By Don Hollway

The citizens of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, awoke one morning in late June 1863 to find the Civil War literally at their doorsteps. Because the bulk of the fighting to that point had taken place in the South, residents of most Northern states were far removed from the war, except for what they read in their newspapers. For the residents of Gettsyburg, that situation was about to change.

The neatly laid out town, with many of its homes and businesses made of sensible Dutch brick, was not nearly as obscure as legend would have it. With a wartime population of 2,400, it was actually in the upper 25 percent of all Northern cities in size. More than that, as seat of Adams County, Gettysburg was an important crossroads location for commercial traffic, boasting a railroad station, a new courthouse, several hotels and taverns, a theological seminary, a college, and a county jail. Its business center featured a thriving carriage-building industry, several tanneries, and 22 shoemakers. Contrary to what many Confederates had been led to believe, there were no local warehouses bulging with shoes. They had all gone toward the Union war effort.

Patriotism Flourished, But the War Seemed Far Away

Patriotism flourished in Gettysburg, with the town raising three separate volunteer infantry units—the Independent Blues, the Adams Rifles, and the Gettysburg Zouaves—and a Ladies Union Relief Society that sewed flannel shirts and other homespun garments for the boys at the front. The ladies also answered an appeal from the United States Sanitary Commission to send boxes of blankets, food, and clothing to military hospitals in Baltimore.

Still, the war seemed comparatively far away until Gettysburg residents received their first warnings in late June 1863 of a new Confederate invasion threat, mounted nine months after a previous Rebel advance into Maryland. Men mustered into the hastily formed 26th Pennsylvania Emergency Volunteer Infantry and patrolled roadways west of town, felling large trees across the thoroughfares to impede approaching Confederates. Everyone was on edge.

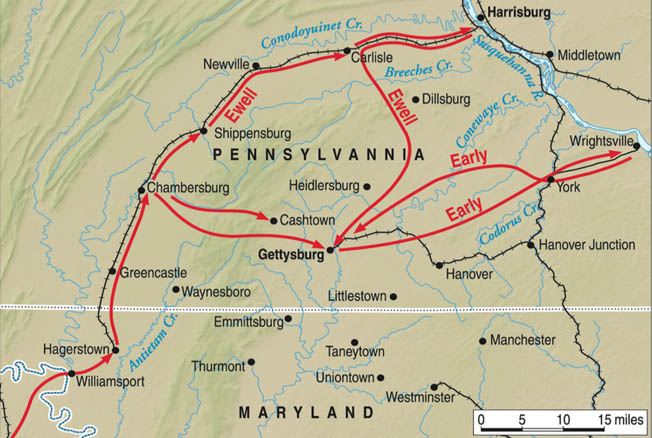

At 8 am on June 26, the first Confederates neared Gettysburg, the sharp spearpoint of Lt. Gen. Richard S. Ewell’s II Corps of the Army of Northern Virginia. A week earlier Ewell had received orders from General Robert E. Lee to march his corps into Pennsylvania ahead of Lee and the rest of the army. Ewell, accordingly, had crossed into Pennsylvania. While he led two divisions toward the state capital at Harrisburg, Ewell ordered Maj. Gen. Jubal Early to take his 6,500-man division across South Mountain to Gettysburg and then proceed to York, cut the North Central Railroad, and destroy the bridge across the Susquehanna between Wrightsville and Columbia.

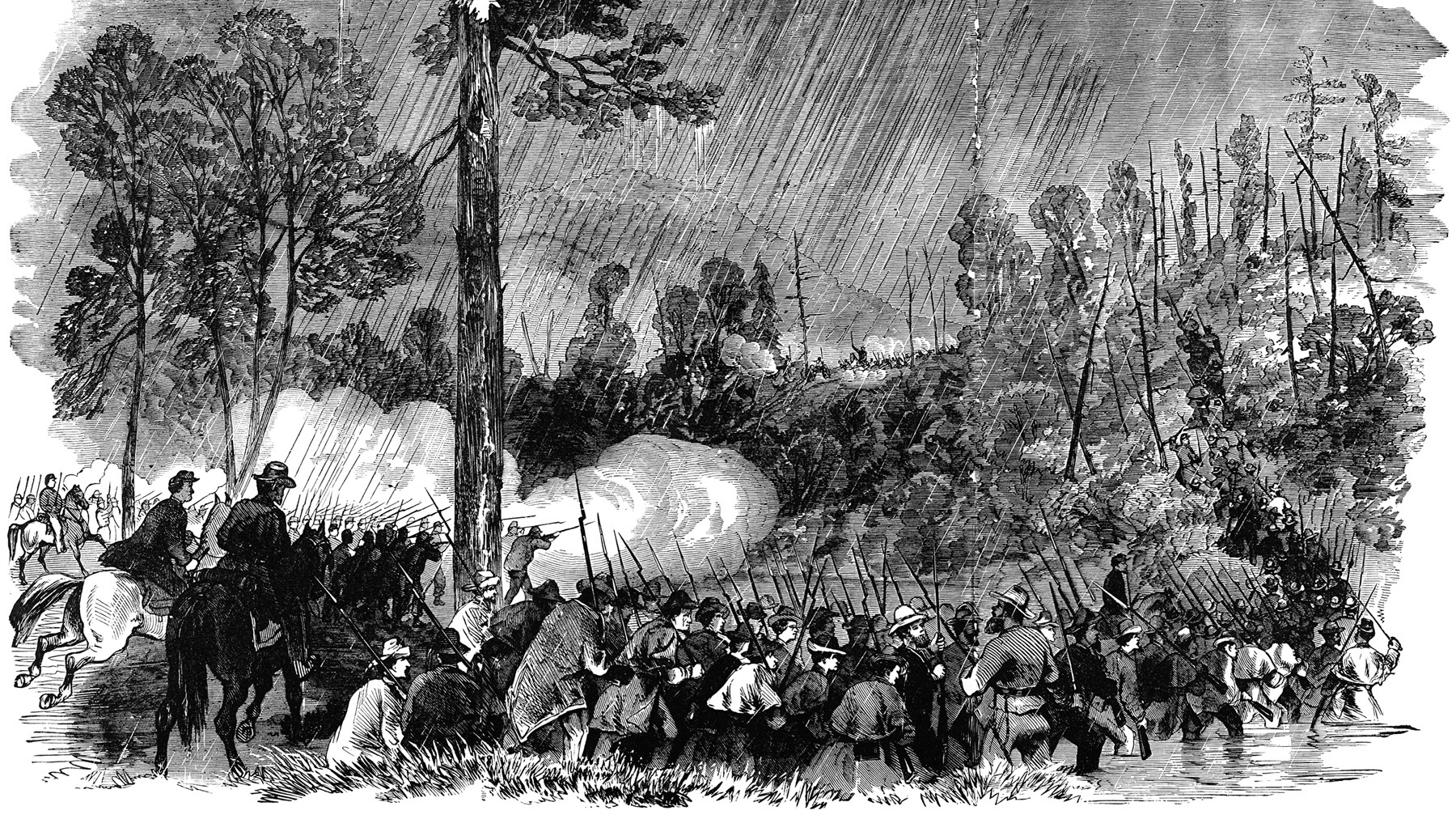

On the morning of the 26th a cold drizzle fell as Early’s men marched toward Gettysburg, pausing along the way (in direct contravention of Lee’s standing orders not to destroy private property) to burn the Caledonia Furnace Iron Works owned by Republican Congressman Thaddeus Stevens, one of the harshest Northern abolitionists. Receiving information that local militia had massed at Gettysburg, Early decided to approach the town from two different directions. He sent Maj. Gen. John B. Gordon’s infantry division and Lt. Col. Elijah V. White’s 35th Battalion, Virginia Cavalry, directly down the Cashtown Pike, while Early and the balance of the division approached Gettsyburg from the north on the Hilltown Road.

No Match for the Fire-Tested Confederates

The green militiamen were no match for White’s fire-tested Confederates, who easily brushed them aside, killing 20-year-old Private George Washington Sandhoe and charging into Gettysburg in a style befitting their unit nickname, the Comanches. “It seemed as if pandemonium had broken loose,” recalled Gettysburg resident Lydia Catherine Zeigler. Professor Michael Jacobs of Pennsylvania College observed the cavalry’s arrival with true professorial disdain: “The advance guard of the enemy, consisting of 180 to 300 cavalry, rode into Gettysburg at 3:15 pm, shouting and yelling like so many savages from the wilds of the Rocky Mountains, firing their pistols, not caring whether they killed or maimed man, woman or child.” Disregarding the danger, 10-year-old Gates D. Fahnestock and his friends dashed to second-story windows to watch the proceedings “as they would a wild west show.”

Things settled down once Gordon’s infantry marched into town. “These Confederates were very firm and businesslike in their attitude toward the townspeople,” reported Henry Jacobs. But fellow resident Fannie Buehler, whose postmaster husband was in hiding for fear he would taken prisoner by the Confederates, had a less admiring view of the invaders. “I never saw more unsightly set of men,” she noted, “dirty, hatless, shoeless, and footsore.” A Southern flag went up in the town square, and regimental musicians annoyed citizens by playing “Dixie” and other patriotic Confederate airs long into the night. Years later, Gordon would look back on the opening salvo in the Battle of Gettysburg as a mere dustup: “I had met a small force of Union soldiers,” he said, “and had there fought a diminutive battle when the armies of both [George G.] Meade and Lee were many miles away.”

“You Boys Ought to be Home With Your Mothers”

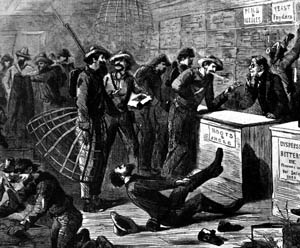

Early arrived in Gettysburg late that afternoon and went to the Adams County courthouse. There he reviewed the 175 bedraggled militiamen whom his troops had captured. “You boys ought to be home with your mothers and not out in the fields where it is dangerous and you might get hurt,” the general tongue lashed them. He then presented a list of demands to city fathers. Early wanted 7,000 pounds of bacon, 1,200 pounds of sugar, 1,000 pounds of salt, 600 pounds of coffee, 60 barrels of flour, 10 barrels of onions, 10 barrels of whiskey, 1,000 pairs of shoes, and 500 hats. Or, he said, he would accept $5,000 in cash. Borough President David Kendlehart rejected Early’s demands as exorbitant but promised that town merchants would “furnish whatever they can of such provisions.” In the end, Early had to settle for the 2,000 rations his men discovered at the train depot.

The next morning the Confederates rode out of Gettysburg, heading east toward York. At that point, Maj. Gen. Darius N. Couch had fewer than 250 men to defend the Union’s newly created 34,000-square-mile Department of the Susquehanna. He called for volunteers, but his main ally was the Susquehanna River itself. He was determined that no Rebel unit should cross it. There were only a few points where such a crossing was even possible. Between Harrisburg and the neighboring state of Maryland there was only one, east of York, between the villages of Wrightsville and Columbia.

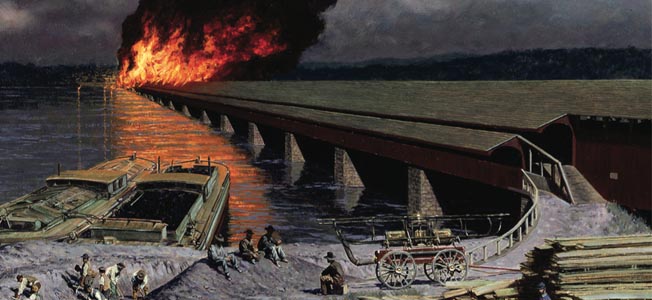

The World’s Longest Covered Bridge

There the river, a mile wide, made a formidable military barrier. In 1777, when the British occupied Philadelphia, the Continental Congress had retreated west across it to the safety of York, where its members signed the Articles of Confederation. Since then, an impressive bridge had been built over the river. Completed in 1834, the 5,620-foot-long Wrightsville-Columbia Bridge was the world’s longest covered bridge. It featured 27 wooden spans, each 200 feet long, 40 feet wide, and stout enough to bear loaded train cars. It rose on stone pylons 15 feet above the high water mark. As an intersection of road, rail, river, and canal traffic, Wrightsville was of much greater strategic import to the invading Confederates than Gettysburg.

Couch assigned its defense to Colonel Jacob Frick. With fewer than 1,000 men—most of them freshly recruited militia—Frick needed allies to stall the enemy advance until reinforcements arrived. Couch sent his aide-de-camp, Major Granville O. Haller. But the Confederates had easily scattered Haller’s militia and irregulars at Gettysburg, and they had no reason to stop there. Early’s orders to destroy the Wrightsville Bridge did not preclude capturing it first and linking up with Ewell from the far side of the Susquehanna. “I directed General Gordon, in the event of there being no force in York,” Early reported, “to march through and proceed to Columbia Bridge, and secure it at both ends, if possible.”

The rain cleared off Saturday morning. Gordon’s Georgia brigade led the way toward York, 30 miles away. His cavalry fanned out on his flanks, burning rail bridges, cutting telegraph lines and, as one lieutenant put it, “gobbling up all the horses, wagons, cattle and sheep for miles on either side of the march.” Fearing a sack, and despite Haller’s pleas, York surrendered. Early caught up to Gordon that evening a dozen miles from town. The Georgian reported, “I have been visited by a delegation from York, and have agreed to take possession of the town without destroying property.” Early replied, “I could not have given you better instructions.”

Early Makes Requisitions

York was the largest Northern city occupied by the Confederacy. As he had done at Gettysburg, Early moved quickly to extract all possible gain from the city. “I then made a requisition upon the authorities for 2,000 pairs of shoes, 1,000 hats, 1,000 pairs of socks, $100,000 in money and three days’ rations of all kinds,” he reported later. “Subsequently, between 1,200 and 1,500 pairs of shoes, the hats, socks, and rations, were furnished, but only $28,600 in money was furnished, which was paid to my quartermaster Major [C.E.] Snodgrass, the mayor and other authorities protesting their inability to get any more money, as it had all been run of previously, and I was satisfied they made an honest effort to raise the amount called for.”

Meanwhile, Haller reported to Couch that he was abandoning the city. Couch telegraphed Frick at Wrightsville: “York has surrendered. Our troops will fall back from there to-night. Tell the people of Lancaster that the time has come for action.” It was the Union’s darkest moment. That same Saturday, Army of the Potomac commander Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker tendered his resignation. Shortly past midnight, three brigades under Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart crossed the Potomac, a mere few dozen miles from Washington. At about the same hour, Maj. Gen. George Meade, shaken from his bed, was handed Hooker’s command. And rumor had it that, come daylight, some 35,000 Rebels would hit Wrightsville, take the bridge, and cross the Susquehanna into the heart of the Union.

Frick Marshals Threadbare Forces at Wrightsville

Church bells rang, but many services were cancelled as Gordon’s brigade rode unopposed into York at about 10 am. Reining up before frightened womenfolk in their Sunday best, Gordon “assured these ladies that the troops behind me, though ill-clad and travel-stained, were good men and brave; that beneath their rough exteriors were hearts as loyal to women as ever beat in the breasts of honorable men.” Not all of York’s citizens, however, feared rebel conquest. Soon after addressing the matrons, the general bent from the saddle to accept a bouquet of flowers from a girl “probably twelve years of age.” As he rode on, he discovered that it hid a note, “in delicate handwriting, purporting to give the numbers and describe the position of the Union forces of Wrightsville. It bore no signature, and contained no assurance of sympathy for the Southern cause, but it was so terse and explicit in its terms as to compel my confidence.”

While Early and Gordon were riding unhindered into York, a hard-pressed Frick was busy marshaling his threadbare forces at Wrightsville. A correspondent for the Pottsville Miners Journal reported the hasty defense efforts: “On Sunday we commenced digging rifle pits and had hardly completed them when our mounted scouts came in rapidly and reported to Colonel Frick that the rebels were approaching in force.” Frick redoubled his efforts.

At the west end of the bridge, Wrightsville lay in a mile-wide, rolling valley between two parallel, roughly east-west ridges. Frick’s entrenchments and rifle pits circled around the valley floor west of town. Together, he and Haller still had no more than 1,400 men total—by military tactics of the day enough to defend a 400-yard front. Their C-shaped perimeter was some eight times that far around. They had two bronze 12-pounder Napoleon cannons and a sharpshooting 3-inch Ordnance Rifle with a range of over a mile but arrayed them across the river to destroy the bridge if it was captured. They derailed hopper cars full of iron ore to block the entrance and barricaded Wrightsville’s streets with logs and planks from riverside lumber yards. Union cavalry patrolled the roads toward York, alert for the first sign of the approaching enemy.

Three Infantry Brigades & A Cavalry Regiment At the Ready

By 4:30 pm scouts reported no fewer than three brigades of infantry and a regiment of cavalry on the pike. The Pennsylvania militiamen, many of whom had never fired in anger, put down their shovels and took up their guns. The Miners Journal correspondent observed, “The men were placed by companies in the pits, and about 5 o’clock the firing became brisk in the front. We could see from our position, the rebel cavalry who mounted and dismounted, were engaged in driving in our pickets. Between that hour and half past 6 o’clock the firing was quite sharp and the rebels evidently were trying to flank our little force, and cut off our retreat to the bridge, distant about a half mile.”

Within the hour gray-clad troops were advancing through the fields of wheat and rye before the Union line. Gordon rode up the south ridge to look down upon the field of impending battle, comparing it to the note from his unknown accomplice in York. “There, in full view before us, was the town, just as described, a blue line of soldiers guarding the approach, drawn up, as indicated, along an intervening ridge and across the pike. Most important of all, there was a deep gorge or ravine running off to the right and extending around the left flank of the Federal line and to the river below the bridge.”

The Battle for the Bridge Was On

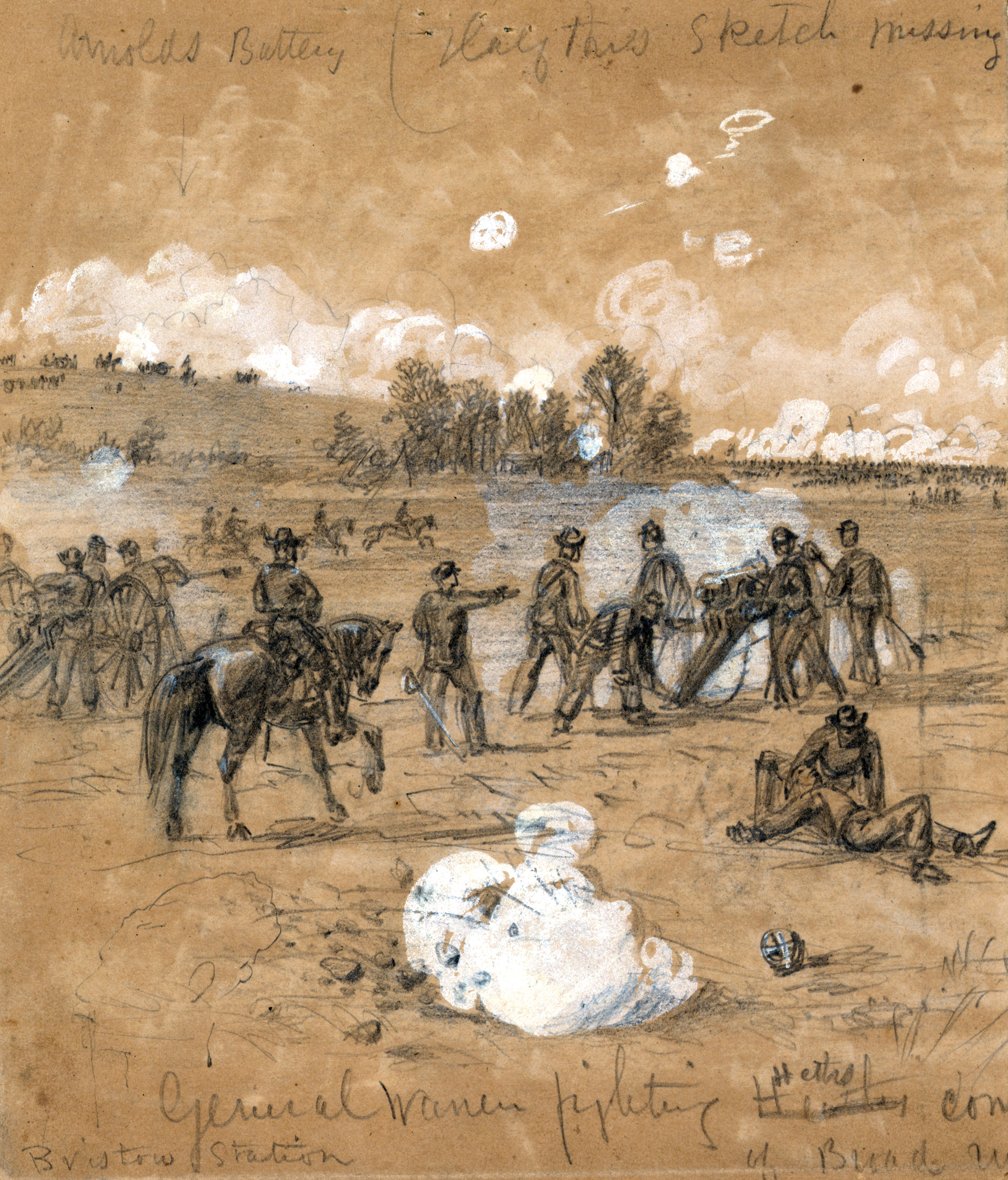

Contrary to Union fears, Gordon had no more than 1,800 men (he estimated them at just 1,200), but he also had four cannons. He ordered one pair of guns deployed opposite the enemy center and the other on the heights to the north. While they held the Federals’ attention he would launch his real assault elsewhere. “My immediate object was to move rapidly down that ravine to the river,” said Gordon, “then along its right bank [relative] to the bridge, seize it, and cross to the Columbia side.” Courtney’s Virginia battery, led by Captain William Tanner, lobbed 40 rounds of shell onto the Union line while the cavalry was moving into position to assault the enemy flank.

Around 6 pm, 50 dismounted Confederate cavalrymen of the 31st Georgia, probing up from the bottom of the ravine, ran into a squad of Yankee skirmishers and nearly shot Union Major Charles McLean Knox, one of Couch’s staff officers. He led a fighting withdrawal toward the Federal entrenchments. The battle for the bridge was on. “We moved by the direct pike to Wrightsville, on the Susquehanna,” Gordon reported. “At this point I found a body of Pennsylvania militia nearly equal in number to my brigade, reported by the commanding officer (whom we captured) at 1,200 men, strongly entrenched, but without artillery. A line of skirmishers was sent to make a demonstration in front of these works, while I moved to the right by a circuitous route with three regiments, on order to turn these works, and, if possible, gain the enemy’s rear, cut off his retreat, and seize the bridge.”

Confederates ducking through the high wheat in front of the Union center traded shots with militiamen popping up from their foxholes. Behind the Southern advance the first pair of cannons moved up, unopposed, to blast away from just 500 yards. The second pair, on the heights to the north, began hitting the Union line with oblique fire. With their heads down in their trenches, the Northerners took only one casualty—an unknown black volunteer fatally struck in the head by a shell fragment—but neither did they hold up the Confederate assault.

“It was difficult to do [the attackers] much harm or dislodge them,” Frick recalled of watching from his command post north of the pike. “They depended exclusively on their artillery to drive us from our position here.” The Miners Journal reporter observed Frick during the opening fight. “Colonel Frick passed quietly and exposed to the fire of the Confederate sharpshooters from the left to the right of our lines and whispered an order to the captains, an order to fall back to the bridge. This movement was affected in excellent order by the command, although exposed during the movement to a heavy fire of shell and to a galling one of sharpshooters. The shells exploded over us and in close proximity to our ranks and there were many narrow escapes. I am glad to say that the 27th Regiment had no men killed and but three or four slightly wounded. Had we moved from our pits five minutes later, my belief is that our retreat would have been cut off.”

Pitched To & Routed

Meanwhile, Haller sent Robert Crane, superintendent of the Reading & Columbia Railroad, with a demolition crew of 19 carpenters onto the bridge. At the fourth span from the west bank—800 feet out on the water, far enough to prevent easy repairs—they sawed partway through the arches and key load-bearing spans. They filled boreholes with black powder, ripped up planking, and rolled barrels of kerosene and coal oil to the spot. Then they knocked holes into the roof and walls to let the fire breathe. Haller posted guards to ensure that if his troops panicked and rushed the bridge, no one would set off the charges prematurely.

Outside Wrightsville the fight neared the breaking point. “We pitched into them,” wrote one Confederate lieutenant, “and after a brisk little battle of about a half-hour duration, routed them.” Frick had gone around the line in full view, risking Confederate cannon fire and sharpshooters, giving the word to retreat. As one militiaman admitted, they all dropped everything and “fled in utter confusion from Wrightsville to the bridge.” A Union defender agreed with that assessment. “In a moment all was confusion, and the retreat began in good earnest,” he wrote of the flight into town. “The route all along that back street was covered with blankets, knapsacks, &c., dropped by the men.”

“We drove them pell-mell through the streets of Wrightsville,” declared a sergeant of the 38th Georgia. But after marching 20 miles and fighting a battle at the end of it, the Confederates were too played out to keep up the chase. “When a Yankee does run, he can outrun anybody, and there is no use in trying to catch him by a stern chase,” decided one Georgian. “You either have to head him off or give it up as a hopeless case.”

Forming a Final Assault on the Riverbank

The Confederate cannoneers lifted their muzzles and began dropping shells into the town itself. Several militiamen were wounded by fragments; a Union captain was hit in the leg and, although hidden from capture and cared for in a local home, he later died. Rebels poured into town from the north, south, and west, sweeping up 20 Federals before they could reach the bridge. One Union lieutenant later wrote that if they had waited five more minutes to retreat, none would have made it.

Haller was way ahead of them. Confirming that Crane was ready to blow the bridge, he rode on across it and proceeded into Columbia to take charge of the Union artillery, completing the retreat he had conducted all the way from Gettysburg. Knox and Frick remained at the western entrance, shepherding the last of their men through the maze of overturned rail cars before following them inside. The Georgians paused a moment on the Wrightsville riverbank, forming for the final assault.

“Once across,” Gordon wrote later, “I intended to mount my men, if practicable, so as to pass rapidly through Lancaster in the direction of Philadelphia, and thus compel General Meade to send a portion of his army to the defense of that city.” A few Confederate cavalrymen led the way, clattering through the overturned rail cars and briefly onto the bridge, firing down the tunnel to test for a response and finding none. Company G of the 38th Georgia marched up and onto the bridge, heading straight for Philadelphia.

Eight hundred feet away, only Knox, Frick, Crane, and four demolition men remained to stop them. In a remarkable display of courage, coolness, and sheer military protocol, Frick ordered Knox to blow the bridge. Knox passed the word to Crane who in turn signaled his men to light their fuses. Then everyone ran for the east end, almost a full mile away. It was about 7:35 pm.

A Curl of Smoke Rises From the Pier…

A Harper’s Weekly reporter among the crowd watching from the east bank wrote, “Three reports were heard in quick succession, followed by a cloud of smoke.” Confederates on the high ground behind Wrightsville saw the exploding timbers of the bridge rise high into the blue sky. “Every charge was perfect and effective,” Crane declared. But the bridge’s oaken beams were stronger than expected. When the powder smoke cleared, one observer said, it could be seen that the explosion had “simply splintered the arch. It scarcely shook the bridge.”

The Wrightsville-Columbia Bridge was still standing.

As Crane later said, “The rebel cavalry and artillery approaching the bridge at the Wrightsville end, Colonel Frick, in order to more effectually destroy the connection (the bridge not falling), ordered it to be fired.” The men stove in the barrels of kerosene and coal oil over the bridge floor and put it to the torch. Around 8 pm observers saw “a curl of smoke rising from the pier, and shortly after a column of flame mounted high in the sky.”

The initial explosion had flushed the Georgians out of the bridge. Now they rushed back in. “With great energy,” Gordon wrote, “My men labored to save the bridge. I called on the citizens of Wrights-ville for buckets and pails, but none were to be found.”

An evening squall, rather than dampening the flames with rain, fanned them higher with wind. The bridge burned from the center toward both ends. Against the low-hanging clouds, the glow of a mile of blazing oak was visible in Hanover, 30 miles west, and Harrisburg, 30 miles north. “My people driven over Columbia Bridge,” Couch telegraphed Meade. “It is burned. I hold the opposite side of the river in strength at present.”

By firelight a Confederate detachment felt its way partly across a dam built a few hundred yards downstream, but previous days’ rains had raised the river, and with Union guns trained on them they soon gave it up. Still, they earned the distinction of pressing farther east than any other Confederate troops during the Gettysburg campaign.

Southern Plans Go Up in Smoke

Gordon could only sit on his horse in the drizzle, watching the bridge and Southern plans go up in smoke. Early chose this moment to ride into Wrightsville, having seen “an immense smoke rising in the direction of the Susquehanna. I regretted very much the failure to secure this bridge,” he would write, “as the river was otherwise impassable, being very wide and deep at this point. I therefore ordered General Gordon to move his command back to York next day, and returned to that place myself that night.”

Meanwhile, embers from the inferno began falling in Wrightsville. The Confederates suddenly found themselves with a new battle to fight and new allies. “When the burning bridge fired the lumber-yards on the river’s banks, and the burning lumber fired the town,” Gordon recalled in grim humor, “buckets and tubs and pails innumerable came from their hiding-places, until it seemed that, had the whole of Lee’s army been present, I could have armed them with these implements to fight the rapidly spreading flames.”

Together Northerners and Southerners formed a bucket brigade. The fire claimed three riverside houses, a foundry, mill, and lumber yard, but Wrightsville was saved. Nor, as far as the Confederates were concerned, was all lost. Ewell’s other two divisions were now across the river from Harrisburg; Gordon and Early could march upriver to join the assault. It was not to be. At about that same hour, Robert E. Lee learned that the Army of the Potomac was pressing north. On Monday he issued new orders: “We will not move to Harrisburg as expected, but will go over to Gettysburg and see what General Meade is after.”

A Critical Skirmish

On the scale of the Civil War, the battle for the Wrightsville-Columbia Bridge amounted to little more than a skirmish. Looking back 150 years later, however, those last days of June 1863 suggest an alternate timeline, one in which the Civil War turned out much differently. But for the 15-minute confrontation at the bridge, Gordon and Early might well have crossed the Susquehanna into the very heart of the North. Who knows what havoc might have ensued.

Instead, Union cavalry made a stand on the same high ground northwest of Gettysburg, near Oak Hill and Willoughby’s Run, where Confederates had camped less than a week earlier. Other Federal troopers held up a Rebel advance down the same Chambersburg Pike that Gordon had ridden in his conquest of Gettysburg. By the next day, Meade and Hancock held the high ground on Cemetery Ridge, which Southern cavalry had already swept clear of Haller’s militia. And on the afternoon of Friday, July 3, at the “High Water Mark of the Confederacy,” the last of Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s division fell back in defeat from the Bloody Angle, ground that the Confederates had already taken once, but now had lost forever—thanks in part, at least, to the brief but impactful occurrence at Wrightsville Bridge a week before.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments