By Diane Condon-Boutier

Every February 11, Rouxmesnil-Bouteilles, a tiny town in Upper Normandy situated north of the Seine River a short distance inland from the coastal city of Dieppe and some two hours from the D-Day invasion beaches, pays homage to 10 American airmen who crashed into the town center, narrowly missing the local children assembled in their schoolhouse just a few yards away.

It was 9:54 am, Friday, February 11, 1944.

A young civilian couple, Jeanine and Raymond Leconte, were in the kitchen of their home on the Rue des Jardiniers when the Consolidated B-24 bomber smashed through their ceiling, destroying the house and killing them instantly. No crewmember survived.

The V1 Menace From Across the Channel

As did the Kaiser in World War I, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler had reached the point in World War II when he decided to tread on any residual qualms about playing dirty and deployed acts of terrorism on the English civilian population. In both cases the objective was to kill women and children in hopes of demoralizing the British troops on the front lines and to wreak such havoc at home in England that civilians would rise up against their government and demand an immediate end to the conflict via unconditional surrender.

In World War I, the vehicle of this policy was the Zeppelin. Attacks by the enormous but lethargic airship, nicknamed “the baby killer” by the British, terrorized the populations of the eastern coast of England and eventually London. These attacks were to be copied almost exactly by the Nazis in the latter stages of World War II, this time using unmanned missiles nicknamed “doodlebugs” but more specifically, the V-1 and, later, the V-2 rocket.

The early versions of the “V” series of airborne missiles were designed starting as early as 1936 in the now infamous laboratories at Peenemunde. The novelty of these engines of destruction was the lack of risk, other than monetary, to the Third Reich. They were unmanned. No brilliant piloting was necessary, and thus no brilliant pilots could be lost.

If a V-1 were shot down by Allied pilots, it would represent an economic loss, but in the meantime it might keep the Allies frantically flying around, chasing unmanned missiles, occupying their pilots while the fast diminishing number of Luftwaffe pilots could be put to better use elsewhere.

Of course, Hitler’s ultimate goal was not to send up targets for the Allies, but to target their cities, preferably London, where damage could be spectacular, all at no cost of human life—no German human life, that is. In short, the plan was quite brilliant, if indeed sordid and amoral.

Taking all of these factors into consideration, the obvious Allied response to the arrival on the scene of the V-1 was to nip the plan in the bud. To that end, squadrons of bombers took off from bases in the United Kingdom regularly searching out launch sites under construction, scattered throughout the northern zones of France primarily in Upper Normandy and the Pas de Calais regions. In 1944 there were an estimated 400 V-1 launch sites located in these areas, some of which were completed and happily firing up to 100 missiles per day. The remainder were still under construction.

The difficulty in bombing these sites lay in their configuration. A V-1 launched close to the ground—almost horizontal to the ground—with a low-angled trajectory, making it possible to camouflage the launch site in a thick forest or even in farm buildings. In wooded areas the sites were assembled under thick tree cover, many in the huge national forests abounding in northern France. All that was needed was a space along the perimeter of the trees, breaking onto farm fields for example, and the construction site would be virtually invisible from the sky.

Such was the difficulty in detecting these sites that the Allies resorted to tried and true methods such as the carrier pigeon. At the museum at Utah Beach, visitors can see a tiny barrel attached to a parachute that contained a carrier pigeon sporting a small map of the area captioned with the very historic and easily recognizable motto for the Order of the Garter: “Honi Soit Qui Mal Y Pense.”

A local who came upon such a pigeon could simply mark the location of a V-1 launch site with an “X,” release the pigeon, and hope it wouldn’t fall victim to the slingshot of a local boy hunting his family’s supper. “Pigeon aux petit pois” was considered a rare delicacy, as keeping pigeons had been outlawed at the beginning of the war. If the pigeon made it back home to England, his heroic journey would help the Allies pinpoint the coordinates of one of the launch sites and hopefully bomb it to smithereens.

The Lonesome Polecat

It was on one such bombing raid, on February 11, 1944, targeting the launch site at Siracourt in the Pas de Calais region, that the 330th Bomb Squadron, 93rd Bombardment Group lost one of its planes. The Lonesome Polecat took off from RAF Station 104 in Hardwick, Norfolk, England, early that day, heading for the northern reaches of France. The squadron’s mission was to demolish the V-1 ramp still under construction.

It must be said that these raids were rarely accurate, largely for the reasons mentioned. There was a significant amount of collateral loss of life among the French civilian population and also among the Russian and Polish prisoners of war who were in essence slave labor, pouring the concrete and working on the sites under the guard of a handful of heavily armed Germans. A huge amount of damage was inflicted on local farms and livestock as well. The collateral damage didn’t disturb the Nazis in the least.

Damage caused to the building sites did create some degree of frustration for the officers overseeing the construction, but they simply moved to a nearby site and started over. By 1944, things were going badly for the Germans, and any progress toward a capitulation by Great Britain couldn’t carry a price tag deemed too high. If they could force the British to pull out of the alliance, the Americans would no longer have a European base. This would complicate things to such an extent that victory for the Third Reich would not only be possible, but once again probable.

Lonesome Polecat, the ill-fated B-24, number 42-63978E, was named for an Indian character in Al Capp’s Li’l Abner comic strip. The plane’s nose had been jauntily decorated with a painting of an American Indian. The name was apparently very popular as a later B-24 was christened Lonesome Polecat Jr. and a B-17 was dubbed Lonesome Polecat II.

It is quite possible that this particular Lonesome Polecat was manufactured by the Ford Motor Company in its massive Willow Run, Michigan, plant. It would appear that Henry Ford had revised his initial admiration of Adolf Hitler’s leadership qualities because, by 1944, Willow Run was churning out an astounding 14 airplanes per working day; a total of 2,728 B-24Ds would be manufactured there.

Willow Run also produced the lion’s share of the Waco CG4A gliders used by the Americans of the 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions in the D-Day landings in the Cotentin Peninsula around Sainte-Mère-Église. The B-24 became the flying workhorse of the American Army Air Forces, with an amazing 16,188 aircraft produced by various manufacturers—over 400 of which were awaiting modifications at the end of the war and ended in the scrap heap.

The 10 Men of the Lonesome Polecat

The crew of the Lonesome Polecat numbered 10, including a pilot, co-pilot, navigator, bombardier, radio operator, left and right waist gunners, top and belly turret gunners, tail gunner, and a mechanical engineer. Although 11 positions are listed, at times crewmen performed more than one function. This group of men hailing from the four corners of the United States spent ample time together, bonding into a cohesive unit in the cramped confines of their workplace. They learned to speak to each other under duress using the odd language of the initiated, the lingo of a team of flying heroes, incomprehensible to their grounded colleagues.

So who were these men?

They were 10 individuals hailing from areas of the United States as diverse as their civilian jobs.

Omar A. Turner

Prior to joining the U.S. Army Air Forces, the plane’s pilot, 28-year-old Captain Omar A. Turner, service number O-669815, was a general office clerk from Fulton, Georgia. His two years of college brought him into the Army as a private, yet 23 months later he was at the stick of the Lonesome Polecat and had been for some time. A bachelor born in 1916, he was just 28 years old when his plane was shot out of the sky over Rouxmesnil-Bouteilles in Normandy.

Hubert R. Tardif

The co-pilot of the Lonesome Polecat was 1st Lt. Hubert R. Tardif, service number O-731694, of Denver, Colorado. He enlisted in May 1942 as a private. He had two years of college and, at the age of 25, his profession as stated on his enlistment records was that of an actor. Few professions incite as much curiosity as this one. How an actor ended up co-piloting a B-24 stretches the limits of imagination, but his personal story went with him to his grave.

Theodore H. Olson

Bombardier 2nd Lt. Theodore H. Olson, service number 17062760, was born in Minnesota. In 1944 he was 24 years old and had spent just two years in the Army, having been drafted in February 1942. A resident of Ramsey, Minnesota, his job was something vague in the category of packing, filing, labeling, marking, bottling, and related occupations. Did he work in a brewery? Perhaps.

Olson’s position on board the Lonesome Polecat was to operate the two bomb bays located in the center of the aircraft and drop their contents over enemy territory. Theodore—surely he had a nickname, such as Ted—belonged to Component Six of the U.S. Army, which indicates that he was possibly in the National Guard prior to being drafted. He, too, was single with no dependents.

Wilfred J. Koehn

The ship’s navigator was 2nd Lt. Wilfred J. Koehn, service number O-795263. Born in Illinois in 1919, he had two years of college and was working in Cook County as a shipping and receiving clerk when, in January 1942, he enlisted in Chicago and went directly into the Army Air Forces. A bachelor like most of his fellow crewmembers, he was 25 years old when he calculated the coordinates for the sweeping arc toward the English Channel and home, which brought the B-24 into range of the German flak coming from the ridge above Rouxmesnil-Bouteilles.

Robert E. Hagey

One of the crewmen, the radioman and left waist gunner, was Staff Sergeant Robert E. Hagey, service number 15103517. Records show that he lived at 738 Cottage Grove Avenue, South Bend, Indiana.

Information obtained from Bob Schreiner, Hagey’s nephew, includes the last three heartbreaking letters sent home from Robert Hagey in England. He tells his mother Matilda about being off in a “rest home” with his fellow aviators (likely a recreational leave) and how nice it was to relax. He consoles his mother on the very recent loss of her husband Alvin, his father, and hopes that she knows that Dad wouldn’t have wished to linger long being ill. Bob suggests that mom use his own “nest egg” if she needs anything.

In his very last letter, written on February 4 from his base in England, Bob writes that although he’s close to reaching his quota of 25 missions bad news has just arrived on base, pushing back hopes of getting home as soon as previously planned. Bob writes to his mother with the assurance that everything is going to be fine, although he expects those last four missions to be tough, “The longest and hardest of all, from a mental standpoint.”

Mrs. Hagey received a War Department telegram sent on February 26, informing her that Bob was missing in action. It was not until July 16, 1944, that his mother received the confirmation telegram that Bob had indeed perished over France—an awful wait that resulted in the tear stains on Bob’s last letter dated February 4, just a week before the crash.

Willis D. King

Staff Sergeant Willis D. King, service number 14005640, was the ball-turret gunner. He was born in Florida and at the time of his enlistment was living in Leon County, yet he enlisted in Montgomery, Alabama. Did he, while traveling, enlist on a whim? Probably not, as he had originally enlisted to participate in the Philippine Department in the regular Army in August 1940.

Of all 10 crew members, Willis had the longest Army experience as he had volunteered 16 months before America’s official entry into the war. He was single, 22 years old with three years of high school behind him, and had been working as an office clerk/messenger boy before enlisting. Immediately he was assigned to the Air Forces, yet how did he end up at Hardwick instead of the requested Philippine Department? We do know that Willis King was the ball-turret gunner, which had to be one of the most terrifying positions in a World War II bomber.

Mitchell W. Powell

The radio operator, Technical Sergeant Mitchell W. Powell, service number 38181478, joined the Army in August 1942 at the age of 25. He left behind a wife and extended family. Mitchell’s nephew, Otto McCurdy, remembers his uncle well. Otto explains that Uncle Mitchell was a soft-spoken young man who loved to play ball with him and his brother. Otto remembers the proud day he was ring bearer at Mitchell and Pearl’s wedding. In the eyes of his young nephews, Mitchell was a larger than life hero—flying planes and participating in dangerous missions to save the world from the Nazis.

Otto also remembers that Mitchell was the baritone in a gospel music quartet that included other members of the family; Aunt Pearl played the piano for the group. Mitchell was listed as a farmhand in Gotebo, Oklahoma, with no further education than grammar school. Yet, on February 11, 1944, less than two years after enlisting, he had achieved the rank of technical sergeant, which says something about the aptitude of this young man.

Otto McCurdy recalls one specific Sunday dinner after church at his grandparents’ farm when the mailman drove seven miles out from town on his day off to deliver a telegram bearing the news of the crash. Otto was nine years old, but he doesn’t remember much of the rest of that Sunday dinner, which melted into tears of heartbreak.

Herbert J. Garrow

Counix, New York, was the hometown of Staff Sergeant Herbert J. Garrow, service number 32551821, the tail gunner on the Lonesome Polecat. A bachelor with just two years of high school education, Garrow worked in a machine shop until age 21, when he was drafted into the Army.

Garrow’s sister-in-law, Elinor, recalled that he was “ever the gentleman,” once insisting on making a long detour in order to see her safely on the bus home after accompanying her on a visit to her husband—Herbert’s brother—in training camp one day in August 1942 at Fort Niagara. That “fun” day was the last one the two brothers spent together.

Training in a machine shop might prepare one to use the machine gun inside the tail of the B-24, but what discipline could prepare the human body for the cramped position Herbert adopted for hours on end, firing at enemy aircraft? One can only hope that Herbert Garrow was a small man and that he had the flexibility of a ballet dancer; it must have been miserable. Twenty-five missions later, Garrow squeezed himself into position for a final flight, which ended when the tail of the Lonesome Polecat broke off and careened down the side of a ridge into the heart of the village quite near the horse racing track.

Clifford A. Stafford & Ruel K. Boone

The two remaining crewmembers remain somewhat of an enigma. Little information about Technical Sergeant Clifford A. Stafford, service number 37211296, is available. He is listed as the top turret gunner and as the mechanical engineer. Clifford’s hometown is given as Thayer, Kansas. Even less is known about Staff Sergeant Ruel K. Boone, service number 6923409, the right waist gunner, whose home town was Fort Hill, South Carolina.

A Crew With a History

Flying men were a breed apart from foot soldiers, and they did everything in their power to keep it that way. An undeniable prestige accompanied the risks taken on every single mission. Unlike their counterparts on the ground, air crewmen were called into action with little or no warning and with a recurrent frequency, leaving little time for kicking back and relaxing.

When they did find the time for a beer, they most often stuck together, downing their brews in the familiarity of their own company. Fate pushed fraternity to the extreme when the men of the Lonesome Polecat died together at 9:54 am on a Friday morning in February.

The men of the Lonesome Polecat in particular had history as a group. They had been among those singled out to support the Allied invasion of Sicily in the summer of 1943. They also participated in the successful low-altitude raid on the Romanian oil refinery at Ploesti, helping to win a Distinguished Unit Citation awarded to the 93rd. In September 1943, they returned to Italy to support Operation Avalanche, the invasion at Salerno.

Upon their return to Hardwick they were assigned regular raids on factories, oil refineries, and other strategic targets in occupied France, Belgium, and the Netherlands and in Germany. In all, some 25 missions were completed by the 10 airmen making up the crew of the Lonesome Polecat.

Fate of the Lonesome Polecat

When the squadron flew above Rouxmesnil-Bouteilles, they were flying above thick cloud cover: 80 percent at just 3,000 feet. The rest of the squadron never saw the town beneath them. They didn’t see the German 88s until their shells burst in ugly black puffs above, below, and around them. Nor did they see the Lonesome Polecat crash to the ground.

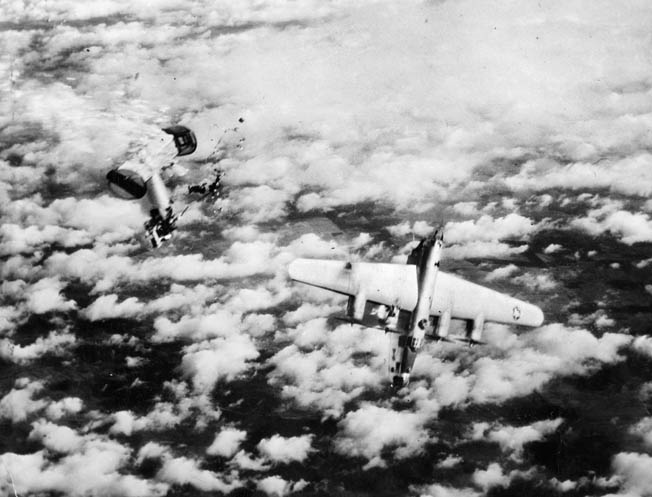

The report by one of the other pilots in the squadron states that the Lonesome Polecat took a direct hit from flak in the area of the right lateral porthole. The tail separated from the body of the plane while the rest plummeted to the ground. No parachutes were seen.

What other members of the squadron did see was more horrific than one can imagine today. They saw Lonesome Polecat take a hit, break in two, and the body of the right waist gunner, Staff Sergeant Ruel K. Boone, violently exit the aircraft and hurtle into the fuselage of one of the other planes below and behind.

The German gunners manning the 88s didn’t see the B-24s, but they could hear them coming. They fired on the squadron, targeting different altitudes to increase the chances of hitting one of them. The fact that they actually hit a B-24 was a stroke of sheer luck.

A thunderous explosion was heard in the heart of the village of Rouxmesnil-Bouteilles, an explosion louder and more terrifying than any other noise anyone there had ever heard. When they were done firing at the unseen airplanes above them, the German gunners went down into the village to see exactly what had happened. A mass of unrecognizable debris greeted them—bricks, plaster, bits of furniture, a piece of an airplane, an engine, and a wheel. Civilians were picking through the charred ruins of what had once been a house, and the Germans pitched in to help.

The Germans dismantled the crushed home of Jeanine and Raymond Leconte, located near the factory workers’ gardening plots. Nearby they found the body of Staff Sergeant Boone. The Germans buried him along with his nine comrades in the municipal cemetery, where they remained until the end of the war. They also buried the young couple near the Americans.

The Germans and the townspeople marveled at how close the falling airplane had come to hitting the school and the children in it. Luck had intervened again—bad luck for some and good luck for others.

Burying the Men of the Lonesome Polecat

Most of the Lonesome Polecat crewmembers were reburied after the war at the American Military Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer on the bluff above Omaha Beach. Captain Omar A. Turner’s final resting place is there, in Section D, Row 18, Plot 30. Co-pilot and aspiring actor Hubert Tardif was buried in the same cemetery in Section A, Row 17, Plot 32.

Radio operator Technical Sergeant Mitchell W. Powell, along with the other crewmembers, earned a Distinguished Flying Cross on the Ploesti mission and is buried in Section A, Row 4, Plot 23 of the American Military Cemetery at Colleville-sur-Mer. He was posthumously awarded the Air Medal with three oak leaf clusters and a Purple Heart, as were most of the rest of the crew.

Ball-turret gunner Staff Sergeant Willis D. King is buried in Section B, Row 23, Plot 13 at the American Military Cemetery in Colleville-sur-Mer. He rests not far from Technical Sergeant Clifford A. Stafford—Section B, Row 19, Plot 5. Staff Sergeant Ruel K. Boone, who was ejected from the Lonesome Polecat, is in the same cemetery, in Section D, Row 20, Plot 32.

Bombardier 2nd Lt. Ted Olson’s remains were sent home to Minnesota to rest eternally at Fort Snelling National Cemetery in Minneapolis-St. Paul. Likewise, navigator 2nd Lt. Koehn’s remains were returned to the United States to be interred at Rock Island National Cemetery, Illinois. Staff Sergeant Robert E. Hagey, the left waist gunner, was buried in South Bend, Indiana. Tail gunner Staff Sergeant Herbert J. Garrow’s remains were buried at a cemetery in upper New York State.

The Crew Immortalized

It is stories such as these that are the small tiles that make up in the larger mosaic of World War II. The stories of the individuals resting beneath the pristine white marble crosses remain largely untold, especially in cases where an entire crew fell together with no survivor to tell the real story of who they were, what they talked about, and to describe the group dynamic of the men who manned the Lonesome Polecat.

However, despite the lack of these details, the people of the village of Rouxmesnil-Bouteilles gather every year on February 11, when invariably the weather is grim. They assemble at the town hall, the elected officials wearing their tri-colored sashes, former military men squeezed into uniforms pulled out of closets for the occasion, the elderly who remember the day they were in class and heard a terrific crash, and the children who attend the very same school today.

This makes up quite a lengthy procession with traffic being halted on the main street. They solemnly cross the road and walk the 200 yards to the crash site on the Rue des Jardiniers, now decorated with a granite monument. The names of the 10 American airmen are inscribed on the monument along with the names of the two civilian casualties. They are among the more than 30,000 U.S. Army Air Forces airmen who perished or went missing in the European and Mediterranean Theaters during the campaign to defeat Nazi Germany.

The mayor stands beneath the two flagpoles, one flying the French flag and the other the American flag. He gives a nice speech indeed, sincerely thanking the Americans who came from so far away to defend his right to be free. He also thanks the Americans of today, who have lost their uncles, husbands, brothers, cousins, and grandfathers for the sacrifice made every day, for the loss of all the Christmas dinners, birthdays, weddings, and family events they can’t share with the men who stayed behind in France, and in all of Europe.

The French, the people of Normandy in particular, do not allow themselves to forget that the price of their peace was paid for largely by men they know so little about, and who knew nothing of them.

The people of Rouxmesnil-Bouteilles hope that when they try to sing “The Star Spangled Banner” each February 11 that the people of the United States of America can find it in their hearts to forgive the somewhat garbled version heard coming from the crowd gathered near the crash site of the Lonesome Polecat.

Thank you so much for this story. Mitchell Powell was my great uncle. I had no idea of the conditions of the loss or the continued rememberance in France.

Thank you for this story! Most Americans have no idea of the sacrifices made by the military in times of War!

How many Americans knew that 30,000 (Thirty Thousand!) American airmen died in WWII! Then, add to that number those from the Army, Navy and Marine Corps who perished!! Thank you to all who gave their all for us remaining!

Thank you so much for this little piece of history, giving us a small glimpse into the lives of those who gave all so that we could be free. I am honored to have been able to follow in their footsteps, serving our great country during the Cold War. Thank you again for this article.

Thanks so much for this story. Ruel Kenneth Boone was my great uncle.

Thank you for this history. Small correction regarding Herbert Garrow… He was not a bachelor. He was married to my maternal grandmother, Clarice Ross, in Niagara Falls on June 22, 1943, before leaving for duty. She remarried after the war. My grandfather and her eventually separated. My great-aunts spoke fondly of Herbert and described him as the love of Clarice’s life. We have always remembered and honored Herbert as a member of the family though we are not biologically related.

Ruel Kenneth Boone was my Uncle as well as Alan Clayton’s uncle. We are going to Normandy in a few week to attend the Memorial to the crew and the couple who died. Thank you to all the wonderful French people who do not forget and honor our loved ones.