By Peter Suciu

Thanks to movies and tV, the fez is usually associated with the Middle East, notably Turkey. It has also become a form of ceremonial headgear for lodges and fraternal organizations in the United States. As with many forms of military headdress, the history and origins of the fez are largely forgotten and filled with misinformation.

The fez originated in Morocco and spread across North Africa to the Ottoman Empire, where it became a popular form of headdress. The most accepted history is that it was worn by Andalusian Arabs in the city of Fes, Morocco, which is where the circular hat got its name. The fez was worn by wealthy Arab traders as a sign of status, likely because the red dyes needed to produce the vivid colors were somewhat expensive and stood out. Because the hat had no brim, it could be worn by Muslims during their daily prayers.

Almost as soon as it spread to the Ottoman Empire, the fez became used as a military headdress, where it initially was worn with a curtain of mail around the cap. And while today it might seem like an archaic style of cap, it was actually introduced in the 1840s as a new and seemingly Western style of headdress, likely because it was a middle ground between the Eastern-looking turban-like ketche hats and the shakos used by European armies.

Turkey’s move to a Western model of dress began in 1826 when Sultan Mahmud II suppressed the Janissaries, the traditional elite of the Ottoman military, and modernized the military. The turban was largely banned, and civil officials were ordered to wear a plain fez, which was seen as a symbol of modernity throughout the Middle East and North Africa.

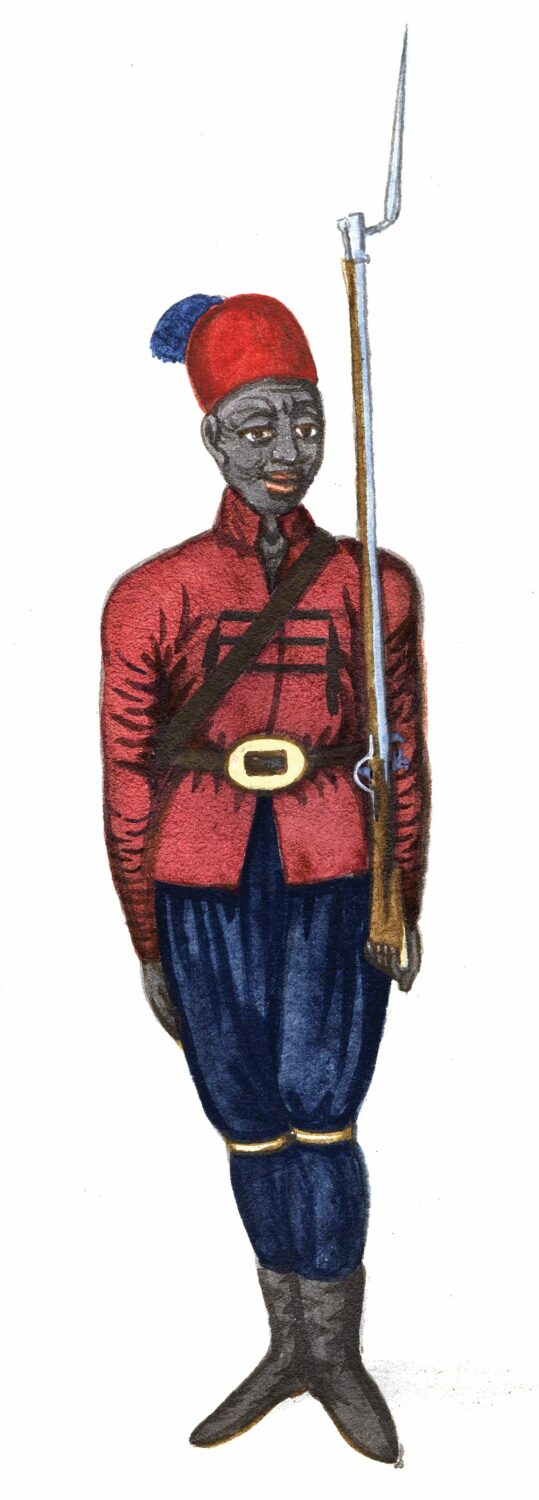

The standard headdress of the Turkish Army from the 1840s was a red fez with a blue tassel, and this remained in use until around 1900. Today it is difficult for collectors to determine what might have been a military version. “In Turkey, where there was no set pattern for the fez as this was a civilian item of dress, it was made the national headdress in 1832, and since the Army and Navy had no designated headgear, soldiers and officers wore the fez,” noted Christopher Flaherty, a collector of Ottoman Empire militaria.

Just as Mahmud II had looked to modernize the outdated Ottoman Empire’s military in the early 19th-century by introducing the fez, it was removed from active service for similar reasons when the army was updated in the years prior to World War I. The last major conflict where the fez was worn by Ottoman armies on the battlefield was the Russo-Turkish War (1877-1878). By the outbreak of World War I, the fez was officially relegated to the status of an off-duty cap.

Surviving examples suggest that the Turks continued wearing the cap, as large numbers were worn on the various World War I fronts by the Turkish forces. The fez also remained in service throughout the war with the small Ottoman navy. “It was used in Gallipoli and many examples of captured Turkish fezzes can be found in Australian collections,” said fez collector Sean O’Mara. “The fez stopped being used in Turkey around 1920.”

With the defeat of the Ottoman Empire and the founding of modern Turkey, Mustafa Kemal Ataturk actually banned the fez in 1925, but it continues to be sold as a tourist item to this day. Ironically, Ataturk wanted to ban the headdress because in the post-World War I era it was considered a Greek head covering. The Greek Army wore a soft version of the fez from its founding in 1837 until World War II, and today the Evzones (light infantry) still wear a variation on the classic fez as part of the presidential guard in Athens.

The Greeks were not the only European nation to adopt the conical headdress. The fez was also utilized by the armies of Great Britain, Portuguese Spain, France, Italy, Germany and Belgium, which generally issued it to colonial troops. Additionally, some African armies, including those in Egypt and Ethiopia, wore the fez much the way that the beret today has become a universal and cheap form of headdress.

British colonial forces, including those with Muslim units, were issued the fez, usually red and sometimes taller than the traditional Turkish versions. These included the West India Regiment, the King’s Africa Rifles from East Africa, and the West African Frontier Force. By World War I, the fez was covered with a khaki cover and neck curtain. German Askaris (colonial troops) wore a similar form of fez and cover, while French Tiralleurs, Spahis, and Zouaves, along with Belgian Force Publique troops in the Congo, wore floppy versions. Spanish fezzes were softer and shorter than the Belgian or French versions.

Bosnian infantry units in the Austro-Hungarian Army wore the fez during World War I, and these troops are often misidentified as being Turkish in period photographs. Interestingly, by the end of the war the fez was actually used more by British and Italian soldiers than by Turks.

The fez made a final comeback during World War II among the Bosnian and other Muslim volunteers in Nazi SS units. The 13th Waffen Mountain Division, which was raised in Bosnia, used both gray and red fezzes, typically with the SS eagle and skull and bones.

All this can make it very challenging for collectors today, especially as the fezzes can look quite similar. “You first of all need to decide what you call a fez,” said O’Mara. “Not all fezzes are hard round cones. The French Zouaves and Tiralleurs wore a soft rolled fez. Not all fezzes have tassels, nor were they issued with them. The Ethiopian armies wore an extremely tall fez with colorful wool tassels.”

The fez existed in many forms and was used by countless armies. The fact that civilian merchants and tourists wore the same headdress makes it very challenging today for collectors. Finding stamps or other identifying marks becomes all the more important. “When trying to identify military fezzes, it’s a bonus to find markings,” said O’Mara. “Most government- produced military items have markings of some kind. It is sometimes hard to find them due to age. Many of the markings were inked on the interior felt and vanish over time. The reason many British markings still exist is because they in most cases used a sort of paint and not standard ink. So the markings are more durable.”

Of course, to every rule there is an exception—not all British fezzes are inked. “A debossed arrow along with date and maker’s details on the sweatband marks the King’s African Rifles red fezzes,” added O’Mara. “This is pretty unusual and more akin to a civilian fez. But then these items were specialist and made by civilian hat makers. You find many different markings by different makers for the same type of fez.”

The end of World War II was not the end of the fez. “The Royal Egyptian Army continued with the fez as military headgear till the end of the Royal Kingdom of Egypt in 1953, and only after the Egyptian national revolution was it abandoned,” said Flaherty. “In the case of British and Sudanese troops, their fez was still a ceremonial item of dress.”

The quality of the military fez can vary, and while many are nothing more than a floppy cloth or felt cap, some are of very high quality. Flaherty described one fez in his collection as made of a “fine cherry wool cover, with leather sweatband, cardboard-reinforced top, and a maker’s tab to a Cairo maker displaying the Khedive crest of three crescent stars, typical of pre-1914 construction.”

With so many variations, what can collectors do? The first thing is to buy from respected and trusted sources. Beyond that, it can takes years of experience to master determining what is a real military fez and what was just brought back by a tourist who visited the Middle East years ago. “First of all, the best way to tell is to actually handle fezzes,” said O’Mara. “There are thousands of civilian types of fezzes used, from the German salt mines to the coffee houses of Cairo. Most military fezzes are government issue.”

As with many military caps, private purchases can complicate matters. “The Italians preferred to have their own fezzes made to order,” said O’Mara. “So if you collect Italian World War II fezzes, you will find home-made to private purchase, with government-issue in between. However, these types of private purchase fezzes were not worn by civilians.”

As with any collectible the best place to start is to look at period photographic evidence to see what shape the fez was. Did it have a tassel or not? How tall was it, were badges used, what color was it, and where was it used? “The tassels on military fezzes were used to great effect and denoted regiment and status,” noted O’Mara. “You can see this on Ethiopian, British, and French fezzes. On Zouave fezzes, rank was expressed on the tassel and also in the fez construction, with some fezzes having blue rings in the fabric which indicated rank.”

Where it gets more confusing for collectors is that the majority of military fezzes from Egypt, Turkey, and Eastern European armies are similar to those worn by the civilians. In these cases, best judgment may be necessary. Fortunately, the prices are reflected by this, and most Egyptian and Turkish fezzes are seldom more than a couple of hundred dollars. Even colonial fezzes are typically found for around the same amount due to limited collector interest. Waffen SS fezzes, however, can often run more than $1,000, and unfortunately these are now among the most commonly faked as well.

Again, it comes down to knowing what to look for. “There are about three different types of Handschar fezzes,” said O’Mara. “Green and red short-cut soft fez with distinctive tassel, conical fez with no tassel. You will find them in different shades, but generally it is easy to tell a real one. You see many concoctions being sold—hard-shell fezzes with metal badges and so on. I personally think the best way to start is look at the photographic evidence and then visit museum collections as your starting point.”

In most cases with European fezzes and their respective colonial forces, it is worth noting that the military fezzes are not the same shape, construction, weave, or material as a civilian fez. “Just looking at and understanding the material weave can help you tell where the fez was from and which army it belonged to,” noted O’Mara. “That is why it is very easy to spot fake Handschar fezzes. But the main point of difference in 90 percent of military fezzes—with the exceptions noted—is that the shape and tassel will not be the same shape, size or construction as a civilian fez. So avoid your standard fez with a badge stuck on it unless you can get some history of its origin.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments