By William B. Allmon

The British frigates HMS Orpheus and Roebuck, on April 20, 1781, escorted their prize—the Continental Navy frigate USS Confederacy—with the Union Jack flying above the Stars and Stripes, to New York harbor, thus ending Confederacy’s two-year service to the American rebels. In that short time, like other Continental Navy ships, Confederacy experienced delays in building,

fitting out, arming, recruiting sailors, shortages, and just plain bad luck.

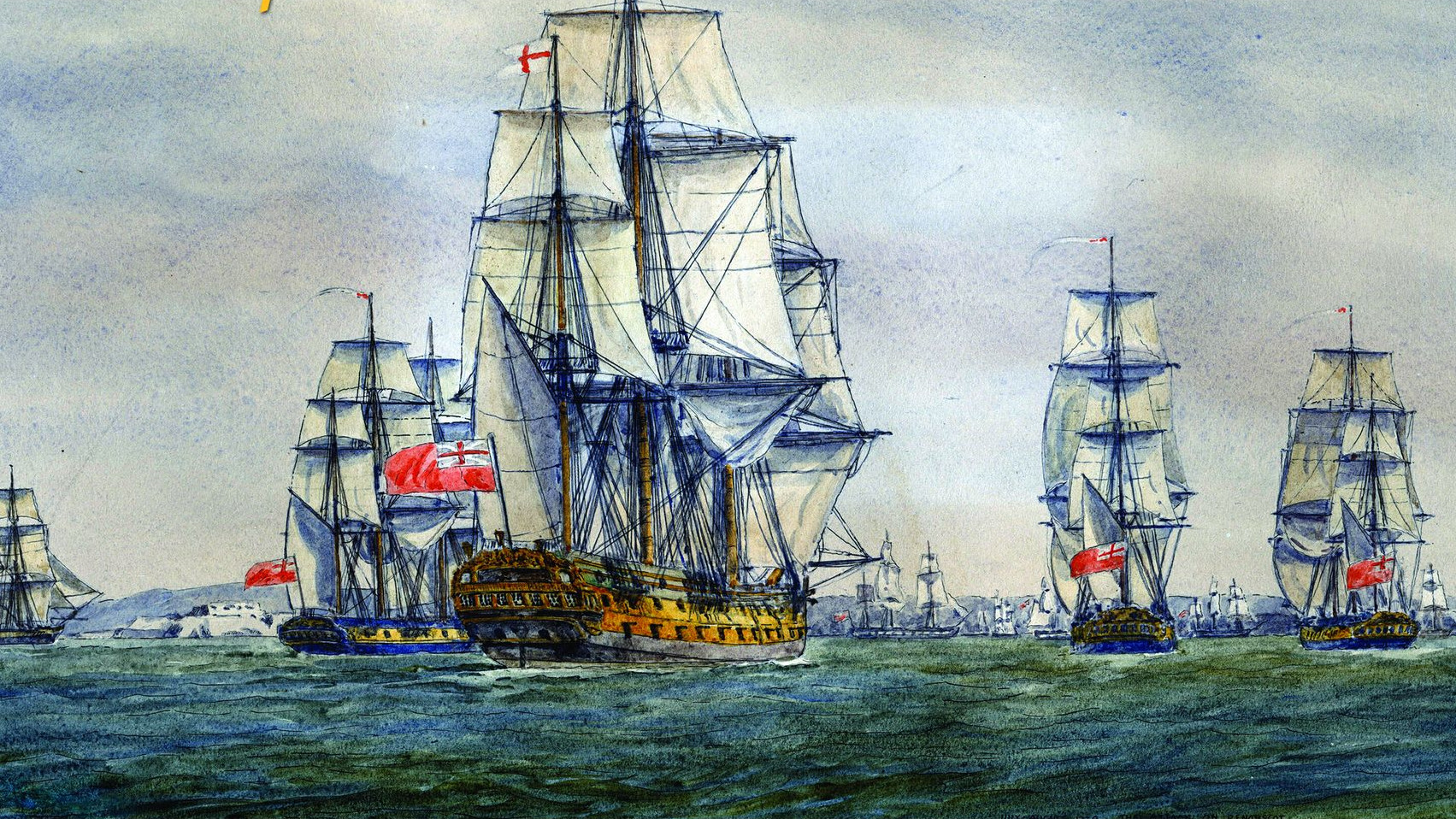

When the American Revolution began in 1775, the Royal Navy of Great Britain, with 270 ships—131 ships of the line and 129 frigates, sloops, cutters, and brigs—dominated the world’s oceans. The 13 American colonies, dispersed along the Atlantic coast, divided by navigable rivers and estuaries, were vulnerable to attack by sea. Using the Royal Navy and a few marines, the British easily should have been able to crush the American Revolution. Only distance, long supply lines, and badly neglected and manned ships kept the British from decisively exploiting their superior naval force.

The American rebels, the British were certain, would be unable to raise a navy capable of winning a maritime war. Except for a few small state navies established to protect their home waters, the American colonies had no organized navy to take on the Royal Navy. In fall 1775, the Continental Congress, meeting in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, began looking for means to protect their shores from attack by the British.

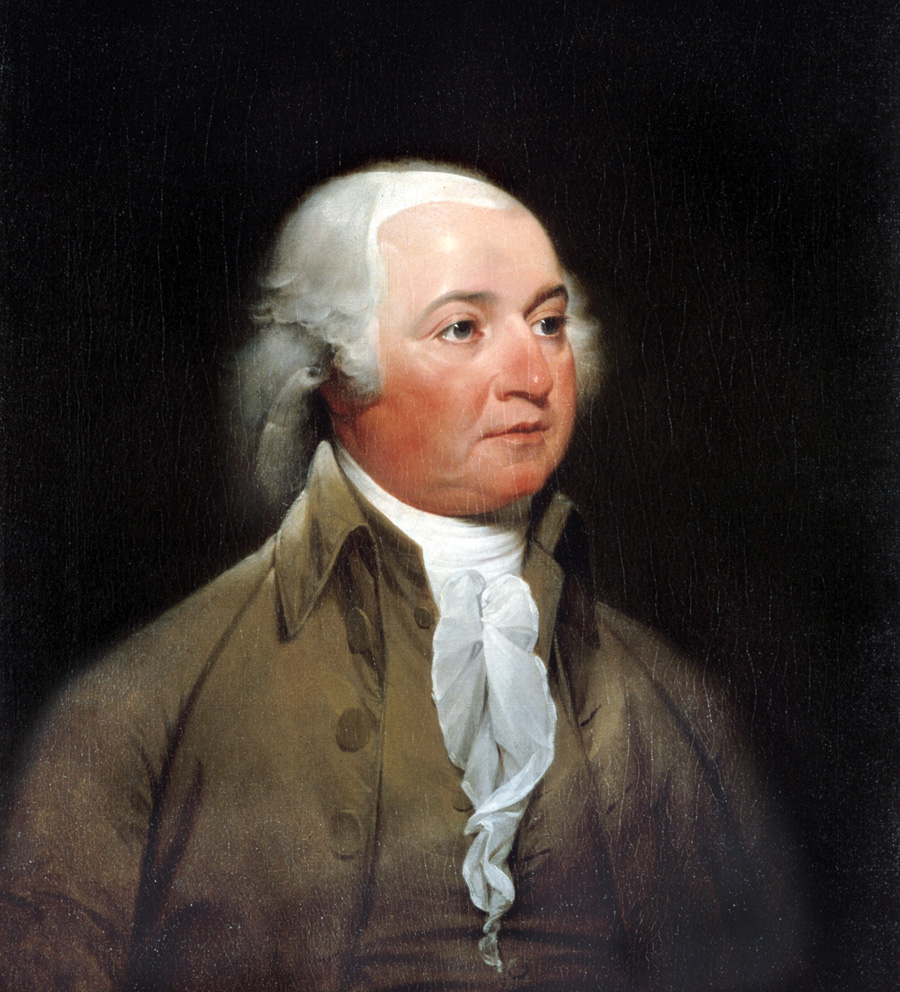

On October 3, 1775, Congressman Stephen Hopkins of Rhode Island introduced a resolution calling for the “building of a fleet of sufficient force for the protection of these colonies,” to be employed “in such a manner and places as will efficiently annoy our enemies.” After two weeks of raucous debate, Congress on October 30 authorized the conversion of four merchant ships into warships, appointing John Adams, a staunch advocate of naval power, and six other Congressmen to a naval committee to draft rules to govern the American navy.

Adams presented the draft to Congress on November 23, 1775, recommending $60,000 be set aside to build frigates. Congress passed the resolution establishing the Continental Navy and appointing a 13-member Marine Committee, one member from each colony to oversee the fleet. The Continental Navy, once established, would be able to pursue and attack any enemy men-of-war and transports. But before any prizes could be captured or men-of-war sunk, the new Continental Navy needed ships. On December 13, 1775, Congress authorized the construction of 13 frigates—five with 32 guns, five with 29 guns, and three with 24 guns—to be ready for service by the end of March 1776.

Lack of funds determined that only frigates, ships with one or two decks, used mainly for scouting and escort duties, could be built. By March 1776, despite having large tracts of land with a variety of huge trees, including white oak for building warships, due to serious shortages of naval stores and equipment and lacking experienced shipwrights, none of the original 13 frigates was ready. The first Continental frigate, Warren, was launched at Providence, Rhode Island, on May 15, 1776; the last frigate, Washington, was completed in September 1776, but with few exceptions, the Continental Navy was stuck in port waiting for provisions, ordnance, rigging, and crews.

Despite this, on November 30, 1776, Congress ordered the construction of three 74-gun ships, five 36-gun frigates, three sloops of war, and an 18-gun brig. Two of the 74-gun ships, three frigates, and the brig were never completed due to shortages of money and materials. Work proceeded slowly on the remaining ships, including the frigate Alliance, in Salisbury, Massachusetts, and Trumbull in Norwich, Connecticut.

In January 1777, Congress authorized the building of a second Continental Navy frigate in Norwich. Construction of the new frigate began in the spring. In September, Congress and the Marine Committee decided to name the new frigate Confederacy.

The same day she was named, Congress selected Seth Harding of Norwich as Confederacy’s captain. Born in Eastham, Massachusetts, on April 17, 1734, Harding went to sea early in life and prospered in the West Indies trade. When the revolution began, Harding took command of the 14-gun brig Defence based in New London, Connecticut, and successfully attacked British ships between Connecticut and Long Island.

In September 1776, securing the aid of Connecticut Governor Jonathan Trumbull, Harding applied for a captain’s commission in the Continental Navy. After voting to name the new ship, Congress elected Harding captain of the frigate Confederacy.

Confederacy was finally launched on November 8, 1778, after a year’s construction. At 153 feet long with a beam of 135 feet, 6 inches, and displacing 950 tons, the new frigate was designed for speed and was larger than frigates used by other navies. After launching, she was towed down the Thames River from Norwich to New London, where her three masts were set up and her guns mounted.

While Confederacy was made ready, Harding, along with Lieutenant Gurdon Bill, and Joseph Hardy, captain of Confederacy’s Continental Marine detachment, concentrated on recruiting a crew. Competing with local privateers for the available sailors, Harding found recruiting difficult. Unlike the lax discipline, high wages, and a chance for prize money offered by privateers, the Continental Navy paid low wages, had strict discipline, and prize money was divided between the government and a ship’s crew.

Along with raising a crew, arming Confederacy was another problem. She was designed to carry 36 guns—28 12-pounders and six 6-pound guns—supplied from the foundry at Salisbury Furnace, Connecticut. However, because of technical problems, they failed to deliver the armament. The order was transferred to a Massachusetts iron works, which also could not deliver Confederacy’s guns to New London in time. Eventually, as they did for other ships, the Navy Board’s Eastern Department in Boston was forced to scrounge for cannons. By exchanging cannons with other Continental ships, using captured British guns, and adding cannons bought in France, Confederacy eventually mounted 28 guns on the main deck, six on the quarter deck, and two on the forecastle.

Recruiting a crew remained Harding’s biggest difficulty. A recruitment announcement in a New London newspaper failed to produce the full complement of 260 sailors needed to go to sea, so Harding sent patrols into New London to round up deserters and press sailors into service. Although not unusual, the Continental Navy resorted to impressment far less than the Royal Navy. One patrol rounded up French prisoners released by the British; another patrol brought in 50 sailors. Some of the impressed men were later released, while the rest remained on board Confederacy.

Unhappy with his lack of progress preparing Confederacy, on April 17, 1779, the Navy Board ordered Harding to put to sea. On May 1, 1779, undermanned and short of supplies, Harding took Confederacy to sea for the first time and turned south for Delaware Bay, training Confederacy’s green crew in seamanship, gunnery, and battle tactics.

Several weeks later, on June 2, 1779, Confederacy sailed up Delaware Bay to Lewisburg, Delaware, where Harding received orders to join Captain Samuel Tucker’s frigate Boston on a three-week cruise off the coast, where they were to destroy as many enemy ships as possible. The frigates also were ordered to escort a fleet of merchant vessels carrying supplies from the West Indies for the Continental Army into Delaware or Chesapeake Bay ports. After receiving their orders, Confederacy and Boston, flying the new 13 stars and stripes American flag, plus the Continental Navy’s Rattlesnake ensign, left Delaware Bay and sailed into the Atlantic.

Two days out, Confederacy’s lookouts sighted a merchant convoy pursued by two British frigates. Tucker signaled Confederacy to attack one frigate, while Boston took on the second. Confederacy’s crew quickly cleared the frigate’s decks for action, while she and Boston sailed past the convoy toward the British ships. The British frigates, sighting the American frigates bearing down on them and determining that they would be overpowered, gave up the chase.

Boston and Confederacy escorted the convoy safely to Delaware Bay and resumed their cruise. Several days later, on June 6, 1779, they sighted a ship resembling one of their recent opponents. Hoisting British colors, Confederacy and Boston bore down on the 26-gun British privateer Pole. Once in range, Boston and Confederacy struck their British flags and hoisted American colors. Tucker demanded the privateer’s surrender. Outnumbered and outgunned, Pole surrendered without firing a shot. “In company of the Boston captu’d a privateer of 24 guns and upward of 100 men on board,” Harding wrote in his log.

Escorted by Confederacy and with a prize crew from Boston on board, Pole set sail for Philadelphia. Later that same day, Confederacy captured the English schooner Patsy and sloop William bound for New York from the West Indies. Confederacy escorted the three prizes to Philadelphia then rejoined Boston at sea.

On July 2, 1779, Confederacy and Boston joined Captain Samuel Nicholson’s frigate Deane in Chesapeake Bay to search for a rumored British naval force. Finding nothing, Confederacy returned to Delaware, while Deane and Boston patrolled off British-held New York. Confederacy returned to sea on August 24, 1779, searching for the Continental brig Eagle carrying supplies from St. Eustatius Island, West Indies. Finding Eagle off the Delaware Capes, Harding escorted her safely into port.

Harding sailed Confederacy to Chester, Pennsylvania, on September 8, 1779, and waited for instructions. His orders arrived on September 17. Confederacy was to carry Conrad Alexandre Gerard, French minister to the United States from the court of King Louis XVI, home to France. During the passage, Harding was to avoid engaging enemy vessels, comply with Gerard’s wishes, and treat him with all the respect due his stature.

A month later, on October 17, 1779, Harding was informed that John Jay, former president of the Continental Congress, newly appointed American ambassador to Spain, with his secretary and family, would be traveling with Gerard on Confederacy. During the voyage, Harding was instructed to consult with Jay and Gerard and “be governed by their orders in respect to any occurrence which may happen and the port to which you are to proceed.”

John Jay, his wife Sarah, and his entourage boarded Confederacy at Chester on October 20. Minister Gerard and his party arrived five days later. Once his distinguished passengers were settled in, Harding raised anchor on October 26 and took Confederacy to sea.

In the Atlantic from October 27 to November 6, Confederacy enjoyed 12 days of smooth seas and pleasant sailing. By November 7, 1779, Confederacy was making nine knots under a brisk wind and steadily growing seas. “It was blowing a fresh gale, the ship close to the wind under courses,” Confederacy’s Sailing Master John Tanner recalled.

Tanner was on watch at 5 am, November 7 with Seaman William McLaughlan when he saw the bowsprit starting to break. Tanner quickly ordered Confederacy turned into the wind to save the mast. Before the turn could be made, the foremast, Tanner remembered, “in less than half a minute fell over to leeward quite clear of the ship.” Tanner then heard the mainmast crack; it fell over him, covering him in a mass of “mast yards, rigging and sails.” Before he could get free, Tanner heard Confederacy’s mizzen mast break and topple over the quarterdeck.

Hearing what Sarah Jay called an unusual noise on deck, Harding and his crew hurried up from below. “It was unnecessary to call all hands to the deck,” Howard observed. In three minutes, because of poor quality timber, Confederacy had lost her bowsprit, fore, main and mizzen masts, leaving the frigate dismasted at the mercy of gale force wind and waves.

“We all turned to with a will,” Tanner wrote. Over the next six hours, while Confederacy’s quartermasters William Kingston and Abel Spicer tried to control her rolling, her sailors cut away the snapped spars, sails, and cables, behaving “exceedingly well on this occasion,” Harding reported. Once the wreckage was cleared, they attempted to jury rig a mast on Confederacy’s furiously tossing and rolling decks. Unless the crew could establish some degree of steerage and reduce the roll, the ship was in grave danger of foundering.

By evening the crew had rigged, Tanner recalled, “some sail on the stump of the mizzenmast” and a sea anchor to “keep the ship to the wind as it blew a gale.” With her small masts, Confederacy rode out the storm all night. “The ship labored very much for want of the mast,” Tanner remembered. “The decks [were] full of water all night.”

At dawn on November 8, the crew found that Confederacy was not responding to her rudder, leaving the ship helplessly wallowing in the heavy seas. The shank of Confederacy’s rudder connecting it to the helm had split, leaving the rudder to bang freely against the stern, opening holes through which water flowed.

Harding set his crew to rigging a new rudder connection. With considerable trouble, Confederacy’s sailors managed to link chains through a ring and bolt below the split shank and steer the ship, but the bolt broke under the strain, leaving Confederacy again out of control. For two weeks, while Confederacy drifted east with wind and currents, her crew tried to jury rig her helm to her rudder. Working over the ship’s side, Confederacy’s sailors threaded two lengths of chain through two eyebolts on the frigate’s rudder, connecting them to lines passing through blocks on spars mounted on the stern, and in turn securing to blocks on the weather deck. Using these lines to move her rudder, they brought Confederacy under control, although the strain caused the lines to frequently snap.

On November 23, 1779, Harding called a council of his officers to decide if they should sail to Europe or to the nearest safe port. By now, Confederacy was 1,140 miles from Delaware Bay, well out into the Atlantic. Given the chronic steering problems, the council agreed Confederacy was in no shape to sail to Europe. In her present condition, they said, it was prudent to proceed to the French colony of Martinique in the West Indies.

Harding turned Confederacy south toward Martinique, limping under makeshift masts, her crew manning the pumps constantly to keep ahead of the water leaking through the stern. The weather remained calm during Confederacy’s passage to Martinique. Confederacy was also lucky not to encounter a British warship in her damaged condition.

Harding brought Confederacy into St. Pierre, Martinique, on Saturday, December 18, 1779, 53 days after leaving Delaware Bay. Harding had used all his skills as a captain to get his badly crippled ship across 1,400 miles of open sea. Both crew and passengers were relieved to have arrived in Martinique.

When Confederacy anchored, she was met by American naval agent William Bingham, who put Jay’s family into his own house and arranged for Confederacy’s repairs. On December 22, five days after arriving in St. Pierre, Bingham, Jay, and Harding called on Martinique’s Governor François Claude Amor, Marquis de Bouille, in the capital of Fort Royal. De Bouille promised them no effort would be spared to repair Confederacy, as if she were a French frigate. Confederacy sailed from St. Pierre to Fort Royal on December 26 and tied up at the French naval station.

Three days later, John Jay and his family joined Gerard aboard the French frigate Aurore and sailed to Cadiz, Spain, going from there to Madrid. Confederacy remained in Fort Royal through February 1780, as repairs were made on her splintered rudder, and attempts to set up temporary masts were made. None were stored at Fort Royal, and those that were available were used to repair damaged French warships. New masts, Harding reported, were “very difficult to obtain and some impossible to be had at this place.”

Despite everything, Harding reported by February 18, “I have obtained such necessities for the ship’s outfit as are to be had in this place.” Confederacy’s makeshift masts were ready for sea by March 13, 1780, and Harding took her to sea, intending to sail to Boston, where he believed “spars of the best quality abound in great plenty.” Before setting course for Boston, Confederacy returned to St. Pierre to pick up additional supplies.

After taking on a cargo of sugar and cocoa, with Bingham aboard as a passenger, Confederacy set sail for Philadelphia on March 30, escorting a convoy of five merchant ships. Five days after leaving Martinique, Confederacy sprung her foremast in a heavily rolling sea. Her small, jury rigged masts, Howard observed, could “hardly be called in first class trim.” But, remembering her earlier dismasting, Confederacy’s crew, Hardy wrote, considered this a “trifling circumstance.”

Confederacy’s sprung mast forced Harding, one officer recalled, to “treat his makeshift rigging gingerly, lest he find himself once again dismasted.” Several ships were sighted but were allowed to pass unchallenged; the frigate’s inferior rigging made pursuit impossible. The rest of Confederacy’s voyage passed uneventfully.

Approaching the American coast, the ships of the convoy scattered to their various destinations, while Confederacy continued to Cape Henlopen, Delaware, arriving on April 25. Two days later, a river pilot guided her to Philadelphia.

As Confederacy began her refit, the Continental Navy’s fortunes reached their lowest point. Both 1779 and 1780 were bad years for the navy; half a dozen ships were lost to the British, and there was little money for the navy to build new ships or repair older ones. Officers and men were paid in devalued paper currency. A greater blow fell on May 12, 1780, when 5,000 Continental troops under Maj. Gen. Benjamin Lincoln, along with the frigates Providence, Boston, Queen of France, and Ranger, surrendered to a British army led by General Henry Clinton at Charleston, South Carolina. The loss of these four ships, Miller said, “all but eliminated the Continental Navy as an effective fighting force.” By summer 1780, only the frigates Trumbull and Deane in New England, Confederacy refitting in Philadelphia, the frigate Alliance in Europe, and the new sloop Saratoga in Delaware remained.

Confederacy spent summer and fall 1780 alternating between Philadelphia and Chester, trying to get back to sea. By the end of November 1780, with an unexpected influx of money from a cargo of rum captured by Saratoga, and after seven months in port, Confederacy’s rerigging was completed.

The Saratoga, commanded by Captain John C. Young, escorting a 13-ship convoy heading for the West Indies, joined Confederacy off Reedy Island, Delaware. On December 20, 1780, both vessels escorted the convoy into Delaware Bay, until Confederacy’s pilot, deciding the weather was too rough for her to venture out to sea, turned Confederacy back to Delaware Bay, leaving Saratoga to escort the convoy alone.

Confederacy got underway the following day, December 21, and headed into the open sea. Despite her refit, Confederacy did not sail well under her new rigging. Several days out at sea, she once again sprung her mainmast, forcing Harding to shorten sail when the wind freshened or risk its collapse.

At noon, January 8, 1781, Confederacy’s lookouts sighted a sail in the distance. Harding gave chase, and by 10 pm, Confederacy was alongside the brig Elizabeth and another vessel, Nancy, commanded by Captain Clifford Bryce, from Liverpool, Nova Scotia, bound for Turks Island in the British-held Bahamas. The ships were escorted to Cape François, Haiti, where a French Admiralty Court determined that the Elizabeth and Nancy had been legally captured. But neither Harding nor Confederacy’s crew received any prize money for the capture.

On February 1, 1781, under orders of the island’s governor, Confederacy left Haiti with the French brig Cat to hunt for British ships. After a two-week cruise, encountering only American vessels, Harding returned to Cape François on February 16. There Confederacy joined Saratoga, the frigate Deane, and the privateer Fair American, which, along with Cat, formed what one sailor called “a formidable squadron.”

The squadron left Cape François on February 20 and patrolled the Windward Islands, seeking British ships. They soon captured the British merchant ship Diamond, bound from St. Kitts to Jamaica with a cargo of dry goods and slaves. Confederacy and Saratoga also captured a 20-gun cargo ship sailing from St. Eustatius to Jamaica. After this action, Confederacy, Saratoga and Deane returned to Cape François, where they waited for several weeks while a convoy of American and French merchant ships assembled.

The 77-ship convoy—37 American and 40 French merchant ships—left Cape François on March 15, 1781, escorted by Confederacy, Deane, and Saratoga. Four days later, the French ships parted company with the Americans and headed for Europe. A short time later, Saratoga chased two British merchant vessels, capturing one and continuing after the second, leaving Confederacy and Deane escorting the convoy. Saratoga never returned; Deane lost the convoy in a storm and made her own way to Boston, leaving Confederacy escorting the merchantmen alone.

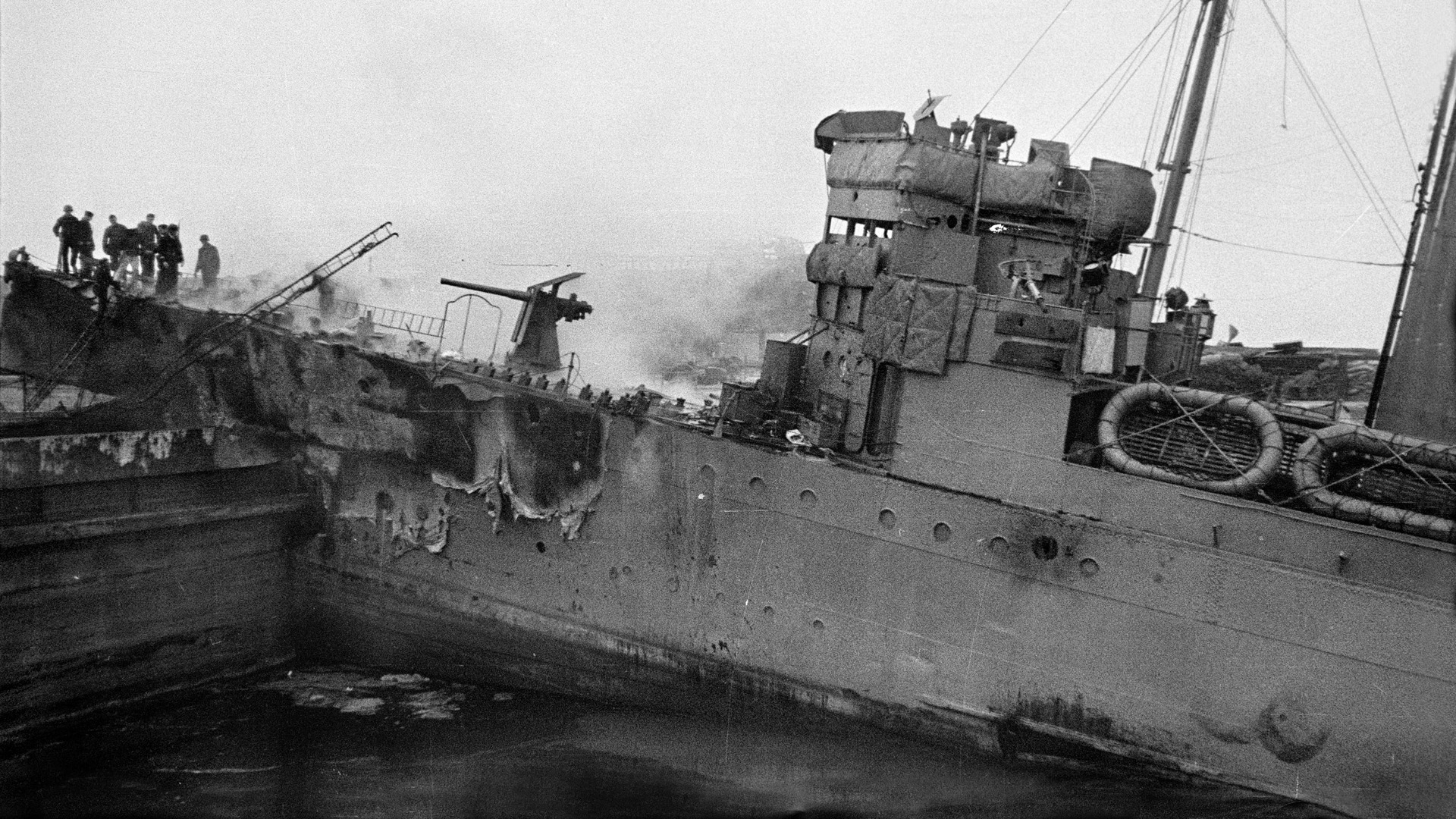

Confederacy was herding her charges along near the Delaware Capes on Saturday, April 14, 1781, when Harding sighted a large ship bearing down on the convoy. Harding cleared Confederacy for action, ordered the merchant ships to scatter, and steered toward the approaching ship. Unexpectedly, another vessel came over the horizon following the first. The second vessel was the 44-gun frigate HMS Roebuck under Captain Andrew Snape Douglas. When they were in range, Roebuck and Captain James Richard Dacres’s 32-gun frigate HMS Orpheus broke out British colors and ran out a second deck of guns. Alone, faced by their overwhelming firepower, Harding struck Confederacy’s colors without resistance. Thus ended the ship’s brief and troubled career in the Continental Navy. Several merchant ships from the convoy were also captured. The rest escaped.

After putting a prize crew aboard, Roebuck and Orpheus escorted Confederacy to New York, arriving six days later, on Thursday, April 20, 1781. “The captain of the rebel frigate must escape every imputation derogatory to the conduct of an officer and a man of honor,” a New York newspaper commented. “We must allow even an enemy merit, when he is not found justly to have forfeited it.”

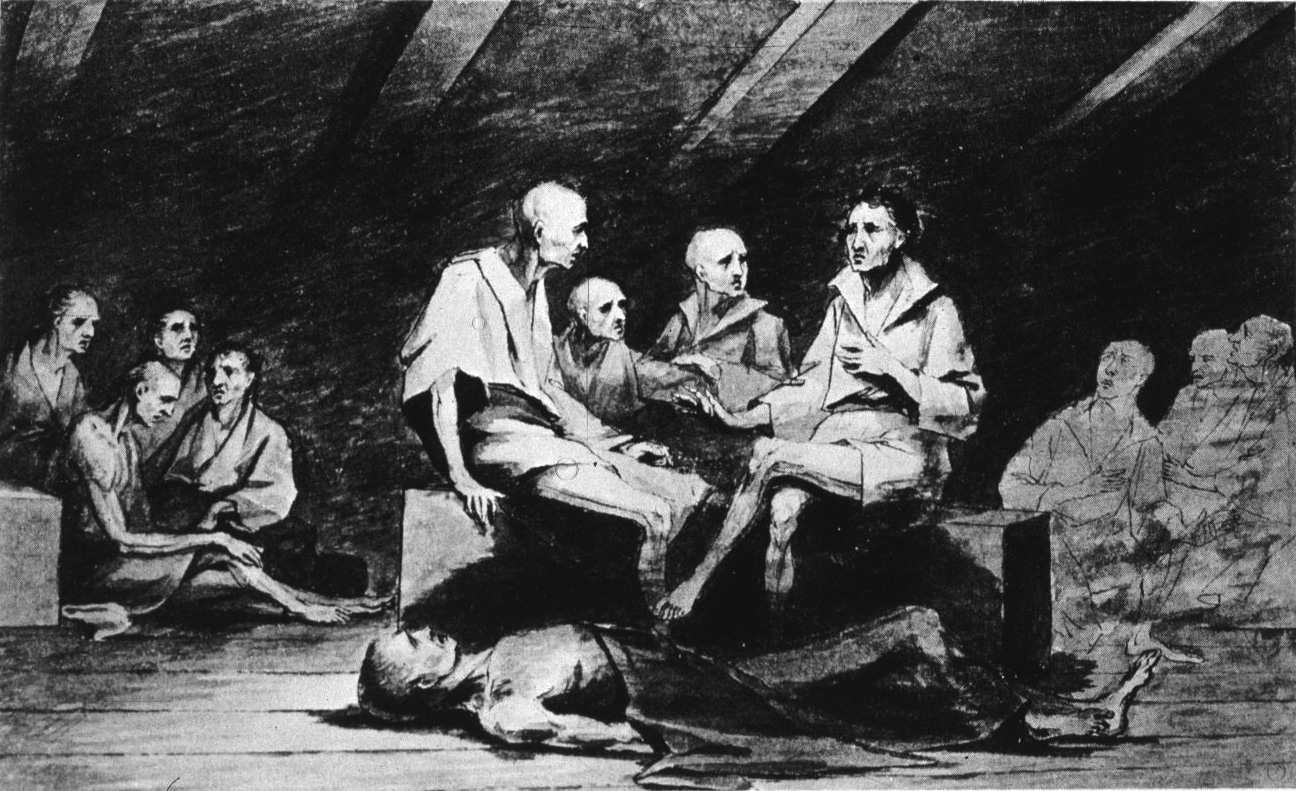

Most of Confederacy’s crew was confined aboard the prison ship Jersey in New York harbor, where many died of disease and malnutrition. Those of the Confederacy’s sailors who survived remained aboard Jersey until they were exchanged, joined the British service, or were released.

Marine Captain Hardy, Lieutenant Bill, and other junior officers were sent to England on a Royal Navy ship to be imprisoned. When the ship accidentally put into an Irish port, Hardy and Bill escaped, making their way to France and eventually back to America.

Captain Harding, along with 100 American prisoners, was paroled and sent to New London in a prisoner exchange on May 4, 1781, his navy career finished. In November 1781, Harding invested in the Connecticut privateer Young Cromwell, which was captured on her first voyage. He next commanded the six-gun corvette Diana in October 1782, only to be captured by a British man-of-war. After the revolution, Harding became a merchant sailor and retired to Schoharie, New York, where he died on November 20, 1814.

Of the original 13 frigates built for the Continental Navy, seven, including Confederacy, were captured; four were burned to prevent their falling into British hands. Only the frigate Deane remained at the end of the Revolutionary War in 1783. The Americans had expended vast amounts of money and manpower building, arming, and victualling warships that failed to hamper the operations of the superior Royal Navy.

Confederacy was placed into service with the Royal Navy under the name HMS Confederate. In June 1781, the newly commissioned Confederate sailed to England, where in mid-July she was declared unfit for service and placed in reserve. Seven years later, in March 1787, the former Confederacy was broken up. Her fate may not have been what the nation had hoped for, but it accurately reflected the general fortune of the Continental Navy’s first frigates.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments