By Michael Fellows

Lieutenant Commander John Benjamin Fellows, the skipper of the American Gleaves-class destroyer USS Gwin (DD-433), stood on the bridge trying to see into the predawn blackness. Forward of the bow, all he could see were the phosphorescent wakes of the convoy in front of his ship.

It was shortly after midnight on July 13, 1943, and despite the cover of night, it was still hot in the central Solomon Islands, some 650 miles south of the equator. The humidity was cloying; only the ship’s movement through the night air brought any sort of cooling relief to the crew on deck. The crewmen below, especially those in the “black gang” who were tending to the engines where the temperatures soared above 100 degrees Fahrenheit, glistened with sweat.

No one realized that for many of them and for their ship, it would be their last day on earth. But we’re getting ahead of ourselves.

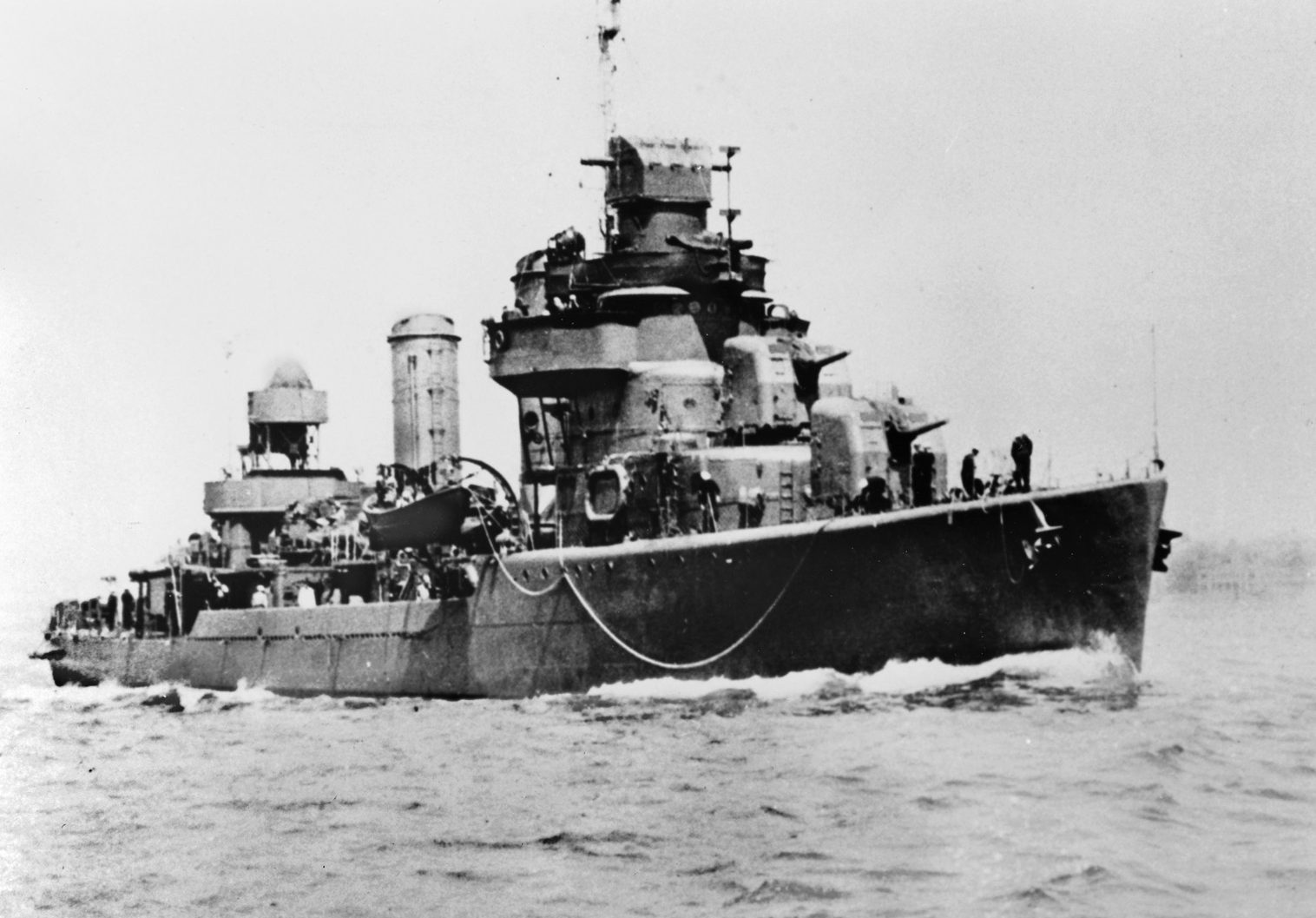

Gwin was named for Lt. Cmdr. William Gwin, a Civil War naval officer, and it was the third ship to carry that name. She had been built at the Charlestown Navy Yard at Boston and was commissioned in January 1941. And she was well-armed. Gwin had five Mark 12 5-inch dual-purpose guns, five 40mm twin antiaircraft guns, and 10 21-inch torpedo tubes. She had a range of 6,500 nautical miles and a top speed of over 37 knots.

Like all members of the Gleaves class, Gwin was 348 feet long, 36 feet at the beam, and displaced 1,630 tons standard. She had already served for 15 months on sea duty in the Pacific. On this day she carried a crew of 11 officers and 201 enlisted ranks—about the size of an infantry rifle company.

John Fellows was a seasoned and competent commander. Born in Fitchburg, Massachusetts (about 45 miles northwest of Boston), on February 16, 1910, he had graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1931—a full 10 years before the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor—and had previously served on such ships as the cruisers USS Chester (CA-27) and Chicago (CA-29) before transferring to the destroyers USS Talbot (DD-114), Warden (DD-352), and Crowningshield (DD-134).

In October 1940, Fellows became the engineering officer of the Gwin and was soon promoted to executive officer and then commanding officer. When war broke out, Gwin had been patrolling the waters around Iceland with the Atlantic Squadron, then was transferred to the Pacific.

There, the ship participated in one of the most storied actions thus far in the war—accompanying the aircraft carrier USS Hornet on its fateful mission to launch the Doolittle Raiders on their air raid against Tokyo on April 18, 1942. But she had not yet heard or fired a shot in anger. That moment was soon to come.

On May 23, 1942, Fellows and Gwin departed Pearl Harbor with a Marine Commando unit aboard to strengthen the Midway Island defenses. She then hurried to join the Fast Carrier Task Force that was racing to intercept a powerful Japanese fleet bearing down on Midway, but did not arrive until the battle was almost over.

Arriving during the final stages of the battle on June 5, Gwin’s officers and men learned of the American victory: four Japanese carriers had been sunk and about 250 enemy planes had been splashed. But the American carrier USS Yorktown (CV-5) had been heavily damaged by torpedoes and aerial bombs and was in danger of sinking.

Gwin came alongside the Yorktown to do whatever she could to save the carrier and her crew, but the flattop was torpedoed again on June 6; another rescue ship, the destroyer USS Hammann (DD-412), was also helping in the salvage and firefighting efforts when, at about 3:36 pm, a Japanese torpedo slammed into the Hammann in the vicinity of the No. 2 gun and exploded, breaking the ship’s back. The command to abandon ship was given, and most of the surviving crew went over the side. Three minutes later, Hammann was gone.

Risking their lives, Gwin’s salvage party continued to try to save the Yorktown but she began listing badly, forcing Gwin’s men to abandon their efforts. They nonetheless managed to pull 102 survivors out of the water. Gwin then returned to Pearl Harbor on June 10, 1942.

A month later, on July 15, 1942, Gwin departed Pearl and set course for Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands chain. The 1st Marine Division was scheduled to invade Guadalcanal on August 7 and would need all the help it could get to establish a beachhead and move inland. The Navy was to supply that help.

The Solomons were strategically vital for both sides. If the Japanese could defeat the Americans there, Japan would prevent the United States from building up the amount of men and supplies in Australia necessary for MacArthur to move north and recapture lost territory, especially the Philippines. Cut off from aid, Australia itself would also be strangled to death.

Conversely, the Japanese realized that if they lost the Solomons, there would be little to stop the Americans from reclaiming hundreds of islands while driving closer and closer to Japan. It was, therefore, a matter of utmost urgency that the Japanese do everything in their power to prevent an American victory—just as the Americans were committed to doing everything possible to ensure that they would be victorious. Thus, the fight for the Solomons became, after Midway, the most important contest in the Pacific Theater up to that point of the war.

On August 7, 1942, 19,000 Marines came ashore on Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the Florida Islands. The landings were intended to establish a base from which the Americans could disrupt Japanese attacks on the supply route from the United States to Australia. During the fighting, the Marines captured a Japanese airfield at Lunga Point on Guadalcanal that they renamed Henderson Field. The Japanese, whose main base was at Rabaul, 650 miles to the northwest, were determined to retake the lost real estate.

To reinforce and resupply their troops scattered throughout the Solomons, the Japanese ran warships and transport ships under cover of darkness down “the Slot”—a narrow channel between Choiseul and Santa Isabel Islands to the north and Guadalcanal and San Cristobal Island to the south. The Slot became the watery superhighway through which supplies and men from Rabaul and other bases could be funneled to their starving, beleaguered garrisons fighting on Guadalcanal and Tulagi. The Americans called these nightly enemy supply runs the “Tokyo Express.”

Savo Sound (aka the Slot) was a shipping lane so dangerous that it had acquired another nickname: Ironbottom Sound, for all the sunken warships that covered its floor.

To put an end to the Tokyo Express, the Americans established cruiser-destroyer Task Force 67.4, led by Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, with his flag on the light cruiser San Francisco (CA-38).

Callaghan was one of the Navy’s finest officers. He had been naval aide to President Franklin D. Roosevelt and was chief of staff to Admiral William “Bull” Halsey, Jr., commander of the South Pacific Area, before requesting sea duty. The request would cost him his life.

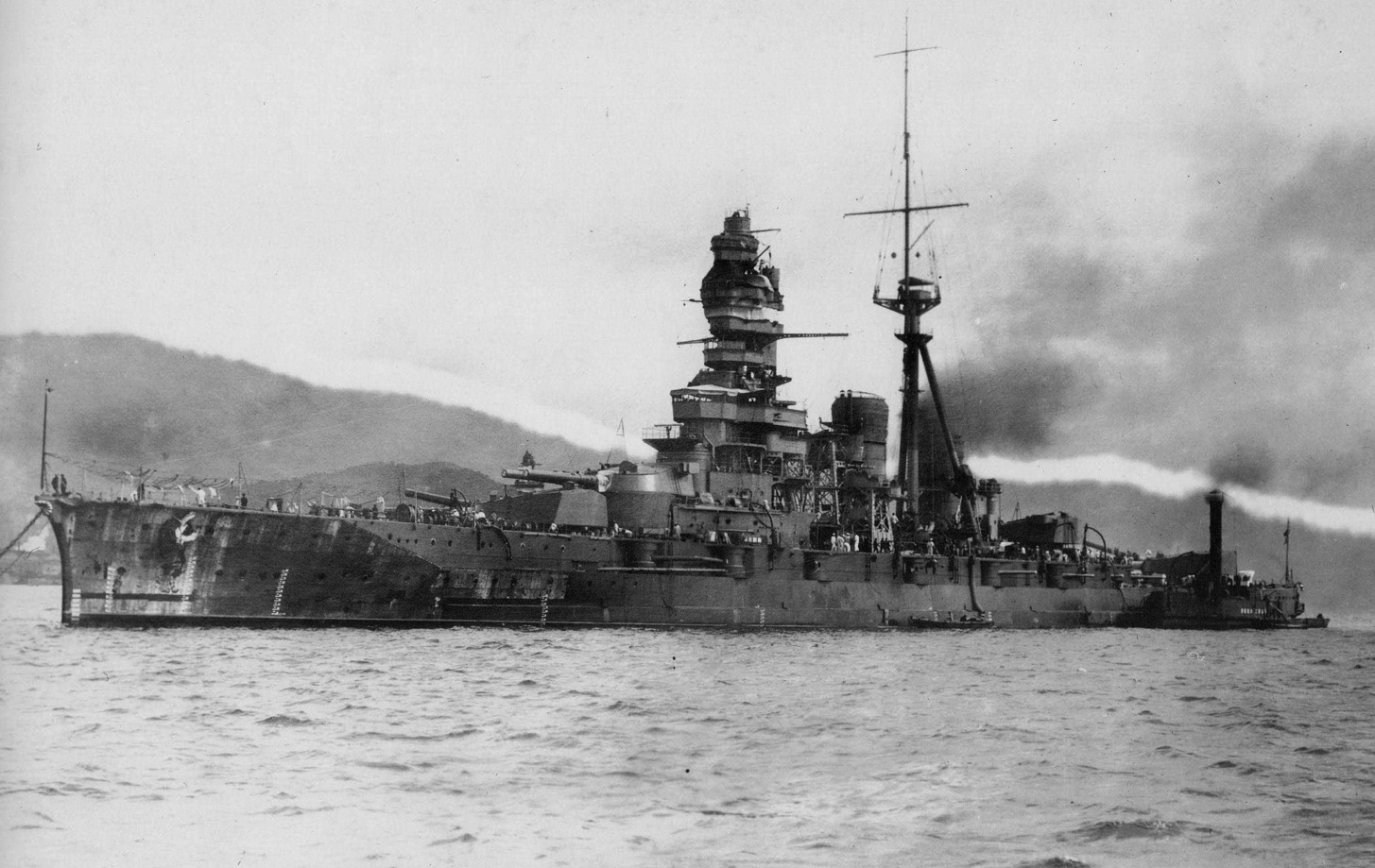

Aboard his flagship Yamato, anchored at Truk Lagoon, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto directed Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe to bombard Henderson Field on Guadalcanal so that a 12,000-man followup landing force under Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo could come ashore to reinforce the garrison there without the danger of American aerial attack. To accomplish this mission, Abe was put in command of a formidable naval assault force of two battleships (Hiei and Kirishima), a light cruiser, and 14 destroyers.

Before the ships arrived, however, the Japanese decided to make a hit-and-run aerial attack. Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner, in command of Task Group 67.1, was himself in the process of reinforcing and resupplying the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal which, after more than three months of fighting not only the fanatical Japanese but also insects, disease, torrential rains, heat, humidity, festering wounds, and malnutrition, was about at the end of its endurance.

Turner’s transports were finishing the process of dropping off fresh men and supplies at Lunga Point when they were suddenly attacked on the afternoon of November 12 by 32 Rabaul-based torpedo bombers and aircraft from the carrier Hiyo, which stood off to the northwest. Turner pulled his transports away from the beach, had all the antiaircraft guns manned, and arranged his ships in a defensive formation that would leave them less vulnerable to aerial attack.

Enemy planes dropped their bombs and torpedoes but caused little damage. U.S. Marine aircraft from Henderson Field then rose up like aerial knights to joust in a deadly tournament in the sky.

The gunners on the American vessels also took their toll of the Japanese, and 31 warplanes were knocked out of the sky. The pilot of a disabled “Betty” bomber chose the San Francisco on which to make his suicide dive, killing or wounding 50 sailors and causing tremendous damage—but failing to knock out the ship.

Later that afternoon, Turner’s transports returned to finish offloading, but few believed the Japanese were gone for good. Nervous lookouts scanned the sky and sea, searching for any sign of the enemy’s return.

Intelligence soon reported that the Imperial Japanese Navy was indeed on its way. Halsey received word—thanks again to the top-secret “Magic” code breakers, who acted like spies in the other team’s huddle—that Abe’s flotilla was steaming toward Guadalcanal, and he passed the information on to Turner.

Halsey also called upon his single operational aircraft carrier—Rear Admiral Thomas Kincaid’s Enterprise (CV-6), which was then undergoing repairs at Noumea—to head for Guadalcanal as soon as possible.

Turner ordered the offloading halted and the transports diverted to take shelter at Espiritu Santo. Waiting for the Japanese to return was Rear Admiral Callaghan’s Task Group 67.4.

In Callaghan’s command were two heavy cruisers (Portland [CA-33] and damaged San Francisco), three light cruisers (Atlanta [CL-51], Juneau [CL-52], and Helena [CL-50]), and 15 destroyers. Callaghan then arrayed his ships across the 20-mile-wide strait between Guadalcanal and Florida Island—the infamous Ironbottom Sound—to await the Japanese convoy.

Unaware that the Americans were setting an ambush, Abe’s task force came streaming down the Slot past Savo Island at about 1 am on November 13. Forty-five minutes later, although visibility in the dark was zero, the radar operators aboard the cruiser Helena detected two groups of unknown ships dead ahead. The First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was about to begin.

Night was turned into day as the range closed and the gunners opened fire. Caught by surprise, Japanese vessels switched on their searchlights in an effort to find targets—an act that turned themselves into targets.

At 10 minutes before 2 am, a Japanese searchlight illuminated the cruiser Atlanta, serving as flagship for Rear Admiral Norman Scott, commander of Task Group 64.2. Atlanta fired in the direction of the light with her 5-inch guns, extinguishing it, but the muzzle flashes caused Japanese destroyers to zero in on the cruiser, and she was struck and physically lifted out of the water by a torpedo fired point blank from the destroyer Akatsuki.

Akatsuki was itself sunk when it was smothered by return fire from Callaghan’s flagship, the San Francisco. To make matters worse, in all the confusion, Atlanta’s bridge was then mistakenly blown apart by a salvo of shells from San Francisco, whose gunners were trying to hit an enemy ship on the other side of her. Admiral Scott and all but one of his staff were killed and Atlanta was left dead in the water. The cruiser would be scuttled later that night.

For the next half hour, munitions ripped back and forth across the darkened strait, the shells punching holes in hulls and bulkheads, crashing into bridges and gun mounts, sending hot shards of steel flying and ships to their doom. Men from both navies were blown into the water or jumped willingly into the shark-infested sea, their bodies aflame. Few if any naval engagements have ever been so intense or so destructive in such a short period of time.

The two sides resembled blindfolded boxers standing toe to toe and flailing away at each other. The waters of the strait were soon coated with fuel oil, floating debris, and the mangled, intermingled corpses of Japanese and American sailors. The dark morning continued to be brightened by flashes from scores of guns and the bursts of orange-colored balls of flame from shells that found their marks.

The burning San Francisco came under a torrent of fire from the battleship Kirishima, and 77 of her crew, including Admiral Callaghan and Pearl Harbor Medal of Honor recipient Captain Cassin Young, were killed.

Despite the deaths of Callaghan and Young, the badly damaged San Francisco remained in the fight, sinking a destroyer and crippling the Japanese battleship Hiei (which was later sunk by a B-17 flying out of Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides).

Aboard San Francisco, Lt. Cmdr. Herbert E. Schonland and Lt. Cmdr. Bruce McCandless kept the cruiser fighting after Callaghan’s death, while Boatswain’s Mate First Class Reinhardt J. Keppler fought fires and treated the ship’s wounded in the heat of the battle. All would be awarded the Medal of Honor, Keppler’s posthumously.

During the slugfest, Portland, Helena, and Juneau were badly damaged, the latter sunk the next day by enemy submarine I-26 along with her captain, Lyman K. Swensen, and nearly 700 sailors, including all five Sullivan brothers—Albert, Francis, George, Joseph, and Madison.

An especially heavy toll was also exacted on the American destroyer force. Barton (DD-599), Cushing (DD-376), Monssen (DD-798), and Laffey (DD-459) were lost, while Sterrett (DD-407), Aaron Ward (DD-483), and O’Bannon (DD-450) were seriously damaged. Buchanan (DD-484) was mistakenly blasted by friendly ships but remained afloat.

Evidently losing his nerve in the wild melee in the dark, Admiral Abe was unaware of his good fortune and ordered his big ships to break off contact and retreat to the north while his smaller ships screened the withdrawal. Yamamoto was so furious with Abe for what he deemed a cowardly act that he replaced him with Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo.

What has also been called the “Cruiser Night Action” was finally over, but the fight for Guadalcanal was not.

As the Japanese ships hauled out of range, the American sailors concentrated on dousing the fires that had broken out and tending to their wounded. With Admirals Callaghan and Scott dead (both would be awarded the Medal of Honor, posthumously), Captain Gilbert C. Hoover of the Helena found himself the highest ranking officer still alive and took command of what was left of Task Group 67.4.

However, Halsey reprimanded Hoover for abandoning the Juneau survivors and relieved him of command.

Admiral Halsey was informed by Navy intelligence, whose cryptanalysts were still intercepting and deciphering Imperial Japanese Navy messages, that the enemy had not given up its attempts to knock out Henderson Field and come to the aid of the Japanese garrison on Guadalcanal, and were already sending another force south. Just like Abe’s flotilla the previous night, this force outnumbered anything the U.S. Navy could assemble.

Ordered by Yamamoto to knock out Henderson Field and reinforce the troops on Guadalcanal, Vice Admiral Kondo headed into action aboard the battleship Kirishima accompanied by five heavy cruisers (Maya, Atago, Suzuya, Takao, and Kinugasa), two light cruisers (Isuzu and Nagara), and as many as 11 destroyers and 23 troop transports.

But Halsey had very little with which to derail Kondo’s Tokyo Express. Most of his cruisers were either already committed to battle elsewhere or heavily damaged, and his fleet of destroyers had been badly depleted.

With Callaghan’s task force decimated, the only truly effective power that Halsey had left in the area to stop the Japanese was Task Force 64, commanded by Rear Admiral Willis Augustus “Ching Chong” Lee, Jr., and consisting of the battleships USS Washington (BB-56) and South Dakota (BB-57), and four destroyers—Gwin, Walke (DD-416), Benham (DD-397), and Preston (DD-379). All would soon be involved in the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal.

Operating out of the naval base at Espiritu Santo, John Fellows’ Gwin was one of many ships that had been tasked with bringing supplies and reinforcements to the Marines fighting on Guadalcanal and Tulagi, as well as providing antiaircraft and gunnery support for the Marines ashore.

On the night of Friday, November 13, 1942, Lee’s task group ran into Kondo’s force. As the American fleet initially stumbled blindly in the dark, a series of communication failures and command blunders allowed the Japanese to gain the upper hand, and the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (also known as the “Battleship Night Action”) was on. It was just as fierce as the one that preceded it—a battle that has been called “the most furious surface action of the entire war,” and what one sailor described as “a barroom brawl after the lights have been shot out.”

Two of the Japanese cruisers, Maya and Suzuya, got close enough to shell Henderson Field with nearly 1,000 rounds that destroyed two fighters and two dive bombers and damaged 17 other planes.

Assisting Lee’s ships were aircraft from Enterprise, 300 miles away, and from Henderson Field, which gave the enemy a good going-over. Near Cape Esperance north of Savo Island, aerial torpedoes struck Hiei four times, followed by a 500-pound bomb from an Espirito Santo-based B-17. Mortally wounded, Hiei was a sitting duck for another group of aerial attackers. Japanese destroyers took remaining crew off by that night, and it later sank five miles off Savo Island.

The Americans fought back hard. In the predawn of November 14, a flotilla of PT boats from Tulagi arrived on the scene and, after firing their torpedoes, scared off the Japanese bombardment force.

At 8:30 am, a dozen Japanese transports were spotted in the Slot heading for Guadalcanal. Additionally, search aircraft from Enterprise spotted the bombardment group that had retired to the northwest around New Georgia and radioed the sighting to the carrier, which immediately dispatched another swarm of attack planes.

At 10:14 am, warplanes bombed the cruiser Kinugasa, causing it to list and flood. An hour later, more planes arrived and began strafing and bombing Chokai, Maya, and Suzuya, forcing them to flee.

A group of Henderson-based B-17s then took to the sky and dropped bombs around the troop transports but failed to hit them. The Dauntless torpedo bombers were a different story as they managed to sink six and caused the others to retire in haste.

When the final tally was made, the Japanese had lost one battleship (Hiei), one cruiser (Kinugasa), 17 aircraft, and eight transports either sunk or dead in the water. The Americans had lost five planes, four officers, and two enlisted men.

But the Japanese were not easily dissuaded. They would return later that night.

At 13 minutes past midnight on November 15, Lt. Cmdr. John Fellows reported that the destroyers Walke, Benham, Preston, and his Gwin were in a column leading the battleships that were about 5,000 yard astern: “South Dakota reported contact, bearing 330, range 16,300 [yards]. Gwin observed two cruisers, believed to be Mogami type, bearing 355, range about 14,000.”

Six minutes later, South Dakota opened fire. The other ships also began firing, with Gwin ordered to send up “two star-shell spreads to illuminate [enemy] cruisers under fire of [U.S.] battleships…. Fired two salvos AA [antiaircraft] at cruisers, but range was too great for the gunfire to serve other than distraction purposes.

“Opened fire on right-hand ship of what appeared to be one cruiser and four destroyers, which were apparently in column and circling Savo Island in a counter-clockwise direction.”

At 27 minutes past midnight, Fellows entered into the ship’s log, “One of the two cruisers on our starboard quarter is now flaming, and the other apparently retiring to the northwest. Walke burning and has pulled out of column to port. Benham and Preston are still firing at targets which appear to be [destroyers]. Targets are very difficult to distinguish as they are masked by Savo Island.”

Three minutes later, Fellows noted, “We hit [the Ayanami] with two consecutive salvos. Target which had been firing 4-gun salvos now is replying with one gun…. We are being fired upon by a Kumo-type cruiser on our port quarter…. Preston exploded dead ahead, distance 300 yards. Almost simultaneously, ship [the Gwin] received 4.7 caliber hit which entered forward starboard side of #2 engine room.”

The shell exploded in the vicinity of the control station, killing six men on the upper level, filling the engine room with steam, and driving the crew out of the gun mount 4 handling room. “General lighting is out in guns 4 and 5 but they still have power and battle lighting.”

Fellows also noted that safety links securing the deck-mounted torpedoes had failed and some of the “tin fish” had fallen overboard.

Although smoke billowed from her wounds, and her torn-up decks were awash in bodies and blood, Gwin stayed in the fight despite flooding in her forward compartments. Then Fellows had to make a hard turn to keep from hitting the burning Preston and felt his ship nearly lifted out of the water. Fellows wrote, “[Preston’s] depth charges exploded right after we had passed her and gave the ship quite a shaking up.”

Gwin then received a hit that put a jagged, two-foot hole on her starboard side and caused two 600-pound depth charges on deck to split open. Luckily, they did not explode.

At 34 minutes after midnight, November 15, Fellows reported that his “ship is still firing at flashes in the lee of Savo Island, using guns one, two, and five. One of the [U.S.] battleships has destroyed the cruiser firing on our port quarter. Torpedo crossed astern, coming from starboard, missing stern by about 30 yards. Benham has disappeared from formation.”

Kondo believed, without confirmation, that the American force had been defeated, so shortly before 1 am he sailed off temporarily to the northwest to allow his bombardment force to come closer and plaster Henderson Field. Suddenly, Japanese lookouts discovered the presence of both Washington and South Dakota.

The Japanese opened fire and launched torpedoes in the direction of the American dreadnoughts, which replied with their main guns. Kondo’s flagship Kirishima was hit by nine 16-inch and 40 5-inch shells and put out of action. She soon capsized and slipped beneath the waves, carrying almost 200 sailors to their watery grave. Kondo was saved and taken aboard another ship.

At dawn on the 15th came a cessation of the battle, with both sides having suffered greatly. Dead and burning ships floated on the sea along with numerous bloated bodies. Washington, unscratched, and South Dakota, battered and bruised, headed back to Noumea.

The battle resembled Nelson against the French and Spanish at Trafalgar in 1805, except that sail and wood were replaced by steam and steel. In the free-swinging brawl against the superior enemy force, two American destroyers (Preston and Walke) were sunk and Benham had much of her bow blown off. Gwin, although severely damaged and with only one operational engine, was the only destroyer to survive more or less intact. She began rescuing men from Benham.

Gwin, at a reduced speed of five knots, tried towing the disabled Benham back to Espiritu Santo but the two slow-moving ships presented an attractive target, and so Benham had to be abandoned, her crew transferred, and then scuttled.

Lieutenant Commander Fellows reported that at 5:45 pm his ship “fired on Benham with main battery. Numerous fires were kindled before one salvo caused a tremendous explosion, which apparently broke the ship in two abaft the stack. Explosion appeared to be torpedo warheads. Ship sank with bow and stern rising up and touching as she went down amidships.”

Like two bloodied, battered, and exhausted boxers, the battle’s survivors limped back to their ports. During the two Naval Battles of Guadalcanal, the U.S. had lost the cruiser San Francisco and seven destroyers. Admiral Callaghan was dead. South Dakota had been damaged.

The Japanese had lost two battleships (Hiei and Kirishima), one heavy cruiser, two destroyers, 11 transports, and 64 aircraft. The Americans had lost a total of 1,732 sailors and airmen killed. The number of Japanese sailors lost was at least 1,900, with an estimated 20,000 soldiers killed aboard the transports.

With Fellows’ ship hors de combat, it was off to Noumea, New Caldonia, for repairs. But his ship was too badly damaged for repairs to be effected locally, so Fellows and Gwin left Nouméa and struck a 5,300-nautical mile course for the shipyards at Mare Island, near San Francisco, for an extensive overhaul. While ashore, Fellows received the Navy Cross, the Navy’s second highest award for valor, for his calm and cool command of his ship during the chaotic night battle.

Another Gwin sailor, Machinist’s Mate 1st Class Earle C. Johnson of Manchester, New Hampshire, also received the Navy Cross for his actions on November 15, but it was a posthumous award because he died of his wounds.

Despite the losses, the Americans managed to prevent the Japanese from retaking Guadalcanal or putting Henderson Field out of action. In retrospect, the Naval Battles of Guadalcanal were one of the major turning points of the Pacific War.

But the fight was not yet over for Gwin.

Early in March 1943, with repairs and sea trials having been successfully completed, and with new crewmen reporting on board to replace those who had been killed or injured, Gwin left Mare Island and joined a Pearl Harbor-bound convoy, arriving there on March 28. Fellows’ ship was then assigned escort duties, which led her back to the Solomons and eventually to Tulagi Island on June 4, 1943.

On June 21, Gwin sailed back into harm’s way, this time with Task Unit 32.8.3 en route to the Western Solomons and Rendova Island, dubbed the “Malta of the Pacific,” 200 miles northwest of Guadalcanal. Three days later she arrived at Lunga Point to begin antisubmarine patrols, which included the Japanese-held northern side of New Georgia Island, which resembles a fat comma.

On June 29, Gwin and eight other destroyers were assigned to screen Task Unit 31.1.3, consisting of various transports destined for assault landings on Rendova Island. This was to be the first step in Operation Cartwheel, the American conquest of New Georgia.

The next day, the U.S. Army and Navy began an operation to take the island away from a small Japanese garrison (less than 300 men) at Munda Point. The U.S. Army’s 172nd Infantry Regiment of the 43rd Infantry Division, along with an attached group of Solomon Island commandos, had little problem swamping the defenders.

As the troops were wading ashore, Gwin also assisted by firing at suspected Japanese positions well hidden by jungle foliage, then stood on guard to keep enemy aircraft at bay. Unfortunately, Japanese gunfire from shore batteries on Rendova returned fire and struck Gwin at 7:06 am, killing three men and wounding seven.

That afternoon, a flight of 30 Japanese planes tried to attack the invasion fleet but most were shot down. Gwin’s gunners helped to increase the total by knocking three of the torpedo bombers out of the sky. The Japanese continued on July 1 to attack the American beachhead at Rendova, but their efforts were unsuccessful.

With Rendova now secure, it was time for the Americans to move against the Japanese on New Georgia, just a few miles north of Rendova, across the Blanche Channel.

Despite the best efforts of the U.S. Navy, though, the Japanese were able to reinforce their garrison on New Georgia and stymie efforts by American ground troops to advance toward the airfield at Munda Point. While the infantry was having difficulties slugging it out in the fetid jungle, the Navy prepared once more to interdict the nightly runs of Japanese troop transports coming down from Rabaul, nearly 500 miles to the northwest.

One of those nightly runs of 10 destroyers left Buin on July 4, 1943, with orders to steam through Kula Gulf and deposit 2,600 Imperial Japanese reinforcements at Vila Point on the southern coast of Kolombangara, which was being used as a staging area for Japanese infantry before moving across the Roviana Strait to reinforce the New Georgia garrison. Leading this convoy, designated the 3rd Destroyer Squadron, was Rear Admiral Teruo Akiyama aboard the Niizuki.

On July 4, a new task group, designated Task Group 36.1, under Rear Admiral Walden L. Ainsworth, was assembled to halt Akiyama’s force. Gwin, along with Radford (DD-446), rendezvoused with three American cruisers (Honolulu [CL-48], [CL-49], and the patched-up Helena) to escort seven destroyer-transports to Kula Gulf northeast of Kolombangara, where they would land American troops at Rice Anchorage on the northern shore of New Georgia.

The opposing naval forces were on a collision course but did not yet know it.

Shortly before 2 am on July 5, the task group’s radars lit up as Akiyama’s 3rd Destroyer Squadron was picked up at a range of nearly 25,000 yards.

But Japanese radar had already discovered Ainsworth’s force 16 minutes before the American radar spotted Akiyama’s ships, and a salvo of 14 1,036-pound Type 93 Long Lance torpedoes was launched at a range of 11 miles; the American destroyer USS Strong (DD-467) was hit by one at port amidships with such force that it blew out both sides of her hull and all but broke her back. Japanese shore batteries also targeted the dying Strong; all but 46 of her men were saved after the ship sank beneath the waves.

At dawn on July 5, Rear Admiral Ainsworth, after having conducted a heavy cruiser bombardment against shore targets at Vila, was forced to retire because both fuel and ammunition were running low. As the group was retiring, the men of the Gwin spotted a life raft with five sailors from the sunken Strong and brought them to the anchorage south of Lengo Channel at Guadalcanal, where they were transferred to USS American Legion (APA-17) for evacuation. Gwin then returned to station.

Meanwhile, the Japanese had not yet given up their efforts to blow the Americans out of the Solomons. Returning the next night to Vila with a second echelon of infantry reinforcements was Rear Admiral Akiyama, with his flag again on Niizuki.

At 10 pm on July 5, General Quarters and Battle Stations were sounded aboard Gwin, and all hands raced to their assigned positions. At 42 minutes past midnight on the 6th, Ainsworth notified all his ships that an enemy force of at least six vessels had been spotted by radar. A half hour later, the two sides collided in another wild night battle that has become known as the Battle of Kula Gulf.

Within the first five minutes, the Americans hit and sank Niizuki, killing Admiral Akiyama. The three American cruisers fired almost 1,500 shells at the enemy force but the enemy destroyers picked out Helena from her muzzle flashes and hammered away at her.

Several torpedoes then slammed into Helena’s side and she began sinking and spewing oil. The destroyers Radford and Nicholas (DD-449) came to the aid of her crew and began plucking more than 750 oil-covered sailors out of the water while continuing to blast away at the enemy.

By 2:30 am, the main action was over. The Japanese had managed to land 1,500 reinforcements at Vila and then took off to the north. The Americans also retired. A naval historian wrote, “Ainsworth led his forces out of Kula Gulf, believing that he had scored a decisive victory in the Pacific. Most historians, however, believe the battle was a draw with neither side truly gaining an upper hand. American forces suffered the loss of Helena while the Japanese lost the destroyers Niizuki and Nagatsuki, but were still able to deliver more than 1,500 troops and 90 tons of supplies to Kolombangara.”

At dawn on July 6, Gwin and Woodworth returned to the scene of the battle and rescued 87 sailors before Helena keeled over and sank beneath the waves.

The skipper of the doomed Helena, Captain Charles P. Cecil, later sent a message to Fellows: “The personnel of the USS Helena, whom you helped so much, wish you to know that we shall remember your ship and her personnel with all the gratitude of which we are capable as long as we live. You may rest assured that everyone on the beach that morning offered up at least a silent prayer, when the Gwin lay to, waiting for our boats. There are no words to describe the weight which was lifted from our hearts.

“That, though, was far from being all. The efficiency with which we were cared for on board was only equaled by your kindness. At the time, all was accepted somewhat as a matter of course. Since then, we have wondered whether a much larger ship could have handled us with equal dispatch and thoroughness. Please accept our most sincere thanks, as we salute a fighting ship which took time out for an act of mercy.”

On the 11th, Gwin stood out for Rendova Island to maintain patrol. She returned to Purvis Bay the following day, refueled, and rejoined Task Group 36.1, again commanded by Ainsworth, which had been reassembled and made up of Cruiser Division 9 (Honolulu, St. Louis, and New Zealand Navy cruiser HMNZS Leander), along with 10 destroyers (Gwin, Radford, O’Bannon, Buchanan [DD-484], Jenkins [DD-447], Maury [DD-401], Nicholas [DD-449], Taylor [DD-468], Ralph Talbot [DD-390], and Woodworth [DD-460]). Lt. Cmdr. Fellows’ destroyer was ninth in the line of 13 ships that sailed into Kula Gulf early on the morning of July 13, 1943.

Their mission was to protect the amphibious landings that had been made a few days earlier on New Georgia’s northern shore, but their fate called for a different role.

Coming down the Slot from the Upper Solomons early on July 13 were more than 1,000 Japanese troops loaded onto four transports under the escort of one light cruiser (Jintsu) and five destroyers. As with the previous convoy, they were to be landed at Vila on Kolombangara.

Ainsworth thought he had achieved surprise, but the Japanese convoy, under the command of Vice Admiral Shunji Izaki, was well aware of the Americans’ presence and was prepared to do battle.

At 1 am, the two sides clashed in Kula Gulf at a point about 20 miles east of the northern tip of Kolombangara, and it was every bit as wild and bloody as had been the battle in the Slot the previous November.

While the opposing destroyers dashed about like unleashed pit bulls, the three Allied cruisers took Jintsu under concentrated fire from their main guns and the torpedoes launched by the destroyers and blew her apart. Admiral Izaki and most of her crew went down with her at about 1:45 am.

During the fight, St. Louis and Honolulu (the latter being Ainsworth’s flagship) were both seriously damaged, and Leander was hit by a Long Lance torpedo from one of the enemy destroyers and knocked out of action. Twenty six men in the boiler room and the gun mount directly above it were either killed instantly or listed as missing. Escorted by Radford and Jenkins, the crippled Leander was forced to retire from the battle.

The American destroyers, still darting about in the dark, lived up to their reputations as being feisty and fearless, thrusting at their Japanese counterparts with torpedoes and 5-inch gunfire. Gwin was in the center of the action and ahead of Honolulu.

At 2:09 am on the 13th, Fellows had to maneuver hard right to avoid another torpedo headed toward Gwin, but five minutes later Gwin shuddered as jagged pieces of her flew into the black sky; she had been hit by a Long Lance torpedo in her port quarter, knocking out her steering gear and after engine room. All radio transmitters were also knocked out and the main deck was awash.

The Navy’s official history of Gwin says, “Four Japanese destroyers, waiting for a calculated moment when Ainsworth’s formation would turn, launched 31 torpedoes at the American formation. His flagship Honolulu, cruiser St. Louis, and Gwin, maneuvering to bring their main batteries to bear on the enemy, turned right into the path of the deadly Long Lance torpedoes. Both cruisers received damaging hits but survived. Gwin was not so fortunate. She received a torpedo hit amidships in her engine room and exploded in a burning white heat, a terrible sight.”

Another naval historian wrote, “Men had been instantly slain in the destroyer’s engineering spaces where the thunderbolt exploded. Others who were trapped in wrecked compartments died in gusts of live steam or were drowned by the inrushing sea. A brave effort was made by a party led by Ensign G.E. Stransky, USNR, to control a vicious ammunition and oil fire. Searing heat and suffocating oil-smoke scorched and blinded them, but they succeeded in squelching the flames.”

The three Allied cruisers, escorted by Buchanan and Woodworth, then retired, leaving Gwin on her own, save for Ralph Talbot, which stood by to assist.

The efforts to save the listing, burning, dead-in-the-water Gwin went on into the afternoon as Lt. Cmdr. Fellows calmly directed his crew to fight the flames, but it was a losing battle. After ordering “abandon ship,” he removed himself and his crew to Ralph Talbot.

At 9:30 the next morning, Fellows and crew watched with sadness as the brave Gwin was scuttled.

Someone aboard Ralph Talbot recited the service for burial at sea as the destroyer pumped shells into Gwin, taking her down in 15 seconds along with the bodies of two officers and 59 men. Gwin had valiantly fought her last fight, and her survivors choked back tears watching her disappear.

One of her crewmen said, “She was a great ship, but we knew she’d been living on borrowed time. I guess all of us lived on that kind of time in the Solomons.”

The Battle of Kolombangara came with a heavy price tag attached: 89 Americans were killed, 61 of them on the Gwin. In addition to the loss of Jintsu and Admiral Izaki, more than 480 Japanese lost their lives. Nonetheless, the Japanese escaped with all their destroyers and were able to land 1,200 men at Vila.

To Gwin’s commander, Admiral Ainsworth later sent the following message: “My heart is very full over the loss of our Gwin after her gallant fight against terrible odds, but again you have evened the score by sinking four to six Jap ships. Once more I desire to express my unbounded appreciation and respect for the fighting ability of every officer and man in this force.

“You had proved that you had no equals when it come to putting it out and now in the battle off Kolombangara, you have proven that you can take it with a grin and wade in for more punishment. Our hats are off to the black gang and the repair parties…. Congratulations and a better than ‘well done’ to each and every one.”

For his leadership during the especially trying ordeal, Commander John B. Fellows, Jr., was awarded the Silver Star. His commendation states, “He fought his ship with deadly accuracy and unyielding determination, contributing to the sinking of four and probably six Japanese vessels…. With the utmost courage and efficiency, he directed the damage control, and with his gallant command, worked valiantly for seven hours in a desperate but futile attempt to save his vessel.”

Returning to the United States after the battle, Fellows had a short shore leave and then was given command of a newly commissioned destroyer—USS Twiggs (DD-591). Luckily for him, she was a training ship and he sailed with her out of Norfolk, Virginia, until March 1944; no more combat for Fellows. Twiggs wasn’t so fortunate, though, for on the night of June 16, 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa, a kamikaze crashed into her, and she sank with all hands.

John B. Fellows, Jr., remained in the Navy and held a variety of positions. His last assignment was as Commander, Military Sea Transportation Service (MSTS), Mediterranean Sub Area. He and his wife Harda had a son Michael and a daughter Sanna. He retired in 1959 with the rank of rear admiral and passed away on March 30, 1974, proud in knowing that he and his ship had done their part to win the war for the Allies.

Historians have argued whether the result of the Naval Battles of Guadalcanal were a tactical victory for the Japanese or the Americans, but one wrote, “The American victory in the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal effectively ended any hope the Japanese had of wresting control of the island back from the United States…. Never again would the Imperial Navy attempt to deliver a knockout blow to Henderson Field. Never again would the ‘Tokyo Express’ operate with impunity. It took an old-fashioned gunfight between two armored giants to secure the seas around Guadalcanal, now—finally—American-owned.”

And it was the men of the Gwin, and all the other ships engaged in the battles, who had paid for the victory in the seas around Guadalcanal in blood.

Michael Fellows is a retired U.S. Army colonel, Vietnam War veteran, past president of the Broomfield (CO) Veterans Memorial Museum, and son of the Gwin’s skipper, John B. Fellows, Jr.