge of the project. When the Army voiced concern about the demand on the liquid-cooled engines, Republic’s attention turned toward the air-cooled Pratt & Whitney Double Wasp R2800 engine, which produced more than 2,000 horsepower—but which also consumed nearly twice as much fuel as the Allison.

Kartveli “borrowed” from Seversky’s previous radial engine designs and came up with a design that incorporated many of the features of the P-43. The more powerful engine allowed Republic to increase the weight of its fighter design dramatically, making it the heaviest single-seat fighter built up to that time. One of the laws of aircraft performance is that rate of climb is in direct relation to the excess power available at a particular airspeed. The increased weight of the XP-47 gave the airplane a slower rate of climb than was really needed for an interceptor. However, by the time the P-47 entered combat, the necessity for interceptors had begun to decline and the heavy weight of a Thunderbolt aircraft gave the airplane other desirable features, such as increased speed in a dive and resistance to damage from gunfire.

The Thunderbolt is one airplane that truly deserves the often overused adjective “rugged.” The air-cooled engines were less susceptible to engine failure in combat since there was no coolant to be lost to leaks caused by battle damage.

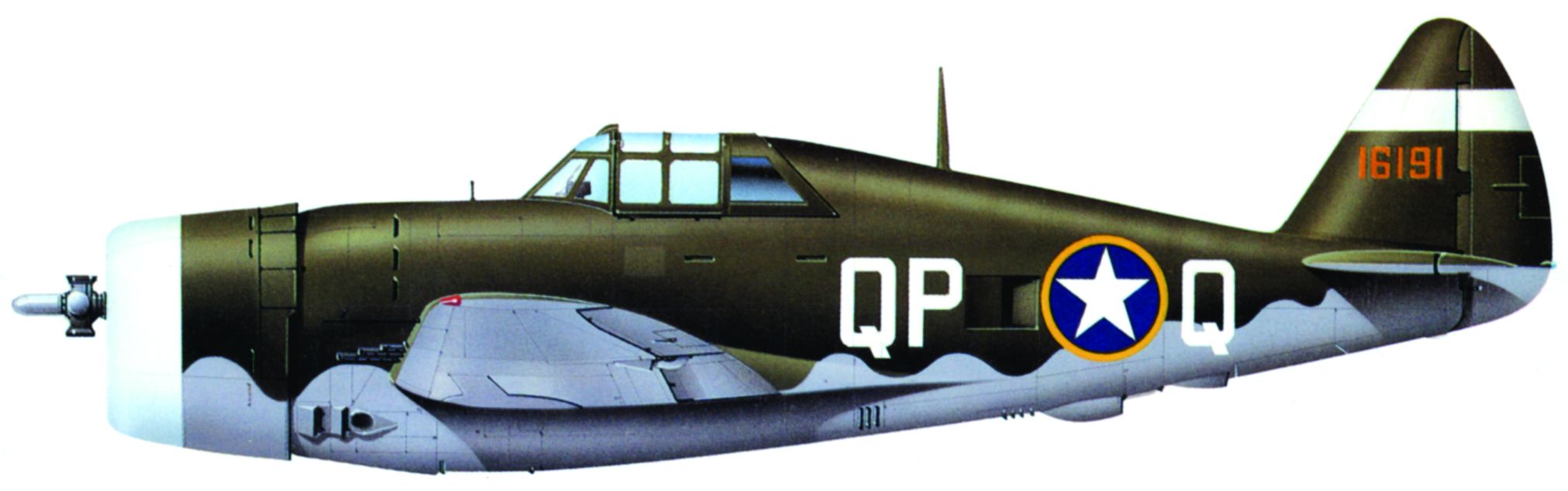

Deploying the Thunderbird Aircraft with the 56th Pursuit in 1942

The first U.S. Army operations group to fly the P-47 was the 56th Pursuit Group, which was conveniently based in the vicinity of the Republic factory at Farmingdale—in fact, one squadron was right there on the field. The others were at Bridgeport, Connecticut, and Bendix, New Jersey. Initially equipped with Bell P-39s and Curtiss P-40s, the 56th began receiving P-47s in the spring of 1942, the initial deliveries nearly coinciding with the assignment of Captain Hubert “Hub” Zemke to the group after he returned from an overseas tour as an observer in Russia. Zemke’s name and the P-47 would become forever linked.

It was not until early 1943, more than a year after the U.S. Army Air Corps entered combat, that the first P-47s arrived overseas. Previously, the burden of fighting the Axis had fallen to the P-39s and P-40s in the Pacific and the P-38, P-40, and British Supermarine Spitfire and Hawker Hurricane in Europe and North Africa. The first American fighters sent to England were Lockheed P-38s, but the war in North Africa sucked them all out of the British Isles, leaving only Spitfires to escort B-17 and B-24 bombers on missions over occupied Europe.

The nimble Spitfire had earned a reputation as an outstanding fighter during the Battle of Britain in 1940, but it lacked the range to go with the bombers on the long raids and was thus ineffective as an escort fighter. In fact, Spitfires were only capable of going a few miles east of the English Channel without extended-range fuel tanks. Even with the tanks, their range was limited. The veteran 56th, which had been re-designated as a fighter group, arrived in England in early 1943 but did not go into combat until April. The VIII Fighter Command decided that the airplane needed modifications—including additional armor—and the pilots needed combat training before they entered the fray.

When the 56th Fighter Group arrived in England, there were already two fighter groups there. The 78th Fighter Group had gone overseas with P-38s, but it lost them and most of its pilots to North Africa—leaving the remaining pilots without airplanes—and began re-equipping with Thunderbolts, as did the 4th Fighter Group. The 4th Fighter Group was made up of American Eagle Squadron pilots who had volunteered to fly with the British Royal Air Force before America entered the war, and to a man they all loved the Spitfire and came to hate the Thunderbolt, almost with a passion. Like their British cousins in the RAF, the young Americans thought the Spitfire was the best fighter ever built, an idea that was more truthful in spirit than in actual merit. They were not happy that they were giving up their light and maneuverable steeds for the heaviest fighter in the world.

A “Jug” and a “Milk Bottle”

The pilots in the 4th Fighter Group started referring derisively to their new birds as “seven-ton milk bottles” in reference to the shape of the fuselage. It was not the P-47’s milk jug shape that gave the airplane its name, however, contrary to the assertions of some writers. Many of the pilots believed they were to be sacrificed and started referring to the P-47 as a “Juggernaut,” a moniker that was naturally shortened to just plain “Jug.”

The first Thunderbolt missions were advanced training flights flown over German-occupied territory as theater orientation for the pilots. Initially, the German fighter pilots paid little attention to the Allied fighter formations. Their interest was in the bombers. It was not until April 15, 1943, that the P-47s had their first encounter with German fighters. Don Blakeslee, a former Eagle Squadron pilot now with the 4th Fighter Group, managed to sneak up on a Focke-Wulfe Fw-190 in a dive and shot it down.

Diving was the P-47’s best asset. The heavier weight and huge, powerful engine allowed the airplane to accelerate rapidly. Nevertheless, Blakeslee’s comments about the airplane were less than enthusiastic. He reportedly said, “It oughta dive, it sure can’t climb.” The mission results were tilted against the Thunderbolts. One was shot down and two others lost to engine failure, a problem that was all too common during early P-47 operations. Thunderbolts were not the only U.S. fighters plagued with engine problems during their introduction to combat. Both the P-38 and P-51 suffered high engine failure rates until problems were identified and rectified.

Getting the P-47 to Berlin

On May 4, 1943, the P-47s were assigned to their first escort mission when 117 Thunderbolts from all three groups were sent to escort B-17s and B-24s attacking Antwerp and Paris. Fighter escort would be the primary mission for the Thunderbolts for the remainder of 1943. Unfortunately, even though the P-47s had a much greater range than the RAF Spitfires and Hurricanes, they still lacked the range to go deep into Germany. The Luftwaffe simply massed its fighter strength inside Germany and waited until the Allied fighter escorts had reached the limit of their range, then struck the bombers. During the summer of 1943, B-17 losses began to mount to the point that the Eighth Air Force temporarily abandoned daylight deep-penetration missions into Germany.

The only immediate solution to the problem was to extend the range of the P-47s, which at the time were the only fighters available, at least until P-38s could be sent to England. Their range was limited by the amount of fuel the airplanes could carry, so the solution was to increase fuel capacity. The use of external tanks, often called drop tanks because they could be jettisoned, was the simplest means of extending the operational range of the fighters. Initial efforts to develop external tanks met with problems. The resin-impregnated, paper tanks leaked and could not transfer fuel at high altitudes because they were not pressurized.

Lieutenant Colonel Cass Hough, the officer in charge of flight testing for VIII Fighter Command, developed a means of pressurizing the tanks using the airplane’s vacuum system. The first tanks carried only 75 gallons, and there was a problem with availability. To alleviate the problem of supply and demand, the VIII Fighter Command adopted British-developed paper tanks that could hold 108 gallons of fuel, which allowed the Thunderbolts to go 325 miles into occupied territory. It still was not enough to take them all the way to Berlin.

One solution for extending the Thunderbolt’s range was to equip the airplane with partially filled unpressurized 200-gallon external drop tanks and use their contents during the climb to altitude. This was an aerodynamically sound practice that allowed the fighters to take advantage of the slower airspeeds—and lessened parasitic drag—in the climb. The procedure allowed the Thunderbolts to arrive at altitude without the drop tanks but with nearly full internal fuel tanks and clean wings, which allowed higher speeds and increased range. This technique initially caught the German fighter pilots by surprise and resulted in some victories for the Thunderbolt aircraft pilots.

Thunderbolt Aircraft in the Pacific

While the 4th, 56th, and 78th Fighter Groups were entering combat with P-47s in Europe, the 348th Fighter Group was on its way to the Southwest Pacific to join the famous Fifth Air Force. Unlike the VIII Fighter Command, which participated in very little combat in 1942, V Fighter Command pilots had been battling the Japanese since early 1942. Some pilots had even been in the Philippines when the war broke out and had been in combat since the beginning.

When the group arrived, Fifth Air Force commander Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney hit on a scheme to build the morale of the new arrivals and to afford the veterans, particularly the P-38 pilots, a measure of respect for the heavy Thunderbolt. He orchestrated a mock dogfight between the 348th commander, Lt. Col. Neel Kearby, and Major Tommy Lynch, who at the time was the highest scoring ace in the Fifth Air Force. The night before the fight, Kenney pulled Kearby aside and told him to lay off the booze and go to bed early, while knowing that Lynch would do just the opposite. The next morning Kearby showed the stuff that would put him among the top-scoring fighter pilots of the war. The P-47 pilots got a boost in morale and the P-38 pilots decided that the new arrivals would be an asset to the New Guinea campaign after all, rather than the liability they had imagined them to be.

Kearby and his pilots adopted tactics that had been used successfully by P-40 pilots against the Japanese, which included attacking in a dive, then breaking away from the enemy formation and refusing to engage the lightweight and highly maneuverable Japanese fighters in a dogfight. Kearby taught his men to use the inertia from their dives to zoom right back up to altitude for another attack. Similar techniques were also adopted in Europe.

The long, overwater legs required for combat in the Pacific dictated the need for increased range, and drop tanks were a high priority. Of all of the American combat units of World War II, the Fifth Air Force was undoubtedly the most innovative, and it had an engineering department at Brisbane that was second to none. There were 110-gallon tanks available that had been initially developed for P-39s and P-40s, but V Fighter Command wanted more capacity. The Fifth Air Force depot went to work on the problem and came up with a 200-gallon, low-profile tank that filled the bill.

What Made the Thunderbolt a Successful Dog Fighter

In spite of their limited range in comparison with the P-38s, the P-47s proved to be a successful fighter in the Pacific. Thunderbolts replaced the P-40 and P-39 in the veteran 35th and 49th Fighter Groups and in one squadron of the 8th Group. Some V Fighter Command pilots were not enthused about the Thunderbolt, but others were. Lt. Col. Neel Kearby was undoubtedly the leading P-47 pilot in the theater and one of the top-scoring aces of the war. Unfortunately, he contracted “Bong fever,” a condition that caused a fighter pilot to become obsessed with catching up and passing the score of the American ace of aces, Major Dick Bong, who had replaced Tommy Lynch at the top of the heap when Lynch was killed in action.

Kearby drove himself to shoot down Japanese planes, as did many other American aces. Although the competition no doubt led to the destruction of countless numbers of Japanese planes, it also caused the young fighter pilots to take dangerous risks, and many lost their lives. Kearby died when he was apparently shot down in a dogfight in May 1944 after he led his wingmen in an attack on a formation of Kawasaki Type 48 bombers. Kearby shot down one, and his wingmen each got another. Then they were jumped by a flight of aggressive Japanese fighters, and Kearby was shot down. He was last seen hanging in his parachute, but he was never heard from again. The wreckage of his airplane was found in March 1946.

P-47s were second only to the Lockheed P-38 Lightning in the Southwest Pacific area of operations. While the longer range of the P-38 made the Lightning the fighter of choice for bomber escort missions deep into Japanese territory, P-47s pulled their share of the load by maintaining combat air patrols over Allied airfields and escorting transports and light and medium bombers on shorter range missions. It was in New Guinea that the Army Air Forces began developing tactics to provide close air support to ground troops, and P-47s were soon adapted to this role as well as air-to-air combat.

Lindberg’s Fuel Management Techniques

The lack of range of the P-47 Thunderbolts was due in large measure to the operating procedures in use in the Army Air Corps. Pilots were taught to operate their airplanes at high RPMs and high manifold pressure and were told that leaning the mixture too much could damage the cylinders. While this was essentially true, most pilots failed to lean as much as they could have and thus consumed fuel at a high rate. In the summer of 1944, the famed aviator Charles Lindbergh visited the Southwest Pacific during a fact-finding tour as a factory representative for United Aircraft, a builder of the Vought F4U Corsair fighter. Previously, Lindbergh had worked as an unpaid consultant with Ford Motor Company, where he became involved with the Thunderbolt, particularly in his research on high-altitude flight.

Lindbergh became intimately acquainted with the P-47 and was shocked beyond belief when he arrived in the Pacific and discovered that the Army pilots were using techniques that led to drastically high fuel consumption. When he returned to New Guinea after a visit with General Kenney in Brisbane, Lindbergh ferried a P-47 back to the forward area. A base operations officer, who was an experienced P-47 pilot, refused to approve his flight plan, which called for a nonstop flight from Brisbane to New Guinea. But Lindbergh knew exactly how much fuel he was going to use and arrived with fuel to spare, a feat that amazed the young Army pilots.

Soon, Lindbergh was teaching his fuel management techniques to P-38 and P-47 pilots and helping increase the effective combat range of V Fighter Command. Lindbergh knew that by reducing propeller RPMs while maintaining manifold pressure, fuel consumption would be reduced and an airplane’s range would be increased considerably.

The P-47 in the Ground Attack Role

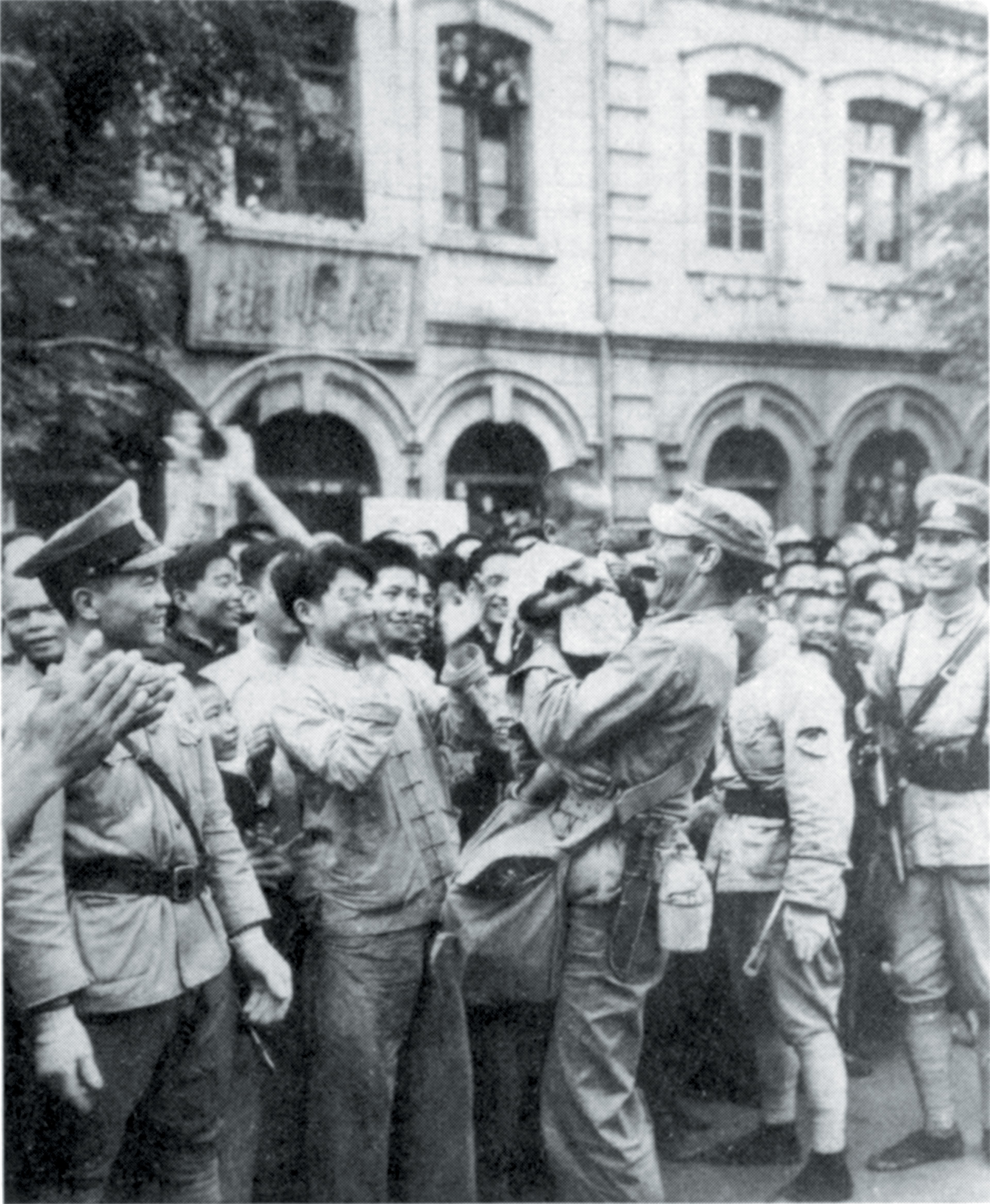

In early 1944, Thunderbolts began appearing in the skies over China. The first P-47 group in the China-Burma-India Theater was the 33rd Fighter Group, a historic group that started out in combat in North Africa flying P-40s, then transferred to the Asian theater after the Sicily campaign. The 33rd was joined by the 81st Fighter Group, which had also entered combat in North Africa with P-39s.

The two groups transferred to the CBI as part of a deployment of several combat groups from the Mediterranean to India to support British Brigadier Orde Wingate’s Chindit expedition into Burma. While the 33rd was equipped with both P-47s and P-38s, the 81st was an all-Thunderbolt outfit from the time the group arrived in India in February. The 80th Fighter Group began combat operations in the CBI with P-40s and P-38s, then equipped with Thunderbolts in the spring of 1944. The 33rd Group flew P-47s only until November 1944, when it became an all-P-38 outfit. The 1st Air Commando Group, a composite unit that was organized in India in early 1944, included two fighter squadrons that started out with an older version of the North American P-51, then transitioned into P-47s later in the year.

Thunderbolts were also active in the Central Pacific. Because of the long distances between land bases in the region, the first P-47s to see duty in the Marianas arrived aboard the escort carriers Manila Bay and Natoma Bay. They were from the 318th Fighter Group, which transferred to Micronesia from Hawaii. Although the convoy, including the two carriers, was attacked by Japanese dive-bombers, all 111 P-47s were delivered to Aslito Airfield on Saipan, where they immediately went into action in support of the ground forces that had invaded the island.

Close air support of ground troops started in the Southwest Pacific in the summer of 1942, when modified Douglas A-20 Havoc light bombers began strafing Japanese positions opposing Australian troops on the Kokoda Track in Papua, New Guinea. General Kenney was so impressed with the tactics that he instructed the fighter groups under his command to develop ground attack tactics as well.

When American forces landed in North Africa in late 1942, Twelfth Air Force commander Lt. Gen. James H. Doolittle restricted the light and medium bombers to medium altitude attack and assigned the close air support role to the fighters because German air opposition was declining. RAF pilots taught the Americans the intricacies of close air support.

The success of the fighter bomber in the Southwest Pacific and North Africa led to the development of ground attack tactics within the fighter commands of all of the numbered air forces—with one exception. Air Corps doctrine called for each numbered air force—which was equivalent to an army—to be multifunctional, with fighter, bomber, and troop carrier commands. The exception was the Eighth Air Force, which had switched from the multifunctional role to a single-purpose command when most of its fighter groups and all of its troop carrier groups were sent to North Africa in 1942. Daylight precision bombing had become the mission of the Eighth, and the role of VIII Fighter Command was to ensure that the bombers got to and from their targets. With no Allied ground troops in occupied Europe, there was no one for whom to provide close air support.

The VIII Fighter Command did, however, begin developing tactics for ground attack against locomotives, airfields, and other targets. The first VIII Fighter Command strafing attack actually came about by accident when a P-47 pilot suffered damage and was forced down to low altitude over France; he strafed a locomotive during the flight back to England. In early 1944, VIII Fighter Command fighters began dropping down on the deck to shoot up Luftwaffe airfields and other targets after their escort missions had been completed.

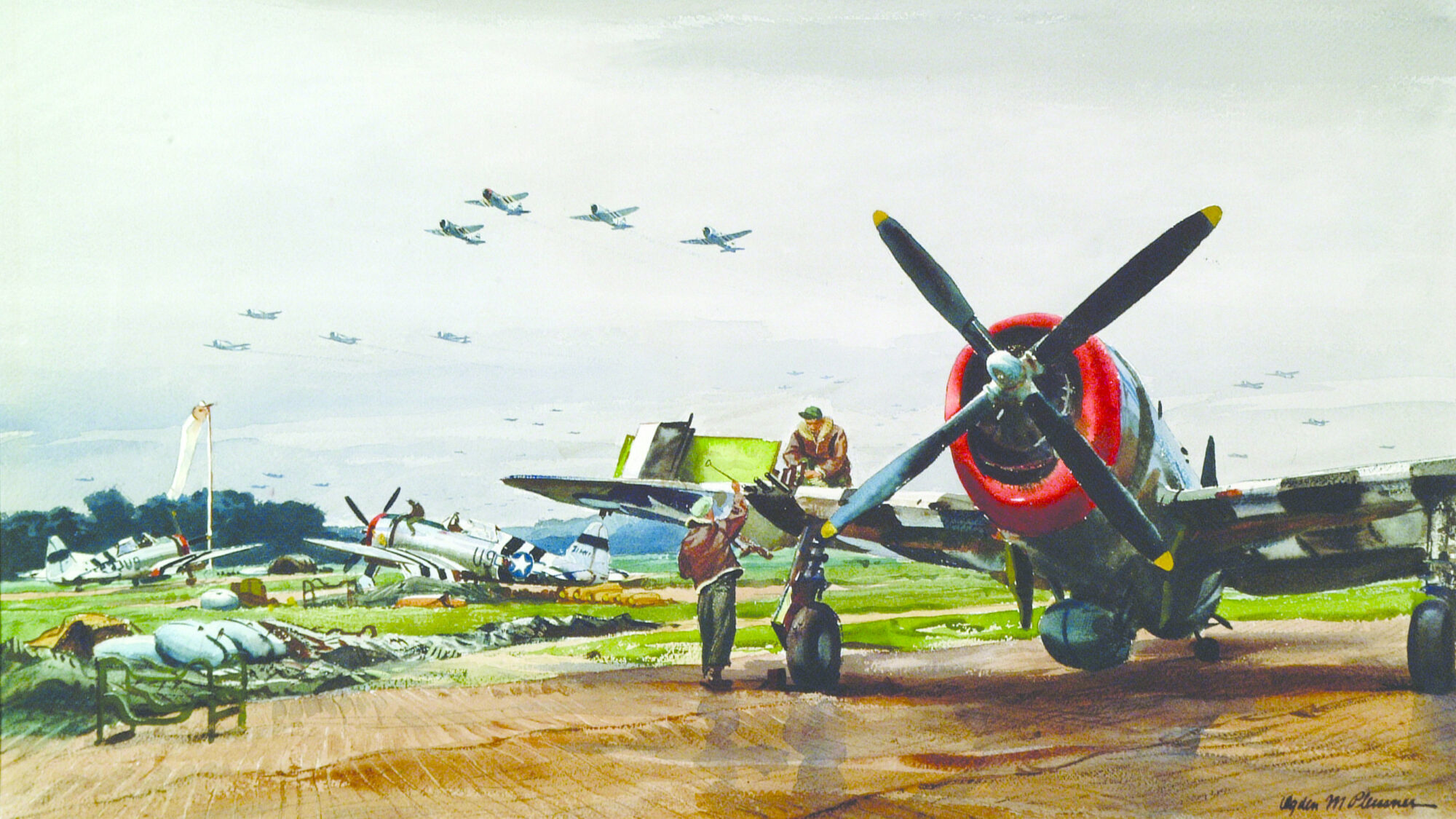

In March 1944, VIII Fighter Commander Brig. Gen. Bill Kepner authorized the establishment of a special squadron of P-47s to develop strafing techniques. For a month, pilots from four groups experimented with low-level mock raids on their own airfields; then they carried out operations in France. They would go in high and then dive down to treetop altitudes while about 20 miles from their target, so as to be at strafing altitude about five miles out. On April 12, the special unit disbanded and the pilots returned to their groups to teach their squadron mates the new tactics. The VIII Fighter Command began scheduling regular fighter sweeps.

Ground Attack in Western Europe

After the defeat of the Germans in North Africa and the invasions of Sicily and Italy, the Allies began turning their attention toward an invasion of Western Europe, and close air support of ground troops would be a major mission for the Army Air Forces. Planning for the invasion called for the transfer of the Ninth Air Force from the Mediterranean to England to become a tactical air force, along with the creation of a new Fifteenth Air Force to control the heavy bombers operating from Italy.

The plan also included the conversion of the Twelfth Air Force to the tactical role. By early 1944, P-47s were being turned out at an unprecedented rate, and many of the new fighter groups were equipping with them. At the same time, however, a redesigned version of the North American P-51 Mustang fighter was proving suitable for the long-range escort mission, and the P-47 units that were destined for the Eighth Air Force began converting to the P-51 before they went overseas. Consequently, the Army Air Forces began assigning P-47 groups to the newly organized XVIII Tactical Air Command of the Ninth Air Force.

Early 1944 saw a major shift in strategy in Europe as the Eighth Air Force was placed under the direct command of the Supreme Allied Commander, U.S. Army General Dwight D. Eisenhower. Eisenhower decreed that the destruction of the German air force was the main priority of the Air Corps, a decision that led to a switch in tactics by the VIII Fighter Command from fighter escort to fighter sweeps, including ground attack. The Allied air commanders wisely came to realize that an enemy aircraft destroyed was an airplane destroyed, regardless of whether the destruction took place in air-to-air combat or during a strafing or bombing attack on a fighter field.

This was a principle that the Fifth Air Force in the Southwest Pacific—whose fighter pilots had been shooting down Japanese fighters and bombers at a far greater rate than their peers had been doing in Europe—adopted in 1942. Kenney could have cared less if his fighter pilots shot down enemy planes in the air or whether they were knocked out on the ground. Finally, nearly a year and a half after Kenney adopted this tactic, air commanders in Europe were forced to do the same. The P-47 would become the centerpiece for ground attack in Europe. While it was highly effective, the ground attack role was hazardous for both plane and pilot, and many Thunderbolts were lost to German antiaircraft fire.

The Making of a Formidable Fighter-Bomber

The eight .50-caliber guns in the wings of the Thunderbolt were lethal enough, but the Air Corps developed new weapons to bolster the destructive power of the fighter-bombers. Hard points were installed to allow the carrying of high-explosive bombs or tubes for firing high- velocity aerial rockets, a U.S. Navy development that was adopted by the Army. Napalm, a jellied gasoline mixture, was used to firebomb enemy troop concentrations.

Operating down on the deck, the fighter- bombers, which included P-38s and P-51s as well as P-47s, attacked enemy airfields, locomotives, and trucks. Fighter-bombers operated in close support of ground forces, attacking enemy troop and tank columns and artillery positions. The fighter-bomber concept proved so destructive that in China, where every drop of fuel had to be transported by air across the Himalayas from India, the B-24s that had been used in the strategic role were taken off combat operations and assigned to transport duty. The reasoning was that the fuel they consumed could be put to better use moving fuel for the fighter-bombers.

P-47 Thunderbolts served with many nations, including Brazil and Mexico. The British Royal Air Force operated Thunderbolts in Asia. Thunderbolts equipped six fighter groups of the French Air Force after the defeat of the Vichy French in North Africa.

Although the accomplishments of the Thunderbolts have been overshadowed in the postwar media and press by the more glamorous Mustangs, the fighters that came to be known as Jugs performed admirably throughout the last three years of World War II. If the term “yeoman” should be applied to any Allied fighter of World War II, the Thunderbolt aircraft well deserves the title.

Sam McGowan is a licensed pilot and a resident of Missouri City, Texas. He is a frequent contributor to WWII History Magazine.

Didn’t the P-47 get a new prop somewhere in its development that made it much faster?

iirc Rovert S. Johnson got that paddle blade prop (there were a number of variants from Curtiss Electric and Hamilton Standard) in the Autumn of -43. it made a huge difference in climb atleast. Dunno how it did in speed, but the climb rate was vastly improved.

400 feet per minute better

In spring of 1945 out of Avenger field in Sweetwater Texas, at least 3 p-47s crashed while training new pilots. What could be the reasons? New pilots/unfamiliar with plane/ engine problems/plane design problems? Just curious. On pilot was

2nd Lt. Richard R. Branch. His plane crashed nw of Rotan, Texas april 22, 1945. In the middle of nowhere. My dad and family lived on a farm and ran out there. He remembers a huge engine in a big hole. My dad was 12 years old. He’s still living.