By Al Hemingway

It was supposed to be a walk in the sun, another routine mission in a remote Afghanistan village. Before the day was over, however, Marine Corporal Dakota Meyer would be surrounded by death in a vain attempt to rescue his advisory team trapped by Taliban insurgents in a lethal ambush. With little or no fire support from Forward Operating Base Joyce, Meyer and a few other dedicated individuals spent hours under constant fire bringing out the wounded and the bodies of the dead. For his heroic efforts, Meyer would become the first living Marine in nearly four decades to be presented the Medal of Honor.

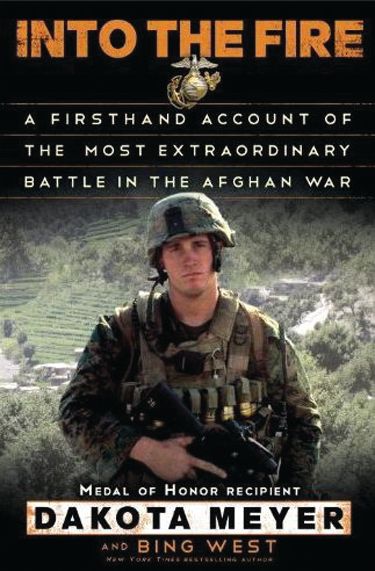

In his new book, Into the Fire: A Firsthand Account of the Most Extraordinary Battle in the Afghan War (Random House, New York, 2012, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, $27.00, hardcover), Bing West, himself a former combat Marine and Vietnam veteran, has written a gut-wrenching account of the harrowing events that earned Meyer our nation’s highest decoration. Born in Kentucky and raised on a farm, Meyer was an outdoorsman as a child. Headstrong and not knowing what he wanted to do with his life after high school, he followed in the path of his grandfather, a former Marine, and decided to enlist.

Upon completing boot camp, Meyer attended sniper school. After 80 days of grueling training he graduated and, despite warnings from his platoon commander and sergeants, volunteered for duty as an adviser to the Afghan Army. Arriving in Afghanistan in the summer of 2009, Meyer was placed in a four-man advisory team at FOB Monti, 10 miles north of FOB Joyce, in Kunar Province. The country was extremely rugged and inhabited by Islamic fighters who moved back and forth from their country into Pakistan at will.

On September 8, 2009, Meyer’s team was given the task of providing security for a joint Army-Marine-Afghan operation in the mountainside hamlet of Ganjigal, a known haven for the Taliban. The area was perfect for an ambush. “We were walking into a box canyon surrounded by high ridgelines,” Meyer said. “The horseshoe-shaped valley provided the ideal shooting gallery for snipers and machine-gun crews. I would have planned to go in there with heavy guns, armor, and air cover.”

Despite his objections, Meyer was ordered off the mission and replaced by a less experienced Marine. But before they entered into the valley, Meyer promised his team that if anything happened, he would not leave them behind. Watching helplessly at the mouth of the valley, he saw the patrol head into Ganjigal. Before long, dozens of Taliban gunmen let loose a broadside of rifle, machine-gun, and rocket-propelled grenade fire, pinning down the soldiers. Disobeying orders, Meyer and a daredevil Marine driver, Staff Sgt. Juan Rodriguez-Chavez, headed into the fray.

Driving a Humvee with a .50-caliber machine gun mounted on the turret, the two raced toward the village. In the ensuing six-hour battle, one of the most intense in the Afghan War, Meyer rescued or recovered the bodies of two dozen Afghan soldiers and Americans, plus the four dead bodies of his comrades from Team Monti: 1st Lt. Michael Johnson, Gunnery Sgt. Edwin Johnson, Staff Sgt. Aaron Kenefick, and Hospital Corpsman Third Class James Layton. The body of U.S. Army Sgt. 1st Class Kenneth Westbrook was also recovered.

Meyer criticized the Army personnel at FOB Joyce for not providing adequate artillery or air support for the patrol at Ganjigal. There was also a question of who was in overall command of the patrol, Afghanis or U.S. troops. As Meyer points out, having Afghans in charge was futile because they had little or no experience at calling in air or artillery strikes. In his epilogue, West writes: “Authority was diffuse, and no single person was held accountable. What a mess!”

Meyer criticized the Army personnel at FOB Joyce for not providing adequate artillery or air support for the patrol at Ganjigal. There was also a question of who was in overall command of the patrol, Afghanis or U.S. troops. As Meyer points out, having Afghans in charge was futile because they had little or no experience at calling in air or artillery strikes. In his epilogue, West writes: “Authority was diffuse, and no single person was held accountable. What a mess!”

Meyer has since written a letter to U.S. Army Lt. Gen. Douglas Lute, senior officer on the staff of the National Security Council, to testify to the bravery of Army Captain Will Swenson and recommend that he, too, be awarded the Medal of Honor. Swenson’s original recommendation package had been lost, but it has since been found and is currently being processed. “At Ganjigal,” Meyer wrote, “it was Swenson that I heard repeatedly calling for fires. It was clear he was running the show and was the centerpiece for command and control in a raging firefight that never died down. Bottom line,” Meyer added, “I would not be alive today if it were not for Will Swenson.”

Like many heroes, Meyer feels that he does not deserve the Medal of Honor. He did not fulfill his promise, he believes, to bring his friends out alive. Nothing could be further from the truth. Meyer not only possesses the qualities that make up a true hero but, more importantly, by his unselfish actions on that hot, terrible day in September 2009, he truly showed that he had what it takes to be a Marine.

Valor in Vietnam, 1963-1977: Chronicles of Honor, Courage, and Sacrifice by Allen B. Clark, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 288 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Valor in Vietnam, 1963-1977: Chronicles of Honor, Courage, and Sacrifice by Allen B. Clark, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2012, 288 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Vietnam veterans still carry the stigma of the My Lai massacre that occurred in April 1968, when elements of the Americal Division entered the village of My Lai and killed a large number of unarmed civilians. The tragic events at My Lai happened because of a severe breakdown in leadership and discipline, leading many Americans to believe that this was the norm during the Vietnam War.

Allen Clark, an Army veteran of the conflict and a double amputee, has collected the stories of 21 veterans, ranging from Special Forces advisers in the early days of the war to a South Vietnamese refugee desperately trying to escape the country after it fell to the Communists in 1975. Clark wants to convey to the reader that these individuals were typical of the soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines who served in Vietnam—not the aberrant behavior that surfaced at My Lai.

Clark has selected a variety of veterans to explain the complexities and hazards of serving in a conflict that had no winning strategy. The all-too familiar term of body count was the proposed method of defeating the North Vietnamese. Despite this self-fulfilling failure, he contends, the South Vietnamese still almost won the war by implementing clear-and-hold operations, pacification and a much-needed improvement of their own fighting forces. Sadly, it was too little, too late. The country collapsed.

“That unnecessary and tragic outcome need not have been,” Clark writes. “It was the doing of the United States Congress, then led and controlled by the dissident minority not reflective of the will of the American people at large, nor of course of the millions of American servicemen, who had served during the war and who, overwhelmingly, said afterward they were proud to have done so.”

A Child of the Revolution: William Henry Harrison and His World, 1773-1798 by Hendrik Booraem V, Kent State University Press, , Kent, Ohio, 2012, 252 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $50.00, hardcover.

A Child of the Revolution: William Henry Harrison and His World, 1773-1798 by Hendrik Booraem V, Kent State University Press, , Kent, Ohio, 2012, 252 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $50.00, hardcover.

Not much is widely known about the early life of our country’s ninth president, William Henry Harrison, who served the shortest term as the nation’s chief executive, dying just 30 days after being elected in 1840. Historian Hendrik Booraem V has written an interesting account of Harrison’s formative years as a young, inexperienced lieutenant serving in the Northwest Territory, present-day Ohio, in the early 1790s.

Although Harrison’s father wanted his son to pursue a career in medicine, young William opted instead to serve as an officer in the U.S. Army. Then referred to as the Legion of the United States, it was the forerunner of the modern U.S. Army, which came into existence after the term legion was abolished by Congress in 1796.

Coming from an old-line Virginia family with strong political ties, Harrison served under influential generals James Wilkinson (later discovered to be a Spanish spy) and Anthony “Mad Anthony” Wayne, where he learned firsthand the skills needed to survive in the harsh Ohio wilderness and how to fight Indians. The young Harrison distinguished himself at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, where American troops defeated a larger Indian force. When the British decided not to leave the sanctuary of their forts to aid the Indians, the tribes left their service and signed the Treaty of Greenville. The pact was signed by Wayne and others, including 22-year-old Lieutenant Harrison.

When the Legion disbanded, Harrison left the service and embarked on a career in politics. His military service would prove invaluable when, as governor of the Indiana Territory, he defeated the confederated Indian tribes under Tecumseh at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. During the War of 1812, Harrison’s forces again defeated Tecumseh at the Battle of the Thames, where the famed Indian warrior was killed and the coalition he had established was broken. The fame he won at the earlier battle led to Harrison’s winning campaign slogan for the 1840 presidential election against incumbent Democrat Martin Van Buren: “Tippecanoe and Tyler Too.” Many credit the slogan, more than the man, for winning that election.

Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps by Aaron B. O’Connell, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2012, 388 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Underdogs: The Making of the Modern Marine Corps by Aaron B. O’Connell, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 2012, 388 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Author Aaron B. O’Connell, a lieutenant colonel in the Marine Corps reserve, could not have found a more appropriate title than Underdogs for this intriguing book. Politicians and senior officers of the Army and Navy have argued over the years that the leathernecks are really not needed and that the Marine Corps, the smallest service branch, should be abolished and their members absorbed into the other branches.

O’Connell’s account specifically covers the time period from the end of World War II until the beginning of the Vietnam conflict. It illustrates how the Marines cleverly used and at times manipulated the media, the public, politicians and even their own members, creating a mystique that has endured since the end of World War I. By creating this mystique, the Corps has survived numerous attempts at its demise.

Violence is at the very core of training in Marine boot camp, used instill in recruits the basic fact that a good Marine’s primary objective is to kill the enemy. Unfortunately, as O’Connell’s book points out, this sometimes spills over into civilian life, along with the trauma and alcoholism that some Marines experienced after their harrowing battlefield experiences.

Despite all the perils, as this reviewer can attest, to be a Marine is to be part of a larger family. It is unique, for no other American military organization can compete with the magical aura that seems to surround the Marine Corps. As the author states, Marine leaders often have had to fight for their very existence. So far, like David fighting Goliath, they have been quite successful in doing so.

The Watchers: A Secret History of the Reign of Elizabeth I by Stephen Alford, Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2012, 400 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover.

The Watchers: A Secret History of the Reign of Elizabeth I by Stephen Alford, Bloomsbury Press, New York, 2012, 400 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover.

When Elizabeth I ascended to the throne of England in 1558, she was surrounded by numerous enemies bent on her destruction. The Catholic countries of France and Spain, the ruling world powers of that period, viewed England as a festering sore because of her embrace of the Protestant faith. Elizabeth, however, was no fool. The last descendant of the Tudor dynasty, she surrounded herself with loyal advisers and, with the valuable assistance of spymaster Sir Francis Walsingham, the queen developed a stable of spies and secret agents—medieval James Bonds if you will—who kept her well informed and helped bring down her adversaries.

Walsingham, a Protestant zealot who personally witnessed the massacre of thousands of Protestants on St. Bartholomew’s Day in France in 1572, was the driving force behind Elizabeth’s secret service—intercepting mail, ferreting out Catholic priests, and infiltrating Catholic inner circles. He also prevented a serious assassination attempt on the queen’s life, capturing and executing all those involved. In the end, Elizabeth’s own cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, was implicated and beheaded. Elizabeth signed her death warrant.

Alford has written a surprisingly suspenseful true-life thriller detailing the murky behind-the-scenes activities of Elizabeth’s secret service. His book is highly recommended to the reader who wants to delve into the Elizabethan world of double agents, treachery and espionage.

Blueprints for Battle: Planning for War in Central Europe, 1948-1968 edited by Jan Hoffenaar and Dieter Kruger, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2012, 261 pp., maps, notes, index, $40.00, hardcover.

Blueprints for Battle: Planning for War in Central Europe, 1948-1968 edited by Jan Hoffenaar and Dieter Kruger, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2012, 261 pp., maps, notes, index, $40.00, hardcover.

This eye-opening book deals with the strategy of both NATO and Warsaw Pact nations in Europe during the Cold War. Although numerous volumes have been written about the political aspects of that era, Blueprints for Battle delves into the military planning used by each side and how it was shaped and reshaped as the world was transformed from the end of World War II to the late 1960s.

Every detail is discussed, from conventional forces, to the use of nuclear weapons, airpower, naval strategy and logistics, in defending each opponent’s region of control in Central Europe. A series of essays written by prominent professionals in the field goes into detail about the roles the Russians and Allies used to devise numerous World War III scenarios. Defensive plans to stem invasions and the impact of world events, such as the invasion of South Korea by its northern neighbor in 1950, had a tremendous bearing on the defense of Central Europe.

Could another Cold War develop? Gregory W. Pedlow, chief of NATO’s Historical Office for nearly 25 years, does not think so. In his opinion, both the Soviet Union and the Western nations possess too many common interests for that to happen. Time will tell.

Uncommon Warriors: 200 Years of the Most Unusual American Naval Vessels by Ken W. Sayers, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 292 pp., photographs, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Uncommon Warriors: 200 Years of the Most Unusual American Naval Vessels by Ken W. Sayers, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 292 pp., photographs, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Uncommon Warriors is an informative account of the nearly 500 vessels commandeered into the ranks of the American Navy since its existence to perform a vast array of unusual assignments. Not only were many of the tasks quite irregular, so were the sources from which they were acquired. These unique ships included a pair of paddle-wheelers and coal burners, the only two that were commissioned in the Navy, a Chinese junk that saw service at Pearl Harbor, a yacht that was utilized by noted film director John Ford as an intelligence gathering ship in World War II, and a lumber-hauling boat that was used to tempt Nazi U-boats to attack her and giveaway their location.

Former naval officer Ken Sayers lists each unlikely vessel and her specifications. For those interested in maritime history, this is a useful addition to any home library.

Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby: The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia from Second Manassas to Gettysburg by Robert F. O’Neill, McFarland & Co. Publishers, Jefferson, NC, 2012, 328 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $45.00, softcover.

Chasing Jeb Stuart and John Mosby: The Union Cavalry in Northern Virginia from Second Manassas to Gettysburg by Robert F. O’Neill, McFarland & Co. Publishers, Jefferson, NC, 2012, 328 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $45.00, softcover.

The author has written a marvelous book on the Union cavalry and its leaders prior to the Battle of Gettysburg, as well as its two biggest opponents on the Southern side, James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart and John Singleton Mosby. Many Union cavalry units early in the war were relegated to nothing more than picket duty for the maze of fortifications that surrounded Washington. It was during this time that the Confederate horsemen outshined their blue-clad rivals—but a change was about to come. By acquiring younger and more aggressive commanders, the Federals’ outlook and performance began to improve, and they soon were a solid match for Stuart’s troopers.

Guerrilla or partisan warfare is discussed in great detail in the book, especially the activities of Mosby, the so-called “Gray Ghost of the Confederacy.” His 43rd Virginia Cavalry appeared out of nowhere on numerous occasions to disrupt communications and seize much-needed supplies for the Confederate Army. Included in the book are previously unpublished stories of Union soldiers assigned the boring task of guarding the far-flung outposts that protected the Union capital. The unsung efforts of Hungarian-born Julius Stahel, who assisted in shaping the combat mission of the cavalry but was later relieved by the egotistical and inept Judson “Kill Cavalry” Kilpatrick, are also chronicled at length.

Thirty Days with My Father: Finding Peace from Wartime PTSD by Christal Presley, PhD., Health Communications, Deerfield Beach, FL, 2012, 246 pp., $14.95, softcover.

Thirty Days with My Father: Finding Peace from Wartime PTSD by Christal Presley, PhD., Health Communications, Deerfield Beach, FL, 2012, 246 pp., $14.95, softcover.

For many who survive warfare unscathed physically, there are still psychological scars that can remain for the rest of their lives. Most people think of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD, as something new that emerged from the Vietnam War. Nothing could be further from the truth. Veterans of all conflicts have experienced similar symptoms and behavior in all our wars.

This book was written by the daughter of a Vietnam veteran. Christal Presley grew up in a home where PTSD permeated her everyday life. Her mother catered to her father’s mood swings and violent rages, something young Christal resented. Leaving home at 18, she eventually graduated from Virginia Tech and became a teacher in the Atlanta public school system. After 13 years, she reached out to her father to be a participant in something she called “The Thirty Day Project,” asking him many painful questions about his time in Vietnam.

This is a heartbreaking but at the same time inspirational story of one child’s determined efforts to come to terms with her father’s illness and to share his—and her—story with the children of other Vietnam veterans who may have experienced similar upbringings.

The Swamp Fox: Lessons in Leadership from the Partisan Campaigns of Francis Marion by Scott D. Aiken, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 384 pp., maps, illustrations, charts, notes, index, $42.95, hardcover.

The Swamp Fox: Lessons in Leadership from the Partisan Campaigns of Francis Marion by Scott D. Aiken, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 384 pp., maps, illustrations, charts, notes, index, $42.95, hardcover.

Do the tactics of American Revolutionary War hero Francis Marion, the fabled “Swamp Fox,” still have relevance today? That is the question that historian Scott D. Aiken, himself a veteran of the war on terrorism, answers in his newest offering. Using unconventional warfare methods, Marion terrorized British forces in the eastern part of South Carolina from 1780 until 1781. Angered by the Brits’ razing of plantations, the mistreatment of citizens and the religious intolerance demonstrated against the Presbyterian Church, Marion’s band, comprised mainly of farmers, wreaked havoc on the occupying forces. By using hit-and-run tactics to keep the British and loyalists off guard, the Swamp Fox honed his men into a very successful quick-reaction force.

Aiken believes that by closely examining Marion’s counterinsurgency warfare strategy, today’s military could rediscover methods that could prove valuable for the modern fighting man. An intriguing aspect of guerrilla warfare waged more than two centuries ago may still have significance for the army of the 21st Century.

In the Very Thickest of the Fight: The Civil War Service of the 78th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment by Steve Raymond, Globe Pequot Press, Guilford, CT, 2012, 380 pp., notes, bibliography, $18.95, softcover.

In the Very Thickest of the Fight: The Civil War Service of the 78th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment by Steve Raymond, Globe Pequot Press, Guilford, CT, 2012, 380 pp., notes, bibliography, $18.95, softcover.

Initially, the 78th Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment seemed destined for obscurity after the outbreak of the Civil War, its first commander forced to resign in disgrace. But from the Battle of Chickamauga in September 1863, when the regiment lost 100 men pushing the Confederates off the crest of a hill, to William Tecumseh Sherman’s infamous March to the Sea and the war’s conclusion, the boys from the Land of Lincoln were in the very thickest of the fight.

Through diaries, journals and letters from the participants themselves, the author has pieced together the history of a proud volunteer regiment. For Civil War buffs with an insatiable appetite to learn more about the conflict, this book is recommended. All proceeds from its sale will be given to the Civil War Trust to assist in the preservation of Civil War battlefields.

Past to Present: A Reporter’s Story of War, Spies, People, and Politics by William Stevenson, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2012, 264 pp., photographs, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Past to Present: A Reporter’s Story of War, Spies, People, and Politics by William Stevenson, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2012, 264 pp., photographs, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Reporter William Stevenson is best known for his bestseller A Man Called Intrepid, which dealt with the world of espionage surrounding British spymaster William Stephenson, whom many claim was the real-life model for James Bond. Stevenson himself has led a very interesting life in his own right. As a journalist, he has traveled the globe meeting with heads of state, spies, and other fascinating characters.

The Canadian-born writer describes his stint as a pilot with the RAF during World War II, but his globe-trotting journeys are the real meat of the book. At one time or another, Stevenson has visited China, Vietnam, Tibet, India, the Middle East, and Europe, and always managed to make his way into remote regions to talk to the natives. His exploits make for a most interesting and enlightening story.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments