By Arnold Blumberg

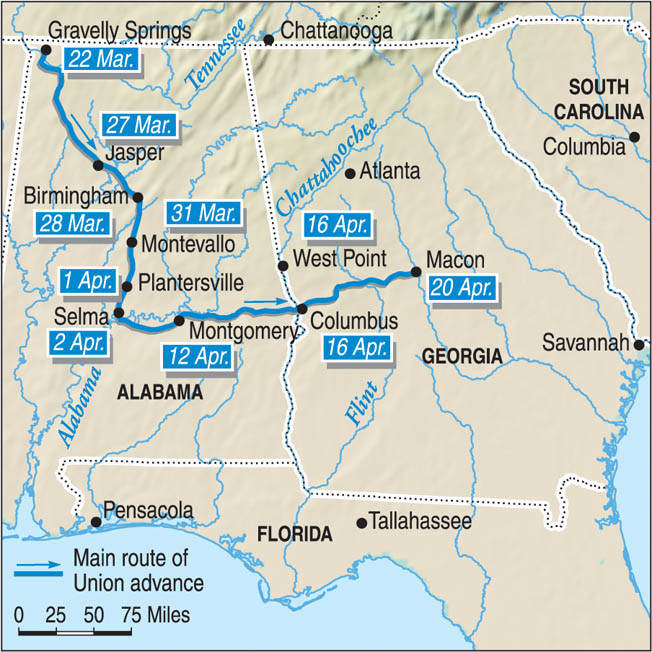

As reveille sounded through the Union encampments on the south bank of the Tennessee River between Eastport, Mississippi, and Chickasaw, Alabama, on March 22, 1865, sleepy Federal troopers roused themselves, built fires, and cooked breakfast. When the chilly gray dawn broke, “Boots and Saddles” rang out and nearly 14,000 cavalrymen formed up and turned southward toward the heart of Alabama. An officer at the scene later remembered, “Never can I forget the brilliant scene, as regiment after regiment filed gaily out of camp, decked in all the paraphernalia of war, with gleaming arms, and guidons given to the wanton breeze.”

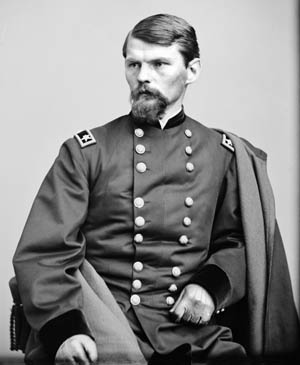

For most of the blue-coated host, the ultimate objective of their movement was a mystery, although a majority would have agreed with the confident assessment of Brig. Gen. Emory Upton, who wrote to his sister, “The present campaign, I trust, will seal the doom of the Confederacy. I cannot see how it can be otherwise.” The upcoming campaign would see the largest mounted raid conducted by either side during the Civil War, a daring drive into the very heart of the Confederacy.

James Wilson’s Raiders

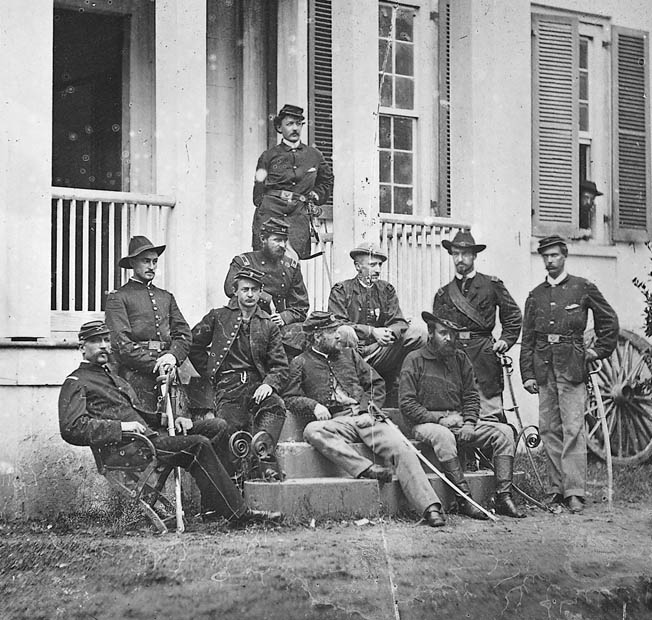

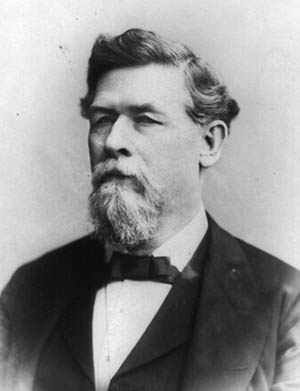

Leading the raid was 27-year-old Maj. Gen. James H. Wilson, a protégé of Union commander Ulysses S. Grant. On February 23, Wilson’s immediate superior, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas, came to Gravelly Springs, Alabama, on the north shore of the Tennessee River to review Wilson’s 17,000-strong corps and to discuss future operations in central Alabama. Thomas endorsed Wilson’s overall goal for the raid: the defeat of the Confederate defending forces under Lt. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest, the capture of Tuscaloosa, Selma, Montgomery, and Columbus, and the destruction of the last functioning manufacturing, supply depots and railroads in the region. At Thomas’s urging, Grant also gave his approval to Wilson’s concept, allowing the young cavalry commander “the amplest discretion as an independent commander.”

With the necessary approval in hand, Wilson marshaled the force he would lead into Alabama. By this time, the cavalry corps of the Military Division of the Mississippi, numbering between 22,000 and 27,000 men, had been steadily reduced by a series of detachments. Four full divisions originally under Wilson’s authority had been lost. Brig. Gen. Hugh Judson

Kilpatrick’s 3rd Cavalry Division rode with Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman on his March to the Sea, while Brig. Gen. Richard W. Johnson, at the helm of the 6th Cavalry Division, was kept in reserve in middle Tennessee.

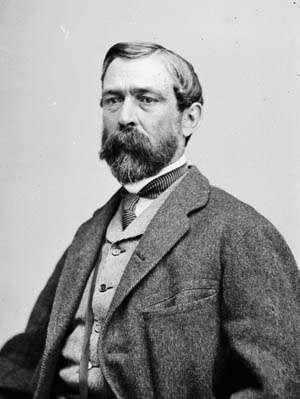

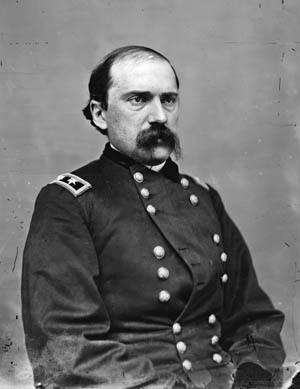

In early February, Wilson was ordered to send another 5,000 troopers to join Maj. Gen. E.S. Canby’s overland campaign against Mobile. Wilson picked Brig. Gen. Joseph F. Knipe and the 7th Division to join Canby. Additionally, Brig. Gen. Edward Hatch’s 5th Division had to be removed from the list of formations going with Wilson into Alabama for lack of horses. This left only three divisions in the proper state of readiness to march south with Wilson: the 1st, 2nd, and 4th Cavalry Divisions, commanded respectively by Brig. Gens. Edward M. McCook, Eli Long and Emory Upton.

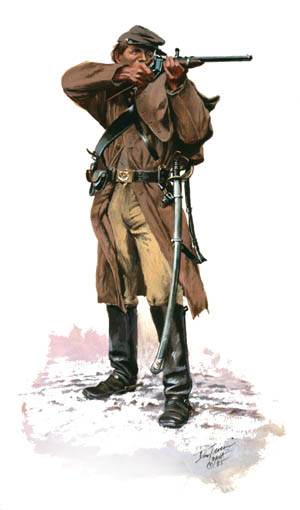

The three divisions, each comprised of two brigades and an artillery battery, numbered 13,480 men among them, of whom 11,980 were mounted and 1,500 dismounted. The latter group was detailed to guard the expedition’s 250 wagons, which included 50 conveyances carrying 30 pontoon boats, 45 days of rations and ammunition, and a pack mule train loaded with another five days of rations. Almost all Wilson’s troopers carried seven-shot Spencer breech-loading carbines. McCook commanded 4,096 men, Long 5,127, and Upton 3,923. The 4th U.S. Regular Cavalry Regiment under Lieutenant William O’Connell provided a 334-man personal escort for Wilson and his staff.

The Stalled Campaign

Wilson envisioned a 60-day campaign, assuming that additional supplies could be obtained by foraging off the land. The cavalry commander hurriedly completed last-minute training and equipping of his soldiers and prepared to cross the Tennessee River and head south on March 5. Unfortunately for the eager Wilson and his men, a deluge of rain made the Tennessee River an impassable torrent and turned the roads into ribbons of mud. “The oldest inhabitant has seldom seen heavier rain,” recorded the Clarke County Journal of Grove Hill, Alabama. Two weeks later it reported that the Alabama River was at its highest level in 40 years.

Stymied by the sodden ground and the flooded river, Wilson’s entire corps had to wait on the northern bank of the Tennessee River until the rain subsided and the waters slowly receded. For three days, from March 14 to 17, the horsemen were finally ferried across. Hoping to start his grand enterprise on March 20, Wilson was further delayed by the loss of vital animal forage being brought up by boat. Informed that the first 120 miles of his proposed march would be over country barren and devoid of sustenance for his mounts, Wilson had to wait for replacement forage to reach him.

Facing Forrest’s Forces

While biding his time, Wilson sought to gain information about the roads, river crossings, and enemy forces he would face in Alabama. He knew that most of the Confederate infantry had gone to North Carolina to face the threat of Sherman’s March to the Sea. As a result, Wilson assumed that he would be facing mainly cavalry, militia, and home guards in central Mississippi, Alabama, and Georgia. The quality of the militia and home guards did not alarm him, but the vaunted horse soldiers under Nathan Bedford Forrest could never be underestimated.

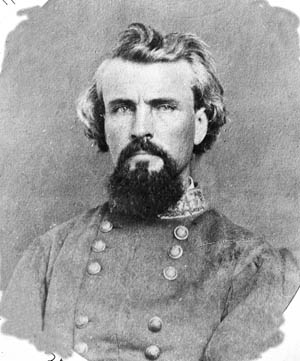

By early March, Forrest was headquartered at West Point, Mississippi, commanding all the mounted Confederate troops in East Louisiana, Mississippi, and Alabama. His main concern at the time was to reorganize his forces after the defeats sustained late the previous year. The Tennessee troops of Brig. Gens. Tyree H. Bell and Edmund Rucker, along with Brig. Gen. Lawrence S. Ross’s Texans, were placed in one division under Brig. Gen. William H. “Red” Jackson. The Mississippians of Brig. Gens. Frank C. Armstrong, William W. Adams, and Peter B. Starke comprised a second division headed by Brig. Gen. James R. Chalmers. Brig. Gen. Abraham Buford’s Kentucky brigade was assigned to serve with Brig. Gen. Dan W. Adams’s militia forces in the District of Alabama. Rounding out his command, which on paper numbered barely 9,000 troopers, of whom only about 7,500 were properly mounted, equipped, and organized for immediate field service, was Colonel Robert “Black Bob” McCulloch’s 2nd Missouri Regiment, acting as Forrest’s personal escort. Forrest’s artillery arm was provided by Captain John W. Morton’s veteran Horse Artillery Battalion.

Reports by Forrest’s scouts indicated that the heavy concentrations of Union troops along the Gulf region and Tennessee River portended a strike against the interior of Alabama, with the port city of Mobile and the arsenals and machine shops of Selma and Tuscaloosa as their main objectives. Concluding that Wilson was the greatest threat, Forrest in mid-March ordered Chalmers to Selma. On March 25, after belatedly learning that Wilson’s force was on its way, Forrest sent Jackson’s command to Tuscaloosa to strike the Federals in flank. Forrest’s commanding officer, Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, disagreed, deciding that the most immediate threat came from the Canby. Concluding that Wilson’s command would be easier to repel, Taylor wrote Forrest on March 26 that Jackson’s division would be enough to “whip and get rid of that column as soon as possible.”

Taylor’s and Forrest’s intelligence-gathering efforts failed to reveal the true strength of the Union expedition heading into Alabama. Moreover, Forrest’s failure to detect Wilson’s departure for three days proved vital to future Confederate efforts to thwart Wilson’s raid. Had Forrest been able to move promptly and intercept Wilson early on, particularly in the rugged, easily defensible country of northern Alabama, he might well have delayed or even turned back the Federals. As it was, with Wilson three days out and Forrest still at West Point, 150 miles from Eastport, the only organized Confederate force that could confront Wilson’s was Brig. Gen. Philip Roddey’s command, lurking 35 miles north of Selma.

Wilson’s Three Columns

As Forrest pondered his enemy’s objectives and how to counter them, Wilson and his legions had already commenced their 250-mile trek from Gravelly Springs to Selma. Fully aware of the threat Forrest posed to his mission, the young Union cavalry chief, in a effort to confuse his celebrated opponent, divided his command into three columns: McCook’s division on the right, Long’s in the center, and Upton’s taking the left. The marching formation carried real risks for the Federals because the broken and hilly terrain of northern and central Alabama would make it very difficult for the three Union columns to give timely support to one another in case they were attacked.

Wilson’s decision to spread his men over the Alabama landscape was also dictated by the fact that his men and horses would have to live off land already destitute of supplies for over 100 miles before they reached the more bountiful resources of the state’s south-central region. Wilson hoped that dispersing his formations would allow them to travel at least 30 miles a day. “As celerity of movement is of the most valuable force in modern military operations,” he said, “that force which moves most rapidly can place itself in the best position for effective service.” No doubt Forrest, author of the famous dictum “Get there first with the most men,” would have wholeheartedly agreed.

In addition to negotiating the hilly terrain, the Federals had to cross three major waterways en route to Selma: the Mulberry and Locust forks of the Black Warrior River situated between Jasper and Elyton, and the Cahaba River south of Elyton. These rivers, with their hard-to-negotiate rocky beds, were even more serious obstacles after the heavy rains the previous month had created swift currents and overflown banks on all three rivers.

Wilson reached Jasper on the 27th after contending with rough ground, swollen streams, and roads turned into “a mass of ruts” due to the recent heavy rains. The roads were in such terrible condition that John Croxton, one of Wilson’s brigade commanders, was compelled to cut new roads, corduroy old ones, and build temporary bridges over swamps. At Jasper, Wilson was informed that enemy cavalry (part of Chalmers’s division) was leaving Mississippi and concentrating at Tuscaloosa and Selma. Accordingly, he determined to move farther south as quickly as possible in order not to be held up by the enemy north of the Black Warrior and Cahaba Rivers. To allow for more rapid progress, he left his large wagon train north of the Black Warrior River, relying on pack mules to carry supplies.

Forrest Discovers Upton’s Men

On the 27th the Union mounted corps passed over the Mulberry Fork; on the 28th they traveled the eight miles to Locust Fork and crossed. The next day Upton’s men entered Elyton (now Birmingham), a distance of 125 miles from their starting point at Gravelly Springs, and were joined by McCook and Long the next day. Between Elyton, a town of 3,000, and the Cahaba River, a substantial iron industry had grown up during the war. Upton’s men did a thorough job of eliminating the manufacturing and production infrastructure, destroying the Red Mountain, McIlvain, Bibb, and Columbiana Iron Works, the Cahaba Rolling Mills, and five collieries. Sergeant Benjamin McGee of the 72nd Indiana Mounted Infantry, remembered the scene of devastation perpetrated in the region, noting that “the sky was red for miles around caused by fires burning cotton gins, mills, factories.”

Pushing south from Elyton, Upton’s brigades headed for Montevallo, the center of coal and iron production in central Alabama, 60 miles north of Selma. With the main crossing of the Cahaba River blocked by enemy-placed obstructions, an alternate route across had to be found. Union engineers converted an eight-foot-wide, 300-yard-long footbridge over an undamaged trestle of the Tennessee & Alabama Railroad that crossed the river near Hillsborough. Once over the river, Upton’s division reached Montevallo in the late evening of March 30.

By the time the Federal cavalry had reached Elyton, Forrest was aware of their presence. On March 25 he ordered Jackson’s division, later joined by Colonel Edwin Crossland’s Kentucky brigade (a total of around 3,500 men), to proceed to Tuscaloosa. Three days later Taylor wired Forrest that “Adams reports enemy encamped at Jasper on night of March 26, three divisions under Wilson, with artillery; destination Elyton and Montevallo.” Taylor concluded his message with the hope that Roddey’s 1,000 men could slow the Union advance until Forrest’s reinforcements arrived on the scene. After receiving Taylor’s message, Forrest left West Point heading for Montevallo via Tuscaloosa. Along the way he passed Jackson’s command and ordered it to proceed to Centerville, Alabama, 40 miles southwest of Selma, and hold the bridge over the flooded Cahaba. That same day Chalmers, with perhaps 3,000 troopers, reversed course and headed for Selma.

The Clash at Montevallo

As the Confederate forces positioned themselves to confront the enemy, Wilson prepared to depart Elyton and join Upton at Montevallo, 20 miles from Selma. Before doing so he detached Croxton’s brigade, 1,500 strong, to capture Tuscaloosa 50 miles to the southwest. Destroying the important rail and manufacturing center there would not only take out a vital enemy communications link, but also shield the Federals’ right flank as they moved deeper into Alabama.

At 1 pm on the 31st Wilson joined Upton at Montevallo, where a small rear guard of Roddey’s force had been driven out, and ordered Upton to resume the advance. With Kentucky Brig. Gen. Andrew J. Alexander’s 2nd Brigade in the lead, Upton pushed down the Randolph Road toward Selma, where he came across the enemy. Two miles south of town Roddey had set up a skirmish line along a ridge, hoping to delay the Union advance until reinforcements from central Alabama could congregate. As Alexander’s unit approached the Southern position, his lead element, the 5th Iowa Cavalry, sliced through the Confederate position. Their success was exploited by Brig. Gen. Edward Winslow’s 1st Brigade. As Roddey’s men streamed down the Randolph Road, they conducted a number of delaying actions. After being reinforced by 500 men under Crossland and Adams, Roddey was able to form a new line along Six-Mile Creek, three miles south of Montevallo.

As the Federals approached the creek, Crossland counterattacked and forced them back. Crossland in turn was hit by the 3rd Iowa Cavalry. Soon, the 4th U.S. Artillery arrived and began shelling the Confederates. The 10th Missouri, 3rd and 5th Iowa then attacked, breaking the enemy resistance. The Confederates, in disorder, raced southward toward Randolph. Darkness ended the Union pursuit, and Upton’s men camped 14 miles south of Montevallo that night, while McCook and Long continued moving south from Montevallo. In the running, 14-mile fight, the bluecoats had sustained 50 casualties, while the Confederates lost twice that number.

Intercepting Forrest’s Message to Jackson

While Roddey and Crossland battled Upton, Croxton headed south for Tuscaloosa, where he discovered that he was near Jackson’s division, which was hurrying east to join Forrest. Croxton interposed himself between Jackson’s cavalry and his artillery and wagon trains at the village of Trion. With the enemy in his rear, Jackson turned about to encircle and assault his unsuspecting prey. Croxton, alerted to Jackson’s maneuver, moved westward on Mud Creek Road. As the Federals moved out, Jackson struck, overrunning the Union camp and pursuing them for several miles. The Union retreat soon turned into a rout, but the bulk of Croxton’s men managed to escape in the gathering dark.

Wilson still had the upper hand over his opponent; a stroke of luck on April 1 would add to his already considerable advantage. Captured messages from Forrest to Jackson detailed Rebel dispositions around Selma. Intending to keep Forrest and Jackson apart, Wilson dispatched McCook and the 2nd Brigade under Colonel Oscar H. LaGrange to secure the bridge spanning the Cahaba River at Centerville, 10 miles west. The bridge was the only crossing point over the Cahaba north of Selma. McCook was also to attack Jackson’s force and link up with Croxton.

McCook’s forces captured the bridge that same day. Looking in vain for Croxton, McCook attacked Tyree Bell’s Confederates defending a barricade near Scottsville. Hurled back by the enemy, McCook recrossed the Cahaba and rejoined Wilson’s main force. Once across the river, the Federals set fire to the bridge. They also destroyed or removed all the boats in the vicinity. Although McCook had been defeated in the short, sharp action, his efforts ensured that Jackson would not unite with Forrest.

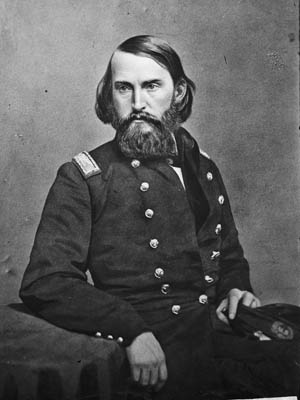

While McCook rode for the Centerville Bridge, Wilson instructed Upton and Long to push Forrest toward Selma “with the utmost spirit and rapidity.” The two Union divisions advanced to Ebenezer Church, six miles north of Plantersville, where Forrest had chosen to make a stand along the north bank of Bolger’s Creek. The Confederate right rested on Mulberry Creek and was held by a battalion of Adams’s untried Alabama state troops. Roddey’s forces held the center, with a pair of guns posted to cover the Old Maplesville Road over which Upton was approaching. Crossland’s Kentuckians manned the left on a high wooded ridge, supported by four pieces of artillery sited to sweep the Randolph Road. To strengthen his position further, the Confederate commander had his men erect rail barricades. As Forrest deployed his men, Armstrong’s brigade reached him. However, the balance of Chalmers’s men did not arrive due to flooded roads and conflicting orders. The result was that Forrest had no more than 2,000 men at Ebenezer Church against Wilson’s 9,000 troopers.

Making Camp at Plantersville

As dawn broke, Upton got his command moving a few miles east of the Randolph-Plantersville Road, while Long marched south on the thoroughfare. Acting as the vanguard of Long’s division was the 72nd Indiana Mounted Infantry, part of Brig. Gen. John T. Wilder’s famous Lighting Brigade, which first encountered the enemy four miles below Randolph. The Hoosiers commenced a running gunfight with Confederate forces that lasted the entire morning and well into the afternoon, with the graybacks leapfrogging from one defensive position to another before stopping at Bolger’s Creek.

At 4 pm Long’s troopers came up against a Confederate skirmish line near Ebenezer Church. The 72nd dismounted and, employing withering fire with their seven-shot repeaters, drove the skirmishers back into Forrest’s position. Unaware that he had reached the enemy’s main line of resistance, Long sent four companies of the 17th Indiana Cavalry charging into the Rebel works along the creek. A furious mounted melee ensued. One desperate hand-to-hand encounter pitted Forrest against Union Captain James D. Taylor. Forrest, a much-experienced fighter, suffered a saber wound to the arm, his fourth during the war, but fatally shot Taylor from his saddle. Overwhelmed by sheer numbers, the 17th Indiana retreated after losing 17 men.

As the 17th Indiana fled, Long threw Colonel Abram Miller’s brigade into the fight. Miller dismounted his men and moved toward the Confederate position. As he did so, Andrew Alexander’s brigade of Upton’s division, hearing the firing to their right, came to Long’s assistance. Charging through a clearing, Alexander struck the Confederate right held by Forrest’s most unreliable men: Adams’s state militia troops. As Adams’s men crumbled under the Federal pressure, the experienced cavalry came to their aid and prevented a complete rout. The Confederate reprieve was short-lived. As the Southern forces slowly fell back, Edward Winslow’s 3rd and 4th Iowa Cavalry launched a mounted assault in support of Alexander. Unable to withstand the combined enemy infantry and cavalry attack, the entire Confederate right disintegrated. Forrest’s center and left, now outflanked, soon fled across Bolger’s Creek heading for Plantersville and Selma.

As his enemy ran for safety, Wilson took stock of his victory at Ebenezer Church. It amounted to 200 prisoners and three pieces of artillery. The number of Confederate dead was not recorded. The price the Federals paid for their triumph was 12 dead and 40 wounded. Wilson’s corps camped that night at Plantersville, 19 miles from Selma.

The Defenses at Selma

At 6 am on April 2, Wilson’s blue juggernaut saddled up and moved from its camps toward their principal objective: Alabama’s premiere industrial city, Selma. The industrial center stood on a bluff overlooking the north bank of the Alabama River. North of the city the country was relatively flat, and it was from this direction that Selma was most vulnerable. Of the six major roads entering the town, four crossed the plain. Two railroads, the Alabama & Tennessee and the Alabama & Mississippi, served the city. The Alabama River, bordering the city’s southern margin, also functioned as another vital commercial and communication artery.

Selma, the seat of Dallas County, employed 10,000 workers in its various factories. The city housed a huge arsenal of 24 buildings that produced artillery pieces, field carriages, artillery ammunition, and uniforms. Its naval foundry not only manufactured cannons and small arms, but also armor plate for Confederate gunboats. Besides government facilities, the city also housed private enterprises such as the Selma Iron Works, which could produce 30 tons of iron a day. The Powder Mill and Magazine created thousands of rounds of musket and artillery rounds. In addition, 10 other privately owned foundries and iron works inside the city churned out arms and ammunition for the Confederate Army. During the last two years of the war, half the artillery pieces and two-thirds of all fixed ammunition used by the South came from Selma. Along with weapons, the city’s factories produced all sorts of soldier kit and horse equipment. It was also a major production and repair center for locomotives and rolling stock, as well as a main food distribution point from the fertile Alabama black belt.

Defensive works had been constructed at Selma two years earlier. The main defense perimeter formed a semicircle around the town, starting in the west near the junction of the Alabama River and Valley Creek and meandering northward. Crossing the Marion-Cahaba Road and the Alabama & Mississippi Railroad, the works included a line of stockade rifle pits, with four forts paralleling the Summerfield Road. At the point where the line veered north, crossing the Summerville Road and the Range Line Road, was a strong parapet line six to eight feet tall and eight feet thick at the base. Fronting the parapet was a water-filled ditch five feet deep and five feet wide.

East of the Range Line Road, the stockade rifle pits began again, angling to the southeast across the Alabama & Tennessee Railroad and the road to Burnsville and anchoring at the Alabama River just east of Selma. Fields in front of all the defensive positions had been cleared to allow good fields of fire. Swampy terrain north of town offered additional natural protection. To the south, the broad Alabama River protected Selma. The main defense line was close to the city on the east and west sides and 1½ miles away on the north.

The weak point in the five-mile defense line was to the north over rolling, clear ground devoid of natural features. For that reason the strongest segment of the defensive position was sited at that quarter. As formidable as Selma’s fortifications appeared, they would do little good if not properly manned, and Forrest did not have the soldiers to do that. He had about 3,000 troops and 32 guns. Chalmers’s division, minus Armstrong’s brigade, which had joined Forrest earlier, would never get to Selma due to the impassable swamplands it had to travel through along the Cahaba River. He simply did not have enough men to garrison all the defensive works against a foe who outnumbered the defenders three-to-one.

“Go in Boys, Give Them Hell, We Have the City!”

Around noon Forrest met with department commander, Richard Taylor, and before the latter left the city assured him Forrest would do all in his power to defend the city. By 2 pm Forrest’s men were filing in to its defensives; at the same time, Union scouts were riding over the plain to the north getting their first glimpses of those defenses.

As the Union cavalry neared Selma on April 2, its officers and men were confident they would capture the place. That confidence had been bolstered by information provided by an Englishmen named Millington, a civil engineer who had been working on the Selma defenses. Millington related all he knew about Selma’s fortifications thus immeasurably aiding Wilson’s plan of attack on the town. That scheme, the first assault on a fortified urban center delivered by Wilson’s command, would take the form of a night strike with Long moving from the northwest diagonally across the Summerville Road. Meanwhile, Upton would advance from the north along the Range Line Road and pass through a swampy area east of the city. In addition, a battalion of the 4th U.S. Regulars was to follow the Alabama & Mississippi Railroad as far as Burnsville, burning bridges and stations.

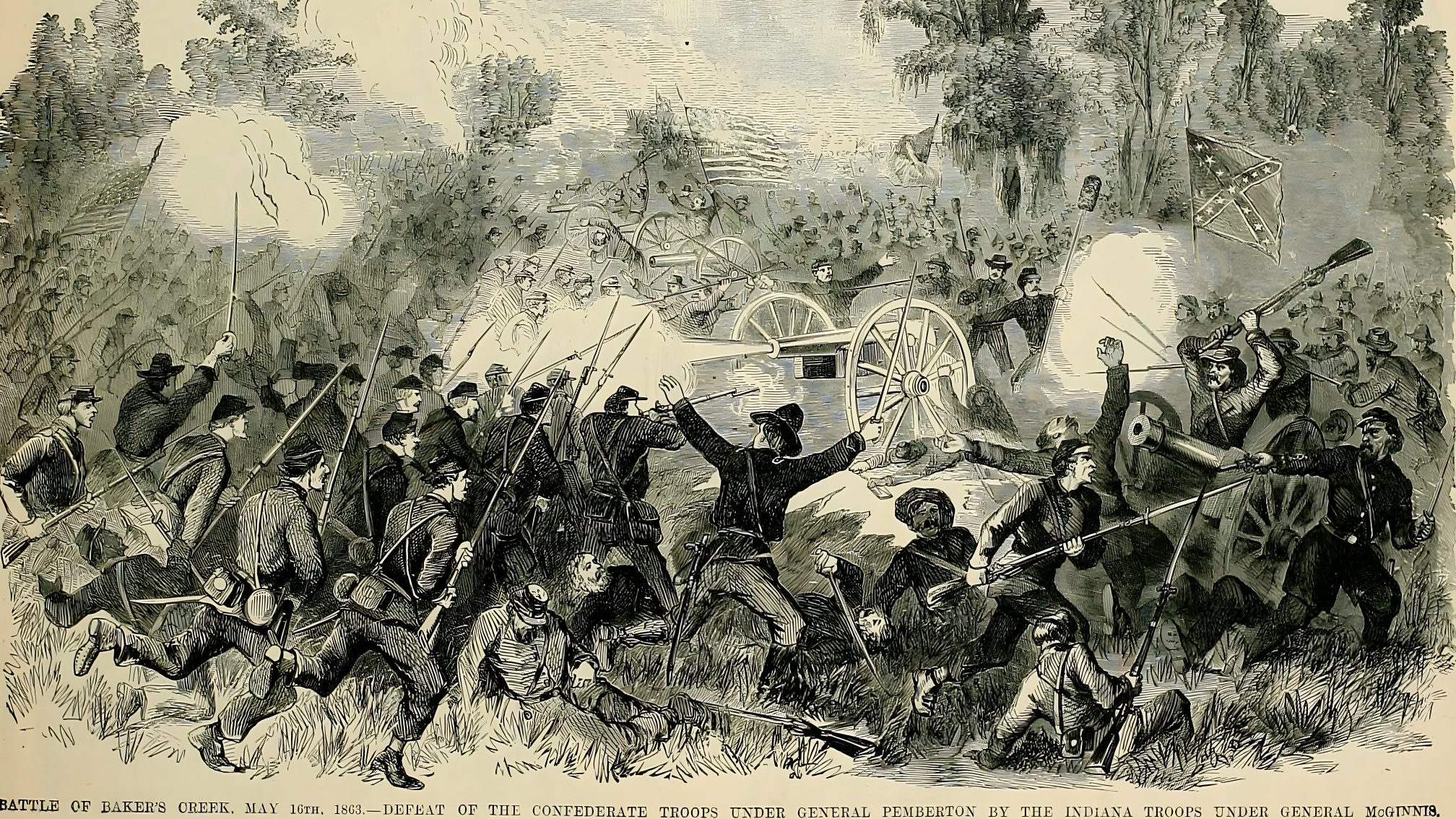

By 4 pm Long and Upton, having traveled along their assigned routes, were close to Selma’s outer defense line. Long, concerned that the close presence of some of Chalmers’s troops might disrupt the planned attack, initiated the first strike on Selma before the official start signal sounded at 4:30. From a half mile out, 1,500 men of the 2nd Division, firing their Spencers as they went, charged Selma’s outer defenses on foot. They were met by a savage volume of fire from the defender’s cannons and small arms. Reaching the stockade, the Federals entered the works, facing defenders fighting with clubbed muskets and fists, and forced back the Confederates. It took only 25 minutes to breach the enemy fortifications but the Unionists paid a price: Long was severely wounded in the head, and three colonels and more than 300 men were also wounded.

To Long’s left, Upton’s men soon launched their own attack with Winslow’s boys taking the lead. As the 3rd Iowa and 10th Missouri hot footed it down the Range Line Road, several of their officers yelled, “Go in boys, give them hell, we have the city!” The troops of the 2nd Cavalry Division broke the enemy lines and pushed their adversaries back to a second line of defense. As the outer defenses of Selma crumbled under the weight of the Federal attack, Union horse artillery rushed to the front and poured devastating volleys of canister into the backs of the fleeing rebels. Along with the forward rushing artillery, Wilson, caught up in the thrill of battle, gathered his escort and charged down the Summerville Road at the enemy’s works. Near the Confederate second line of defense Wilson’s horse was shot down, but the general himself was unharmed.

Although the Confederates continued to fight gallantly from their interior defensive line, the pressure from the two Federal divisions ruptured the position, driving the defenders back into the city. “The troops,” Wilson later wrote, “inspired by the wildest enthusiasm, swept everything before them and penetrated the city in all directions.” In the gathering darkness and chaos of battle, Forrest and the remnants of his command escaped east along the Burnsville Road.

Selma Destroyed

As darkness descended, pandemonium reigned within the city. Fires broke out and vandals—both Union soldiers and Southern civilians—plundered the town. Wilson had captured 2,700 prisoners. The number of Confederates killed or wounded was unknown. In return, the Federals lost 46 killed, 300 wounded, and 13 missing. Riding among the jubilant members of the Lighting Brigade, Wilson called out: “Men! I see now how it is that you have gotten such a hell of a name!” Wild cheering answered him.

In the days following the fall of Selma, its Union occupiers went about destroying the place’s value to the Confederate war effort. This included the destruction of the 50 acres of buildings, including the arsenal, iron works, naval foundry, niter and powder works. Three million feet of lumber, locomotives, railcars, and machinery were also consigned to the fires. More than 2,000 horses and mules, as well as their provisions, had fallen into Union hands. One Federal described the destruction: “The scene was hideous and unearthly beyond anything we have ever imagined. The explosions continued for three hours, much louder than any we had ever heard, and of sufficient violence to shake the earth for miles around, making the city a perfect pandemonium.” Anything that could not be burned was thrown into the Alabama River.

A couple of days later Wilson rode to Cahaba under a flag of truce to discuss the exchange of prisoners with Forrest, who sported a dirty bandage on his arm where the late Colonel Taylor had sliced him with his sword. “If that young man had known enough to give me the point of his saber, instead of the edge, I wouldn’t be here today,” Forrest told Wilson phlegmatically. The other cavalryman commiserated. More to the point, Forrest conceded to Wilson, “Well, General, you have beaten me badly, and for the first time I am compelled to make such an acknowledgment.” Wilson allowed that Forrest had put up a stout fight, but the fearsome Confederate was not mollified. He could have captured Wilson’s force twice over, said Forrest, and that would still not have compensated for the loss of Selma. They left it at that. When Governors Charles Clark of Mississippi and Isham Harris of Tennessee pressed Forrest to lead his remnant forces to Texas to continue the fight, Forrest growled, “Men, you may do as you damn please, but I’m a-going home. To make men fight under such circumstances would be nothing but murder. Any man who is in favor of a further prosecution of this war is a fit subject for a lunatic asylum.”

The Battles of Columbus and Fort Tyler

After eliminating Selma as center of Confederate manufacturing and supply, and determining that no enemy forces were east of the Cahaba River, Wilson took his corps out of the city on April 8 and headed for Montgomery, the first capital of the Confederacy, reaching the city on the 12th. The destruction of its war-making capacity, including the Alabama Arms Manufacturing Company and the Leonard and Riddle saltpeter plant, was quickly accomplished. Before retreating to Columbus, Georgia, the erstwhile defenders burned the city’s cotton resources—some 85,000 bales valued at an estimated $40 million.

Unaware of Lee’s surrender in Virginia three days before, Wilson was determined, in his words, “to continue breaking things along the main line of Confederate communication.” His next target was Columbus, gateway to the Peach State, 80 miles west of Montgomery. It was the last major manufacturing center and storehouse untouched by Union raiders. Although there was little Confederate strength to seriously contest the Yankee advance to Columbus, on the way skirmishes were many and often brisk. Like Selma, Columbus, situated on the east side of the Chattahoochee River, was well fortified. It was protected from attack from the west by steep hills ranging in height from 100 to 500 feet. Traffic across the river was carried by two foot/wagon bridges as well as a railroad trestle at the southern end of the city about 500 yards from the lower bridge.

In charge of the defenders was the former secretary of the treasury under President James Buchanan, the first president of the Confederate Congress, Maj. Gen. Howell Cobb. The northern approach to the city was covered by a line of rifle pits, and two forts. The main defensive position, at the bridgehead, was a fishhook-shaped line of rifle pits supported by 11 artillery pieces extending midway between the two wagon bridges north for a mile before hooking to the east. There were four guns at the lower bridge, two at the east end of the upper bridge, and four at the east end of the railway trestle. The Confederate defenders numbered 3,000 men and 27 guns.

Upton’s division reached Columbus on April 16. His plan of attack called for a force of dismounted troopers to hit the upper bridge hard enough to break the enemy defenses there. After that was done, a mounted contingent would secure the bridge and enter the town. Wilson soon arrived and approved Upton’s plan, ordering it to be carried out as a night attack. At 9 pm, Winslow’s 3rd and 4th Iowa and the 10 Missouri Cavalry Regiments moved out. The latter unit passed through the Confederate first line and gained the bridge, but without adequate support withdrew to the Federal starting line.

In a second attempt to break the enemy’s position, the 3rd and part of the 4th Iowa, both dismounted, again attacked the Confederate line, this time routing the enemy. The Federals then went for the bridge. The 4th Iowa captured a Confederate battery at the west end of the structure, then struggled across the span, capturing another gun position at its east end. As the last defenders were driven off from the bridge area, a mounted battalion of the 4th Iowa clambered across the river and into Columbus. While Upton took Columbus, LaGrange’s brigade, after a sharp fight on the 16th, took Fort Tyler, thus securing West Point. The victory netted LaGrange 19 train engines and 340 railway cars.

“Our Task Was Done and Done Well”

Columbus and Fort Tyler proved to be the final major battles of Wilson’s campaign, but his march did not end at those locations. Macon, Georgia, was his next objective. Long’s division, now under the command of Colonel Robert H.G. Minty, led the way while Long was still recovering from his Selma wound. Skirmishing with small parties of Confederates and destroying anything of military value he could find, Minty was 13 miles outside of Macon when he got word from the garrison of a truce signed by Sherman and Confederate commander Joseph E. Johnston. Not certain of the authenticity of the report, Wilson pushed on to Macon, occupying the town on April 20 and accepting the surrender of its 3,800-man garrison and 60 pieces of artillery.

By the 21st, having heard conclusively from Sherman that a truce had been arranged, Wilson stopped his eastward advance. The last major military operation of the Civil War ended. Wilson’s superb campaign left a legacy demonstrating that a force able to make rapid movements and lay down high volumes of firepower could conduct independent operations with great prospects for success. In less than two months of campaigning, he and his veteran troopers had destroyed seven irons works, seven foundries and machine shops, 13 factories, three arsenals, a naval yard, five steamboats, 35 locomotives, nearly 600 railroad cars, and countless miles of railroad tracks. “Our task was done and done well,” Wilson reported. He was not exaggerating.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments