While most images of a tourist trip to Hawaii have to do with beautiful beaches, hula skirts, and great surfing, a student of history must make it a point to visit two sites, Pearl Harbor and the Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific, commonly referred to as the Punchbowl because of its distinctive location within the crater of a extinct volcano in sight of modern downtown Honolulu.

Thousands of graves are marked with headstones that reveal a litany of sacrifice during World War II as American forces advanced across the expanse of the largest body of water on the face of the Earth. Medal of Honor winners rest near others, known and unknown, who gave their lives fighting the Japanese. However, if a more poignant sight is possible, just beyond, in the Garden of the Missing, stand long pylons bearing the names of many more service members whose final resting place is unknown. The tribute to these individuals whose earthly remains may never be located is fitting and somehow set apart from those who lie buried in the soil of their native country.

The effort to locate the missing and presumed dead of World War II has continued almost since the day the guns fell silent more than 65 years ago, and the search parties have not only been American. Teams of military and forensic experts from all the former warring nations have conducted expeditions into the jungles, beneath the waves and across the mountain ranges of the Pacific.

By far the heaviest losses sustained during the war were suffered by the Japanese, and last October another expedition trekked to the island of Iwo Jima, where U.S. Marines landed on February 19, 1945, to wrest control of the inhospitable, pork chop-shaped spit of volcanic land from a defending garrison that had honeycombed miles of tunnels beneath the ground and through the sides of Mount Suribachi, which towers 550 feet above the now silent beaches.

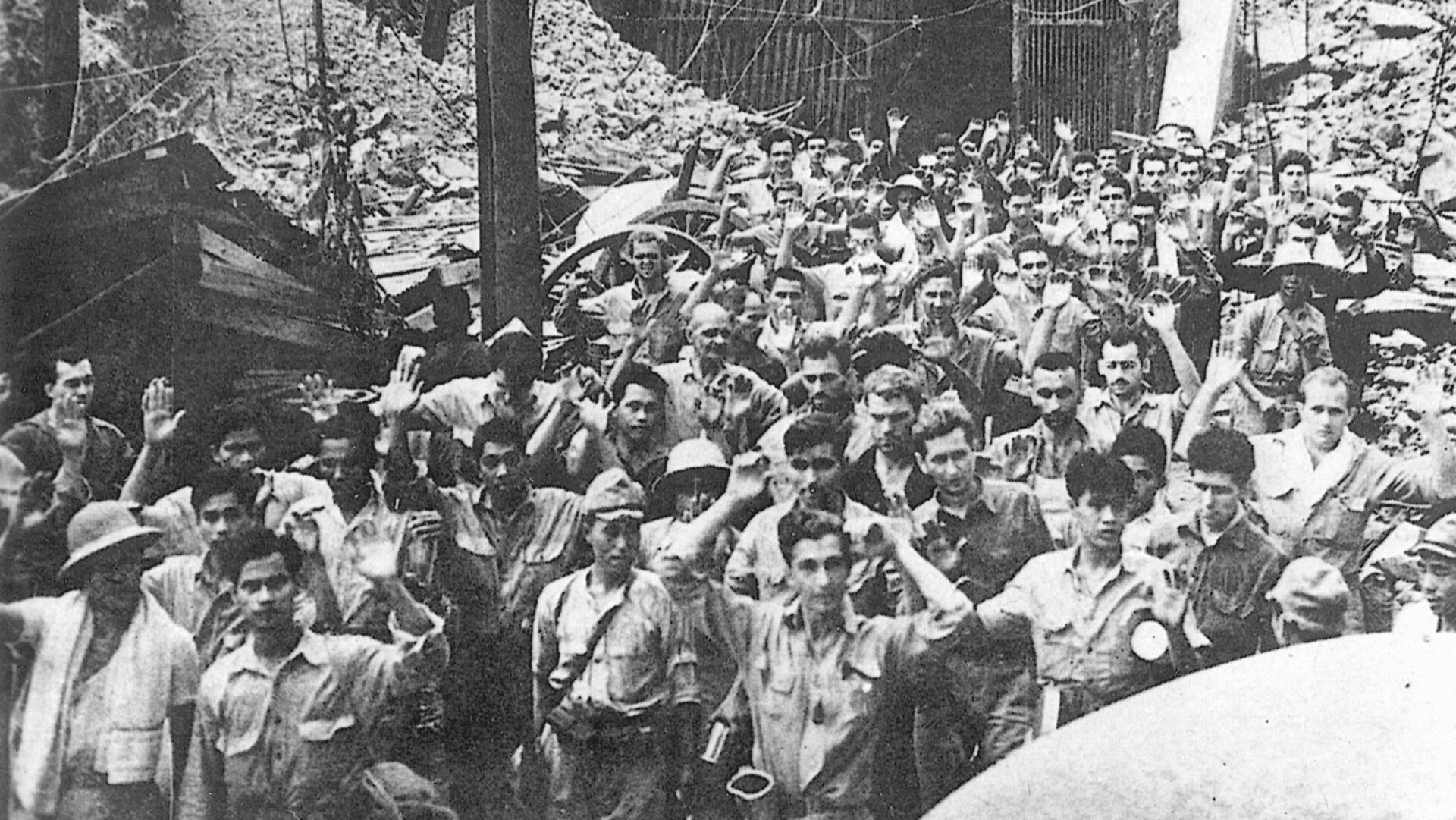

Nearly 7,000 Americans died in the fighting, which lasted more than a month before the island was declared secure on March 26, and the Japanese fighting on the island were virtually annihilated. The American dead were temporarily buried on Iwo Jima or transferred to ships offshore. All of the U.S. dead whose bodies were located were eventually repatriated.

The story for the Japanese, on the other hand, was quite different. More than 22,000 soldiers of the Rising Sun perished in the horrific fight, and up to 12,000 of these were never identified or recovered. Some of the defenders were trapped in their underground caves, which became tombs when U.S. engineers sealed the entrances with satchel charges or tanks and flamethrowers spewed fire, burning the occupants to death or depriving them of oxygen. After the battle, thousands of Japanese corpses were interred by the victors in mass graves marked only on maps as collective burial sites.

The Japanese recovery team that ventured to Iwo Jima last autumn explored two areas listed by the Americans years ago as enemy cemeteries. They searchers discovered the remains of 51 soldiers, and the sites may contain the bodies of as many as 2,200 of the nation’s fallen. A representative of the Japanese Kyodo News Agency confirmed for the Associated Press that the recent discovery was the most significant in decades. The Japanese Health Ministry will conduct further excavations of the sites on the island now known as Iwo To, and the operation is expected to last several months.

One site is located at the foot of Mount Suribachi, which U.S. Marines climbed on the fourth day of the fighting to plant the American flag atop the promontory for all below and at sea to view. The other site is near one of the contested airfields which was captured by the Americans and later used as an emergency landing strip for crippled heavy bombers returning from raids against the Japanese home islands.

Although most of the family members and friends who waited in vain for their loved ones to return from battle to the United States, Japan and so many other countries have passed away by now, succeeding generations continue the quest to bring the dead home for proper burial and to receive the military honor that is long overdue.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments