By Kevin M. O’Beirne

The city of New York provided more regiments than did many states during the Civil War, and the deeds of several of its regiments, such as the 9th New York “Hawkins’s Zouaves,” 39th New York “Garibaldi Guard,” and 42nd New York “Tammany Regiment” are well known. Perhaps the most famous New York City unit, the Irish Brigade, has eclipsed the deeds of another early-war regiment that was also mostly Irish—a regiment known officially as the 37th New York, and unofficially as “The Irish Rifles.”

The move to organize New York’s first Irish volunteer, as opposed to militia, regiment began less than two weeks after the fall of Fort Sumter. On April 21, 1861, the officers of the old, disbanded 75th New York State Militia gathered in Manhattan and adopted a resolution to reorganize the unit for service as a volunteer infantry regiment. Prominent New York citizens, headed by Judges Charles Daley, Lewis Woodruff, James Moncrief, and John McCunn, banded together to support the effort. The judges organized a finance committee and funds were raised to outfit and equip the new unit.

Within a week, six companies had enlisted and were drilling under their new officers. Eventually a seventh company was recruited in New York City, and the remaining companies were recruited in Pulaski (40 miles north of Syracuse) and the villages of Allegany and Ellicottville in Cattaraugus County in western New York State.

In late May, the regiment was redesignated the 37th New York State Volunteer Infantry and, on June 5, 1861, was mustered into Federal service. Between April and late June, the 37th continued to drill and train at its quarters in Manhattan, eventually achieving a state of discipline and military demeanor reportedly superior to most other volunteer units in the early months of the war.

Like many ethnic Irish regiments in the war, the Rifles carried a green flag of “the most costly silk” with various symbols of Erin, together with their national banner, the stars and stripes. The 37th’s flags were presented to the unit on June 21, 1861 and, the same day, the regiment also finally received Federal uniforms of indigo blue flannel.

Two days after receiving their flags, the 37th New York departed the state for the seat of war under the command of Judge John McCunn, who had been elected colonel. After an eventful trip marked by cheering throngs in various cities, and marching through secessionist Baltimore with bayonets fixed and weapons loaded, the Rifles arrived in camp in Washington DC around June 26.

The 37th participated in the First Bull Run campaign, although the regiment did not see front-line action. Throughout the balance of the summer and autumn of 1861, the Rifles remained in camp around Washington and participated in several raids and reconnaissances toward Bull Run.

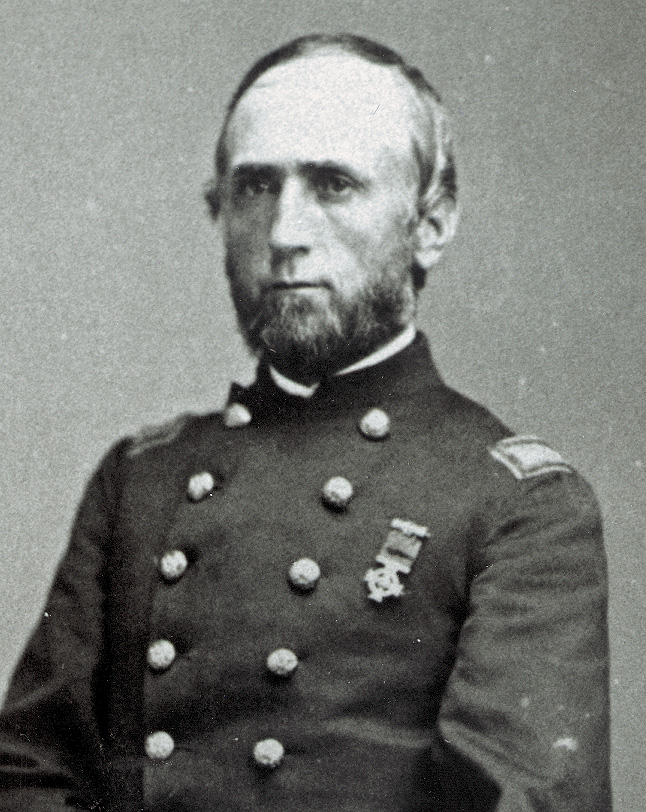

That autumn, the controversial John McCunn resigned as colonel and was replaced by a Regular Army officer, Colonel Samuel Hayman. Hayman was a veteran of the Mexican War and was an extremely capable career army officer who would serve as the colonel of the 37th for the balance of the regiment’s enlistment. The 37th was eventually assigned to Hiram Berry’s brigade, in the hard-fighting division of the one-armed General Phil Kearny, in Heintzelman’s III Corps of the Army of the Potomac.

The Rifles participated in the 1862 Peninsula Campaign, where they received a horrific baptism of fire. The regiment was in the thick of the fight at Williamsburg (May 5, 1862) where it lost 95 men in its first general engagement. The 37th was also heavily engaged at Fair Oaks (May 31-June 1), suffering 82 casualties; and at the battle of Glendale (June 30), losing 81 additional men. By the end of the Peninsula Campaign, the Rifles were true veterans and had established a reputation as a solid, hard-fighting regiment.

The 37th New York participated in the Second Bull Run campaign, particularly in the battle of Chantilly on September 1, 1862. The III Corps, together with the 37th, was held in reserve near Washington during the Antietam campaign and did not see action. The corps rejoined the Army of the Potomac that autumn and, on December 13, 1862, participated in the fierce fighting at Hamilton’s Crossing during the Fredericksburg campaign, where the 37th suffered 35 casualties. In the second half of January 1863, the regiment was part of Burnside’s “Mud March.” At least one soldier in the 37th’s brigade was not enamored with the Rifles one night during the Mud March after whiskey was issued to the troops:

“Matters assumed a very lively hue. Some of the New Yorkers [the 37th] air their eloquence at our expense, spoiling for a fight as the Irish always do when they have had an ‘odd sup.’ As their chance of getting at the Rebels is as small as their desire to do so, they exercised their pugnacity on each other. Judging from the howling, I’d say a good number of them have been converted into sausage meat. Noise is an Irishman’s special prerogative.”

New Flags Presented To Regiment By Grateful New Yorkers

After the Mud March the regiment went into winter quarters. Owing to the twin debacles of Fredericksburg and the Mud March the morale of the 37th and the rest of the Army of the Potomac was at its lowest point in the war. Many men in the 37th no doubt eagerly looked forward to the expiration of their enlistments; like many other New York State units recruited early in the war, the Rifles were a two-year regiment and were scheduled to be mustered out of the army in June 1863.

In mid-January 1863, in a public ceremony in New York, the 37th received two new flags from the grateful Common Council of New York City, because the original banners carried by the Rifles through the campaigns of 1861 and 1862 had been shot to ribbons and were no longer usable. The ceremony was attended by many dignitaries, including New York City politicians, and the flags were received on behalf of the 37th by Captain James O’Beirne, who commanded the regiment’s color company. O’Beirne was a well-known figure in New York City politics and responded with a patriotic speech before accepting the colors and returning to the regiment’s camp near Falmouth, Va. [Editor’s Note: Captain O’Beirne is not a direct ancestor of the author.]

After Fredericksburg and the Mud March, the Army of the Potomac’s commander, General Ambrose Burnside, was replaced by the competent although controversial Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Under Hooker’s command, the Army of the Potomac prepared for the coming spring 1863 campaign.

Similarly the winter of 1862-1863 brought organizational changes to the III Corps which affected the 37th New York. The corps was now under the command of Daniel Sickles, and the Rifles were assigned to David Birney’s 1st Division. The 37th’s colonel, Samuel Hayman, was promoted to command of the brigade, and Lt. Col. Gilbert Riordan and Major William DeLacy succeeded to command of the regiment. In late December 1862, the 37th received as reinforcements two consolidated companies from the old 101st New York, thus bringing the regiment’s effective strength to over four hundred men.

At Falmouth that winter, life in the camp of the Rifles was characterized by boredom. Like the rest of the Army of the Potomac, the men of the 37th New York benefited from Hooker’s improvement of the supply system, and morale improved when a limited system of furloughs was instituted and use of corps badges was prescribed. The corps badges increased men’s pride in their unit and, because they were part of the III Corps’s 1st Division, the badge worn by the 37th was the red lozenge (diamond). Under Hooker’s direction, the Army of the Potomac swelled to over 130,000 men organized into seven infantry corps, plus a new cavalry corps.

While winter quarters meant boredom for the enlisted men, Hooker’s headquarters was characterized by a flurry of activity as the commanding general, nicknamed “Fighting Joe” the year before by a newspaper reporter, busily plotted the destruction of Confederate General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia. Hooker had seen Federal generals George McClellan, John Pope, and Burnside all bested by the wily Lee, and he intended to return the favor in kind to the Rebels.

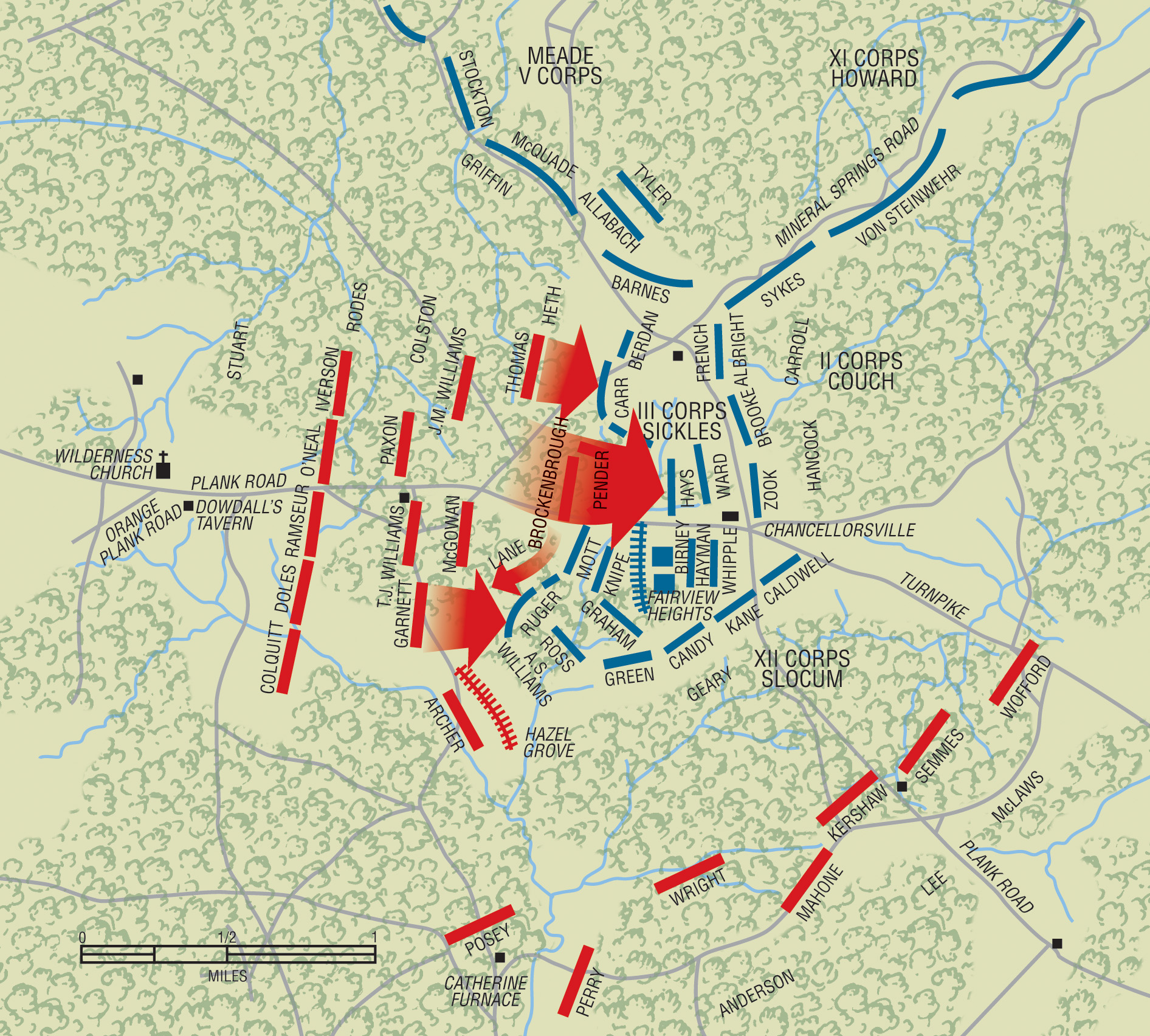

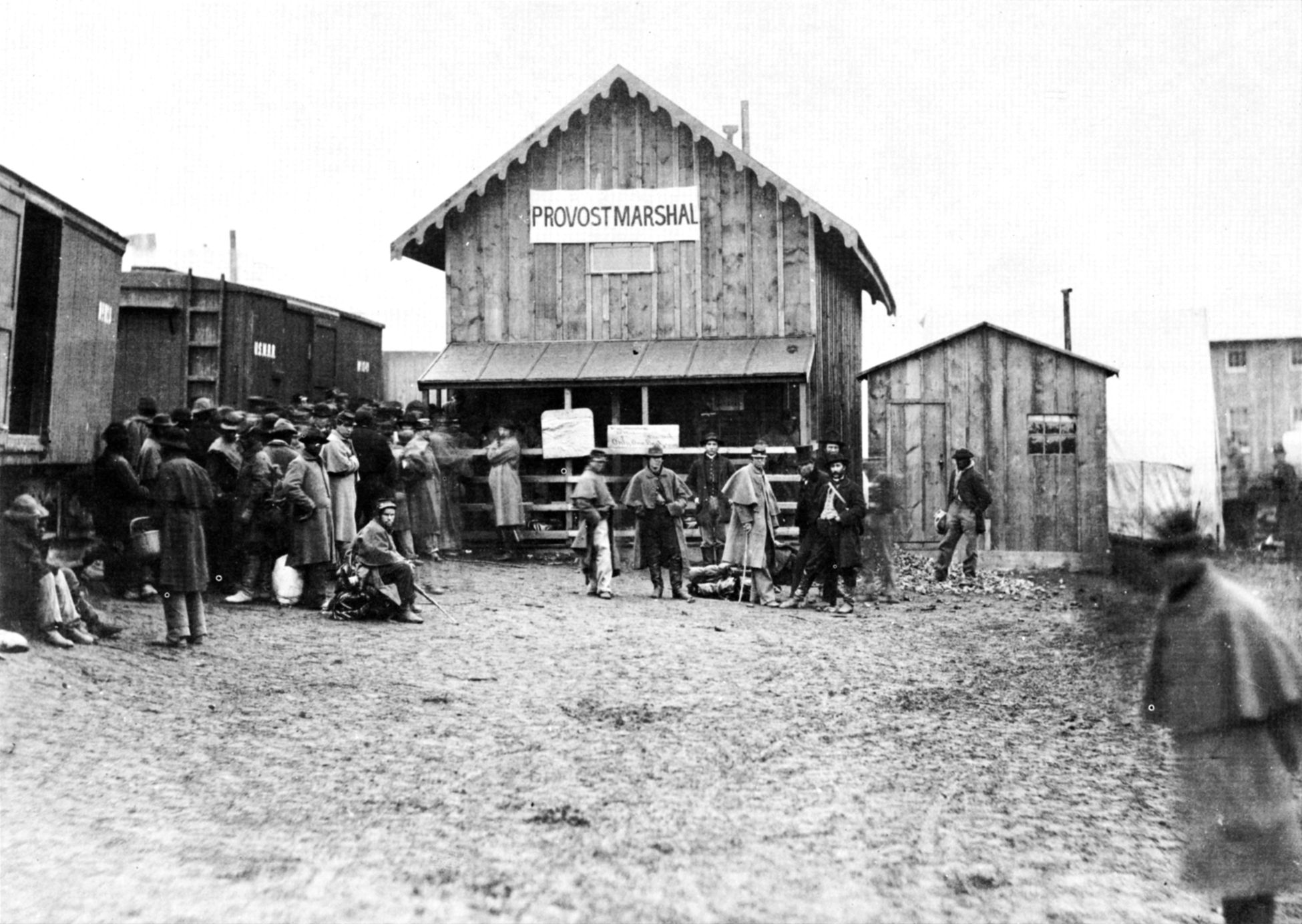

Hooker’s plan for what came to be known as the Chancellorsville campaign required swift marching and maneuver by large “flying columns” of infantry. The plan included a demonstration by the I, III, and VI Corps against the Confederates’ front at Fredericksburg. Simultaneously and in secret, the V, XI, and XII Corps were to march rapidly up the near bank of the Rappahannock River, cross it, march southward to and cross the nearby Rapidan River and, in a series of “lightning” marches, appear in Lee’s rear. The II Corps would march northwest along the Rappahannock behind the flanking column, occupy strategic fords over the river, shorten Hooker’s lines of communication between the wings of his army, and then cross to the river’s south bank. Eventually, the I and III Corps, the latter including the 37th New York, would march upriver and join the main army on the south side of the Rappahannock, while the VI Corps was to capture Fredericksburg and advance on Lee’s rear. The two wings of Hooker’s army would then hit the Confederate Army front and rear and destroy it.

On the morning of April 28, 1863, with the campaign already under way, the 37th New York and the III Corps struck tents and packed up. The men had some time to wait, and the column did not move out until 4:00 pm on April 29. The corps was camped a few miles north of Falmouth, and Hooker’s plan called for them to march south down the Rappahannock six miles to join the I and VI Corps in demonstrating against the Confederate positions four miles south of Fredericksburg.

In the morning of the 30th, Birney’s division, including the 37th New York, advanced to the Rappahannock crossings in the immediate rear of the VI Corps. At 2 pm that day, Birney, with the rest of the III Corps, received orders to proceed north up the Rappahannock to United States Ford, taking care to march by routes concealed from the view of Confederate pickets along the river. “After a tedious march of 10 hours with heavily laden knapsacks,” recalled a brigadier in Birney’s division, the column finally halted around midnight a few miles short of the ford. One officer in the 37th recalled, “Remarkable marches and countermarches continued throughout the day, and the night found us wondering just where we of the Third Corps were to be engaged.”

That night, “It was so cold our blankets froze to the ground,” shivered one of Hayman’s soldiers and, in the chill dawn of May 1, the march was resumed at 5:30 am. The tired New Yorkers trudged along in the early-morning light and reached the Rappahannock ford two hours later. The 37th crossed the river on a pontoon bridge soon afterward and marched toward a point on the map called Chancellorsville, where Hooker was concentrating the Army of the Potomac.

The Advance On Chancellorsville

Together with the rest of the III Corps, the 37th New York entered a tangled second-growth forest, known locally as the Wilderness of Spotsylvania. Spring rains made small rivulets difficult to cross and the men’s polished guns and clean uniforms were soon caked in red Virginia mud, but spirits were high. However, it is also likely that a bit of trepidation marked the thoughts of the Rifles because, when the campaign began, they were due to be mustered out in less than five weeks. By about midday, Hooker had concentrated the blueclad infantry at a large clearing in the Wilderness. The Orange Turnpike and United States Ford Road crossed in the center of the clearing, and the intersection was dominated by the only building in the area—the two-story Chancellor House, from which the crossroads derived its name, Chancellorsville. During May 1, elements of the V Corps pushed southeast from Chancellorsville along the Orange Turnpike and encountered resistance from Confederate units hurrying from Fredericksburg to stem the Yankee advance. The two sides skirmished for several hours, after which Hooker ordered the Federals to withdraw to Chancellorsville.

Apparently, “Fighting Joe” intended his army to take up defensive positions in the tangled thickets around Chancellorsville and await an assault by the Confederates. Hooker would later be sharply criticized for allowing the Rebels to seize the initiative in the campaign. To compound matters, “Fighting Joe” posted his newest and least reliable corps, XI, to guard the army’s vulnerable right (west) flank.

The 37th arrived at the Chancellor House plain at about 11 am, where the men stacked muskets and fell out to boil coffee. An hour and a half later, the bugle blew the call to attention and the men fell in and marched a mile and a half west out the Orange Turnpike. General Sickles rode along the column, cheering the men as he passed the 37th. One member of the Rifles remembered that, “occasional skirmishes, feeling for the enemy with sharpshooters and light batteries, broke the monotony of marching.” During the afternoon of May 1, the 37th was posted near Hooker’s right (west), while fighting continued on the Federals’ opposite (east) flank.

Late in the afternoon of May 1, the 37th was detached from Hayman’s brigade and served temporarily as part of General J. Hobart Ward’s brigade. The Rifles were ordered forward through the woods south of the turnpike to support a Federal battery posted on the high ground at Hazel Grove. After taking up a position at Hazel Grove, to the 37th’s rear was “an open space and in front was a meadow stretching out for a quarter of a mile to heavy woods beyond.” The Rifles stacked arms and commenced digging breastworks and throwing up abatis to their front. The men then “sat down to play cards, while others, more tired, lay down to smoke and rest,” remarked Captain O’Beirne.

The 37th New York and 20th Indiana sent pickets forward, resulting in a sharp evening firefight with Confederate skirmishers around a farmhouse south of Hazel Grove. The regiment remained at Hazel Grove until 7 am on May 2, when they were ordered back through the woods to the Turnpike to connect with the left (east) flank of the XI Corps.

Union Forces Stampeding Down The Turnpike

At midday, reports of Confederates at Catherine’s Furnace a couple of miles to the south—the rear guard of Stonewall Jackson’s column headed for Hooker’s exposed west flank—prompted Sickles to send two divisions to that place in the early afternoon. At 3:30 pm, Ward’s brigade moved out to the south to join the rest of Birney’s division. The 37th New York was apparently in the rear of Ward’s column and the Rifles did not advance all the way to Catherine’s Furnace.

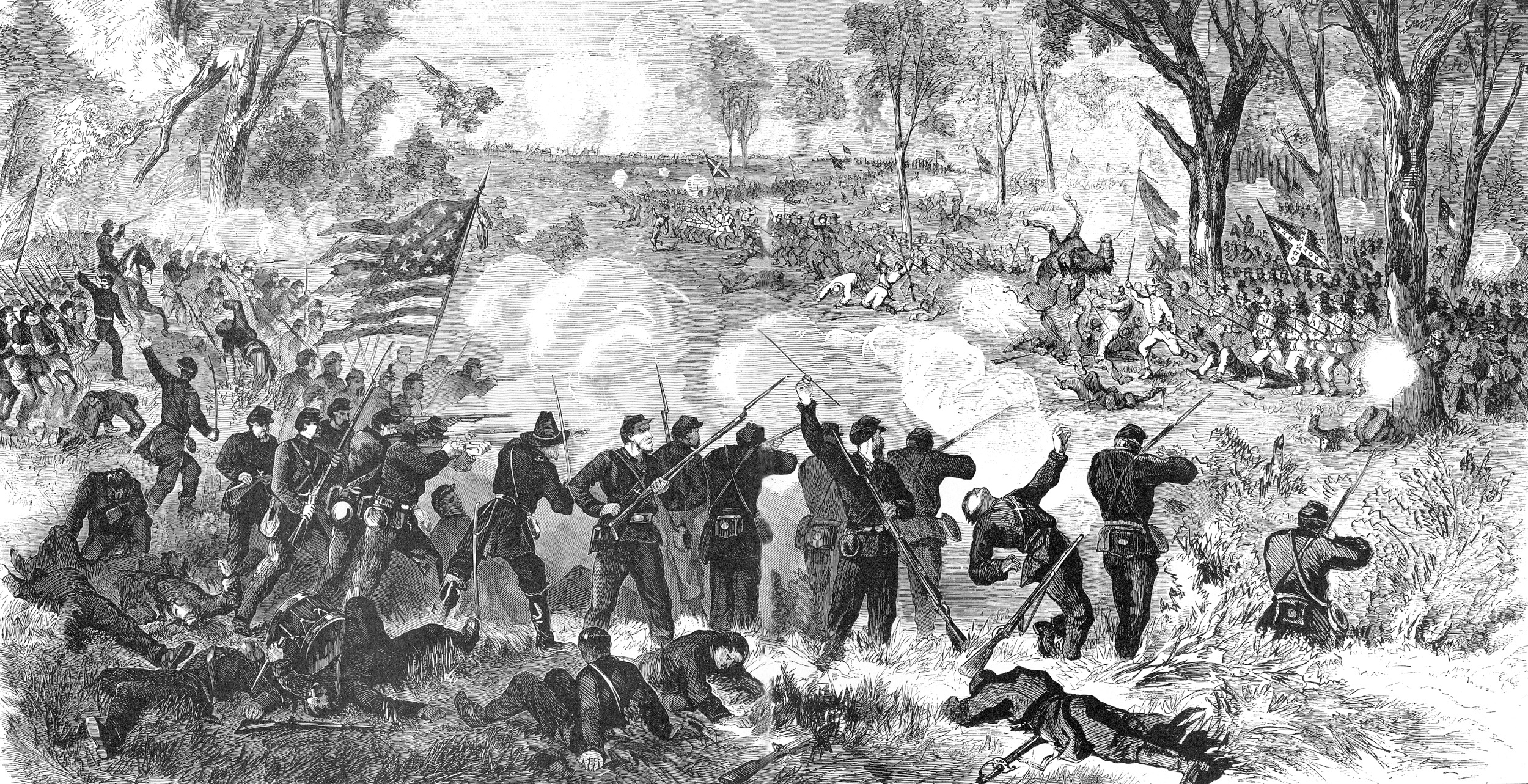

Between 5:45 and 6 pm on May 2, the New Yorkers heard sudden, heavy musketry off toward the XI Corps’s position, as Jackson’s attack broke on the Federal right flank. Much of the XI Corps, posted on the turnpike northwest of the 37th, stampeded back toward Chancellorsville, followed by the victorious Confederates. The Southerners’ battle line was centered on the turnpike and extended through the woods for at least a half-mile north and south of the road.

To the south, Doles’s Georgia brigade advanced through the Wilderness and eventually emerged into the giant clearing at Hazel Grove. Sickles had staged the III Corps’s advance to Catherine’s Furnace from this point and the near portion of the clearing was filled with the Sickles’s wagon train. As the Georgians emerged from the woods, the III Corps train stampeded. As described by historian Stephen Sears, “A great tangle of Third Corps wagons, ambulances, caissons, and runaway horses and mules rivaled the [XI Corps’s] scene on the Turnpike.” With the Confederates bearing down on them from the west and heavy firing to the north, the panicked teamsters fled east toward Chancellorsville and south into the tail end of Sickles’s brigades.

The 37th New York was one of the regiments closest to the chaos. Captain O’Beirne recalled that a stampede of men came rushing through the woods and down the road and passed through his ranks crying, “Stonewall Jackson is coming!” Lieutenant Colonel Riordan directed the 37th to form across the road with rifles held horizontally in an effort to halt the teamsters’ rout.

But one look at the Confederates swarming out of the Wilderness had convinced the teamsters that flight was the best alternative and they barged past the New Yorkers. As the Rifles were about to be swept along in the press of men, a wagon came along and the men of the 37th turned it perpendicular to the road to act as a barricade. This helped to stem the rout but, as Captain O’Beirne observed, “Some of the more active and terrified [fugitives] swarmed over the very canvas top of it, with the agility of acrobats.”

The fugitives soon found that they could go no farther owing to the jammed roadway and, as Sickles reported, “A few minutes was enough to restore comparative order.” Sickles and General Alfred Pleasonton brought up artillery, and double-shotted canisters from 22 guns soon sent Doles’s grayclad Georgians running for cover back into the woods.

Stonewall Jackson’s charge had routed the XI Corps and nearly cut off the III Corps from the rest of the Army of the Potomac. But rapid victory had disorganized the Rebels almost as much as the Unionists, and the momentum of Jackson’s charge could not be maintained. After order was restored on the 37th New York’s front and the regiment rejoined the rest of Hayman’s brigade, the brigade and the corps marched north and took up positions in and around Hazel Grove, facing north toward the turnpike.

As the Rifles advanced back toward Hazel Grove, they were amazed at the mess left by the panicked teamsters and the Federal artillery that had turned back the Confederate attack. Fifty years later, O’Beirne remembered that the twilight view that greeted the 37th upon its return to Hazel Grove as “a scene of slaughter not to be imagined from mere description. Everywhere [were the] maimed and dying.” He also recalled, “Guns and sabers were scattered here and there, amid haversacks, clothing, canteens, and side arms strewn broadcast.”

Sickles’s two divisions detailed to the expedition to Catherine’s Furnace—Birney’s and Whipple’s—were isolated from the rest of the Army of the Potomac, with Rebels to the front (north) and west and, to a lesser extent, to the south. Some distance of nearly impenetrable Wilderness separated Sickles from Slocum’s XII Corps to the northeast. On his own initiative, Sickles determined to make a nighttime bayonet charge northward, toward the Orange Turnpike a mile away, in an attempt to re-establish his connection to the rest of the army and recapture some of the earthworks lost by the XI Corps.

so much of the armies and their movements, is in the foreground.

“Rely Upon the Bayonet Alone”

Also to the north, so Sickles thought, were portions of III Corps’s wagon train still in Confederate hands, together with a few III Corps cannon; hopefully, a successful nighttime assault would recapture the lost vehicles and guns. By 10:00 pm, most of the firing around the turnpike and through the Wilderness fell off to only the scattered popping of skirmishers’ rifles as the exhausted men attempted to snatch an hour or two of rest. The next 12 hours would be the most active and bloody in the 37th New York’s history.

Between 10 and 11 pm, orders for Sickles’s bayonet charge arrived at the regiments. One man in Hayman’s brigade thought, “Something desperate was in the wind. The officers gathered in little groups and, after conversing for a few minutes, separated, shook hands, and expressed the hope that they ‘would come out alive.’” Hayman ordered the brigade to “take the caps from the rifles and rely upon the bayonet alone.” The success of the attack would require the element of surprise, and the men were ordered to move as silently as possible.

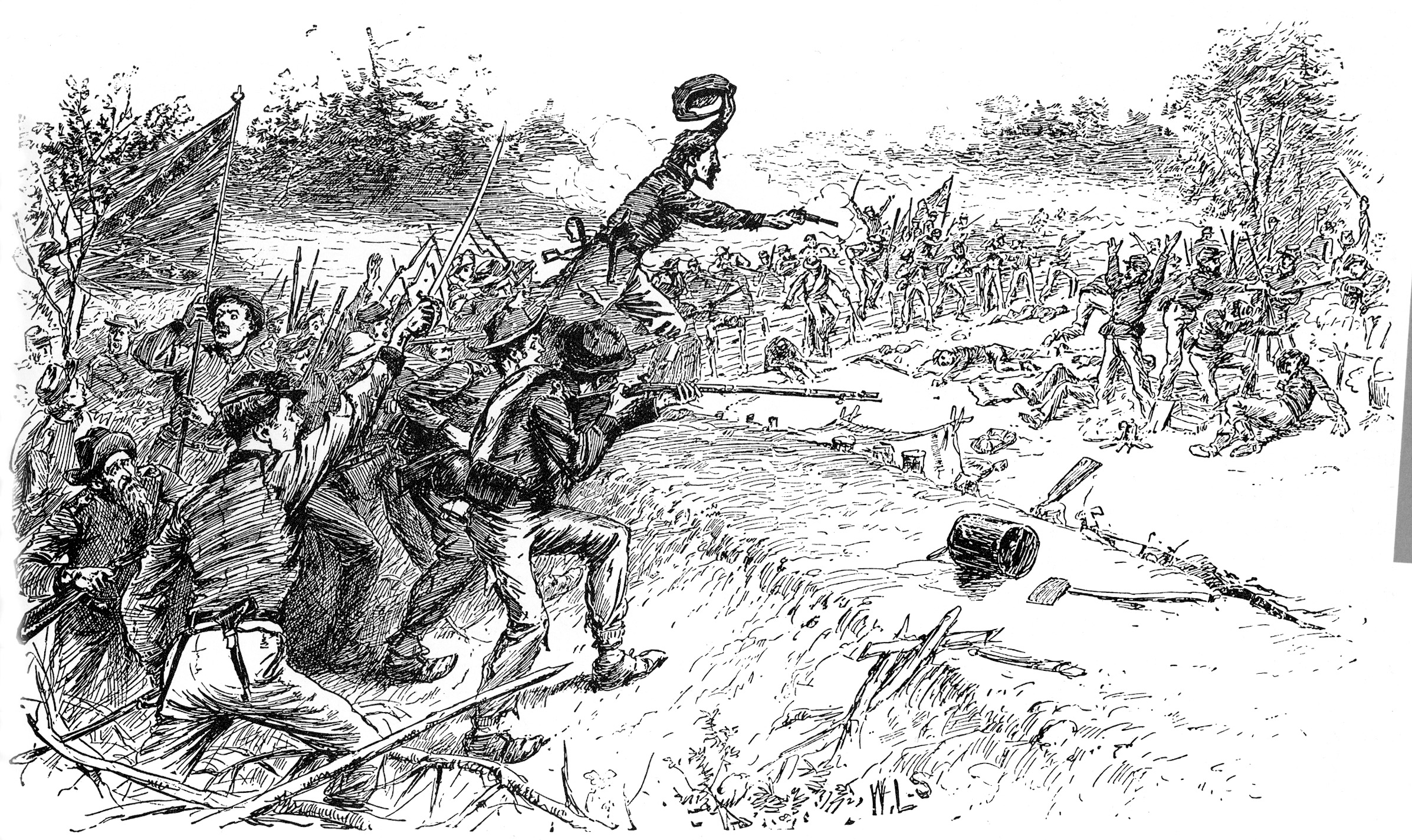

At about 11 pm the battalions were formed, with Ward’s brigade in the front, followed at a distance of a hundred yards by Hayman’s brigade with the 37th New York. Because the dense forest of the Wilderness prohibited movement in traditional battle lines, the advance was made by the right of companies to the front (i.e., parallel columns of men, four men abreast). Color sergeant Michael Lloyd of Company C, convinced that the bayonet charge would be suicidal, tore the 37th’s national colors from their staff and wrapped them around his body before the charge to prevent their capture.

The battalions were ordered forward at midnight. Officers led the parallel columns through the dense thickets with drawn swords and hushed, whispered orders. Extraordinary care was taken to keep quiet, as the Confederate earthworks were thought to be approximately five hundred yards from the Federal line. A full moon shone brightly and assisted the progress of the march. The 37th’s Captain O’Beirne recalled,

“Guardedly the long line[s] groped through the woods. Glimpses only of the midnight moon flitted through the tall and sentineled forest … and gave a silver, ghoul-like sheen to the battalions. … Occasionally a soldier stumbled and pitched forward. Up! Forward again! No detention, no hesitation! How could he halt? The rear rank and others were striding behind him at close distance.”

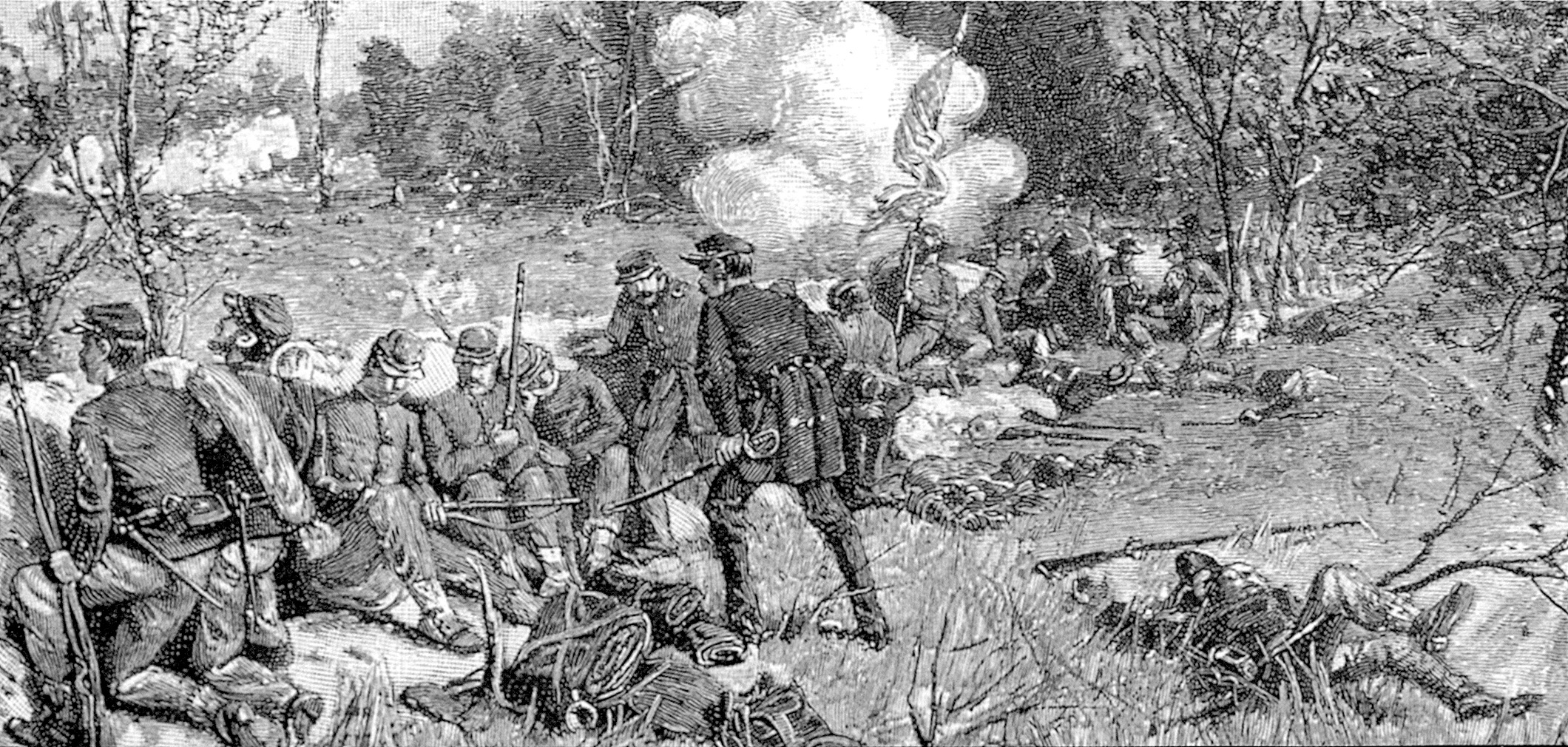

The Federals, not yet deployed into a battle line, got within a short distance of the Confederate earthworks when a shot rang out. Men of the 37th remembered that, instantly, the entire line of earthworks ahead was aflame with gunfire, “standing out in startling relief against the dark background of the night, the musketry discharge took on an outline of a lurid, quivering, undulating sheet of flame,” recalled one man in the 37th. A man in Hayman’s brigade penned in his diary, “The Rebel shots went over our heads instead of through them.” All order instantly evaporated in the Federal ranks as Hayman’s brigade charged forward and mixed with Ward’s leading brigade.

The Rifles broke into a run, as fast as was permitted by the dense woods and darkness, and reached the breastworks. O’Beirne recalled, “It seemed for the moment as if the doors of a blast-furnace had opened upon us.” Some of the New Yorkers crested the works and, according to one participant, put the bayonet “silently and effectively to work.”

It is likely that only a limited number of men in the 37th actually fought with the Confederates that night. Not only did Confederates bar Sickles’s path, but the left (south) flank of most of the XII Corps was also to the III Corps’s front and right. Elements of the III Corps collided with the XII Corps, resulting in casualties from “friendly fire.” Colonel Hayman reported, “The rifle pits were carried in the face of a terrible fire from both friend and foe; at least such is the opinion of the officers and enlisted men of my command.”

All order was lost in the melee. A Maine man in Hayman’s brigade remembered the chaos: “Such a panic ensued as I cannot describe—officers begging, threatening, and swearing, but all to no purpose. Discipline was a dead letter. Men were as sheep huddled together, each intent on saving his own precious head.”

Captain O’Beirne ran along with his men until he was struck on the left side of his forehead by a ricocheted bullet. He staggered and fell to the ground, clutching a tree stump. Dazed from the blow, he groped at his forehead in the darkness and, years later, remembered, “I was seized with a spasm of delight, mingled with resentment, to discover that I had not received a wound.” He struggled to his feet and followed his men through the woods.

The charge had driven some of the Rebels, as well as portions of the XII Corps, from their earthworks but, as the 37th’s Major DeLacy later reported, “[We] were received so warmly, and not knowing the amount of damage done [to] the enemy, it was deemed prudent to fall back.” Together with the rest of Birney’s division, the 37th slowly sorted itself out and eventually returned to the area of Hazel Grove.

Thus the effort and terror and bloodshed of the charge had accomplished little except to confirm to Sickles that there were Confederates as well as Union units to his north. Still feeling his corps was isolated, Sickles received permission to withdraw from Hazel Grove at first light.

During the midnight fighting, Color Sergeant Lloyd was killed. His body was recovered and buried by his buddies, none of whom knew that the national flag was wrapped around Lloyd’s torso directly under his jacket. The location of his grave was not marked and thus the 37th New York lost its new national colors.

J.E.B. Stuart And The 37th On Collision Course

The morrow would portend severe fighting, as the Rebels attempted to connect the two halves of their army. The 37th went into bivouac, stacked arms, and tried to grab a few hours of fitful rest in the dew-covered grass of Hazel Grove.

Years later, Captain O’Beirne recalled a chilling story. Attempting to gain a couple of hours of rest, O’Beirne found a soldier already rolled in a blanket and, carefully lifting up a corner of the wool, he crawled under and went to sleep. By 4 am, his company was awake and boiling coffee over small fires, and the Federal pickets were being recalled. At the campfire, O’Beirne looked back and saw a solitary sleeper still rolled in his blanket—the same man with whom he had slept. He ordered a lieutenant to awaken the man; the lieutenant returned in a moment and reported that the man was not asleep, but dead.

Meanwhile Sickles had ordered his two divisions at Hazel Grove to withdraw east toward Chancellorsville at first light. Accordingly, a little after 5 am, Hayman began forming his brigade and the march to the rear commenced. At about the same time, the southern portion of Jackson’s Corps, now commanded by Maj. Gen. Jeb Stuart owing to the friendly-fire wounding of Jackson the night before, simultaneously moved forward to forcibly eject Sickles from Hazel Grove. Samuel McGowan’s veteran South Carolina brigade crept through the Wilderness on a collision course with the 37th.

A member of Hayman’s brigade, in line near the 37th, wrote of the Confederate assault, “A yell greeted our ears and the Rebels swarmed from the woods at the very spot where we had slept. They waltzed out as gaily and confidently as though we were their legitimate property.”

The 37th New York was the last regiment in Birney’s column, and it was not formed into a battle line when the South Carolinians fell on it. Taken by surprise, Lt. Col. Riordan desperately ordered the regiment, “On the right, by file into line, march!” Major DeLacy wrote, “Before half the regiment was formed, the enemy opened a deadly fire on our front and left flank.” Riordan remembered, “I engaged the enemy, who came out of the woods on every side, in great force, as fast as I could form the companies.” He went on, “A most terrific fire in front and on our flanks was poured into us, killing and wounding many men and officers.”

Captain O’Beirne reported that “the tree-tops [were] alive with [Confederate] sharpshooters,” who proved to be experts at picking off Union officers. Order in the 37th began to disintegrate. While standing with the green flag and attempting to rally the color company, O’Beirne was shot though the chest, puncturing his lung. He sagged to the ground, bleeding profusely, with his right arm paralyzed from shock. His second lieutenant rushed to his side and helped the stricken officer to safety as masses of grayclad troops charged at them.

DeLacy admitted that McGowan’s fire,“caused a little confusion on the consequence of the regiment not being formed, which compelled us to fall back.” The 37th lost dozens of men killed and wounded, and retreated in disorder. McGowan’s exuberant South Carolinians, tasting the first victory of the day, charged and took almost a hundred men of the 37th New York prisoner in the ensuing confusion.

Riordan’s horse became “unmanageable” and he left Major DeLacy to rally the regiment and supervise its retreat. Riordan maintained that “the regiment continued fighting and retiring to the rear.” The rest of the III Corps, in somewhat better order than the 37th New York, conducted a fighting retreat back toward Chancellorsville.

Aided by his second lieutenant, O’Beirne staggered about a mile through the woods to the Chancellor House, which served as army headquarters, a hospital, a rallying point and, by this time, as the main battlefield. A small creek ran through the large Chancellorsville clearing and the wounded O’Beirne was laid within its banks, to be out of the way of the artillery fire that occasionally cut across the area. Colonel Hayman rode up, spoke quickly with O’Beirne, and then rode off to see to the rest of the brigade.

In a few minutes, Meagher’s Irish Brigade marched by on its way into battle. An acquaintance from New York City, Captain John Lynch of the 63rd New York, stepped out of line as they passed to “say a tender good-bye” to O’Beirne. As he trotted away to catch up to his regiment, from a few yards away, O’Beirne witnessed Lynch’s head taken off by a cannonball.

A group of men from O’Beirne’s company was directed to carry him away from Chancellorsville on a makeshift stretcher of muskets and a rolled blanket. One man refused to join the detail, and he was immediately hit in the torso by a Rebel cannonball. As the soldier’s body was scattered in all directions, O’Beirne recalled one of his bearers sarcastically remarking, “Oh boys! Look at the rawhide!”

In the confusion of the retreat toward Chancellorsville, Riordan assumed that Hayman’s brigade had been ordered to the rear. Arriving at the Chancellor House, he came upon Major DeLacy, who had rallied 50 or 60 men of the regiment. “I rallied my men as best I could,” Riordan lamely reported. Riordan heard rumors that Birney’s division was ordered rearward to United States Ford.

He observed portions of Hayman’s other regiments moving in that direction which convinced him that the rumor was true, and he led the fragment of the 37th three miles farther to the rear. Hayman later censured Riordan for the unauthorized withdrawal, “for which, in my opinion” he wrote, “there can be no satisfactory excuse.” Hayman’s sentiment was echoed by General Birney, who opined, “The conduct of Lieutenant-Colonel Riordan, Thirty-seventh New York in taking parts of [his] command to the rear, is as yet unexplained, and is certainly unsatisfactory.”

Riordan finally collected about a hundred of his men—probably more than half of the regiment’s unhurt survivors. Finding out that Hayman was still at the front with the balance of the brigade, he eventually marched the regiment back to Chancellorsville and rejoined the brigade on the front line.

Final Campaign Of the Irish Rifles Ends

Meanwhile, the balance of the 37th had remained with Hayman’s brigade and saw hard fighting throughout the morning of May 3. Severely diminished, the brigade was posted in support of a battery at Chancellorsville. It was here that the 37th New York made its final charge of the war, as reported by Colonel Hayman: “A small force of the enemy made a dash across the plain, which my brigade, led in person by General Birney, charged, and captured some 20 prisoners, including several officers. This charge broke my formation, and the brigade was not fully reorganized until it was placed in a strong position farther to the rear, although a portion of it still supported a battery near the brick house [the Chancellor House].”

By this time, probably about 9 am, the III Corps was out of ammunition and was ordered to withdraw. Hayman, together with Riordan and DeLacy, led the remnant of the battered 37th New York a couple of miles to the rear where Federal engineers had laid out a new defensive position.

The 37th New York remained in the new line from late in the morning of May 3 until after midnight on May 5-6, where they were subjected to sharpshooter fire and were occasionally shelled by artillery, but without seeing significant fighting. A member of Hayman’s brigade wrote of May 6, “We awoke this morning to find a first-class Virginia rainstorm in full blast, and ourselves as wet and wretched as it could make us.” Deeming the campaign a failure, Hooker had ordered the Union Army to retreat back across the Rappahannock. At 4 am, Hayman’s brigade was formed and started slogging its way through the deep mud, rain, and darkness toward the pontoon bridge at United States Ford. The retreat was completed without incident and the 37th arrived back at its old camp later that day. The last campaign of the Irish Rifles was over.

What of Captain O’Beirne? He was treated at the V Corps field hospital and, two days after being wounded, was evacuated back across the Rappahannock River. O’Beirne was dosed with morphine and was weak from loss of blood, and his stretcher bearers, some thinking that he was done for, discussed what to do with the nearly unconscious captain. One old, hard-bitten Crimean War veteran from O’Beirne’s company listened to it all and then opined that there was no way the captain would die. When the others asked why, he spat, “Arrah! Did ye hear that rousing big oath he let out of him when we knocked him agin the stump? If he was going to die, do ye think he’d swear that way?”

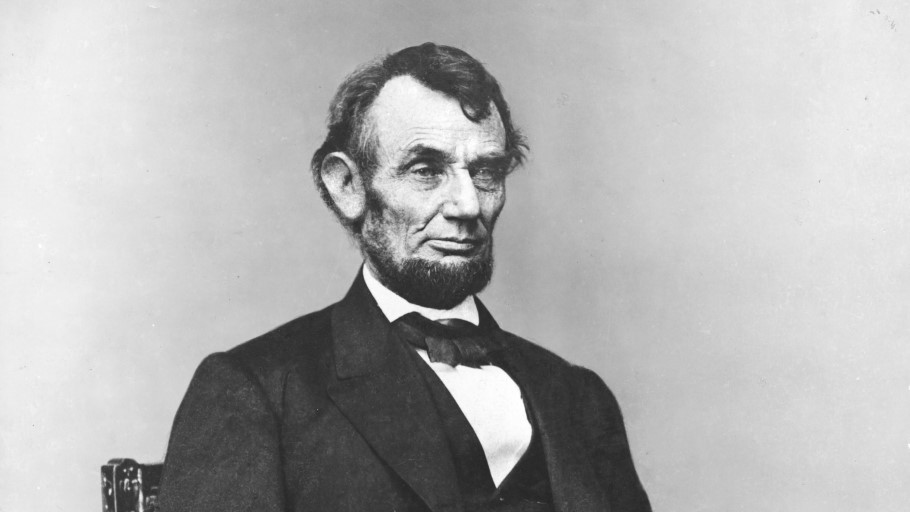

O’Beirne survived the Chancellorsville campaign and eventually recovered and enlisted in the Veteran Reserve Corps, seeing more action before the close of the war. During the battle of Fort Stevens in July 1864, he stood under fire with President Lincoln on the ramparts as Jubal Early’s Confederate troops were driven back from the gates of Washington, DC. Together with a detachment of Illinois cavalrymen, he pursued John Mosby through Northern Virginia, and in April 1865 helped lead the successful manhunt for Lincoln’s assassin, John Wilkes Booth. Arguably the most colorful officer in the 37th New York, O’Beirne was mustered out of the army in 1866 as a brevet brigadier general and had a distinguished postwar career. He received the Medal of Honor for actions at Fair Oaks in 1862, and passed away in 1917.

The 37th New York had been decimated in its final battle, going in with approximately 400 effectives and losing 222 men, including 115 killed and wounded and 107 missing, together with the regiment’s national flag. General Birney and Colonel Hayman commended the regiment for its performance under fire in their reports of the Chancellorsville campaign.

The survivors of the 37th remained at Falmouth until June 3, when the regiment, together with the 38th New York, broke camp for the return trip to New York City. The three-year men of the 37th and the old 101st New York were transferred to the 40th New York Regiment and saw severe action at Gettysburg. The other surviving Rifles were mustered out of the army on June 22, 1863. During their two years of service, the regiment suffered 530 battle casualties; an additional 38 died of disease and other causes.

Both Colonel Hayman and Major DeLacy were eventually brevetted to brigadier general for their service during the war. Remaining in the Regular Army, Hayman faded from history after the 37th was mustered out. DeLacy joined a brigade known as “Corcoran’s Irish Legion” and eventually became colonel of the 164th New York Zouaves, in which unit he served until the summer of 1865.

Between June and October of 1863, unsuccessful attempts were made to reorganize the regiment as the 37th New York Veteran Volunteer Infantry. The men who re-enlisted were transferred and served the balance of the war as Zouaves in the 5th New York Veteran Volunteers.

As the 37th departed the Army of the Potomac for the last time, General Sickles said of the Rifles: “The departure of [this] regiment recalls their distinguished record in the Army. Their conduct always elicited the emphatic commendation of the lamented Kearny…. In more recent campaigns, Major General Birney … has found occasions to signalize their rapid and orderly marches, their ardor and steadiness in action, and their admirable discipline in camp…. Wherever valor and fidelity are passports to honor and hospitality, [this] regiment … will be heartily welcome.”

General Sickles was an amateur political general. A column led by 4 men with bayonets would never work. The Rebel Army would move in a skirmish line through these same woods. I am sure it was total chaos that night.