by A.B. Feuer

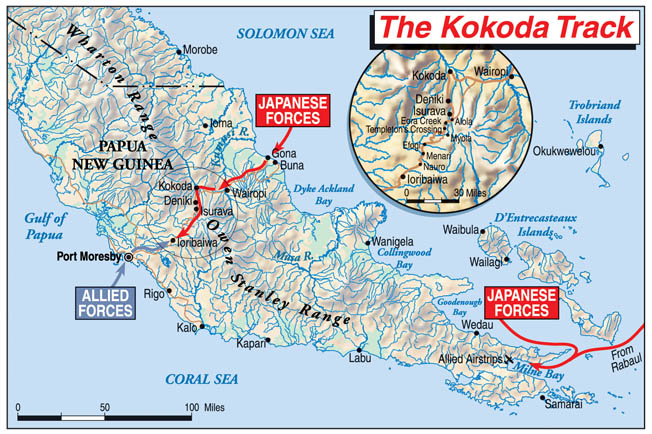

The Kokoda track campaign involved a trail that leada south along the western side of the Eora Creek Gorge and through the villages of Deniki and Isurava to a trail junction at Alola. From here the track rapidly climbs 6,000 feet to Templeton’s Crossing, then drops into deep valleys slick with deposits of humus and leaf mold.

The trail runs six miles over rocky ground, and through thick vegetation that chokes the narrow path between the sheer cliffs. The terrain varies only slightly as the track moves south. Although the gorges are deeper with thicker undergrowth, there are not as many to cross.

At higher elevations the land is covered with moss and stunted trees, while the valleys are interlaced with kunai grass and marshland. The swamps—reeking of pungent odors—teem with leeches and malarial mosquitoes. Not until about 30 miles north of Port Moresby does the track finally begin to moderate. Yet, it was by advancing over this tortuous trail that the Japanese would attempt a march from Buna to Port Moresby.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, Japan turned her attention to the conquest of the Philippine Islands and the Malay Barrier, a mountainous chain of islands stretching from Malaya across the Netherlands East Indies to New Guinea. (Read more about the events and battles in the South Pacific inside the pages of WWII History magazine.)

The Japanese advance was rapid. Troops stormed ashore, each with a bag of rice for rations and whatever ammunition they could carry. Singapore fell on February 15, 1942, and the bombing of Darwin, Australia, four days later awakened the Allies to the fact that Australia and New Zealand were virtually defenseless.

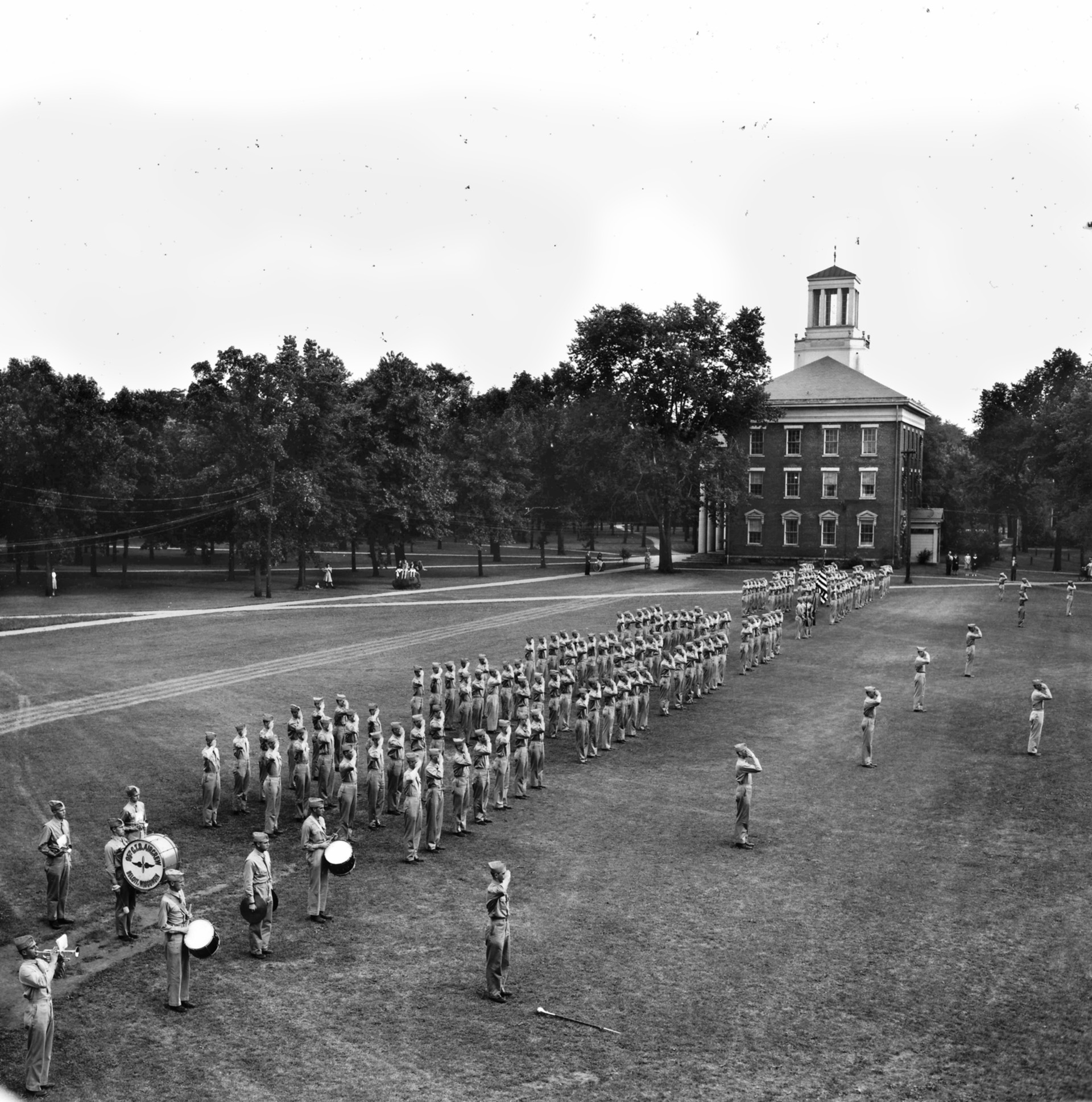

On March 7 Japanese transports landed 3,000 soldiers at Lae, New Guinea. Ten days later, General Douglas MacArthur arrived in Australia from the Philippines. MacArthur was quickly put in charge of a newly formed command—Southwest Pacific Area (SWPA)—consisting mainly of Australian and American regiments.

Australian General Sir Thomas A. Blamey was placed in command of the Allied Land Forces, which included the 21st Brigade of the 7th Division of the Australian Imperial Force, and part of the 6th Division that had just returned from fighting the Germans in the Middle East.

Japan Aims for Port Moresby

Meanwhile, the Japanese planned a three-pronged attack to capture Port Moresby. The first stage of the campaign was a landing at Buna and a forced march across the Owen Stanley Mountains. Next would be the capture of Milne Bay, followed by a drive west along the south coast of Papua and a naval assault on Port Moresby.

MacArthur conferred with Blamey, and they agreed that the enemy’s rapid advance was about to threaten the Australia/New Zealand supply lines—and the countries themselves.

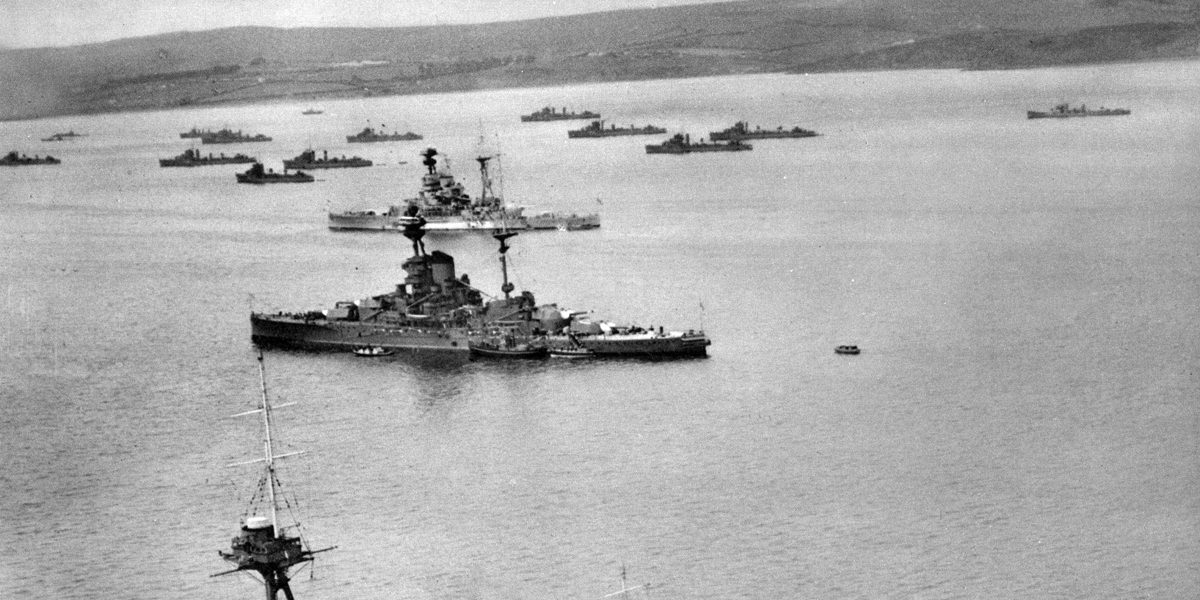

To the overly cautious Japanese, however, there were still too many unburned bridges. The British Far Eastern Fleet had to be neutralized; therefore, in April, a Japanese naval task force under Admiral Chuichi Nagumo steamed to the Indian Ocean to take on the English fleet. The battle was no contest. Nagumo’s superbly trained officers and men sank the British cruisers Dorsetshire and Cornwall, the carrier Hermes, a destroyer, a corvette, two tankers, and two transports.

Although Nagumo succeeded in crippling the English fleet, the delay gave MacArthur an extra month to reinforce the Port Moresby defenses.

On May 4 a Japanese invasion fleet sailed from Rabaul, New Britain, for the coast of New Guinea. As it approached the eastern end of the island on the morning of the 7th, the enemy task force was sighted by American carrier aircraft. In the ensuing Battle of the Coral Sea, the Japanese Navy was heavily battered and—although the U.S. Navy lost more ships—was forced to return to Rabaul.

Certain that the Japanese would attack again, MacArthur continued to secure the Port Moresby area. On May 14, the 32nd U.S. Infantry Division arrived in Australia, and the following day the 14th Australian Infantry Brigade began moving into Port Moresby.

One lesson learned by the Americans at the Coral Sea engagement was that, in order to effectively cover the eastern approaches to Port Moresby, the Air Force needed a base near the southeast tip of New Guinea. An airfield in this area would not only provide protection for Port Moresby, but also would give the Air Force a base for launching attacks against enemy positions to the north and northwest. A site suitable for more than one airfield was located at Milne Bay. A landing strip for pursuit planes was to be constructed immediately, and a bomber field at a later date.

On June 25, two companies and a machine-gun platoon of the 14th Australian Infantry landed at Milne Bay, followed by a company of the 46th U.S. Engineers. They quickly set to work building an airstrip. They were soon joined by the 7th Australian Infantry Brigade. Toward the end of July, the first Allied planes landed at the new airfield.

Japan Launches an Ambitious March on Port Moresby

Meanwhile, the Japanese decided to attack Port Moresby by advancing overland from Buna. This plan dictated a march through one of the most forbidding and unexplored terrains in the world.

On July 22 a landing force commanded by Maj. Gen. Tomitaro Horii, consisting of 2,000 troops, 1,300 laborers, and 52 horses, sneaked ashore at Gona. The enemy quickly moved about nine miles down the coast and seized Buna. Horii’s strategy was to cross the Papuan peninsula by way of Kokoda Village.

After securing their beachhead, the Japanese headed inland and, during the next two weeks, defeated several Australian and Papuan infantry units. By the middle of August they had reached the village of Kokoda. General Horii also received reinforcements, increasing his strength to 8,000 soldiers and 3,500 naval troops.

Phase 2 of Japan’s Attack Begins Badly

The Japanese then launched the second phase of their campaign to capture Port Moresby. On the night of August 24, MacArthur was notified by coast watcher L.G. Vail that seven enemy barges were moving east down the north coast of Papua.

The following day, New Britain coast watcher Ian Skinner reported that a convoy of nine Japanese ships had left Rabaul and was heading toward Milne Bay. Allied aircraft were quickly scrambled. They attacked the enemy flotilla, sinking one transport along with several of the barges creeping along the Papua shoreline.

Despite the air attack, the Japanese convoy still managed to land 2,000 troops on the north shore of the bay. Fortunately for the Allies, however, the Japanese soldiers were unloaded seven miles east of their intended beachhead.

The Japanese could scarcely have chosen a worse place to come ashore. They had landed on a jungle-covered coastal shelf, flanked on one side by steep mountains and the other by the sea. Because the cliffs were so near the shore, there was very little room to maneuver, and the heavy brush made it impossible to find a dry bivouac area.

It had been raining steadily for a few weeks, and the tropical storms continued. The unfamiliar terrain was marshy and treacherous as the Japanese carefully picked their way along the coast.

The Defense of Milne Bay Airstrip

The Allies’ first contact with the enemy occurred when an Australian launch sighted a Japanese barge unloading troops. The Aussies immediately came under heavy fire from the shore. Then, a short time later, east of what was known as the K.B. Mission, an Australian detachment stumbled upon the advancing enemy. Two small Japanese tanks were also seen lumbering down the narrow path along the edge of the bay. They had been fitted with spotlights, and the bright beams swept the jungle ahead of them. The spotlights were a new feature that enabled the Japanese to inflict heavy casualties on their enemy. The only antitank weapons the Australians had available were hand grenades—but most of them were wet and did not explode.

Bitter fighting lasted until dawn, when the Japanese withdrew into the jungle. The Australians still held the mission, and staged a counterattack, but they could not sustain the offensive. The enemy quickly resumed the attack—this time supported by tanks. The Australians retreated and prepared to defend the Milne Bay airstrips a few miles from Rabi. The runway was cleared, but only partially graded. A sea of mud along its eastern edge made a successful attack by tanks virtually impossible.

The Australian defenders had a broad field of fire, and the south end of the airstrip, less than 500 feet from the bay, was directly in the path of the advancing Japanese.

For the next three days, the Japanese tried unsuccessfully to breach the airstrip’s defenses. Two enemy tanks became bogged down in the marshy ground and had to be abandoned.

On the night of August 29, a Japanese flotilla safely unloaded 800 troops to reinforce their desperate forces. The following night, the enemy launched an all-out effort to take the strip. But, the Australians were ready for them. The Aussies set up .50-caliber machine guns at both ends of the landing field. Additional machine guns and 37mm antitank guns were positioned in the center of the line. Flanked on either side of the antitank crews were riflemen and mortar squads. Light artillery was stationed about a half-mile to the rear.

Wave after wave of Japanese rushed the airstrip, but to no avail. The heaviest Japanese attack came shortly before dawn, but it was also driven back. The enemy was forced to withdraw, leaving the bodies of several hundred men scattered near the airfield. The engineer company used a bulldozer to bury the large number of dead.

The Australians Counterattack

With the Japanese now in retreat, the Australians assumed the offensive, driving their enemy toward the sea. Just before daylight on September 3, a task force from Rabaul entered the bay to support their desperate troops. But, when Japanese Admiral Gunichi Mikawa learned that the soldiers were physically incapable of holding the beachhead, he concluded that the situation was hopeless and ordered Milne Bay abandoned.

About 1,300 Japanese troops were evacuated to Rabaul—nearly all of them suffering from malaria, jungle rot, tropical ulcers, and other diseases. Small bands of stragglers were all that remained of the enemy’s landing force, and they were soon wiped out.

The failure of the Japanese landing at Milne Bay cost the enemy at least 600 killed. The Australians also took a beating, with 123 killed and 198 wounded.

The Milne Bay battle was the first time—except for the initial attack on Wake Island—that a Japanese amphibious operation had been repelled. The effect on Australian troop morale was electric. The belief in the invincibility of the Japanese Army had been squelched.

Next: The Kokoda Track Campaign, and the Most Strenuous Battleground in the World

Pat Robinson, a war correspondent for the International News Service, wrote: “Although the Japs had received a severe setback at Milne Bay, this did not deter them from going ahead with their plans for a push down the Kokoda Trail. If they could not reach Port Moresby by sea, they would go over the mountains.

Pat Robinson, a war correspondent for the International News Service, wrote: “Although the Japs had received a severe setback at Milne Bay, this did not deter them from going ahead with their plans for a push down the Kokoda Trail. If they could not reach Port Moresby by sea, they would go over the mountains.

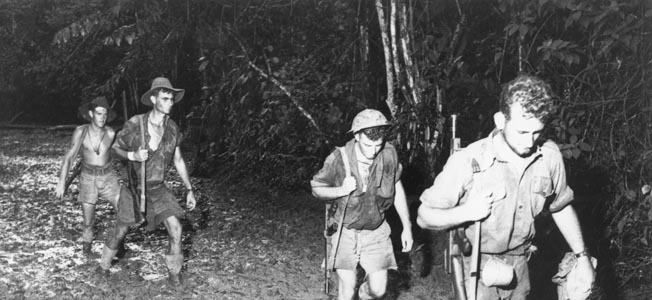

“The track from Kokoda, across the Owen Stanley Mountains, is probably the most strenuous battleground in the world. The Australian veterans who fought in the African desert and Europe said that fighting in those theaters was a holiday compared to what they had to battle in the jungles and swamps of New Guinea.

“The Owen Stanleys are so steep that soldiers could only climb the cliffs by clinging to trees and vines lining the precipitous narrow trails. A man could often be seen resting by straddling a stump or bush to keep from falling hundreds of feet. Even in dry weather, the ground is treacherous and slippery with decayed vegetation—and this was the rainy season.”

In addition to the jungle, mountains, and climate, the Australians also faced a cunning and determined foe. Robinson commented on the toughness of the enemy: “The Japanese soldiers lived off the land. They were never burdened with bulky supplies, but enslaved the natives in every village they seized, and forced the captives to carry packs and ammunition.

“The enemy soldier’s daily rations were only three cups of rice and vitamin tablets, but they supplemented this meager fare with fruit, yams and pigs that they stole from the native gardens.”

The Battle Begins

Meanwhile, General Horii readied his troops for the attack on Port Moresby. The Japanese force consisted of the 41st and 144th Infantry plus artillery and engineer battalions and miscellaneous units.

On August 26, Horii’s regiments marched out of Kokoda Village and headed for the Owen Stanley Range, the last natural obstacle between them and Port Moresby.

The Australians had only three battalions to oppose them. The Japanese were able to continually outflank the Aussies, bringing pressure to bear from different directions and forcing the defenders to retreat from one ridge to another.

Robinson remarked: “Jap snipers would shave their heads and paint their bodies green to blend in with the tropical background. The enemy soldiers were masters of jungle warfare. The snipers had hooks fastened on the inside of their boots—like telephone linesman—to facilitate climbing trees. They would sneak behind our lines—and remain motionless for hours—waiting for a chance to shoot one of our soldiers or toss a hand grenade. They also carried wicked knives—of razor sharpness—and several soldiers had small two-inch mortars strapped to a leg. Others handled flamethrowers that shot a jet of fire a hundred feet.

“The Japanese would call out orders in English, trying to trap the Aussies into revealing their positions. The enemy also took advantage of the night to slip unnoticed behind our lines. Our troops would then find themselves caught between two fires, and would have to battle their way out. The Australians simply did not have a force large enough to meet the Japanese at all points, and they could do nothing to prevent the enemy from encircling their positions.”

The Aussies—carrying heavy packs and cumbersome .303 rifles—were unable to gather their troops and make a stand to halt the Japanese advance. Not only were they outnumbered, but their rations and ammunition had to be carried over the mountains by native porters. Airdrops were also attempted, but both methods were inadequate. The Australians made a stand in late August at the high village of Isurava. The battle raged for three days. The more numerous Japanese worked through the jungles and hills around the flanks. Finally, the Australian defenses cracked. The Aussies pulled back across the crest of the Owen Stanleys to a defense line closer to their source of supplies, and waited for promised reinforcements.

General Horii was confident that his troops would soon be marching down the streets of Port Moresby. At Japanese Headquarters in Rabaul, however, the progress of the war was becoming a major concern. The capture of Milne Bay was in doubt, and the Imperial Navy was having trouble landing reinforcements on Guadalcanal. Headquarters also had another problem: Some of their best soldiers were dying during the Kokoda Track campaign.

Horii was directed to halt his regiments as soon as they reached the southern foothills of the Owen Stanley Mountains. He was also instructed not to resume the advance on Port Moresby until Milne Bay had been taken and the situation at Guadalcanal had improved.

The Japanese general chose Ioribaiwa to set up his line of defense. He had no sooner reached the village, however, when he received new orders emphasizing that all operations were to be subordinated to the desperate battle raging on Guadalcanal. Existing positions were to be held as long as possible. Moreover, the Japanese now had the same problem that the Australians had had on the northern side of the mountainous range: supply. The Japanese were at the very end of a very long, narrow, and steep trail, in parts accessible only to porters. In addition, Allied air power was striking at whatever supply efforts and bridges they could spot that the Japanese had assembled.

The Japanese general chose Ioribaiwa to set up his line of defense. He had no sooner reached the village, however, when he received new orders emphasizing that all operations were to be subordinated to the desperate battle raging on Guadalcanal. Existing positions were to be held as long as possible. Moreover, the Japanese now had the same problem that the Australians had had on the northern side of the mountainous range: supply. The Japanese were at the very end of a very long, narrow, and steep trail, in parts accessible only to porters. In addition, Allied air power was striking at whatever supply efforts and bridges they could spot that the Japanese had assembled.

Horii’s regiments were exhausted and soon his soldiers began to starve. Then he got more bad news. His most experienced unit, the South Seas Detachment, was ordered to return to Buna in case it was needed at Guadalcanal.

Japanese headquarters still hoped to be victorious in the Solomon Islands and Papua. As soon as Guadalcanal was retaken, they planned to divert those forces to New Guinea. Some regiments would seize Milne Bay and move up the coast to Port Moresby. Other troops would join the South Seas Detachment and head down the Kokoda Track to isolate the port.

MacArthur’s Lethal Three-Pronged Attack

The pause in the Japanese offensive gave the Allies time to reinforce their battle-weary troops on Papua. The Australian 25th Brigade was sent to Port Moresby and immediately rushed to the front.

MacArthur—taking advantage of the enemy’s weakened condition—planned a three-pronged attack to drive the Japanese out of the Papuan peninsula. The campaign would be accomplished by simultaneous advances over the Kokoda and Kapa Kapa Tracks by Australian and American forces. The main objective of this two-column offensive was to cut off and trap General Horii’s forces north of Kokoda Village at the Kumusi River.

A third column was to occupy and hold the north coast of Papua from Milne Bay to Wanigela on the east side of Cape Nelson. Upon securing the line of the Kumusi and the Cape Nelson area, all land forces would launch a coordinated assault on Buna.

In late September the 7th Australian Infantry Division headed up the Kokoda Track toward Ioribaiwa. Its orders were to drive the enemy back over the mountains, then cross the Kumusi River and occupy Wairopi Village.

Meanwhile, a battalion of the 126th U.S. Infantry Regiment set out from Port Moresby and moved east along the coast. It was to turn inland at Kapa Kapa and cross the Owen Stanley Range to Jaure.

About the same time, the 18th Australian and 128th U.S. Infantry were airlifted to Wanigela. Both groups had orders to sweep the coast of Cape Nelson to Embogo Village.

The Australians Rout the Enemy at Ioribaiwa

Pat Robinson described the 7th Australian Infantry’s attack at Ioribaiwa: “On September 28, the Australians stormed the Ioribaiwa Ridge. The assault was successful due in part to a bombardment by a couple of 25-pounders that had been hauled through the jungle and mountain foothills.

“The field guns blasted the wooden stockades protecting enemy machine guns and rifle pits. The Japanese were taken completely by surprise. They had believed it was impossible to bring artillery across such difficult terrain. General Horii’s troops were forced to abandon their positions. They fled so fast, in fact, that there were days when the Aussies did not see an enemy soldier.”

The Australian Army Staff Reports—Monograph #304—described the Japanese attempt to escape up the Kokoda Track: “It was difficult to catch up with the enemy as they fled north. They suffered from disease and shortage of food. A diary found on the body of a Japanese officer of the 144th Infantry stated that ‘some companies have resorted to eating human flesh.’

“Rations for the Australian troops were also limited, as they had to be hand-carried over the mountains. Airdrops were used, but damage and wastage was high.

“The Japanese retreated to well-prepared positions at Templeton’s Crossing. But the 25th Brigade scaled the cliffs and routed the enemy from one strongpoint after another.

“On October 20, the Australian 16th Brigade arrived at the front. They had been issued the new Owen gun, which gave the brigade a substantial increase in firepower.

Japan’s Last Stand

Meanwhile, a composite battalion of the Japanese 41st Infantry, reinforced with an artillery battery, set up a defense line on the heights below Kokoda. They had orders to hold their position as long as possible to cover the retreat of the 144th Infantry across the Kumusi River.

“The ensuing battle for the village was fierce—hand-to-hand—with heavy casualties on both sides. The bitter struggle was not decided until an Australian bayonet charge routed the enemy. The Aussies entered Kokoda Village on November 2. Mopping up operations followed, and continued for several weeks. General Horii drowned while attempting to cross the Kumusi.”

Thus the Japanese were defeated in their attempt to capture Port Moresby because they were distracted by the fighting on Guadalcanal. And because the Australians proved every bit as tough and skilled in the jungle and on the steep trails as their confident and hitherto victorious adversaries.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments