By Hervie Haufler

Great Britain’s military intelligence leaders learned from their experience in World War I that the kinds of minds capable of breaking codes are a rare commodity and are often not likely to blossom in a military atmosphere. As World War II approached, the Government Code and Cipher School (GC&CS), a name deliberately underplaying the unit’s importance, was moved out of bomb-vulnerable London.

For its new home, the chief of the Secret Intelligence Service, an eccentric millionaire named Hugh Sinclair, purchased the Bletchley Park estate in the town of Bletchley, Buckinghamshire. It was a nondescript manufacturing community some 50 miles northwest of London. But for Sinclair the important fact was that it was also a railway center, located on a main line out of London and another line that connected it to Oxford and Cambridge. In August 1939, as World War II loomed inevitably, Bletchley Park became Britain’s codebreaking center, making use of the strange old eyesore of a mansion on the property while new structures were built when needed.

Bletchley Park: Their Own Small World

To head up GC&CS, Sinclair chose Alastair Denniston, who had shown brilliance as a codebreaker in Britain’s Great War intelligence center, Room 40, in London. Settling down quickly to his assignment, Denniston realized that cracking new codes such as the Germans’ machine-based Enigma system demanded special mind-sets, individuals with advanced mathematical skills, puzzle solvers, chess players, bridge addicts. He recruited such individuals, mainly from Cambridge and Oxford and launched a cryptography course to begin their training.

To have British codebreakers set apart in their own small world was in contrast to the intelligence decisions of other countries. They, including the United States, left their intelligence forces embedded in their military systems.

For the Germans in particular, this was a disastrous decision. The Nazi forces included many very bright individuals, but there were so many chiefs contending for Hitler’s favor, with each of them zealously guarding his own turf, that the capable minds among the Wehrmacht’s forces were too fragmented to be effective.

The result of all this was that Bletchley Park became a melting pot of special talent. When the war began, three of Britain’s master chess players were attending the international Chess Olympics in Buenos Aires, Argentina. They promptly caught the blacked-out, unconvoyed steamer Alcantara for home and joined Denniston’s team at Bletchley.

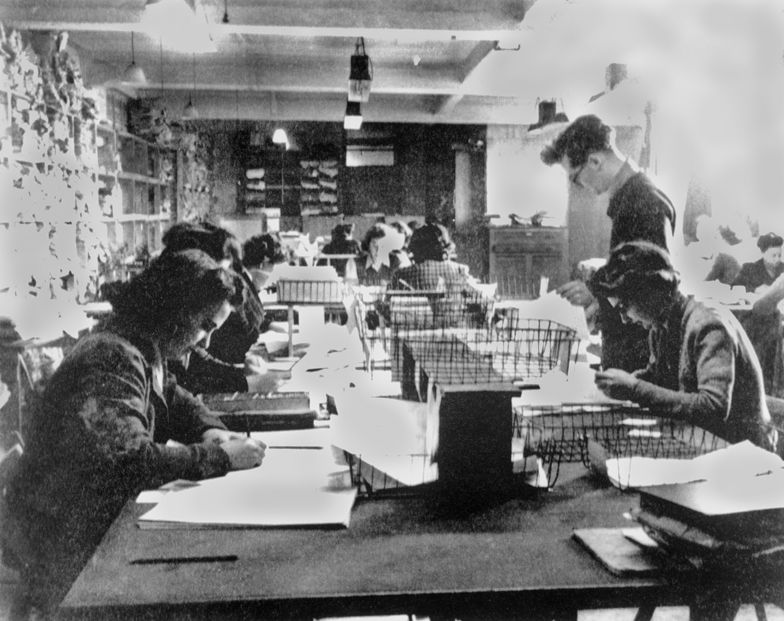

GC&CS was, in short, a society ruled by intellectual merit. Measures such as military rank did not count. Saluting was abandoned. No one was ruled out for being over age. Individuals were known by first names or nicknames. Gaining respect was a matter of doing a superlative piece of intelligence work. Bright women were signed on, whether in uniform or civilian dress.

Codename Santa Fe

I know personally of all this because, when my bad eyesight ruled me out of enlisting in anything other than the U.S. Army Signal Corps, I was trained as a cryptographer and chosen as one of the Americans to participate in the British codebreaking program.

The task of my small contingent of cryptanalysts was to help operate a radio intercept station at Hall Place, a derelict manor in Bexley, Kent, that provided both our work space and our living quarters. Our station, codenamed Santa Fe, operated around the clock, so we were divided into three shifts. We knew we were part of a British system because we had phone links with the lovely British female voices at Bletchley Park, which we knew of only as Station X. On their advice, we broke up our large contingent of highly trained radio operators and assigned each of them to a specific German military network. Collecting their transcripts, we teletyped those labeled “KR” for “urgent” via a secret line to X while holding less timely ones for Jeep transport to be picked up in London.

We cryptographers had been promoted to the rank of private first class as soon as our training in the United States had ended. At Hall Place, as we watched the arrival of our ranks of radio operators, we knew we were doomed to remain pfcs. The operators had for years been assigned to a listening post in Newfoundland, and as they entered we saw nearly every sleeve bristling with noncommissioned officer insignia. We were right. After four years I was demobbed as a pfc.

Because secret military information is ruled by the “need to know,” we pfcs at Santa Fe never learned whether these messages we were handling so carefully were ever broken. In December 1944, there came a morning when my group, just off duty, agreed mournfully over the dregs of our coffee that we had been involved in a thankless British game, a game in which message forms were merely being stacked up in some Limey warehouse awaiting the possible day when Station X would begin breaking the code. The reason for this despair was the terrible surprise of Allied soldiers being massacred in the Battle of the Bulge. The only way that this slaughter could be explained, we told ourselves, was that the codebeakers at Station X were not solving the Nazi messages.

Still, for us there was nothing for it except to continue to do all we could to supply our intercepts fully and correctly to X.

Revelations of the Past

The result of all these limitations on learning about our role in World War II was that on being demobilized postwar, we still had little real knowledge of what part we had played. When the time came for me to sign my demob papers and I had to pledge not to reveal or discuss my wartume duty, I sniffed in disdain. “Who cares?” I asked myself. And I had to hold that negative opinion for some 30 years because the British placed a security clamp on us while the Cold War raged.

When the British themselves began to let down the walls of secrecy, what a joy it was, then, to discover the real stories of World War II codebreaking. Also I learned the truth about the Battle of the Bulge. In his last-ditch effort to save his regime and himself, Adolf Hitler had planned that his attack in the Ardennes would be directed without the use of radio. Communications were handled primarily by motorcycle couriers.

Allied commanders were so accustomed to receiving advance word of German decisions that they were caught completely off guard by the Ardennes offensive. Supreme Allied Commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower was attending his valet’s wedding in Paris, while Britain’s Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, commander of the 21st Army Group, was playing golf in Belgium and had received Ike’s permission to go back to England to celebrate Christmas with his family.

For me the most important of these long-delayed revelations concerned my wartime service, the assurance that my fellow cryptanalists and I in Bexley had been, we really had been, participants in a critically important phase of the war. Oh, how my eyes devoured those first books about the triumphs, not at Station X but at what was really Bletchley Park. Along with my excitement at learning about Bletchley, I appreciated the wisdom of the British in setting up a nonmilitary structure there, in seeking out those rare individuals who could excel in codebreaking, in giving them the opportunity to contribute to Allied victory no matter what their gender, their age, or their sexual orientation.

Turing, Welchman, and the “Bombe”

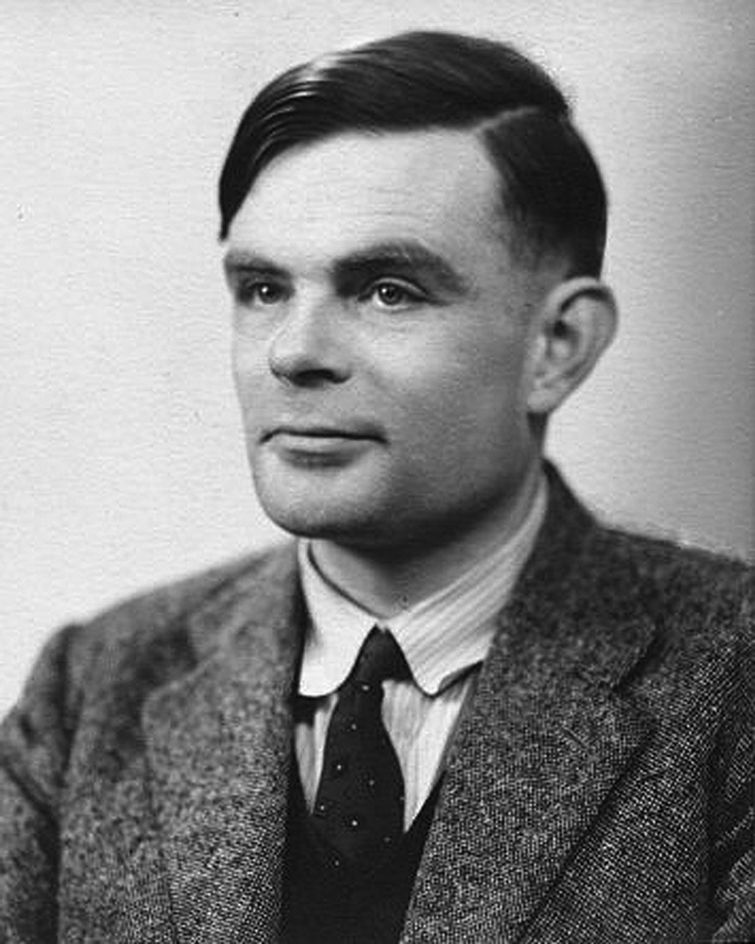

If I needed a prime example, there was Alan Turing. Turing was an eccentric young man who would never have been accepted by the military. For one thing, he was a closet homosexual at a time when Britain imposed harsh treatment on those who were exposed. Well after the war’s end, when his true sexual nature was revealed while his great World War II contributions remained secret, he was subjected to such repulsive “healing” methods that he committed suicide rather than further endure his treatment.

When war descended on Britain in 1939, though, Turing’s strange combination of talents came to the fore. He was a theoretical and mathematical genius, yet he could descend from his visionary cloud to become the most practical mechanic. This duo of virtues enabled him to lead Bletchley’s attack on the German code machine, the Enigma.

Earlier, in the 1920s, Polish cryptographers had broken the Enigma and had been using a machine they called the “bombe” to read the German messages. Turing, though, saw that the Polish analysts were doing this in the wrong way. Their bombes attacked the German machine through the message key indicators, which could be changed overnight, forcing the analysts to start over again.

With astonishing speed, Turing created a British bombe that passed over the indicators to extract the key from the message itself—a solution that permitted all Enigma messages to be broken until, usually a day later, a new key was employed. His bombe possessed the power of 12 Polish bombes.

Turing’s powerful and independent mind made him, even as a schoolboy, intolerant of conventional classroom teaching. Frequently he neglected his studies because his real attention was given to probing advanced mathematical theorems on his own.

Nevertheless, as his chief biographer Andrew Hodges reported, Turing won a scholarship to Cambridge and did so well there that he followed by winning a fellowship at the university’s King College when he was only 22. At that time, the world of advanced mathematics was centered in the United States at Princeton University. In 1936, Turing went there to study under such mathematical leaders as Albert Einstein. Princeton Ph.D. in hand, Turing returned to Britain in 1939, just in time to create his bombe and lead the attack on the Enigma.

Still, he needed the help of another unmartial Englishman to make his system work effectively. This was the overage Gordon Welchman, a lecturer in mathematics at Cambridge. Turing’s approach to cracking the Enigma was to look for “cribs,” or “probable words,” in a message. And it was true that German operators punctiliously paid respectable attention to proper officerial titles and the like. To have his machines looking for small strings of letters, however, did not produce enough rejections and led to too many “stops” that were found to be false only by hand testing. It was when Turing showed his plans to Welchman that, in a flash of inspiration, Welchman invented a technique which, in his own words, “greatly reduced the number of runs that would be needed to insure success in breaking an Enigma key by means of a crib.” His idea was incorporated into the production of a new series of bombes being produced by the British Tabulating Machine Company.

“You Dumb Bastard, Can’t You See I’m Copying?”

We Yanks at Hall Place didn’t learn about all of this inspired work by these incredibly gifted Englishmen until long after the war. More immediately, we had to deal with problems occasioned by our location just south of London. We were on the flight path that German bomber crews most often followed on their way to bomb the city. If a German crew met with heavy antiaircraft fire, it was likely to unload its bombs short of the real target and head for home. These times were, for us GIs, scary enough when there were German planes up there, but they became even scarier when the Nazis began firing their V-weapons. These rockets could be fired high over us before crashing down without warning.

Our outfit won two Purple Hearts. One was granted to a GI who, on his night off, was shacked up with his British girlfriend when a buzz bomb hit the house. The other was more deserving. This GI, a private first class, was a radio operator whose set was located near the back wall of the operations room. When a V-2 crashed down just short of the hall there, it blew out several windows. The glass above this GI shattered and fell on him, severely cutting his scalp. Even though blood was running down his face, he never stopped copying his network.

Judging the situation, the sergeant quickly ordered a reserve radio operator to tune in on the pfc.’s net. When the operator signaled he was tuned in, the sergeant bent over the injured operator and told him he could stop copying. The GI just waved him away. The sergeant then seized the guy’s pad and yanked it away from him. The GI leaped up, trying to reach his pad, and screamed, “You dumb bastard, can’t you see I’m copying?”

Bletchley Park: The Post-War Record

On being demobilized at war’s end, my mates and I had to sign pledges not to reveal what our duties had been. For me and some 10,000 others involved in the codebreaking, these pledges were honored all through the Cold War, a period of some 30 years. Then the British themselves began allowing officers at Bletchley Park to write about their experiences. I bought their books, eager to read official accounts of what we had achieved.

There was one thing lacking in these British memoirs. None of them ever mentioned that there were Americans involved. My reaction was to write a book of my own, Codebreakers’ Victory, telling of the contributions made by three different groups of us GIs.

A intelligence veteran of World War II, Hervie Haufler is the author of numerous works on the war’s intelligence history, including Codebreakers’ Victory and The Spies Who Never Were, available from E-Reads books.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments