By Volker Griesser

Background: Fallschirmjäger Regiment 6 was organized in February 1943, under the command of Major Egon Liebach. It was part of the 2nd Fallschirmjäger Division and was stationed in France, where it trained in parachute and glider operations. It saw action in Italy and participated in the capture of Rome when Italy capitulated and where it battled against Italian troops and partisans.

In November 1943, 2 FJD and FJR 6 were redeployed to the Russian Front, where they fought courageously throughout the brutal winter and into the spring of 1944. After suffering heavy losses, FJR 6 returned to Germany for refitting and eventual deployment to the Normandy region of France.

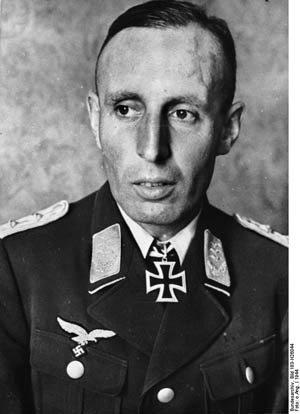

During this period, Major Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte, who had commanded the 1st Battalion of the 3rd Fallschirmjäger Regiment during the Battle of Crete in May 1941 (and for which he was awarded the Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross), became commander of FJR 6. Most recently he had been the operations officer of the 2nd Fallschirmjäger Division.

Fallschirmjägers in Normandy

In order to strengthen the defense against the anticipated Allied invasion of Northwest Europe, Major Friedrich August Freiherr von der Heydte’s Fallschirmjäger Regiment 6 was relocated in mid-May 1944 from Elsenborn, Belgium, via Maubeuge, Amiens, Rouen, and Caen to the narrows of the French Cotentin peninsula.

Tactically, FJR 6 was the assigned reserve unit for the LXXIV Corps, and the regiment adopted a switch position between Mont Castre and Carentan. The regimental staff was in Gonfreville, north of Périers, the 1st Battalion under the command of now-Hauptmann (Captain) Emil Preikschat in the area from St. Jores and Monte Castre, the 2nd Battalion under Hauptmann Rolf Mager near Lessay, and the 3rd Battalion under Hauptmann Trebes between Carentan and Périers.

In their planning, the corps assumed that the Fallschirmjäger were the best candidates for anticipating the modus operandi of the Allied air-landing operations, and therefore the best able to go up against them. The regiment was assigned to the 91st Airborne Division, under II Fallschirm Corps.

In expectation of the enemy attack, Major von der Heydte kept the Fallschirmjäger busy. In addition to the usual patrols and night-time aircraft scouting assignments, he ordered smaller exercises. According to General Eugen Meindl’s battle instructions from May 11, 1944, a third of the troops always had to be in position day and night in the possible landing zones.

Amongst other things, the goal was for the Fallschirmjäger to become accustomed to the terrain of Normandy, and to improve how they used natural and man-made positions. Von der Heydte put in place effective defensive arrangements; aircraft observation posts were created, with anti-aircraft guns arranged in a 360-degree pattern covering every attack altitude. Furthermore, whole fields were planted with “Rommel’s asparagus”—long wooden poles designed as air-landing obstacles in order to prevent military gliders from landing.

Under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Erwin Rommel, who pushed the building of coastal fortifications with great urgency, whole stretches of land were flooded, turning into death traps for parachutists. On the coast, the rule of thumb was to allot one division for every 10 kilometers of defensive line.

FJR 6, however, was assigned an area 20 kilometers wide and 15 kilometers deep, and therefore had no systematically arranged bunker positions. Once more, this shows the army leadership’s almost limitless trust in the combat power of the Fallschirmjäger, because this key position secured the overland entrance to Cherbourg. An Allied landing on the Cotentin peninsula could build into a wave might roll into the heart of France.

What concerned von der Heydte even more was the uneven tactical perspective held by diverse commanders. Rommel, who visited the regiment in its positions shortly after his arrival, proposed that the invasion be defeated directly on the coast, practically at the water’s edge, while Generalfeldmarschall von Rundstedt wanted to let the enemy set foot on the coast, in order to close in on him with armored counterattacks and drive him back to the ocean.

A Regiment Unprepared For Ground Combat

The regiment’s neighboring units were as diverse as the tactical opinions about how to handle the invasion. Battle-tested troops with experience on the Eastern Front were located next to reserve units with outdated material and captured weapons, and eastern battalions consisting of volunteers and former Russian prisoners of war. The Fallschirmjäger realized that they had only themselves to rely upon in the upcoming battles.

The higher powers of the army recognized the heterogeneous nature of the defensive forces in Normandy, and demanded that every base commander give his written word of honor that no matter how desperate things became, he would hold his position and not desert it. Without suffering any consequences, Major von der Heydte, however, refused to sign this on the grounds that it was dishonorable.

At this time, the regiment had access to 70 motor vehicles. This fleet consisted of around 50 different brands and makes, so repairs and parts replacement became a logistical nightmare. In a brief period of time, many of the vehicles failed and had to be retired because of mechanical problems and damage. Even though the regiment was well equipped for infantry deployment, they were seriously hindered by the lack of motorized mobility.

The promised antitank guns also never materialized; at the beginning of June, von der Heydte wrote to General Kurt Student [head of German airborne forces] saying that they were “completely prepared for any air-landing invasions, but only partially prepared for ground combat because of insufficient anti-tank weapons and a lack of vehicle equipment.”

Signs of an Imminent Invasion

In the first days of June, indications of an enemy invasion spread. Encoded radio transmissions from the French Resistance were intercepted, and Luftwaffe reconnaissance did not miss the increase in enemy air transport formations in southern England. Telephone connections were regularly cut, and often the German units’ communications with one another depended on the activities of the resistance and the ability of signalers to repair the wires. It could only be days before the invasion happened; the enemy waited only on the weather and the tide.

Eugen Griesser [the author’s grandfather] remembers this time well: “In the days before the invasion a tense mood reigned. Everyone knew that the invasion had to come; we just did not know when and where exactly. The resistance continued to make trouble, cutting electrical wires, shooting up individual vehicles, and so on. On June 2 or 3, a farmer who was friendly to the Germans gave us two rabbits that he had slaughtered. The day after, we went to pay him a visit and offer our collective tobacco rations in thanks. We found him lying in his clean living room with a crushed-in skull; his wife and children had disappeared. Someone, probably his murderers, had drawn the sign for the resistance in coal on the wall.”

Given such events, the Fallschirmjäger were especially vigilant.

When the Alsatian drivers of the regimental supply train all deserted, one thing became clear: soon it would start! On June 5, Allied bombers attacked tactically important points such as bridges, roads and railway stations. The 3rd Battalion carried out a map exercise for its officers and platoon leaders; they focused on the destruction of an enemy airborne operation in the battalion’s staging area.

The highest powers of the army planned a war game/map exercise in Rennes for the morning of June 6, 1944; it would be led by the Chief of Staff of the Wehrmacht, General Walter Warlimont. All division commanders with their staffs were required to participate, along with the commanders of units of troops that were subordinate to the army and the respective corps.

This order also affected Major von der Heydte. Because he planned to drive to Rennes with General Erich Marcks, the commander of the LXXIV Corps, he decided not to depart on the evening of June 6, in order to use the protection of the dark to make it to Rennes, but instead to spend the night with his regiment because of the critical overall situation. During the daytime the Allied planes darkened the skies; therefore the departure with General Marcks was planned for 5:00 am on June 6.

During the night of June 5/6, the communications officer of FJR 6, Oberleutnant Dietrich, received word from Luftwaffe command that the Allied air transport units stationed in England were showing signs of heavy activity. Dietrich reported to Major von der Heydte. Contrary to the relaxed approach of his superiors, von der Heydte ordered his regiment to prepare to march and for battle. Ground observers had already been assigned to track the Allies’ movements in the night sky and report anything suspicious.

While the battalions prepared, Oberleutnant Dietrich had the assignment to inform the neighboring army units. The radio connection, however, refused to function; they could not figure out why. Acting more out of desperation than anything else, Dietrich tried to establish a connection via the French public telephone network, and surprisingly it worked. Apparently the resistance had scruples against harming property of the French state.

Major von der Heydte finished a late dinner and shaved, “in order to appear respectable going into a possible battle,” he explained later in his memoirs. Shortly after midnight, the first reports from the ground observers arrived: enemy paratroopers were landing between the coast and Carentan.

Shortly thereafter, they received the news from the 3rd Battalion that enemy paratroopers had landed north of Carentan. It turned out that the men of FJR 6 were the first to identify enemy soldiers having landed in Normandy; in this case, it was the pathfinders of the U.S. 101st Airborne Division, who had landed between St.-Côme-du-Mont, Baupte, and Carentan, in order to direct with light signals the paratroopers who followed. Exactly seven minutes after midnight, a ground observer noticed approaching enemy transport planes and reported them to the regimental command post.

The Allied Plan to Take Carentan

The Allied plan involved the following strategy. In the morning hours of June 6, U.S. and British combat troops—supported by Polish, Canadian, and other Allied contingents—were set to land at five different points on the coast between Quineville and Ouistreham and form bridgeheads. As quickly as possible, they were supposed to expand and consolidate these individual bridgeheads by landing heavy armor.

An airborne attack by British paratroopers on the bridges over the River Orne and the Caen Canal would support the landings by sea, as would an attempt by American paratroopers to take the town of Carentan. In this latter sector, the Allies had divided the beaches into two areas with Carentan as the decisive point between them: the beach northeast of Carentan was called Omaha, while the beach directly north of Carentan was Utah. As long as this town was in German hands, these two sections could not be consolidated, and there was a real danger that German forces could isolate and annihilate the American troops deployed on Utah Beach.

The leaders of the Allied troops decided that landing soldiers by sea only would be too costly in lives and materials. Yet they believed the German coastal defences to be stronger than they actually were. The powerful Allied paratrooper units and airborne infantry that were deployed behind the backs of the defenders were supposed to pull German forces away from the coast and lock them in the interior, in order to weaken the resistance on the beaches and simplify the landings there.

The western flank of the landing zone became the area of operations of the U.S. 82nd Airborne Division and the U.S. 101st Airborne Division, two particularly powerful divisions of paratroopers and airborne infantry. They were assigned to form a bridgehead between St.-Marie-du-Mont and St.-Germain-de-Varreville, west of Picauville at Merderet and northwest of Carentan. They planned to blow up the bridges over the Douve and occupy the causeway over the Merderet, in order to make the advance towards Cherbourg possible. Similarly, the western outlets of the dam near the Utah Beach section had to be taken, so that the advance from the landing zone into the interior could take place without losing any time.

Prior to the invasion, recon aircraft had already supplied the Allied planners with photographs of the area of operations. They had recognized the artificially constructed flooding at the juncture of the Merderet and the Douve, but they had overlooked the swamps to the north, which had been created to defend against airborne operations, and reached to the Carentan-Cherbourg railroad’s embankment. This oversight was due to the dense vegetation growth in and around the water west of Ste.-Mère-église that made, for example, La Fière appear to be fields and pastures. What actually awaited the American paratroopers there was a 600-meter-wide flood.

“Something Was Coming Our Way!”

Rudolf Thiel, an Obergefreiter [private] in the regimental combat platoon, remembers what happened on the night of 5/6 June: “Arthur Völker, my bunker mate, had indigestion. He believed that this always happened to him when something was in the wind. I, too, could not hide my inner unease. After the relative quiet of the past weeks, I was worried about the massive bombings of the interior. Something was coming our way!

“The rations had been miserable again that day: lots of pearl barley and a little fish, a lot of marmalade and a little sausage. We hoped it would stay quiet that night and that there would be no false alarms. Arthur and I were assigned duty on the high lookout post, an airy, windy task. A strong breeze blew in from the sea; now and again the moon shone through the clouds. It was not cold, just nippy; there on the high perch one got really knocked about.

“At 2400 hours I had to relieve Arthur; until then I tried to catch a few winks of sleep. It didn’t work, sleep wouldn’t come. My unease grew stronger from hour to hour. I tried to read by the light of my Hindenburg light, but I could not concentrate. What the devil was being set in motion out there? The night was so calm, there was no noise of motors. Only the wind blew through the poplars. I had to relieve Arthur soon, and because I couldn’t sleep anyway, I decided to relieve him earlier than scheduled.

“I dressed, belted up, checked my submachine gun and magazine, and crawled out of the bunker. The fresh air made me shudder slightly and I listened carefully to the night. It was strange; this much quiet wasn’t normal. I had the feeling as if something treacherous was lying in wait for us. I went to the observation perch and called up: ‘Arthur, come down. I can’t sleep and will relieve you now!’

“Arthur climbed down the ladder and said: ‘Shitty wind, the damned cold, nothing particular to report’ and disappeared into the darkness. I climbed up to the perch and looked at my watch. Ten minutes to midnight. I hung my field glasses around my neck, loaded and secured my submachine gun, and made myself comfortable. After a few minutes I heard the familiar but distant noise of airplane motors. ‘Donnerwetter,’ I thought, ‘that’s not just a few. Hopefully they’re not going to unload on us.’

“I looked at my watch again and held the binoculars up. It was 0007 hours when I looked to the northwest and saw all kinds of red flares and glaring white light signals. That could only mean one thing to any experienced soldier: The enemy is attacking!!!

“My mind told me: this is the invasion. After the initial moment of shock, like a crazy man, I turned the crank on the field telephone that connected the observation post with the regimental command post.

“Right away I was connected with the service’s clerk who sat next to the telephone. ‘Obergefreiter Thiel reporting, combat platoon, red and white light signals sighted direction northwest, loud airplane noise, the enemy is attacking!’ The phone at the command post was not hung up right away, so I heard how Oberleutnant [1st Lt.] Peiser gave the clerk the order to get the Major right away.

“Then I heard the quick steps of the Major and fragments of his speech: this afternoon–French–damn it–no alarm. The Major: ‘Combat platoon, report!’ I said: ‘Obergefreiter Thiel reporting, combat platoon. A large amount of light signals in the direction of the coast and Cherbourg. The enemy is attacking. This is the invasion, Herr Major, should I sound the alarm?’ I looked at my watch: 0011 hours. The Major: ‘Sound the alarm. Send Oberfeldwebel [Platoon Sergeant] Geiss to report to me immediately!’ He hung up. I, too, hung up, and yelled as loud as I could: ‘Alarm! Alarm!’ And again and again: ‘Invasion, invasion!’

“While doing so, I shot out two full magazines of submachine-gun ammunition. I climbed down from the perch and Oberfeldwebel Geiss and other comrades were approaching me, looking sleepy and distraught. Everyone thought that it was just an air alarm, because an airplane motor inferno reigned above us. Oberfeldwebel Geiss sprinted to the command post, we took to our positions and our foxholes and waited for the unknown monster: invasion!”

“Alarm–Parachutes–Military Gliders!”

Because of the reports of his ground observers, Major von der Heydte ordered his regiment to march in order to confront the enemy. The scattered state of his battalions was not exactly conducive, however, to such a massive relocation.

After midnight the Fallschirmjäger received reports of the first battles against American paratroopers south of Carentan. The 3rd Battalion encountered the enemy first between St.-Georges-de-Bohon and Rougeville, where three companies of American paratroopers landed. The 13th Company of FJR 6 absorbed the enemy fire and achieved good results against the Americans, who were disoriented by the night-time landing in an unknown area.

Obergefreiter Günter Prignitz in the 13th Company notes: “St.-Georges-de-Bohon lay about 14 kilometers behind the coast. I belonged to the company troop of the 13th Company and lay with a total of 16 men divided into four tents, directly next to the churchyard. We had placed a regular observer with a battery commander’s telescope in the church tower. A half an hour after midnight on June 6, I heard our ground observer calling: ‘Alarm–parachutes–military gliders!’ while firing off his weapon.

“The first thing I heard when I left my tent was an American soldier who had landed in a giant tree, saying ‘Oh, oh, broken leg!’ His parachute still hung in the treetop, and he was on the ground. I disarmed him and spoke calmingly to him. His wounds weren’t bleeding. He was probably the first American prisoner of war of the battle of Normandy.

“A second parachute lay laterally across one of our tents, the paratrooper who belonged to it, however, was not to be found. A Feldwebel ran around to the back of the tent and yelled: ‘Halt! Password!’ Only at daybreak when we found him dead did we understand why the American hadn’t reacted.”

Units of the 101st Airborne Division jumped between 1:00 and 2:00 am, but their landings were heavily dispersed. They were unable to band together, and FJR 6 attacked immediately. The 3rd Battalion reported that Oberfeldwebel Peltz was bringing in the first prisoners of war. They were locked up in the church of St.-Georges-de-Bohon for later questioning.

Günter Prignitz remembers that “Numerous battles with American soldiers took place around our tents and soon we had 30 to 40 prisoners locked up in the church.”

Alfons Mertens, at the time a Fahnenjunker-Feldwebel (officer candidate sergeant) in the regimental signal communication platoon, noted the confusion of the night: “The communications situation the night of June 6 was anything but clear. We couldn’t get any connection to the neighboring units or senior positions. Partisans and sabotage groups had cut the wires, so we had to send out messengers and maintenance men to establish contact with the other units. One of my messengers, a young boy who had just turned 18, returned to me in the morning, distraught. I had sent him to the headquarters of the 91st Airborne Division; he had found the headquarters deserted and destroyed. He had found the commander of the division, General [Wilhelm] Falley, lying shot dead on the side of the road. At that point, at the latest, it became clear that we only had ourselves to rely upon in the next few days.”

First Contact Between Fallschirmjägers and U.S. Paratroopers

At 4:00 am the American paratroopers landed in the area of Raids [located about 15 miles southwest of Carentan on the road to Periers] and once again, after an exchange of heavy fire, the invaders were defeated. In fact, the Germans managed to take prisoner a major, a captain, a lieutenant, and 73 other ranks. The remains of the enemy landing force pulled back to the southwest.

Eugen Griesser notes the first contact between the Fallschirmjäger and the Americans: “The American paratroopers were mostly young boys around 20, big and strong guys. They wore combat uniforms with sewn-on pockets in which they carried around half a colonial-wares store: rations in cans, chewing gum, chocolate, reserve ammunition, pictures of naked girls, and even explosives. It was no wonder that some of them just exploded under fire from the rifles.

“Each of them had a large combat knife tied with a bootlace to their lower leg. Many others had a second dagger on their belt, a jackknife in their pants’ pocket, and a pocketknife in their jacket pocket. The American pocketknives were very useful, because not only did they contain a knife blade, but often also a saw, bottle opener, an awl and a small screwdriver. Unfortunately I lost my American pocketknife later.

“The Americans were equipped with small metal frogs for their night-time attack. They were a child’s toy that clicked when you pressed on it. The idea was that they would communicate through this clicking and be able to recognize each other. At night, sounds carried especially far, and therefore this idea that the Americans had, to communicate in the dark with these children’s toys, wasn’t very intelligent. If they instead had ribbited like a frog, no one in the swamps would have noticed it, but the sound of these metallic clickers was so clearly unnatural, that one would have had to be deaf not to notice it.

“Oberfeldwebel Peltz took some officers prisoner from their scouting groups early in the morning. They were crowded around a map, shining their dim flashlights on it. They were so concerned with reading the map that they didn’t even notice that they had been encircled. They also hadn’t set guards; these guys were that sure of their victory.”

At 6:00 am on June 6, Major von der Heydte arrived in Carentan to interrogate the captured Americans. The pathfinders of the 101st Airborne Division were particularly striking; they had shaved off their hair except for a thin stripe in the middle, and they had painted their faces with red and white. “Now they’re sending us their Indians,” Hauptmann Trebes said as he led Major von der Heydte to the prisoners.

Except for the usual information, including their name, rank, unit, and age, the Major received no other information from the Americans. However, the deployment of elite divisions such as the “Screaming Eagles” was enough evidence that this mission was no localized attack, but that it had to be part of a larger-scale operation. This information was directly passed on to LXXIV Corps, except for the neighboring 709th Infantry Division, with whom they could not communicate.

The enemy engaged the command post in St.-Georges-de-Bohon with mortar fire. It only had limited effect, however, and Oberleutnant Prive took action against them with an assault detachment from Rougeville; he drove the enemy back towards St.-Georges-de-Bohon. Caught in this pincer attack, and surprised by this textbook maneuver, the Americans had no adequate response. Prive’s platoon took more than 60 prisoners in this action.

Later on, some of the American units’ stragglers came voluntarily with hands lifted to the Fallschirmjäger’s positions. At this point the situation became clear: those Americans who had landed near the 3rd Battalion west of Carentan were probably dropped in the wrong place; those paratroopers captured south of Carentan were probably part of a diversionary maneuver or a reinforced recon operation. The enemy paratroopers’ main attack could be found in the direction of the coast or farther west by Ste.-Mère-église.

Major von der Heydte’s First Combat Orders

From the north, the Fallschirmjäger heard the noise of more fighting. Coastal Defence Battery W5 lay in that direction and farther up the coast towards Cherbourg was the Marcouf Battery. There was supposed to be an anti-aircraft unit in Ste.-Mère-église, therefore it was possible that these positions had already taken combat fire, similarly for the army unit at St.-Côme-du-Mont.

Major von der Heydte decided to travel towards the sounds of battle in a sidecar motorcycle to investigate. In his memoirs, he describes the situation: “On a narrow street, enclosed by bushes, I came to the place called Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, which, according to the map, was the last built-up area before the coast. In the middle of the village there was an old church with a pretty and very tall tower. After we had gotten a hold of the key to the tower, I climbed it and had a unique gorgeous picture in front of me that I will never forget. The ocean lay before me, deep blue and practically motionless. On the horizon numerous battleships lined up in an almost closed chain. Between the ships and the shore there was a brisk back-and-forth traffic of craft that were transferring the American soldiers to the shore.

“The Americans only met resistance from a single German bunker that—from my point of view it was to the right of the ships—was shooting at the landing soldiers. The Americans tried to take cover from the fire, in as much as it was aimed at them, with artificial fog [smoke]. I only needed a few minutes to get a clear impression of what was going on here. The location Sainte-Marie-du-Mont was not occupied by German troops; according to the signs in his office, the local commander appeared to have left in a hurry.

“I, too, had no reason to stay any longer in this place, upon which the American soldiers were marching in an exposed order. The location lay about 5 kilometres from the coast, and the Americans had covered about half of the distance. I hurried to return to the regiment on my motorcycle; I met the tip of my regiment on a large street towards Cherbourg in a village called Saint-Côme-du-Mont. There I gave my first combat orders.”

Von der Heydte ascertained with disappointment that the army unit stationed in Ste.-Marie-du-Mont had cleared out, down to the last man, and were unable to be found. Only the W5 strongpoint, supported by the Marcouf coastal battery, offered ironclad counterfire on the coast. Nevertheless, the Americans succeeded in landing on “Utah” Beach relatively unharmed; they even managed to unload their first tanks. These actions showed that in this portion of Normandy only FJR 6 was in a position to offer serious resistance against the enemy. The regiment’s lack of motorization proved to be a major handicap in this hour, because in order to put the “Utah” sector under massive pressure, it would have required the combat power of the whole regiment.

Defending Ste.-Marie-du-Mont

Both American elite divisions had landed scattered in the area for which the neighboring 709th Infantry Division and 91st Airborne Division were responsible. They were still able to take the strategically important point Ste.-Mère-église and establish it as a firing basis without too much opposition from German anti-aircraft units. At this point, though, Major von der Heydte could not have known that because the radio connection to the neighboring units was inconsistent at best and there was no communication whatsoever for the purpose of coordination.

Near St.-Côme-du-Mont, Major von der Heydte encountered the 4th and 8th Batteries of 191st Artillery Regiment, the 3rd Battalion of the 1058th Grenadier Regiment, and the 3rd Battery of 243rd Anti-Aircraft Regiment; without hesitation, he took these units under his command. Both units had been defeated in battle by enemy troops and had abandoned their positions. The ammunition situation was also inadequate; the infantrymen as well as the artillery had to be supplied from the reserves of FJR 6. Over the radio, von der Heydte was promised the forces of the 635th Eastern Battalion as soon as possible, but their exact time of arrival remained uncertain, and it was hard to estimate what kind of combat power the battalion had.

First Battalion of FJR 6 met with Major von der Heydte in St.-Côme-du-Mont early in the afternoon. From Hauptmann Preikschat, the commander of the battalion, he learned that the 2nd Battalion under Hauptmann Mager was following and should arrive soon in the village; enemy air attacks had separated the two battalions. On the way to St.-Côme-du-Mont, the battalion had exchanged fire with smaller, dispersed groups of American paratroopers. Steadily covering themselves against the enemy both on the ground and from the air was exhausting for the Fallschirmjäger.

Without hesitating long, Major von der Heydte set the 1st Battalion marching towards Ste.-Marie-du-Mont in order to build a defensive wall against the Allied troops marching inland from the coast. As much as possible, it was important to hold the village: “If the enemy pressure became too much, the battalion was ordered to fall back towards the eastern edge of Saint-Côme-du-Mont, while maintaining a delaying fight with the enemy,” von der Heydte remembered.

The infantry battalion took a supporting position by St.-Come-du-Mont; due to the status of their personnel and their equipment, they were no longer in a position to lead an attack. The batteries of the 191st Artillery Regiment were annexed by the 13th Company of FJR 6 in order to deliver counterfire against enemy heavy weapons.

The 2nd Battalion received the order to perform recon on both sides of the large National Road towards Cherbourg, in order to ascertain if the village of Ste.-Mère-église, which was elevated, was still free from enemy troops. In doing so, the battalion’s right flank was supposed to stay in contact with the 1st Battalion as much as possible. Near Turqueville, the battalion had to swing in towards the coast and, together with the 1st Battalion, perform a pincer action to constrict and attack the landing forces at Utah. In order to provide a reserve and to secure the key position of Carentan, the 3rd Battalion remained for now near St.-Côme-du-Mont.

The 1st Battalion moved against Ste.-Marie-du-Mont in a hurried tempo. Hauptmann Preikschat was aware that his battalion for the time being only had itself to rely upon against opponents of unknown strength. Nevertheless, his principal order was to prevent the Americans from building a bridgehead on the coast and, if possible, from uniting with the airborne troops and the neighboring landing zones.

“We Took Hundreds of Prisoners”

Shortly after moving through St.-Côme-du-Mont, Hauptmann Preikschat let his men go into open formation: the 1st and 2nd Companies were on the right of the main road, the 3rd on the left. As they crossed the height of Angoville-au-Plain, the battalion was surprised by the sudden landing of American airborne troops in gliders. Unplanned, the 1st Battalion had arrived at the centre of an Allied airborne operation; they seized initiative, however, and—following the motto “offence is the best defence”—the Fallschirmjäger set upon the Americans and fought their way through their ranks.

Leutnant Eugen Scherer, leader of the 4th Company, describes the situation: “Our battalion’s attack progressed well at first and we rushed immediately into the paratroopers of the 101st Airborne as they landed from military gliders. A gory battle developed on the disorderly grounds. Man against man and group against group. It wasn’t possible for the battalion to have any unified leadership, as new enemy units, which we had to fight, kept landing in the middle of the battalion’s actions.

“We took hundreds of prisoners from the 501st and 506th Airborne Regiments and sent them to our rear, unarmed, with only one or two men to accompany them, because we assumed, as the regimental commander had promised us, that German soldiers would be following up behind us.

“Unfortunately, we lost time because of this battle and could no longer reach Ste.-Marie-du-Mont by nightfall. Also, even though battle noise could be heard from this direction, we could no longer establish communications with 2nd Battalion/FJR 6 near Ste.-Mère-église, who were under fire.”

Unhappy with their results so far, the battalion formed an all-around defence in an open field for the night. As darkness came, the 1st Battalion then lost the support of the 4th Battery of the 191st Artillery Regiment: a fire ambush of American naval artillery on the battery position led to the loss of 27 men, and caused the battery officers to issue an order to abandon the position.

The 1st Battalion also came under heavy fire from naval artillery. In the course of the night, more enemy gliders touched down in the middle of the 1st Battalion, these aircraft carrying supplies for the American paratroopers.

“Save Yourselves If You Can!”

From prisoners, Hauptmann Preikschat learned that other, powerful airborne forces in military gliders had landed in the area of Ste.-Marie-du-Mont. Almost at the same time, a recon troop brought news back that Ste.-Marie-du-Mont was occupied by enemy tanks. The men deployed there, the 3rd Company of the 1058th Grenadier Regiment, were defeated and in scattered formation had to pull back to St.-Côme-du-Mont.

Given these facts, Hauptmann Preikschat decided on the morning of June 7 to pull the battalion back to St.-Côme-du-Mont, as recommended, and to prepare themselves to defend there. During their rapid crossing of the area around Vierville, the battalion ran into an American ambush that broke up and to some extent scattered the unit. The Fallschirmjäger companies engaged in a firefight in order to clear a path for their own forces.

Because the American tanks from Ste.-Marie-du-Mont also joined in the attack, and further American reinforcements closed the ring around the 1st Battalion, casualties increased dramatically until finally Preikschat gave the order to “Save yourselves if you can!” The 4th Company, under Leutnant Scherer, supported by Leutnant Krüger’s antitank weapons, tried to hold back the U.S. tanks.

In small groups, the Fallschirmjäger tried to break out of the encircled area below the castle of Vierville and to withdraw towards the locks of La Barquette. The flooded areas, which had been created to hinder the Allied airborne landings, thwarted them in this plan, as the enemy now used the swamps to their advantage.

South of Angoville-au-Plain, as they waded through the reedy marsh, the Fallschirmjäger were attacked anew by strong American units. The Germans suffered heavy casualties–during the night, more American airborne soldiers had landed in this area via parachute and 150 military gliders, and they now occupied the area.

The Fallschirmjäger tried, at the edge of the swamp or while standing in mud up to their chests, to fight through the ring of Americans to the southwest. The result was further close combat with the American paratroopers, which cost the remains of the 1st Battalion bitter losses. Only a few hundred meters away from their own positions, the Fallschirmjäger were gunned down by Americans lying in ambush near La Barquette.

The men of the 1st Battalion made some gruesome observations, as Jäger [Luftwaffe Private] Manfred Vogt of the 4th Company remembers: “In the chaos, I had lost my weapon, and I lay with an older Obergefreiter under a hedge for cover. At the edge of the swamp we observed how a few Americans gave one of our wounded a good once-over. With fists and the butts of their weapons they beat the poor guy and kicked him with their boots. When he could no longer move, one of the Americans put his foot on the guy’s head and pushed him into the water until he drowned. So those were the ‘Sing-Sing’ [a New York prison infamous for the brutality of it guards] methods of the American paratroopers.”

“Dead Man’s Corner”

During the night, the staff doctor, Dr. Roos, the leading medical practitioner of the regiment, tried to break through in a Kübelwagen to the 1st Battalion under the protection of the Red Cross, in order to offer medical relief. He did not make it—Roos fell into an American ambush and was shot. Some Fallschirmjäger found him dead in his Kübelwagen near the church of Ste.-Marie-du-Mont.

Oberleutnant Wilhelm Billion, leader of the 1st Company, called to his men: “Either we get out of here or we get captured. But that is not an option for us!” A few minutes later, he fell from a bullet to the head.

Some members of the 3rd Company withdrew towards the direction of their own troops, and occupied a small street and the houses around it. An American tank unit tried to proceed down the street and break through the Fallschirmjäger positions, but was prevented by the concentrated fire of the Panzerfausts. A U.S. Stuart tank was stopped in the middle of the crossing and went up in flames. The commander, standing in the turret hatch, did not manage to escape the tank, and he burned to death at his post. He unwittingly gave the crossing its name: “Dead Man’s Corner.”

Obergefreiter Karl-Heinz Mayer, at the time in the 3rd Company, was wounded in the action by an American sniper: “The Americans had posted sharpshooters [snipers] in the trees. Even when one of them was hit, he did not fall down, because these boys had belted themselves in.

“I was a machine-gunner. A sharpshooter hit me in the face, in the left cheek. The bullet dug its way through my collarbone into my right breast. He probably wanted a clean shot to the head, but the smallest movement on my part probably saved my life. I crawled into the gutter by a house on the corner.

“I don’t know how long I lay there, but at some point American soldiers stood in front of me. They yelled at me to stand up. One of them kicked me a few times in the side because he wanted to get at my gravity knife. I just wanted some water, but they didn’t understand me. One of them threw me some chocolate, then he realized how badly wounded I was and gave me something to drink. The war was over for me.”

On the evening of June 7, Hauptmann Preikschat’s men, most of them wounded and unable to fight, accepted the offer of surrender from Colonel Johnson of the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment [sic—the 506th’s commander was Colonel Robert Sink]. Preikschat’s battalion had lost over half its men since the retreat towards Vierville. Only 25 men under the leadership of Leutnant Stenzel managed to escape from the enemy and fight their way back to their own lines. On the evening of June 10, the only thing they had to report to Major von der Heydte was the destruction of the brave 1st Battalion.

Their comrades expected execution at the time. According to the order of the American general Maxwell Taylor, during the first days of the invasion no German prisoners were to be taken, so the American paratroopers prepared to execute the survivors of the 1st Battalion. Only the selfless interference of an American captain, who had been taken prisoner by the German Fallschirmjäger the night before and had been well treated by them, saved Preikschat’s men from death.

The American Mortars at Ste.-Mère-église

While the 1st Battalion moved against the enemy, Major von der Heydte had established radio connection with the neighboring German forces. From the 709th Infantry Division, he learned that they were preparing an offensive in Montebourg on the morning of June 7. Therefore, the 2nd Battalion under Hauptmann Mager departed right away; they received the order to go around Ste-Mère-église via Tourqueville and move against the Utah landing zone and, in an extension of the 1st Battalion’s position by Ste.-Marie-du-Mont, seal off the beach section. With the U.S. paratroopers cut off from their amphibious reinforcements, it would be possible to take the American airborne troops in a pincer move.

In the meantime, the 3rd Battalion was supposed to put pressure on and destroy the remains of the American paratroopers who had landed during the night. Scouts from FJR 6 reported that enemy groups had entrenched themselves in the villages of Graignes and Tribehou. Because these units could threaten the regiment’s rear, the 3rd Battalion advanced against them; only the 9th Company was directly assigned to secure Carentan.

The occupation of Tribehou occurred without great difficulties, but a sudden radio report to the regimental command post stopped the operation: American recon troops had been spotted near Carentan and the 3rd Battalion received the order to return as soon as possible to the city. While the battalion was marching back, the 9th Company reported that the Americans for now had pulled back in the face of the greater numbers of the German troops. At 9:00 pm the battalion took position, and the city was secured.

The early phase of 2nd Battalion’s operation was proving difficult. Because of heavy Allied air attacks, progress was slower than planned and they were forced to spread out widely. The open area south of Ste.-Mère-église facilitated quick progress, but Hauptmann Mager’s runners were unable to establish contact with the 1st Battalion. To top it all off, troops from the 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment had dug themselves in here and directed heavy field artillery fire at the 2nd Battalion.

The Fallschirmjäger managed to advance to Turqueville and fall into position here, when they came under shelling from both directions: from St-Mère-Eglise came mortar fire, while from the ocean they were battered by huge naval artillery shells the size of boulders.

Nevertheless, Mager tried to complete his assignment, and Eugen Griesser received new orders: “Our battalion was supposed to offer flanking protection to the 1st Battalion, who advanced on Ste.-Marie-du-Mont against the American paratroopers, whom we suspected were northwest of us. Suddenly, we were under heavy fire from Ste.-Mère-église. Hauptmann Mager had no radio connection with the anti-aircraft division that was supposed to be in this location, so he put together two recon troops. ‘You do this!’ he said to me.

“We left everything that rattled and clanged with the platoon HQ and went stalking. Our approach lasted longer than suspected, because we were partially moving across open ground, which we had to do quite carefully, and because we had to go around some forward-deployed American posts. Coming from the location [Ste.-Mère-église], we already heard the firing sounds of American mortars.

“The fact that no combat noise could be heard in the area meant that the anti-aircraft units had either been destroyed, or that they had cleared out of their positions. But we had no idea how strong the enemy in Ste.-Mère-église was. Best-case scenario: only a heavy company with their howitzers; worst-case scenario: hundreds of Americans and more.

“We managed to push forward into the heart of the objective and one thing quickly became clear: Ste.-Mère-église was occupied by at least one battalion. Until then, we hadn’t seen any vehicles, but our chief would be unable to ignore a battalion with mortars on our flank.

“Suddenly, from a window two meters to the left of me, a submachine gun started firing, and from the other side of the square machine guns clattered. But they were not aiming at us; the fire was directed at a second recon troop somewhere to our right. We stood in the blind spot of the shooters in the window, and had not yet been discovered. Gerd Kerl and I pulled out our hand grenades and tossed them into the window. The firing from the window stopped right away. I shot off a few bursts of gunfire from my submachine gun, to be sure, and looked into the room; apparently we had blasted a radio station.

“Now one of the machine guns from the church tower was shooting at us, so it became time to return to the battalion. We ran along the alley, as fast as our feet could carry us, and I believe we could have broken any world record in this moment. An American emerged from behind a house corner, planted himself in our path, lifted his rifle and yelled something at us in English. We just ran over him; we couldn’t have stopped anyway, we were running that fast.

“Once clear, we just threw ourselves behind a hedge, in order to catch our breath; then we slipped back to the battalion. After we had made our report, we just had enough time to pick up our things from the company troop and drink a sip of cold coffee, then our first attack on Ste.-Mère-église began.”

In Part II, FJR 6 fights furiously for its life in and around Ste.-Mère-église in a desperate attempt to wipe out the American paratroopers. You can find Part III here.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments