By John J. Domagalski

General Alexander Patch had been thinking about moving some troops to the southwestern part of Guadalcanal since taking command of all American ground forces on the embattled island on December 9, 1942. Little more than a month later his soldiers were cautiously pushing the remaining Japanese troops on the crucial island in the Solomons chain toward its western tip. The general was certain Japanese resistance would soon be near collapse—unless the enemy somehow received reinforcements.

It was a culmination of months of vicious fighting. American Marines had first landed on the island the previous August, touching off a bitter struggle for control of Guadalcanal and the surrounding waters. American forces had only recently gained the upper hand after a series of land, sea, and air battles that engulfed the Solomon chain in the South Pacific. Opposing naval and air units clashed regularly in Iron Bottom Sound, a body of water between Guadalcanal and the nearby islands of Tulagi and Savo, as the Imperial Japanese Navy attempted to resupply its island garrison through speedy voyages under the cover of darkness from bases farther north. The Americans commonly labeled the night supply runs the Tokyo Express.

The last days of January 1943 found Patch’s troops advancing west along a coastal plain on the northern side of the island. The remaining Japanese troops were falling back toward Cape Esperance at its northwestern tip. The area was known to be a key dropoff point for the Tokyo Express.

To help prevent the possibility of the Japanese prolonging the battle with reinforcements, Patch wanted to land troops on the southwest portion of the island, directly south of Cape Esperance. It would be a classic flanking move to force the Japanese to face advancing Americans on two fronts. This particular area of Guadalcanal was not thought to be heavily occupied owing to the thick jungle and mountainous terrain.

The operation, however, required help from the Navy. A similar plan had been on the table months earlier but was cancelled due to the lack of available seaborne transport. The needed naval forces were now available. The mission would put a brand new American destroyer in harm’s way.

When the Fletcher-class destroyer USS DeHaven was launched before a small crowd at the Bath Iron Works in Maine on June 28, 1942, few onlookers expected that her service life would be short. The warship was the newest of many vessels being turned out monthly by American shipyards that were now fully mobilized to support the war effort. She bore hull number DD-469. Her namesake was Edwin Jess DeHaven, a Pennsylvania sailor who served with distinction during a long naval career in the mid-1800s.

She was commissioned into service September 21, 1942, under the leadership of Commander Charles E. Tolman. A period of intense training for the crew followed. The new destroyer measured almost 377 feet in length and displaced 2,800 tons. Armament consisted of five 5-inch guns in single turrets, 10 torpedo tubes, an assortment of smaller antiaircraft guns, and depth charges.

The new warship traveled south to Norfolk, Virginia, after completing some initial training and voyages in local waters. The bustling seaport had long been the bastion of American naval power on the Atlantic. DeHaven was soon earmarked for duty in the Pacific. She met up with a trio of new warships—battleship Indiana, cruiser Columbia, and destroyer Saufley—for the long journey.

Ensign Clem C. Williams, Jr., was aboard DeHaven from the start. “We spent one night there and started south,” he later said of the voyage out of Norfolk. “The next port we hit was Panama. We went through the canal and the next day set off for the broad Pacific.”

The trip across the Pacific was largely uneventful, except when the new destroyer made a botched attempt to refuel from the battleship. “It was the first time we had fueled at sea and we took a little too sharp an approach angle and rammed the Indiana and cleared off a couple of her stanchions on deck and punched a hole in the port side of the forecastle on our ship, which we patched up with mattresses, and sent to the Indiana for help in the way of a welding machine and some people who might be able to repair it,” Williams later recalled. “We were a long way from land at the time.”

The small convoy reached Tongatabu, Tonga Islands, on November 28, 1942, and proceeded to Noumea, New Caledonia, after only a short stay. “We all went ashore and ate a lot of coconuts, and we tried to find some beer but there wasn’t any,” Williams added. “We set off the next day.” Noumea was one of several forward operating bases used by the Navy during the ongoing battle farther north in the Solomon Islands.

The new destroyer was quickly pressed into service to escort a convoy of troopships to Guadalcanal. The precious cargo was Army soldiers set to relieve the Marines who had been there since the initial landings in August. “We were, of course, very excited about it and sort of scared, but the trip was fairly uneventful,” Williams explained. DeHaven screened the transports off the northern coast of Guadalcanal for about a week before returning south on December 14.

The warship supported the effort to secure Guadalcanal over the next month, operating from Noumea, Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, and Tulagi. The duty included regular night patrols in Iron Bottom Sound in search of the Tokyo Express, participating in two bombardments of Japanese-held Kolombangara Island in the central Solomons, and antisubmarine sweeps through “Torpedo Junction.” The latter region, an area of open water south of Guadalcanal, was known to be regularly patrolled by Japanese submarines.

“During all this period in the Solomons region, our personnel worked their radars and the sound was becoming more and more thoroughly indoctrinated, and we felt that our shakedown was finishing up in a way, but we never felt absolutely certain that we were a seasoned ship by any means,” Williams later said. The visit to the front lines was a type of on-the-job training since DeHaven was operating with some warships that had been in the area for months.

The men quickly became used to the regular Japanese air attacks on Guadalcanal. The strikes were often preceded by a “condition red” alert, an emergency radio broadcast from Guadalcanal indicating an attack was imminent. “We made a practice of keeping track of all the planes in the area as closely as possible. Our fire control party [had] orders to train the batteries on all unidentified planes until they were identified,” said Williams. The latter proved to be a difficult task as friendly planes of all types were flying in and out of Henderson Field, the main air base on Guadalcanal.

The holidays marked the waning days of 1942. “Christmas Day, unfortunately, was like any other day,” Williams later said. “We were in Torpedo Junction, and we all had to be on the lookout. We had our turkey dinner as usual, the same as the Navy has all over the world on that day, but outside of that, the day was pretty much a day of business.” There was no sign of the enemy as the destroyer sailed through clear weather conditions and hot tropical air.

Early January found DeHaven departing the front lines to escort a tanker from Noumea up to Espiritu Santo. A short stay in the New Hebrides port followed. “This time we sent a couple of swimming parties ashore and people went over to the [destroyer tender] Dixie, which had moved up to her base there, to have their teeth fixed and attend to a few routine matters,” Williams explained. He recalled that the ship had to be ready to depart within two hours around the clock as the situation around Guadalcanal could flare up at any time. “Most of the ships there are on very short notice and consequently you can’t plan on any protracted dental appointments, or you can’t plan on what you are doing tomorrow. We had no real liberty there.”

DeHaven received a new assignment during the middle of January when she joined the destroyers Nicholas, Radford, and O’Bannon to form Task Group 67.5. The group, under the command of Captain Robert P. Briscoe, was later expanded to five with the addition of Fletcher. It was to be stationed at Tulagi to provide close support in the Guadalcanal area. The small island, positioned directly across Iron Bottom Sound from Guadalcanal, was home to a good anchorage. Williams remembered Briscoe’s flag moving among various ships, including Fletcher, Nicholas, and O’Bannon.

Larger warships had not previously been permanently based at Tulagi owing to the continuous threat of air attacks. Cruisers and destroyers moved north from Espiritu Santo only as needed, often resulting in timing problems when trying to intercept the Tokyo Express. Briscoe’s vessels became known as the “Cactus Striking Force” after the American code name for Guadalcanal. The ships arrived on station on January 17, 1943.

The destroyers patrolled in the immediate area for the next two weeks conducting a variety of operations. The duty included shore bombardment in support of the advancing American troops on Guadalcanal, antisubmarine sweeps, and evening voyages to guard against the Tokyo Express. While operating with the Cactus Striking Force, DeHaven, Radford, Nicholas, and Fletcher were tapped to assist in General Patch’s plan to move troops to the other side of Guadalcanal.

The landing would be undertaken by the 2nd Battalion, 132nd Infantry Regiment under the command of Army Colonel Alexander George. The battalion was reinforced with various attached units, including four 75mm pack howitzers from the Marines. The force was large enough to accomplish the mission, but Patch wanted to avoid having the troops land at a defended beach. Little was known about the southwestern coastal area of Guadalcanal because the fighting had primarily taken place on the northern side of the island.

A small group of scouts was dispatched on a reconnaissance mission to gather intelligence. They ventured across the island on a jungle trail before boarding the small schooner Kocorana for a look at the coastal area in question. The men were able to identify several potential landing sites and establish a small observation post.

The last day of January found the area around Kukum full of activity. The coastal village, close to the site of the initial American landing on Guadalcanal, was serving as the debarkation point for the small amphibious operation. The soldiers along with trucks, equipment, ammunition, and supplies loaded aboard six small LCTs (Landing Craft, Tank) and the destroyer transport Stringham. The latter was an old World War I-era destroyer that had been converted to a fast troop transport. The vessels departed after the loading was completed at 6 pm.

Captain Briscoe’s four destroyers provided an escort as the small flotilla began its voyage around the western end of Guadalcanal. Daylight slowly turned into night as the month of January faded away. The destroyers Anderson and Wilson were set to bombard Japanese positions on the northern coast near the Bonegi River the next morning to create a small diversion.

Unknown to General Patch—even as his small amphibious operation was underway—the enemy was preparing to give up the fight for Guadalcanal. Japanese leaders in Tokyo had already approved an evacuation of the embattled island garrison. Local commanders were about to undertake a series of daring night operations to pick up soldiers near Cape Esperance. The first evacuation mission was slated to run on the night of February 1.

The voyage around Guadalcanal was uneventful for Briscoe’s flotilla. The forces arrived off Nugo Point at dawn on February 1. After an advance party went ashore in a small boat to confer with the scouts who had reconnoitered the area, it was decided the main landing should take place farther north near the village of Verahue. The landing began a short time later as friendly fighters appeared overhead to provide air cover.

A flight of Japanese bombers passed over the beach at about noon en route to bomb Henderson Field but did not attack. The destroyers opened fire, downing at least one plane. The coastal activity, however, warranted some additional Japanese attention. The destroyers were later reported as cruisers by a reconnaissance pilot—a potentially grave threat to the planned Japanese evacuation mission.

The unloading process near Verahue was nearly completed by early afternoon. “No opposition was encountered,” Williams later recalled of the landing. “We were prepared to give them fire support if they wanted it but they didn’t need any; they just didn’t run into anybody.” Three empty LCTs began the journey back around Guadalcanal at about 1 pm, escorted by Nicholas and DeHaven. The remaining ships, including Fletcher with Captain Briscoe aboard, stayed behind to wrap up the landing operation. The soldiers indeed encountered no enemy ashore and moved out from the beach area the next morning.

The retiring vessels became separated as the ships rounded Cape Esperance. “The DeHaven had gone ahead with the two leading LCTs and left behind the Nicholas,” Williams reported. The DeHaven group was about two miles southeast of Savo Island, with the remaining ships about five miles behind, when the enemy attacked from the air.

A condition red warning was issued by Guadalcanal at 2:43 pmfor Henderson Field. Seven minutes later a second broadcast reported enemy planes over Florida Island, directly across Iron Bottom Sound from Guadalcanal. DeHaven was circling the small LCTs at about 15 knots at the time. “The ship went to general quarters immediately and steered a course approximately northeast,” Williams reported. “Two more boilers were lighted off, but were not cut in.” The ship’s speed briefly increased to 20 knots before falling back to 15.

Lookouts sighted nine unidentified planes at 2:57 pm. The aircraft were about 25,000 yards off the destroyer’s starboard beam, heading in a westerly direction. Williams was at his battle station—a twin 40mm antiaircraft gun at the fantail. “I operated the director and directed the fire of the gun,” he said.

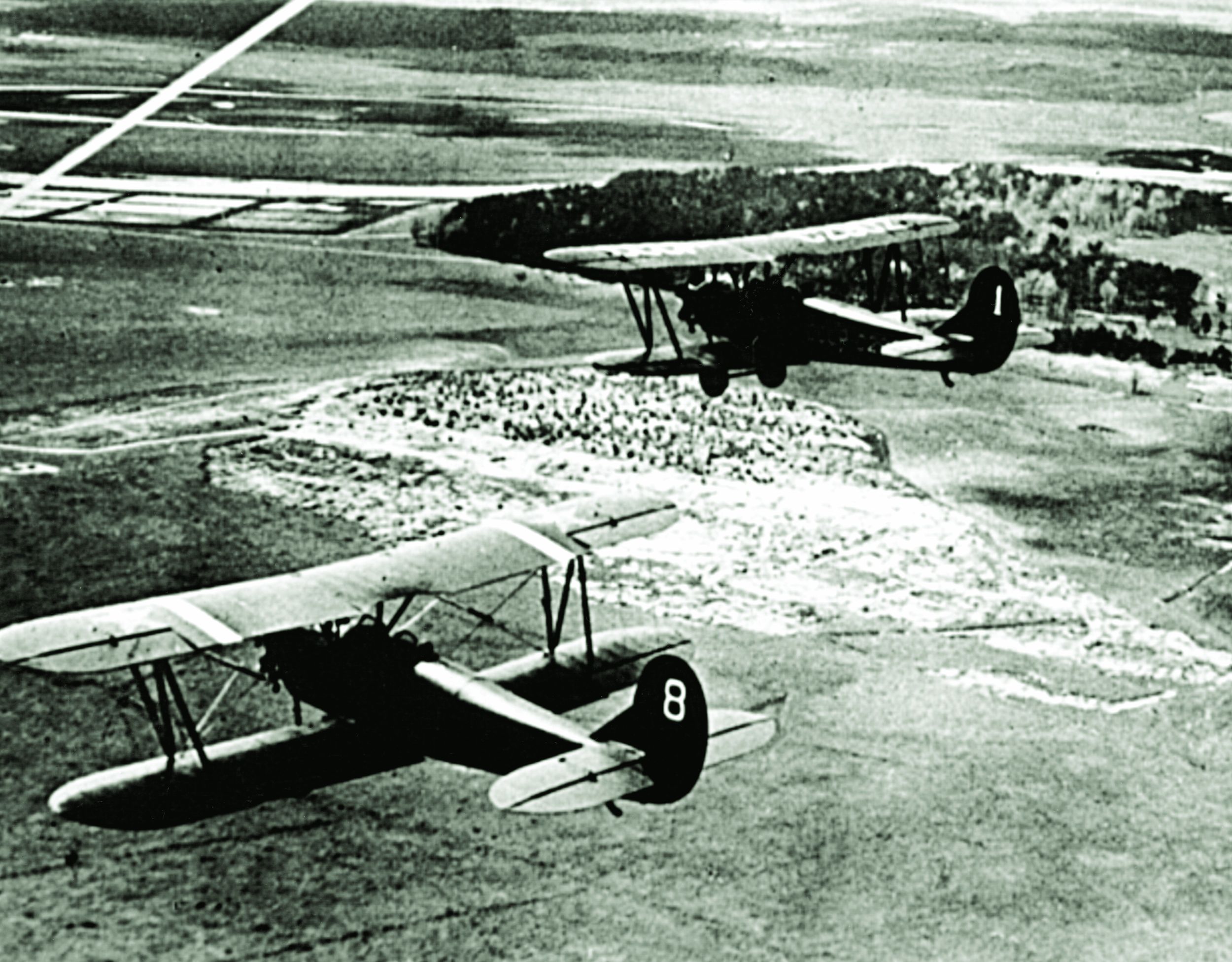

The planes were dispatched to deal with the American “cruisers” reported to be off Guadalcanal. The attack force had sortied with 15 Aichi “Val” single-engine dive bombers, but two later turned back, reducing the number to 13. A strong force of Mitsubishi Zero fighters flew escort. An egregious error kept available American fighters over the Fletcher and Radford, leaving DeHaven unprotected.

The approaching planes were identified as enemy dive bombers about one minute after the initial sighting. All guns that could be brought to bear were training on them. The order to fire, however, was not immediately given.

The delay, presumably due to the commanding officers wanting to be sure the planes were indeed enemy, proved fatal. “When the planes reached a position about on the starboard quarter, six of them changed course sharply and came directly at the DeHaven,” Williams explained. He watched as the aircraft dove at about a 45-degree angle. The ship’s guns quickly opened fire after the belated order arrived but could not prevent the enemy planes from unleashing their bombs. One near miss damaged the hull, but three bombs squarely hit the destroyer in rapid succession.

Reporter Foster Hailey watched the attack unfold from his position aboard Nicholas. He momentarily focused on a single plane in a steep dive. “There was the flash of an explosion between DeHaven’s stacks, followed by a billowing cloud of black and brown smoke,” he wrote before his attention quickly switched to a plane approaching his ship.

The attack on DeHaven was over in a matter of minutes. The first bomb landed amidships on the port side. The second hit the forward stack, knocking it over. The final bomb struck the front part of the superstructure, causing a tremendous explosion that ripped apart the middle of the ship.

Clem Williams saw the third hit from his position on the fantail and recalled, “Immediately the ship was covered with a heavy yellow smoke and I’m led to believe that this bomb reached the forward magazines and caused them to explode. The bridge superstructure was demolished by this bomb, the director was thrown off its base, back into the area between the forward stack and the main deck, apparently right by the mast which was snapped off at this time.” Commander Tolman was among those instantly killed.

The damage was catastrophic. All power was immediately lost as DeHaven settled by the bow and was sinking within two minutes. No abandon ship order was given as most senior officers were either dead or dying, but the surviving sailors knew they had to leave the doomed vessel quickly.

Williams moved away from his gun as the smoke started to clear. It did not take long for him to understand how bad the situation was forward. “I looked up and saw the superstructure was mangled, and I saw very few people on deck,” he later recalled. The area near the stern appeared to be undamaged, but he too knew it was time to get off. “I took the liberty on the fantail to pass the word to abandon ship to that group of men in the absence of further authority.”

A rush of frantic activity followed. Chief Boatswain’s Mates Stephen Kowalski and John Laine led the effort to get two life nets over the side. Sailors immediately began to jump off the ship, with several wounded men assisted in getting over the side. Williams checked to make sure the torpedomen had set the depth charges on safe so as not to explode after the ship went down. “We didn’t want to repeat some of the previous disasters resulting from failure to do that,” he later said. He deemed it too risky to try to locate any confidential documents, which were probably already destroyed on the bridge.

Williams knew it was time to get off when he saw the vessel was “down by the bow by about 30 degrees. It was very difficult to get a footing on deck then and she was going down fast.” He took one last look around the immediate area for survivors on deck before jumping into the sea.

The sailors were in an ocean covered with thick fuel oil. Williams remembered, “Everybody that jumped in got a good mouthfull of that, and everybody was pretty badly scared.” It took only a short time for DeHaven to completely disappear beneath the waves. An underwater explosion was heard shortly afterward, but it was attributed to one of the ship’s boilers rather than a depth charge. The survivors, only some of whom had life vests, gathered as many men together as possible while staying afloat by whatever means possible. “They even used the ship’s life ring, which I understand is practically never used as a life preserver.”

The LCTs that had been firing at the attacking planes just minutes earlier immediately switched to rescue mode, combing the area for survivors. One of the small boats rescued Williams and a group of survivors in his immediate area. Its commanding officer stood out at the end of the lowered ramp pulling aboard as many survivors as could be found.

The boat crew used their limited medical supplies as best as they could to help the wounded. Williams remembered, “There was just enough morphine to go around to the people who really needed it.”

Nicholas soon arrived on the scene to take aboard all of the wounded survivors. The destroyer had been attacked by eight planes. Near misses caused minor damage, killing two crewmen and injuring seven others. The Japanese lost a total of eight planes in the attack, some victims of American fighters that arrived late on the scene.

Other ships arrived a short time later to help transport survivors back to Guadalcanal. “I reported to Captain Briscoe on the bridge of the Fletcher and gave him as much as I could say right off about what happened,” Williams later said. The sailors were soon back on dry land. “That was the first time we had any idea of the terrific loss which the ship had suffered.”

The DeHaven lost 167 sailors. Thirty-eight of the 146 survivors were wounded. Of the

14 officers aboard, 10 were listed as missing in the aftermath of the sinking and three were wounded. Clem Williams was the only unwounded officer to survive. He authored

a report of the sinking in keeping with Navy regulations.

The Japanese evacuation of Guadalcanal was successful. The fighting was over about a week later. The destroyer DeHaven was one of the last warships sunk in the bitter battle for the island.

John J. Domagalski is the author of three books on World War II. Into the Dark Water: The Story of Three Officers and PT-109 (Casemate, 2014), Sunk in Kula Gulf (Potomac Books, 2012), and Lost at Guadalcanal (McFarland, 2010). His articles have appeared in WWII History, Naval History, and WWII Quarterly magazines. He is a graduate of Northern Illinois University and lives near Chicago.

This isfasinating news of my father Bill kelly who was a sailor upon this ship !! Thank you !!

My husband is descendant of Edwin DeHaven family from King Of Prussia Pennsylvania who migrated to that area in 1698. I have two large photos of the ship

Hello,

Thanks for providing the history of these terrible losses. Ajacent to my grandparents graves in Mount Vernon Washington there is a gravestone with the inscription “The Pacific is Don’s resting place”. The gravestone states that he was lost on the USS DeHaven. I’m currently writing a song about the cemetart and I am looking for any information regarding Don Randals lost aboard the DeHaven. He was a MM 3rd class. Lewis Donald Randles. He may have been the uncle of a deceased friend also named Don Randles. Any help or directions to resources would be appreciated.

Thanks,

Jay Follman

Clear Lake WA.

(360) 661 2058

Mailing address

12656 East Lake Dr.

Sedro Woolley WA.

98284