By Tim Miller

In November 1944, a young American soldier wrote back to his parents in the Washington Heights neighborhood of Manhattan. Six years earlier, he and his family had fled Germany for the United States, only weeks before Kristallnacht, the infamous Night of Broken Glass.

Now here he was, having returned to the place where, had they stayed, he and his family may well have already perished. “So I am back where I wanted to be,” the young man wrote. “I think of the cruelty and barbarism those people out there in the ruins showed when they were on top. And then I feel proud and happy to be able to enter here as a free American soldier.”

Long before his stint as yet another Harvard intellectual; long before he was thought to be the inspiration for Stanley Kubrick’s Dr. Strangelove; long before his advisory roles in the Kennedy and Johnson administrations and support for Nelson Rockefeller’s bids for the presidency; and long before he became President Richard Nixon’s Secretary of State and, by turns, was either one of the most admired men in the country, or condemned as a war criminal—Henry Kissinger was a recent immigrant serving in the United States Army. But it was his experience in the war—without which he may have merely ended up as an accountant—that made him.

As he later wrote, “High office teaches decision making, not substance. It consumes intellectual capital; it does not create it. Most high officials leave office with the perceptions and insights with which they entered; they learn how to make decisions but not what decisions to make.” The man who became so respected or reviled, and who was said to be “musically attuned to history,” became so by witnessing history, including the Holocaust, firsthand.

Born in 1923 in the Bavarian town of Fürth, Kissinger later dismissed the notion that life in the crumbling world of Weimar amid the temporal triumph of Nazism affected his childhood much before the moment he and his family left for America. “I wasn’t concerned with the international system,” he said. “I was concerned with the standing of the football [soccer] team of the town in which I lived.”

The year of hyperinflation in 1923, left the German mark amazingly worthless (one trillionth the value of a prewar mark). It was also the year of Hitler’s failed beer hall putsch. The combination of inflation, depression, and the need for a scapegoat for the country’s woes, a scapegoat whose wealth and cultural influence far outstretched the small percentage they made in the population, all found their way to Fürth as well. Hitler visited the city in 1925, with Der Stürmer editor Julius Streicher alongside him. According to the odious newspaper, the city was a “citadel of the Jews” and where the future Führer lamented how Germans had become “slaves of Jewry.”

On March 9, 1933, the Nazi party in the city held a torchlight parade, where the 12,000 or so who gathered watched the Nazi flag raised outside the Rathaus and heard a speech which declared, “Today marks the beginning of the great clean-up of Bavaria…. Even Fürth, which was once red and totally jewified, will once again be made into a clean and honest German town.”

On May 10-11, 1934, as across all of Germany, whether in cities or universities, a bonfire of subversive books lit up the Fürth sky, while the previous April, Kissinger’s father, as well as any Jews in the Civil Service, were fired from their jobs and Jewish children were forbidden to attend non-Jewish schools.

Many of Kissinger’s relatives had already left Germany by 1938, dispersing to Palestine and Sweden, as well as the United States. In October 1937, a cousin of Kissinger’s mother, living in Westchester County, New York, pledged to financially support the family should they emigrate, and seven long months later, in May 1938, approval from everyone—from U.S. officials down to the mayor of Fürth—had been secured. Passports were issued. Leaving behind nearly everything they owned, including most of their savings, as well as his mother’s ailing father, by late August Kissinger and his family sailed for England, and finally for New York City, and not a moment too soon.

Thanks to the meticulous records kept by the Nazis, the fate of the Jews of Fürth, as of many cities and villages, is known with great accuracy. The city’s Jewish population was nearly 2,000 in 1933. Of those who did not emigrate, only 40 survived the war. The number of dead among Kissinger’s relatives as a result of the war, in Fürth and elsewhere, is estimated between 30 and 60.

Kissinger and his family landed in the United States at an inopportune moment, amid the so-called “Roosevelt Recession” in which, beginning in the middle of 1937, the national unemployment rate had slowly risen to nearly 20 percent. In the year when the most popular movie was Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, America was still in the grips of the Depression, which Germany had already climbed out of. As H.G. Wells’s War of the Worlds radio broadcast sent people into a panic that October, the theories of American eugenicists were also still in vogue. Irish Christians, suspicious as ever of how successful Jewish immigrants and businessmen had become, derided the “Jew Deal,” while a poll conducted in 1939 by Fortune magazine found that nearly 90 percent of Catholics and Protestants (and 26 percent of Jews) would have voted “no” on letting in European refugees beyond the number currently allowed by law. Even Franklin Roosevelt, asked specifically about the fate of Europe’s Jews after Kristallnacht, was clear: “We have the quota system.”

The fear of a “Jewish menace” and an “alien menace” led to widespread support for the self-styled “American Hitler,” William Dudley Pelley, as well as the Catholic priest Charles E. Coughlin, whose weekly radio show attracted more than 30 million listeners. Coughlin was especially unapologetic in his anti-Semitism, and his National Union for Social Justice (an Orwellian name if ever there was one) was happy to publish the fraudulent Protocols of the Elders of Zion to prove his point. Beyond even Coughlin were groups like the Christian Front and the Christian Mobilizers, and the Freunde des Neuen Deutschland, or the German-American Bund, America’s largest pro-Nazi organization, headquartered in New York City in the Yorkville neighborhood on the Upper East Side.

Yet not too far north, in the neighborhood of Washington Heights, such a large Jewish community flourished, especially made up of German-Jewish refugees, that it was dubbed the Fourth Reich. It was here that the Kissingers set to assimilating, with Henry now learning baseball and batting averages, and with English being learned at home mostly from the radio. Despite the existence of American anti-Semitism, it was clearly of a different stripe, and overall America clearly offered a different life. As Kissinger remembered later: “When I was a boy it was a dream, an incredible place where tolerance was natural and personal freedom unchallenged…. Seeing a group of boys [walking down the street], I began to cross to the other side to avoid being beaten up. And then I remembered where I was.”

Attending George Washington High School, Kissinger’s options were either to learn English quickly or fall behind. While he had learned enough English back in Germany to at least read it, sounding and becoming American was the problem. He also began attending high school at night, after he took a job at a shaving brush factory during the day to help make money for the family. Yet he flourished, and it was not long before he had the time and command of the language to read Dostoevsky in English.

While admitting that his future lay in America, and while planning to attend the City College of New York and become an accountant, the gulf that separated him from Americans in general was still not lost on Kissinger. For while they certainly were not blind to social injustice, there was still a sense of ease and materialism and superficiality that he did not understand. “The American trait I dislike the most,” he wrote, “is their casual approach to life. No one thinks ahead further than the next minute, no one has the courage to look life squarely in the eye, difficult [things] are always avoided. No youth of my age has any kind of spiritual problem that he seriously concerns himself with.”

While there may be some accuracy here, these words also clearly reflect a personal experience of upheaval and change few of his peers could fathom. And so it is not such a surprise that anyone, let alone a teenager already in flux, and one who admitted that “95 percent of my previous ideas have suffered shipwreck” should feel isolated and alone. But with the entry of the United States into World War II that was about to change.

News of the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor came while Kissinger was at an (American) football game, back when the New York Giants and Brooklyn Dodgers were also the names of football teams. “I didn’t know where Pearl Harbor was,” he admitted. At the time, however, Kissinger was both too young to be conscripted and not yet a naturalized citizen. By the end of 1942, the conscription age was lowered to 18, and after three months of basic training at Camp Croft, South Carolina, he became a naturalized citizen. Like others of the nearly 10,000 German-Jewish refugees who served America in the war, part of his oath included renouncing his allegiance “particularly to Germany, of whom I have heretofore been subject.”

The only segregation remaining in the armed services at the time was between whites and African Americans, and so Kissinger was thrown into the mix with young men he would likely have never encountered in Washington Heights. If, as the writer Irving Howe put it, the variety of New York City was “the embodiment of that alien world which every boy raised in a Jewish immigrant home has been taught … to look upon with suspicion,” how much more so was the U.S. Army?

Yet, Kissinger quickly made his mark and made friends, and it was more the daily regimen of Army life—and not any prejudice experienced there—that led to the later loss of his Jewish faith. As the phrase went, “Eating ham for Uncle Sam” became the rule of the day, especially when Kissinger was selected to be part of the Army Specialized Training Program (ASTP), which sent the smartest Army recruits to colleges all across the country for technical training and accelerated college courses. In early 1944, however, the program was cancelled, and all the “quiz kids” were scattered throughout the Army, Kissinger landing in G Company, 2nd Battalion, 335th Infantry Regiment. Having succeeded in the ASTP, Kissinger nevertheless blended right in with G Company as well, young men mostly from the Midwest. “I found that I liked these people very much,” he said. “The significant thing about the army is that it made me feel like an American.” The other men took to him as well, and when he was made the company’s education officer, he gave weekly lectures about the state of the war and troop movements.

By September of that year, Kissinger and his fellow soldiers were sailing for Europe; in early November they crossed from England and landed on Omaha Beach, still littered with the debris from D-Day. Barely three weeks later, surely a testament to the British and American soldiers who had come before them, G Company was already in Germany. This was where Kissinger wrote back to his parents, not wanting to miss the moment where he could begin with the words, “Somewhere in Germany.”

“Somewhere” soon became the Battle of the Bulge, and Kissinger’s letters home about the mud in Germany that “crept into your hair, your food, your teeth, your clothes and sometimes your mind,” soon became complaints about the ice and drinking water out of mud holes and tank tracks. He described the firing of German machine guns “like a curtain tearing,” and it was around this time, amid a company that suffered proportionally high casualties, that he was promoted to special agent in charge of the regimental Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) team. Kissinger took to this work immediately, rounding up and evacuating German civilians “considered unreliable,” and poring through mail and paperwork left behind. In one town, where he described people living “in houses with cardboard in place of windows, with quagmires instead of streets,” he could nevertheless also remark, “Germany now knows what it means to wander and to be forced to leave places dear to one’s heart…. It is tragic no matter how [much] you hate the Germans.” He also added: “They are not mistreated. We are no Gestapo.”

By March 1945, however, with the 84th Division now in the city of Krefeld, many of whose civilians still remained, the difficulties of prioritizing the work of an occupying force, which would consume thousands of minds in the years to come, began to show itself. Was it, for instance, the job of Kissinger and others to restore relative order and local administration of the town, or (still with VE-Day unknown and in the future) was it necessary to put such goals aside in favor of finding and arresting career Nazis and separating them from those who had passively gone along? For a time, the latter became a priority, which also meant assessing the full sympathies of the local population to the Nazi regime, many of whom could not be detained but had nevertheless lived with Nazi propaganda for so long.

As Kissinger wrote in a CIC report, “For twelve years the Nazis have had a stranglehold on those in public office. Officialdom and Nazism have, as a result, become almost synonymous in the public mind. It becomes the duty therefore of the occupying authorities to clean the city administration of these cliques of Nazis.” Such a job was ideal for Kissinger, who could speak the language, and whose psychological insight into the enemy was already keenly perceptive.

Kissinger’s Jewishness also came into play: his dog tag identified his religion, and if captured he undoubtedly would have been killed immediately, as had happened to German-Jewish interrogators taken in early 1945. Kissinger would also have been aware that, of the 800 or so Jews that had lived in Krefeld before the war, only four remained, the rest having emigrated or been rounded up. And it was on April 10, 1945, that he came to witness what nothing, not his childhood experiences of anti-Semitism in Fürth, not his knowledge of the nightmare of history, not the hell of battle and the closeness of death, could have prepared him for. Even the words of his Rabbi in 1942, who had also fled Fürth for Washington Heights, describing “unimaginable mass murders” carried out against Jews, could have meant much to seeing it firsthand.

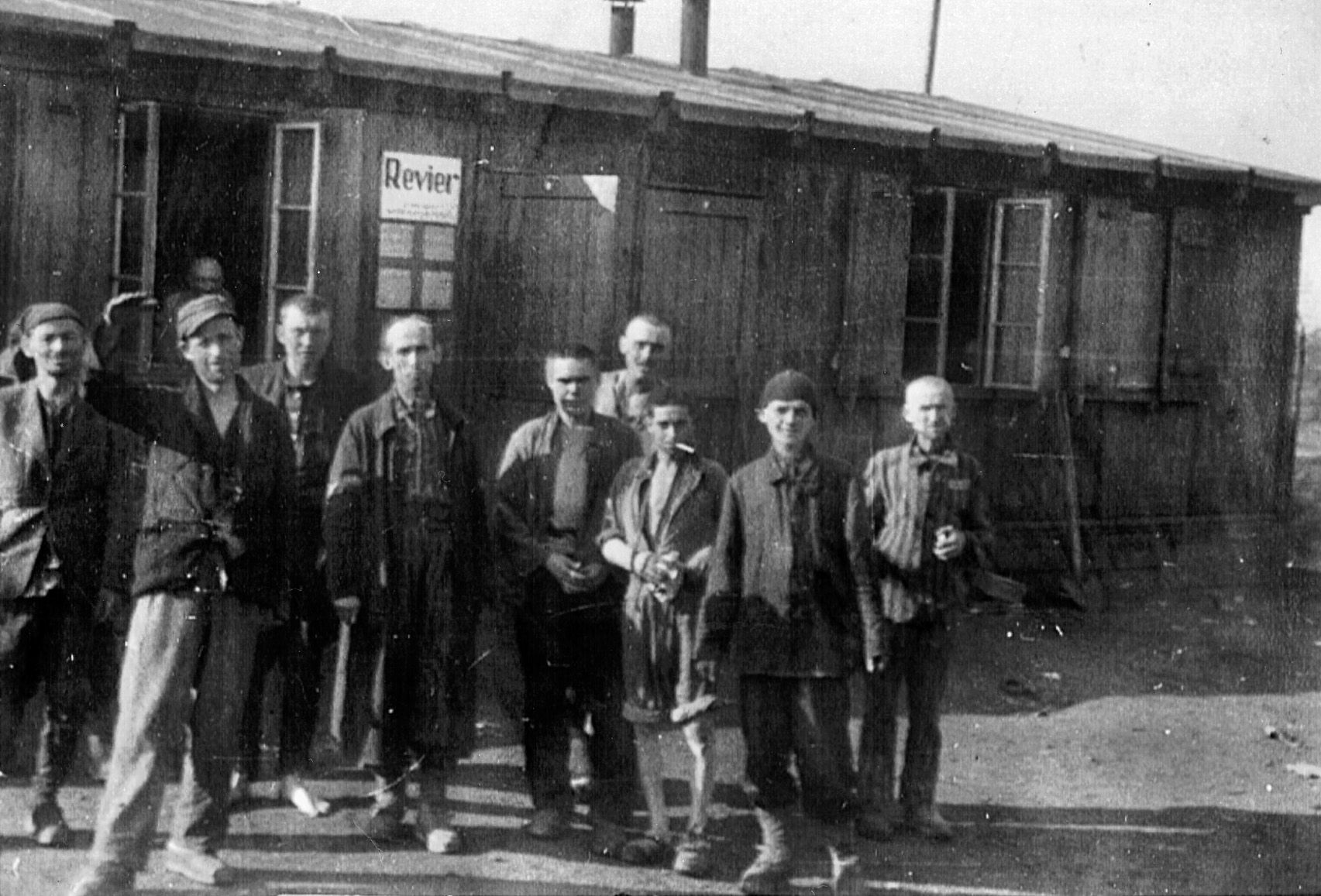

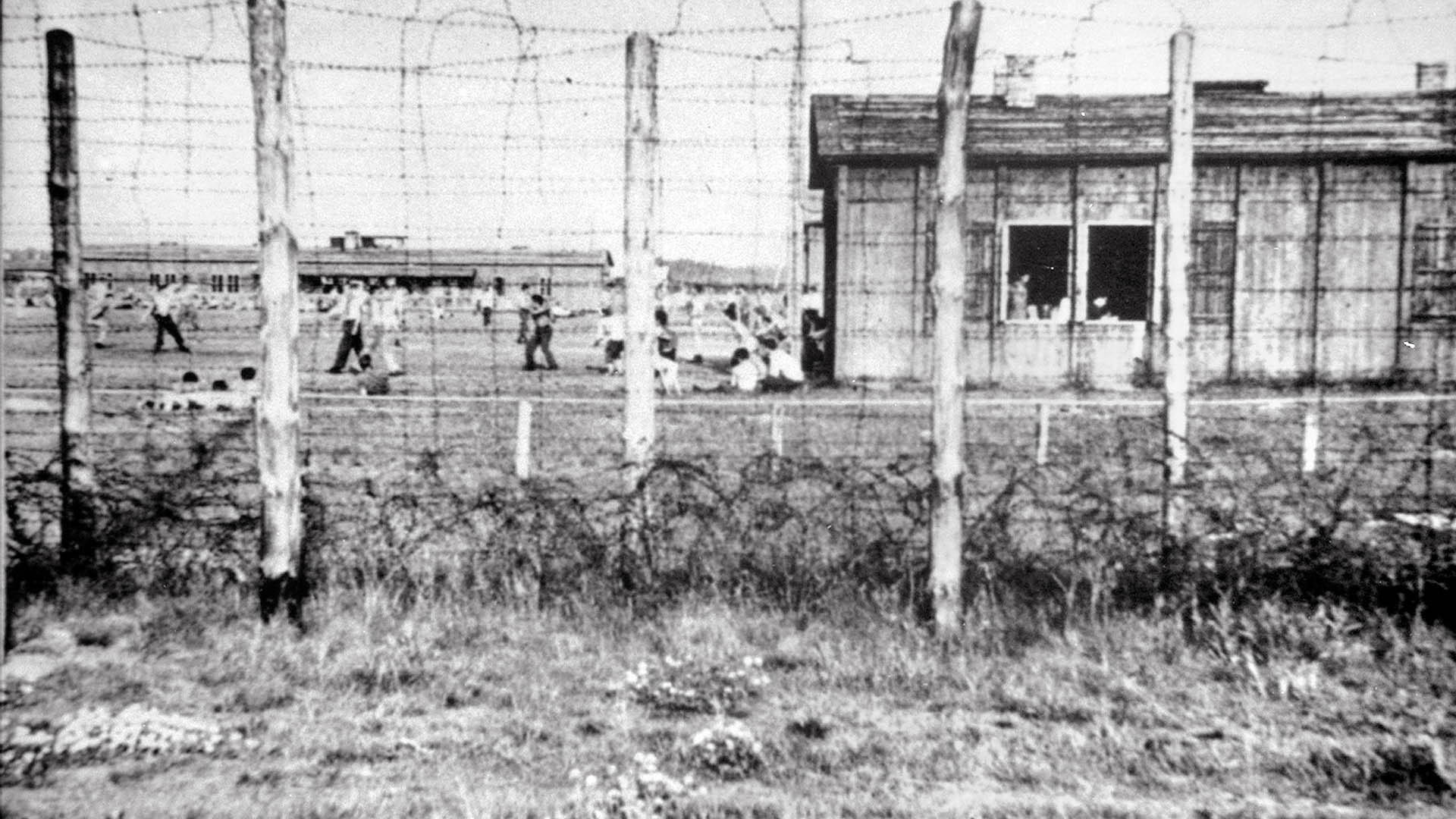

While a labor rather than a death camp, and with only a handful of barracks, when Kissinger and the rest of the 84th came upon the concentration camp at Ahlem, they found hell in miniature. Perhaps at the now more well-known camps it was possible to even get lost or awed by the scope of death and destruction; this was not possible at Ahlem, located only a few miles west of Hanover, where every detail was near at hand. By January of that year, some 600 out of a total of 800 prisoners were still alive, and in early April all but 200 or so were force marched to Bergen-Belsen. Those who stayed behind were too sick to make the journey, and they would have been murdered and the complex destroyed but for the swift advance of the Americans. We only know Kissinger was there thanks to a fellow soldier, Vernon Tott, who long after the war published the photos he took at Ahlen. Only then did Kissinger admit to “one of the most horrifying experiences of my life.”

Images that have become so familiar by now lay before these men in the flesh, close enough to touch, as indeed many of them were: emaciated corpses everywhere, indoors and out, stacks and piles of them, and a mass grave holding hundreds more. Tott remembered a young man they came upon in one of the barracks: “[T]here was a boy, about fifteen years old, who was lying in his own vomit, urine and stool. When he looked at me, I could see he was crying for help…. Our troop had just come through six months of bloody battle but what we were seeing here made us sick to our stomachs and some even cried.”

Another recalled: “The war will probably fade from memory, but those were the most pathetic human beings I have ever seen or hope to see in my whole life.” They also found “huge bull whips as well as some cat-o-nine tails,” and indeed one of the survivors mentioned how the SS guards frequently beat them: “They seemed to like to hit us.”

Soon after the liberation of Ahlem, Kissinger wrote a never published reflection called The Eternal Jew, repurposing the title of a Nazi propaganda film to make a different point entirely. In part, it reads: “The concentration camp of Ahlem was built on a hillside overlooking Hannover. Barbed wire surrounded it. And as our jeep travelled down the street skeletons in striped suits lined the road. There was a tunnel in the side of the hill where the inmates worked 20 hours a day in semi-darkness.

“I stopped the jeep. Cloth seemed to fall from the bodies, the head was held up by a stick that once might have been a throat. Poles hang from the sides where arms should be, poles are the legs. ‘What’s your name?’ And the man’s eyes cloud and he takes off his hat in anticipation of a blow. ‘Folek … Folek Sama.’ ‘Don’t take off your hat, you are free now.’

“And as I say it, I look over the camp. I see huts, I observe the empty faces, the dead eyes. You are free now. I, with my pressed uniform, I haven’t lived in filth and squalor, I haven’t been beaten and kicked. What kind of freedom can I offer? I see my friend enter one of the huts and come out with tears in his eyes: ‘Don’t go in there. We had to kick to tell the dead from the living.’

“That is humanity in the 20th century. People reach such a stupor of suffering that life and death, animation or immobility can’t be differentiated anymore … Folek Sama, your foot had been crushed so that you can’t run away, your face is 40, your body is ageless, yet all your certificate reads is 16. And I stand there with my clean clothes and make a speech to you and your comrades.

“Folek Sama, humanity stands accused in you. I, Joe Smith, human dignity, everybody has failed you. You should be preserved in cement up here on the hillside for future generation[s] to look upon and take stock. Human dignity, objective values have stopped at this barbed wire…. As long as conscience exists as a conception in this world you will personify it. Nothing done for you will ever restore you. You are eternal in this respect.”

Kissinger remained in Germany until 1947, long after he could have returned home. Writing back to his family in the United States who wished to see him, he said, “I agreed that no matter what happened, no matter who weakened, we would stay to do in our little way what we could to make all previous sacrifices meaningful. We would stay just long enough to do that. Continuing to work with CIC (also in the ranks was author J.D. Salinger), he helped both transition intelligence focus to the Soviet Communist threat and continuing to round up fugitive Nazis and make more pragmatic judgments about other Germans who also remained.

“We have not come here for revenge,” one of Kissinger’s secretaries recalled him saying, and indeed the complexity of these events lies in a small anecdote. One of the SS guards at Ahlem was Otto Harder, and while he did serve time in prison after the war, it is disturbing that his Wikipedia page today is more about his career as a professional soccer player.

It was “shocking incongruities” like these that faced Kissinger then, and which seem to have defined his life ever since. And whether in Ahlem, or slowly along the way during his time in the army, Kissinger lost his religious faith. On the one hand he did make the familiar point, “There was also the argument that in a world where one’s relatives are burnt to death, there could be no God.” But the experience of absolute horror carried with it the knowledge that, one might say, the world has to go on, not every perpetrator will be punished, not every murdered man or woman will be avenged, and life from then on will be compromised somehow.

Such realities also seemed to preclude anything like the God he had believed in as a child. These words he wrote to his parents must indeed have shocked them. “To me there is not only right and wrong but many shades in between…. The real tragedies in life are not in choices between right and wrong. Only the most callous of persons choose what they know to be wrong. Real tragedy comes [illegible] in a dilemma of evaluating what is right…. Real dilemmas are difficulties of the soul, provoking agonies, which you in your world of black and white can’t even begin to comprehend.”

Yet he also made time to visit Fürth, making sure his grandfather’s grave there was the “best kept in the cemetery.” He also took in a soccer game at the old stadium. “Fürth lost and the referee got beaten up, which was standard practice,” he wrote. “The German police couldn’t rescue him, so the American military police came up and recused the referee, and one guy sitting down next to me got up and yelled, ‘So that’s the democracy you guys are bringing us!’”

To have sat in the very stadium he had once been forbidden by law to enter and to know that in part his actions had made such a day possible, indeed possible enough to tell a funny story from his old hometown, provided him with some satisfaction. “I am usually not smug or self-satisfied,” Kissinger wrote, “but in Fürth yes.”

Author Tim Miller last wrote for WWII History on the spy network in occupied Paris. He resides in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments