By William E. Welsh

Thousands of Protestant Swedish and German soldiers struggled up the rain-slickened slopes of a high ridge in southern Germany on September 3, 1632. The Protestant pikemen and musketeers struggled to breach obstacles and trenches fiercely defended by Catholic soldiers on the high ground surrounding an old fortress known as Alte Veste overlooking the Rednitz River in Franconia.

Although shells from their heavy guns blasted the fortifications, the troops of Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus could not make any headway against the formidable fieldworks constructed by Count Albrecht von Wallenstein’s Imperial army. As the Protestants withdrew, leaving several thousand dead soldiers on the muddy hillside, the Imperial troops surged forward capturing large numbers of them. One of the captured men was Lennart Torstensson, the Swedish artillery commander who was one of Gustavus’ most trusted generals.

The Catholics imprisoned 29-year-old Torstensson in the Bavarian city of Ingolstadt on the Danube River. The Swedish army obtained his release through a prisoner exchange in August 1633, and he returned to Sweden to convalesce. His health had sharply declined during his incarceration under poor conditions, and complications would not only afflict him during the remainder of his military service, but ultimately cut short his life.

The son of an aristocratic Swedish family, Torstensson became a page to King Gustavus II Adolphus at the age of 15 in 1618. The Swedish king had undertaken the reform of Sweden’s military forces building upon the tactical concepts of Maurice of Nassau, the Prince of Orange, who sought to elevate the Dutch army to the point that it could successfully take on the crack troops of the Spanish army, whose soldiers were the best in Europe in the 16th and early 17th centuries.

Torstensson’s first experience in battle came in the service of the Swedish king while he was campaigning in Livonia. Having seen that Torstensson had the aptitude to become a skilled commander, the king sent him in 1624 to The Netherlands to study under Maurice. During that time, Maurice imparted to him his knowledge of artillery and how it might be used effectively on the battlefield.

After gaining substantial success in Livonia against the Poles at the Battle of Wallhoff in January 1626, Gustavus invaded Polish Prussia by sea four months later. Torstensson joined the Swedish king for the campaign in Prussia. The war dragged on for three years, at which time the combatants concluded a treaty that gave the Swedes Livonia. Gustavus completed many of his key military reforms during the Polish Wars.

Gustavus made Torstensson his artillery chief. With the king’s assistance, Torstensson consolidated the army’s heavier guns into batteries, redesigned the 12-pounder gun giving it a lighter carriage, and distributed four 3-pounder guns to each regiment. Torstensson not only commanded the gunners of the Swedish field army, but also its miners and pioneers. Although he had overall command of the artillery units, he only had direct control of the heavier guns, for the king had directed that regimental infantry commanders were to be allowed to use the 3-pounder guns as they saw fit.

Gustavus Adolphus’ expeditionary army landed in western Pomerania at Usedom on July 6, 1630, to support the German Protestants against the armies of the Catholic Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II. Gustavus’ powerful army consisted of 43,000 Swedes and Finns, as well as 30,000 foreign mercenaries.

Although Danish King Christian IV had fared poorly against the combined Imperial and Bavarian forces, Gustavus would use revolutionary tactics against the Catholic armies of Austria and Bavaria that fought in tercio formations like the Spanish. Rather than fighting in dense tercios with files up to 50 men deep, Gustavus’ infantry would fight in linear fashion with batteries of 24-pounder and 12-pounder guns furnishing direct support.

European powers began using gunpowder cannons in the 14th century, but it was Gustavus’ Swedish army that established the first regular artillery units. As the Swedes began fighting pitched battles with the Imperial Catholic armies, it became evident that they had the best artillery in Christendom. Only the artillery of the Ottoman Turkish armies could rival that employed by the Swedes during Gustavus’ campaign in embattled Germany.

The first major test of the Swedish artillery came at Breitenfeld in Saxony on September 7, 1631, when Gustavus offered battle to Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly, who commanded the combined Imperial and Catholic League forces. During the hard-fought contest, Torstensson skillfully directed the Swedish batteries, and these units exhibited superior firepower in comparison to their Catholic counterparts. The well-trained Swedish gunners proved at Breitenfeld that they could fire as many as four shots a minute in the heat of battle.

After wintering in the Rhine Valley, Gustavus’ Protestant army swept into Catholic Bavaria in April 1632. Tilly’s army had a strong position behind the Lech River, a right tributary of the Danube River, but Torstensson brilliantly used his heavy guns to create a diversion by bombarding the Imperial center on the opposite bank, while Finnish pioneers constructed a pontoon bridge six miles to the south to gain a foothold for the Swedish troops on the east bank of the river. Once the bridge was in place, the Finns dug artillery pits for guns that rumbled across the bridge to furnish direct support for the troops advancing against the Imperial left wing. The ensuing battle was a decisive Protestant victory. The loss of Tilly, who was mortally wounded by musket fire, was a major loss to the Catholics.

After securing southern Bavaria, Gustavus occupied the strategic city of Nuremberg on the northern frontier of Bavaria. Count Albrecht von Wallenstein, a reliable commander of Imperial forces, established a fortified camp nearby on the grounds of the old hilltop fortress at Alte Veste. During Gustavus’ unsuccessful assault on the camp, Torstensson was captured and interred in Ingolstadt south of Nuremberg. While Torstensson was imprisoned, Gustavus was slain in battle at Lutzen that November.

After Lutzen, the Swedish army suffered a major defeat in September 1634 at Nordlingen in Bavaria against an Imperial army heavily reinforced by Hapsburg Cardinal-Infante Ferdinand’s Spanish army, which was on its way overland from Italy to the Spanish Netherlands. Count Gustav Horn, who led the Swedish component of the Protestant army at Nordlingen, was captured. At the time of the battle, Marshal Johann Baner, who had succeeded Gustavus as supreme commander of the Swedish forces, was campaigning in Silesia with a secondary Swedish army. After a brief convalescence, Torstensson became Baner’s chief of staff, with the rank of major general.

The Swedes felt a keen desire to avenge their humiliating defeat at Nordlingen. In a stroke of good fortune for the Protestants, Emperor Ferdinand II ordered his troops to assassinate Wallenstein in 1634 for alleged treason. A leadership vacuum occurred after his death, for the Catholics possessed no general who was comparable to either Tilly or Wallenstein. When the Imperialists under Melchior von Hatzfeldt invaded Brandenburg, Baner attacked them at Wittstock in October 1636. He defeated them by dividing his forces and sending one group on a wide flanking maneuver that caught the Imperialists by surprise. Torstensson directed the powerful Swedish artillery, which pinned the Imperialist army in place and prevented Hatzfeldt’s troops from launching any successful assaults.

Over the course of the next five years, the advantage shifted back and forth, but the Swedes found themselves still not able to inflict a final defeat on the Catholic armies of Bavaria and Austria. Emperor Ferdinand II died in 1637 and was succeeded by his eldest son Ferdinand III. Baner’s health declined substantially, and he died in Halbertstadt in May 1641.

Swedish Lord High Chancellor Axel Oxenstierna, who directed the military forces of Sweden on behalf of Queen Christina, picked Torstensson to succeed Baner. Torstensson faced a herculean task: He would have to fight his way into to the frontier of Austria. To keep his army in supply, he would have to capture and garrison a string of fortified cities between the Swedish-controlled Baltic ports in Pomerania and the emperor’s seat of power in Austria.

Torstensson began his 1642 campaign by capturing major fortresses in Silesia to serve as way stations for troops and supplies on their way south to future operations in Saxony, Moravia, and Bohemia. Next, he besieged Leipzig, the capital of Saxony, with his 20,000-strong army to compel the Imperial army to attempt to relieve it. As expected, Archduke Leopold Wilhelm arrived in Saxony with 26,000 Imperial troops to fight the Swedish army.

The two opponents squared off in October at what became the Battle of Second Breitenfeld. The battle began with the Swedish right wing advancing towards the Imperialist left wing. At the same time, Ottavio Piccolomini’s crack cuirassiers and Croatian irregulars attempted to turn the Protestant army’s left flank, but the Swedish cavalry checked their advance. When Swedish troops streamed out of the woods to attack the Imperial left wing, it crumbled. Many of the Imperial troops surrendered. Torstensson’s victory at Second Breitenfeld gave the Swedes control of Saxony, and they garrisoned its capital for the rest of the war.

The following year, Oxenstierna summoned Torstensson to Sweden to prosecute a new war against Sweden’s long-time foe, the Danes. His opponent during the conflict was General Hannibal Sehested, Danish King Christian IV’s son-in-law. The conflict was known afterwards as Torstensson’s War. Torstensson overran the Danish defenses and wintered in Holstein in 1643-1644.

Christian IV appealed to Ferdinand III for military assistance, and the emperor dispatched untalented general Count Matthias Gallas with 15,000 troops to assist the Danes. The inept Gallas tried to bottle up the Swedes in Holstein the following year, but Torstensson slipped out of the trap. Fearing that the Imperial troops might try to capture Swedish ports in Pomerania, Torstensson marched east to Brandenburg to block such a move. He skillfully outmaneuvered Gallas, who soon found his army encircled by the Swedes at Juterbog south of Berlin. Although the Imperial foot soldiers succeeded in breaking out, the Swedes wiped out all 4,000 of the Imperial cavalry troops.

Torstensson pressed the offensive against Emperor Ferdinand III in 1645 by invading Bohemia, where the war had begun in 1618. The emperor had replaced Gallas with Field Marshal Melchior von Hatzfeldt. To compensate for the loss of the Imperial cavalry, a Bavarian cavalry force under General Johann von Werth had arrived to reinforce Hatzfeldt.

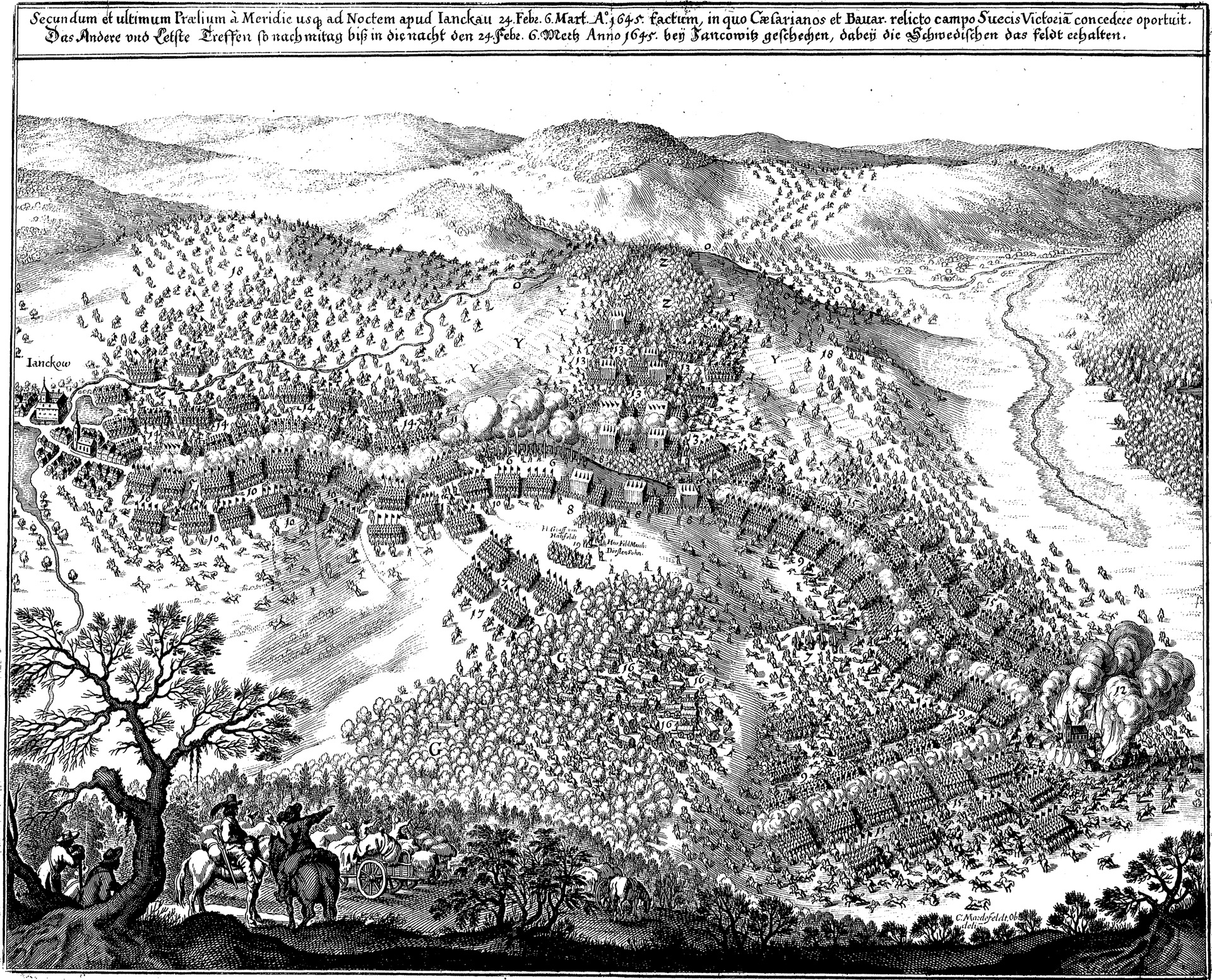

The two armies collided in wooded and broken terrain at Jankov south of Prague on March 6. Torstensson fielded 9,000 horse, 6,500 foot, and 60 cannon, while von Hatzfeldt arrived on the field of battle with 11,500 cavalry, 5,000 infantry, and 26 guns. The battle began badly for the Imperialists when General Johann von Goetz, one of the Imperial generals, advanced his troops from a ridge into a valley without requesting permission to do so. While Hatzfeldt tried to sort things out, Werth made a spirited attack with his horsemen, but the Swedish artillery broke up their charges.

Swedish troops skillfully conducted a turning manuever against the Imperial left that forced Hatzfeldt and Werth to withdraw their troops north to a second position. In a move not previously seen on Thirty Years War battlefields, the Swedish artillery kept pace with the advance. Imperial pike and shot troops tried desperately to construct breastworks, but the second Swedish assault came too quickly for them to entrench. The Swedes smashed the Imperial center and destroyed most of Hatzfeldt’s army. The Imperial army suffered 9,000 casualties, while the Swedes lost only 3,000 men.

Jankau became Torstensson’s tactical masterpiece. The victory was made possible in large part because of the crack Swedish artillery, which swept rapidly over streams and marshes still frozen in the late winter. Jankau earned Torstensson a place in the pantheon of great Swedish commanders of the Thirty Years War.

But it was to be his last hurrah. Torstensson’s chronic gout had grown nearly unbearable by the time of Jankau, and he retired the following year, just two years before the end of hostilities. While serving as the commander-in-chief of Swedish forces, he displayed great talents as a tactician. But he is best remembered for his artillery achievements. With the exception of Gustavus Adolphus, no other Swedish general came close to rivaling Torstensson for an understanding of the capabilities of gunpowder artillery on the battlefield.