By Roy Morris Jr.

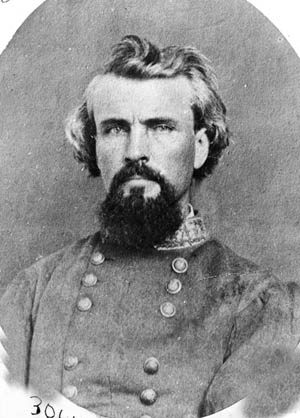

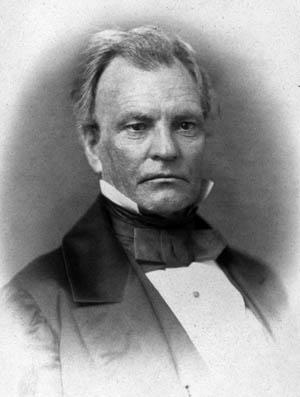

When Confederate Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest and his 3,000 battle-hardened troopers rode back into their homeland of West Tennessee in late March 1864, they were not in the best of moods. A horse-gathering raid into Kentucky had netted a haul of 400 horses and mules for a new division of Bluegrass cavalry, but it had also seen the death of Colonel A.P. Thompson during an unsuccessful—and unordered—attack on Union-held Fort Anderson on the Ohio River near Paducah.

Forrest had already withdrawn from the smallpox-ravaged town before the attack, but that did not prevent pro-Northern newspapers from crowing about the comparatively minor skirmish at Forrest’s expense. The Louisville Journal, labeling the Paducah raid an abject failure, charged that Forrest’s men had been “gloriously drunk, and but little better than a mob.” The paper accused the raiders of “commencing an indiscriminate pillage of the houses” before making “several desperate charges” upon the fort. “The Federals met them with a withering fire, and in each onset the rebel columns were broken and driven back in confusion.”

That was bad enough, but the staunchly abolitionist Chicago Tribune leveled the explosive accusation that Forrest’s men had “skedaddled, after killing as many Negroes as they could, which seems to have been their primary object in coming to Paducah.” Even worse in Southern eyes was the newspaper’s provocative claim that Forrest and his men had been “ignominiously beaten back by Negro soldiers with clubbed muskets.” Further rubbing salt into the wound were false reports that Colonel Thompson, a well-liked young officer, had been killed by a musket ball to the forehead fired by “an ardent young African.” (Actually, Thompson was killed by a shell from a Union gunboat.)

To a man, Forrest’s soldiers seethed at the bogus reporting, which neglected to mention the surrender of a Federal detachment at Union City, a crossroads village in northwestern Tennessee, earlier in the raid. There, Colonel William L. Duckworth, posing as Forrest, had bluffed garrison commander Colonel Isaac Hawkins into capitulating without a fight. Hawkins, despite holding a strong opposition, had handed over himself and 500 other Union soldiers along with 300 horses and $60,000 in greenbacks that the garrison had recently received in pay. The Confederates joked afterward that they would be happy to parole Hawkins in order to obtain more horses and equipment the next time they needed them.

The Atrocities of Fielding Hurst

Riding back into their home state—Forrest and most of his men were native West Tennesseans—the returning horsemen were besieged by their hard-pressed friends and neighbors to do something about ongoing Federal abuses in the area. Two years of Union occupation interspersed with Confederate raids and counterraids had spawned a poisonous atmosphere of revenge and reprisal that hung over the entire region like an evil cloud. “The whole of West Tennessee,” Forrest reported angrily, “is overrun by bands and squads of robbers, horse thieves and deserters, whose depredations and unlawful appropriations of private property are rapidly and effectually depleting the country.” The land itself, usually green and fertile in the spring, was picked over and brown, dotted with burned farmhouses and ruined barns.

Making camp at Jackson, Forrest received a delegation of local residents who brought word of an ongoing campaign of plunder, blackmail, and destruction by a regiment of “renegade Tennesseans” led by Colonel Fielding Hurst of the 6th Tennessee (U.S.) Cavalry. According to the townsfolk, Hurst had demanded and gotten a sum of $5,139.25 from Jackson residents in return for a promise not to burn the town to the ground. The sum was precisely, to the penny, the amount Hurst had been fined by authorities in Memphis for destroying a local woman’s property during a previous raid.

Even worse than Hurst’s extortion demands, Forrest learned, was the colonel’s brutal treatment of several Forrest subordinates who had returned to their hometowns to recruit new soldiers for the Confederate cause. Hurst had murdered seven of the recruiters in the past two months, including a well-liked young lieutenant named Willis Dodds, who had been killed less than two weeks earlier at his father’s home in Henderson County. According to reports, Dodds had been tortured to death and “most horribly mutilated, the face having been skinned, the nose cut off, the under jaw disjoined, the privates cut off, and the body otherwise barbarously lacerated and most wantonly injured.”

A furious Forrest issued a proclamation formally labeling Hurst and his troopers as outlaws and declaring that they were “not entitled to be treated as prisoners of war falling into the hands of the forces of the Confederate states.” Instead, he said, Hurst’s men would be shot down summarily whenever and wherever they were captured. Union authorities in Memphis warned Hurst “against allowing your men to straggle or pillage, as a deviation from this rule may prove fatal to yourself and your command.”

“Homemade Yankees” of Fort Pillow

The Jackson delegation also told Forrest about another “nest of outlaws” currently holed up in an abandoned Confederate fortification, Fort Pillow, overlooking the Mississippi River 40 miles due north of Memphis. These Unionists, members of the 13th Tennessee Cavalry, were under the command of Major William F. Bradford, another West Tennessee Unionist from Forrest’s namesake home county of Bedford. The unit contained many “homemade Yankees,” former Confederates who had joined forces with the occupying Federals. The turncoat cavalrymen were roundly detested by Forrest’s men, many of whose families reportedly had been victimized by Bradford’s men through threats, abuses, and outright thievery. “Under the pretense of scouring the country for arms and rebel soldiers,” Forrest reported, Bradford had “traversed the surrounding country with detachments, robbing the people of their horses, mules, beef cattle, beds, plates, wearing apparel, money, and every possible movable article of value, besides venting upon the wives and daughters of Southern soldiers the most opprobrious and obscene epithets, with more than one extreme outraged upon the persons of these victims of their hate and lust.” It was the worst charge that could be leveled against a supposed gentleman of the time, and it virtually demanded immediate revenge.

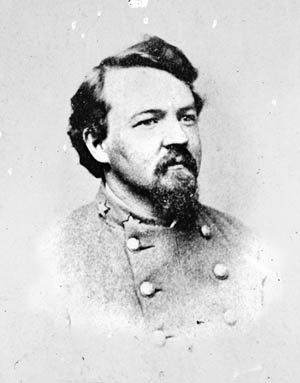

Promising to attend to the Federals at Fort Pillow “in a day or two,” Forrest ordered Brig. Gen. James Chalmers to bring up the rest of the cavalry corps from its base camp in northern Mississippi. Chalmers, a diminutive attorney in civilian life—his men affectionately called him “Little Un”—quickly obeyed. The first order of business was dealing with the much hated Hurst and his renegade Tennesseans. On March 29, Forrest subordinate Colonel James J. Neely trailed Hurst to Bolivar, Tennessee, and overran his camp with a swift surprise attack. As Chalmers reported later, “Colonel Neely met the traitor Hurst at Bolivar, after a short conflict, in which we killed and captured 75 prisoners of the enemy, drove Hurst hatless into Memphis and captured all his wagons, ambulances and papers, as well as his mistresses, both black and white.” As subsequent events at Fort Pillow would prove, Hurst got off lightly with the mere loss of his hat and his girlfriends.

To lock Federal forces into place while he advanced on Fort Pillow, Forrest sent Colonel Abraham Buford back to Paducah, Kentucky, to seize the remaining 140 U.S. horses that Northern newspapers had bragged about the Rebels missing on their last go-round. Forrest also ordered Neely to pin down the Union garrison at Memphis. Meanwhile, Forrest personally headed west toward Fort Pillow with the remainder of his formidable command in a driving rainstorm. The bad weather did not improve the soldiers’ moods.

“I Can Hold the Post Against Any Force For Forty-Eight Hours.”

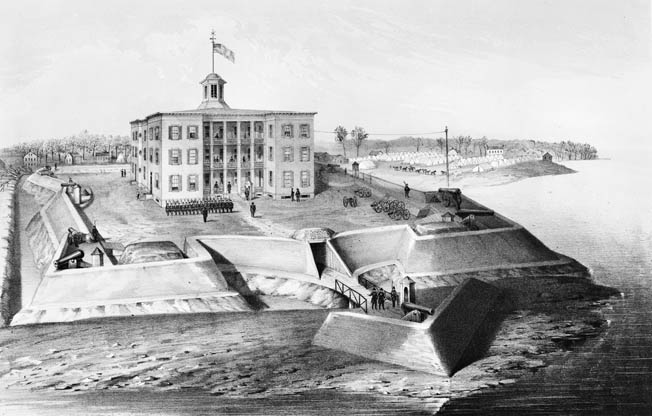

Fort Pillow, constructed in 1861 on the east bank of the Mississippi River, was named after Confederate Brig. Gen. Gideon Pillow, another native Tennessean. It stood immediately below the intersection of the river and Coal (or Cold) Creek and featured three lines of earthen entrenchments—a semicircular outer line of earthworks, a shorter second line atop a prominent hill, and the fort itself, with earthworks six to eight feet high and four to six feet across. A 12-foot-wide, six-foot-deep trench fronted the fort. The fort’s earthworks extended in a 125-yard-wide semicircle, behind which the land fell away rapidly to the river. Deep ravines crisscrossed the landscape in front of the fort, and four rows of barracks stood on an open terrace of land southwest of the bastion.

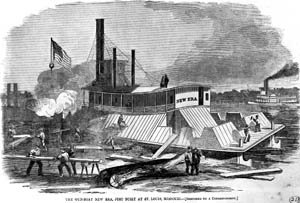

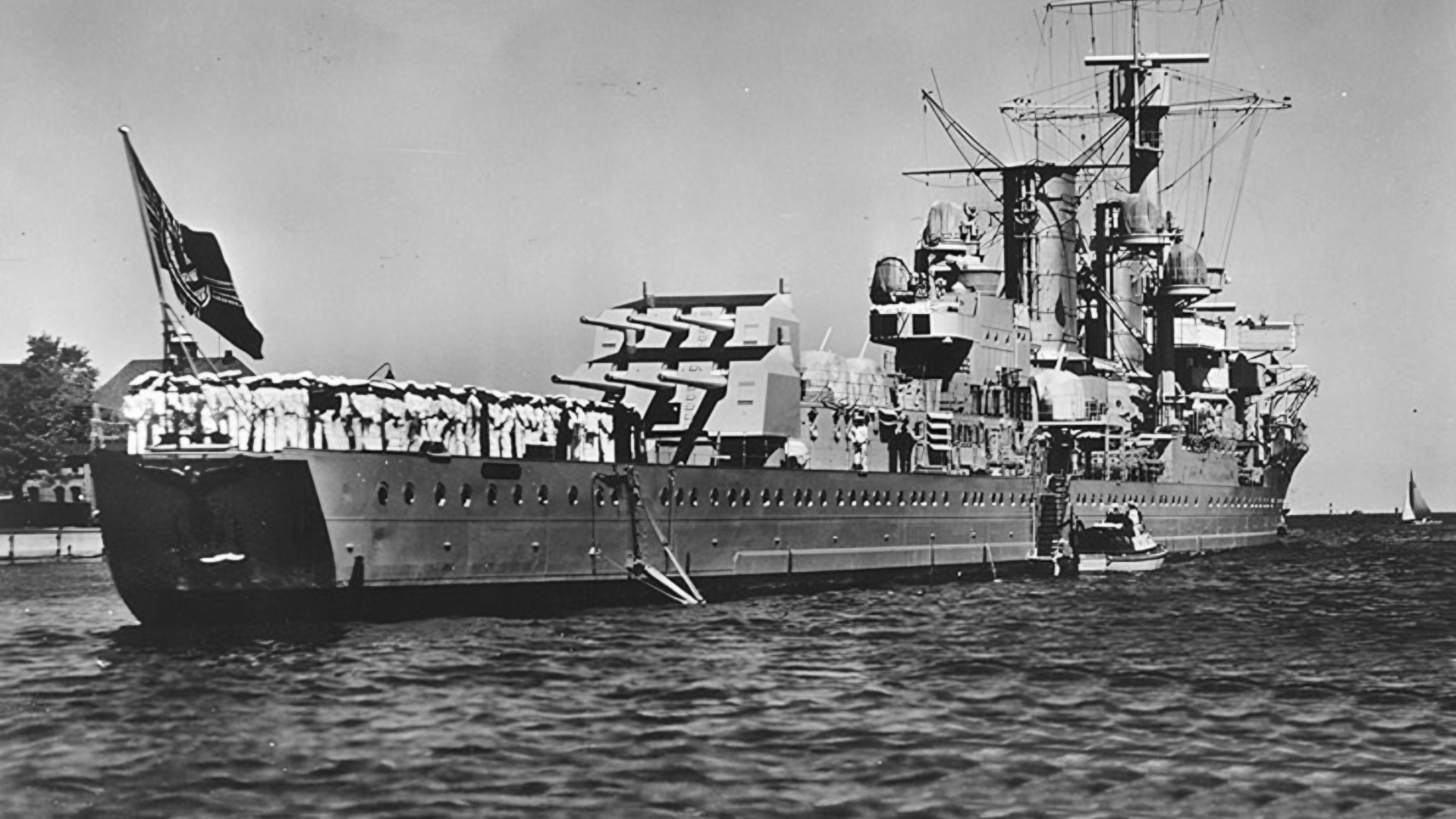

The fort had been abandoned by the Confederates after the fall of Corinth, Mississippi, in May 1862. Since then, Union forces had occupied the stronghold intermittently without bothering to strengthen or expand it beyond throwing up some more rifle pits and gun platforms. The presence of the Union gunboat New Era, anchored just offshore and commanded by Captain James Marshall, added to the defenders’ false sense of security. As Forrest advanced implacably toward it, Fort Pillow now was garrisoned by 580 soldiers in three separate units. The 13th Cavalry, under Major Bradford, had quartered there for the past two months while recruiting new members and continuing to terrorize Confederate sympathizers in the region. Bradford’s force was joined by two African American artillery units—the 6th U.S. Heavy Artillery and the 2nd U.S. Light Artillery, manning six pieces of artillery. The ill-starred black gunners had only been at the fort for two weeks and had taken no part in the cavalry’s ongoing depredations. Fairly or not, they would share in the blame.

Fort Pillow’s garrison was commanded by Major Lionel F. Booth, a Philadelphia native and Regular Army veteran of the Battle of Wilson’s Creek. His appointment did not sit well with Bradford, who was also a major but was a few weeks shy of Booth in seniority. In truth, neither of the officers nor their men should have been there at all. Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, who needed every available man for his upcoming Atlanta campaign, had pointedly ordered rear-echelon commanders to abandon strategically unimportant forts such as Fort Pillow. But Memphis-based Maj. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut had ignored Sherman’s order and sent Bradford’s and Booth’s men into the fort anyway. The suspicion, although never proved, was that Hurlbut was involved in the lucrative cotton-smuggling trade—Northern mills were paying up to 80 cents per pound for cotton—and was using Fort Pillow as a convenient distribution point. If so, Hurlbut’s subordinates would eventually pay for his suspected transgressions.

Whatever his reasons for reoccupying the fort, Hurlbut assured Booth that he would withdraw the garrison as soon as he learned that Forrest was preparing to attack it. In the meantime, Hurlbut advised Booth to keep a sharp eye out for Forrest and his men, who were reportedly already moving into the area. Booth was either extremely confident or extremely careless. Things were quiet for 30 or 40 miles around Fort Pillow, he assured Hurlbut. “I think it is perfectly safe. I can hold the post against any force for forty-eight hours.” Events would soon prove him tragically wrong on both counts.

Forrest Discover’s Fort Pillow’s Weakness

Forrest rendezvoused with Chalmers at Brownsville, 38 miles east of Fort Pillow, on the afternoon of April 11. He directed Chalmers to head for Fort Pillow as early as possible the next morning. Chalmers, well schooled in Forrest’s maxims of speed, obedience, and decisiveness, headed out the next day at 6 am. Colonels Robert McCulloch and Tyree Bell, commanding Chalmers’ two brigades, soon made contact with Federal pickets outside the fort. Captain Frank J. Smith of the 2nd Missouri, leading the Confederate advance, sent his men creeping around behind the pickets to pick them off. Only a handful of pickets managed to make it back to the fort with the unwelcome news that Forrest’s Rebels had suddenly appeared as if out of thin air.

Forrest’s veteran fighters quickly consolidated their position. The Federal defenders, with characteristic laxity, had failed to man the outer works, allowing the Southern troopers to concentrate their fire on the inner line of works. Sharpshooters quickly moved into place behind fallen logs, tree stumps and thick underbrush, and atop high knolls overlooking the fort. They began pouring devastating volleys into the surprised Union ranks, concentrating on the officers. “We suffered pretty severely in the loss of commissioned officers by the unerring aim of the rebel sharpshooters,” Lieutenant Mack J. Leaming of the 13th Tennessee reported later. Among the first to fall was Major Booth, who had been strolling incautiously between the fort’s two battery ports when he was fatally struck by a rifle bullet to the chest. His death, reported at 9 am, abruptly left the fort under the command of the comparatively inexperienced Bradford, who now had the position he had wanted from the first. Doubtless, he would have wished for better timing.

United States Colored Troops (USCT).

Two African American units, the 6th U.S. Heavy Artillery and the 2nd U.S. Light Artillery, were stationed at Fort Pillow.

Forrest arrived on the field an hour later and, as was his wont, immediately undertook a personal reconnaissance of the scene. By this time Chalmers’ men had captured the second line of works and invested the fort itself. Fire from inside the battlements killed two of Forrest’s horses, the second rearing up abruptly and falling backward onto the furious general, badly bruising his leg and doing little to improve his disposition. Forrest’s adjutant, Captain Charles W. Anderson, suggested mildly that the general complete his reconnaissance on foot, but Forrest told him in no uncertain terms that he was “just as apt to be hit one way as another, and that he could see better where he was.” Forrest skulked from no man.

With his experienced eye, it did not take Forrest long to pinpoint Fort Pillow’s fatal flaws. Not only did the numerous ravines provide perfect cover for his men, allowing them to approach as near as 25 yards without detection, but the Union artillery pieces could not be depressed sharply enough to fire at the enemy with any success. Anderson summed up the morning’s findings: “The width or thickness of the works across the top prevented the garrison from firing down on us, as it could only be done by mounting and exposing themselves to the unerring aim of our sharpshooters, posted behind stumps and logs and all the neighboring hills. They were also unable to depress their artillery so as to rake these slopes with grape and canister, and so far as safety was concerned, we were as well fortified as they were; the only difference was that they were on one side and we on the other of the same fortification. They had no sharpshooters with which to annoy our main force, while ours sent a score of bullets at every head that appeared above the walls. It was perfectly apparent to any man endowed with the smallest amount of common sense that to all intents and purposes the fort was ours.” Unfortunately for the defenders, common sense was in short supply that day.

282 Shells From New Era

Bradford, the new commander, apparently believed that he could either hold out until reinforcements arrived in the form of two troop ships steaming up from Memphis, or he could somehow bluff Nathan Bedford Forrest into withdrawing. Bradford had read the misleading newspaper accounts of the Paducah incident; Forrest didn’t read newspapers.

From their concealed vantage points, the Confederates continued to blaze away at the Federals huddling ineffectually behind their breastworks. Meanwhile, McCulloch’s men moved into position among the barracks huts southwest of the fort that the hastily retreating soldiers had failed to set afire. At the northern end of the fort, Colonel Clark R. Barteau’s 2nd Tennessee Regiment moved into place in a deep ravine below Coal Creek. The creek, swollen by heavy rains and backwater from the river, was completely impassable. The fort, with its back to the river, was literally surrounded by water.

With Forrest’s riflemen keeping the defenders pinned down inside the fort, Captain Marshall brought New Era briefly into the fray, her guns sending 282 shells into the Confederate ranks before backing away from the bluff at 1 pm to avoid continuing sniper fire. Few of the shells did any real damage to the attackers—if anything, they merely angered the Southerners even more.

Forrest’s Offer of Surrender to Fort Pillow

Forrest called a temporary halt to the firing while he waited for his ammunition train to catch up to the main body. The wagons, forced to struggle through churned-up dirt roads from Brownsville, finally reached the outskirts of the fort at 3:30. Unaware that Booth was already long dead, Forrest sent a trio of messengers into the fort under a flag of truce. The three, Captains Walker A. Goodman and Thomas Henderson and Lieutenant Frank Rodgers, bore the usual implacable Forrest surrender demand. “The conduct of the officers and men garrisoning Fort Pillow has been such as to entitle them to be treated as prisoners of war,” Forrest wrote. “I demand the unconditional surrender of this garrison, promising that you shall be treated as prisoners of war. My men have received a fresh supply of ammunition, and from their present position can easily assault and capture the fort. Should my demand be refused, I cannot be responsible for the fate of your command.”

Forrest, who had made millions as a slave trader before the war, was always unyielding in his surrender demands. He knew how to bluff and how to bargain. One aspect of the current note surprised Forrest’s own officers. Standard Confederate procedure was to treat former slaves as recovered property, not prisoners of war. There were a number of such former slaves in the two black units at Fort Pillow. Despite dealing from an overwhelming position of strength, Forrest was apparently granting the defenders a significant concession. “There was some discussion about it among the officers present,” noted Goodman, “and it was asked whether it was intended to include the Negro soldiers as well as the white, to which both General Forrest and General Chalmers replied that it was so intended and that if the fort surrendered the whole garrison, white and black, should be treated as prisoners of war.”

Forrest was not typically motivated by excessive feelings of mercy toward the enemy, but he may have wanted to avoid needless casualties to his own troops by unilaterally eliminating the necessity on the part of the African American soldiers to hold out to the last man. If so, his pragmatic charity would fall on deaf ears—specifically Major Bradford’s, which were the only ears that mattered. Later described as “too brave for his own good,” Bradford falsely responded to Forrest’s note under Booth’s name and requested an hour’s time to make his decision.

“I Will Not Surrender”

The usually wily Forrest agreed but immediately regretted his decision when he observed two new Union steamers, Olive Branch and Liberty, hastening upriver toward the fort. The first ship was loaded down with Union soldiers and artillery. Forrest immediately dispatched two squads of riflemen to the bluffs above and below the fort to prevent any enemy reinforcements from landing. “Shoot at everything blue betwixt wind and water,” he ordered. Inexplicably, Captain Marshall, as overall commander of naval forces in the area, told the two boats to pass by without attempting to relieve Fort Pillow, and they proceeded on to Cairo, Illinois, blithely unaware of the fire and brimstone about to descend upon the fort and its beleaguered defenders.

Alarmed and angered by the apparent attempt to land Union reinforcements at Fort Pillow while under a flag of truce, Forrest sent a new message to Booth (actually Bradford) demanding that he make his decision within the next 20 minutes. Bradford conferred with the other officers in camp and sent word to Forrest stating vaguely, “Your demand does not produce the desired result.” Forrest did not have the time or patience for subtle word games. “Send it back, and say to Mayor Booth that I must have an answer in plain English,” Forest said. “Yes or no.” Booth, of course, was beyond answering, but Bradford, still posing as Booth, returned a blunt new reply: “General: I will not surrender. Very respectfully, your obedient servant, L.F. Booth, commanding U.S. forces, Fort Pillow.” To a worried physician trapped inside the fort with the soldiers, Bradford gave a simple reason for his refusal to surrender. “My name is not Hawkins,” he said, alluding to the much-derided surrender by Colonel Isaac Hawkins at Union City two weeks earlier.

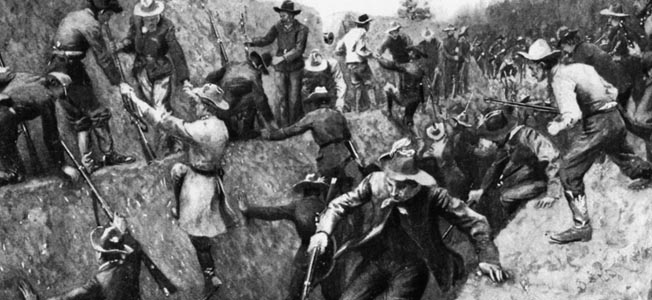

Amazed and annoyed at the response, Forrest wasted no more time in mounting an attack. He signaled bugler Jacob Gaus to sound the charge, then retired to a hill 400 yards away to watch the assault. The bugle notes had scarcely drifted away on the breeze before the Confederate sharpshooters unleashed another devastating blast at the fort’s parapets to cover the attack. The flummoxed defenders were unable to so much as raise their heads above the works for fear they would be shot off their shoulders. Meanwhile, Forrest’s men sprang from concealment in the ravines and behind the barracks huts and tore across the remaining few yards to the ditch surrounding the fort.

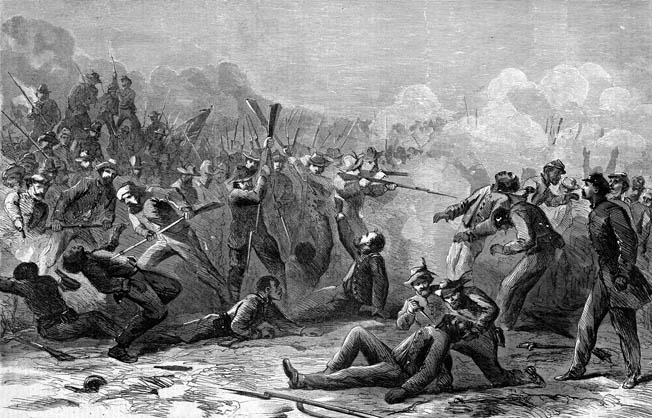

Boiling into the ditch like a swarm of angry hornets, the Confederates began boosting one another onto the outer ledge below the fort’s wall. Lieutenant Leaming, who left behind the only official Union report of the battle, said the attackers seemed to “rise from out of the very earth.” Virtually unopposed, they leaped onto the top of the wall and began blasting away at the cowering Federals, many of whom reportedly were intoxicated after emptying barrels of whiskey that Bradford had ill-advisedly put out prior to the final assault. If he had hoped to strengthen the defenders’ resolve, Bradford had badly miscalculated. Tennessee-born Captain DeWitt Clinton Fort, in the forefront of the attack despite having been born with a club foot, observed the enemy’s reaction. “As we charged over the ramparts,” reported Fort, “the enemy’s garrison of mixed complexion retreated over the bluff down to the water’s edge. Here was assembled one wild promiscuous mass rendered senseless and uncontrollable by the three causes—fright, drunkenness, and desperation.” It was a potent—and ultimately fatal—mix.

“Boys, Save Your Lives!”

The terrified defenders, black and white, broke and ran for the open rear of the fort. One African American artilleryman, Private John Kennedy of the 2nd U.S. Colored Light Artillery, heard Bradford shout, “Boys, save your lives!” No one needed the advice. Kennedy urged Bradford to “let us fight yet,” but the major, seeing Confederate attackers pouring in from all directions, said despairingly, “It is of no use anymore.” The demoralized commander fled to the rear with the majority of his remaining troops.

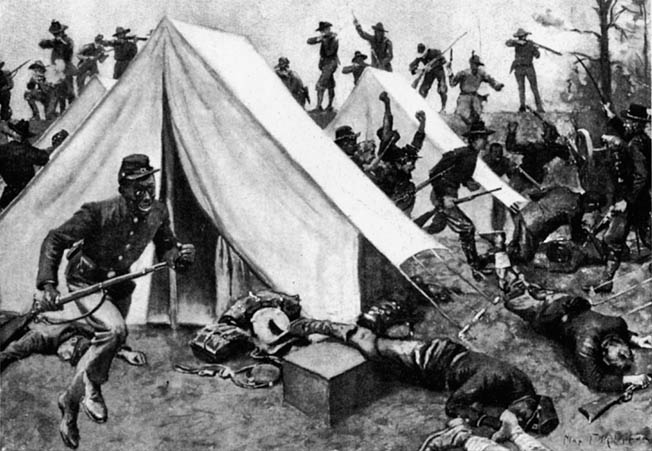

Behind him, the interior of the fort was a scene of mass confusion. Some of the Federals threw down their weapons and attempted to surrender, while others continued firing. Still others simply ran away, spilling over the brow of the bluff and sliding down the vine-choked bank toward the river. Bradford and Marshall had worked out a prearranged signal for New Era to steam closer to the bank at the first sign of trouble and “give the Rebels canister.” But now, in the midst of the developing rout, Marshall unaccountably flinched. To Bradford’s horrified consternation, Marshall swung the gunboat away from the shore and began backing into the middle of the river. (In highly questionable testimony before a congressional committee a few months later, Marshall said weakly that he had abandoned the plan because he was afraid the Confederates “might hail in a steamboat from below, capture her, put on four or five hundred men, and come after me.” Marshall was no one’s idea of John Paul Jones.) Meanwhile, unhampered by return fire, Forrest’s marksmen stationed above and below the fort caught the retreating Federals at point-blank range and enfiladed the frantic fugitives.

Pandemonium reigned inside Fort Pillow. The enraged Confederates, most of whom had ridden all night to the outskirts of the fort, run and sniped under enemy fire all morning, and then waited anxiously in the hot afternoon sun for the final assault to begin, were in no mood to be forgiving. To a man they believed the Federals had been fools for rejecting Forrest’s generous surrender offer. That refusal had cost them another 100 good men, dead or wounded, in the interim. The sight of African American soldiers at the fort was an added insult to the white-supremacist Southerners, who seethed at the racially motivated gibes from some of the defiant, if overconfident, defenders.

Slaughter in Fort Pillow

Many extraneous factors now came to a head. The volatile mixture of racial animosity, long-simmering feuds with white Tennessee Unionists, reports of atrocities committed against their own women and children by those same Unionists, lingering embarrassment over the Paducah raid, physical exhaustion, battle excitement, and fear for their own lives produced a brief but deadly spasm of revenge. Given the prevailing racial politics of the time, the African American soldiers who had so recently been assigned to the fort and who had taken no part in the earlier outrages, now suffered the brunt of the blame.

In the swirling confusion inside the fort, the situation rapidly deteriorated. Before Forrest could mount up and ride into the fort to restore order, an untold number of Union troops were shot down attempting to surrender. Others continued to shoot back, further adding to the chaos. The fort’s Union flag still flew above the ramparts, and Confederates below the bluff had no way of knowing what was going on inside the fort. As Dewitt Clint Fort noted in his diary after the battle, “The wildest confusion prevailed among those who had run down the bluff. Many of them had thrown down their arms while running and seemed desirous to surrender while many others had carried their guns with them and were loading and firing back up the bluff at us with a desperation which seemed worse than senseless. We could only stand there and fire until the last man of them was ready to surrender.”

Other observers, Union and Confederate, told a more lurid tale of the fighting. Fellow Southerner Achilles V. Clark of the 20th Tennessee Cavalry reported in a letter home that “the slaughter was awful. Words cannot describe the scene. The poor deluded Negroes would run up to our men, fall upon their knees and with uplifted hands scream for mercy, but they were ordered to their feet and then shot down. The white men fared little better.” Private George Shaw of the 6th USCHA alleged that he had been wounded after trying to surrender. Shaw said he heard a Confederate soldier shout, as he was raising his rifle, “Damn you, you are fighting against your master!”

Other African American soldiers told similar horrifying stories. Private Benjamin Robinson told government investigators that he saw the Confederates “shoot two white men right by the side of me after they had laid their guns down.” Fellow private Ransom Anderson testified that he was slashed with a bayonet while lying on the ground after surrendering and that he observed another member of B Company, Coolie Rice, “stabbed by a rebel soldier with a bayonet and the bayonet broken off in his body.” White Union cavalryman Daniel Stamps later testified that “while I was standing at the bottom of the hill, I heard a rebel officer shout out an order of some kind to the men who had taken us, and saw a Rebel soldier standing by me. I asked him what the officer had said. It was ‘kill the last damn one of them.’ The soldier replied to his officer that we had surrendered, that we were prisoners and must not be shot. The officer again replied, seeming crazy with rage that he had not been obeyed, ‘I tell you to kill the last God damned one of them.’”

Whoever—if anyone—had issued such an order, it was apparently not Forrest. Chalmers told a captured Union officer the next day that he and Forrest had “stopped the massacre as soon as we were able to do so.” Another Confederate at the scene, Surgeon Samuel H. Caldwell of the 16th Tennessee Cavalry, wrote to his wife on April 15, “If General Forrest had not run between our men & the Yanks with his pistol and sabre drawn not a man would have been spared.” Brigade commander Colonel Tyree Bell blamed what he called “promiscuous firing” by Forrest’s men on the drunken, panicky behavior of the enemy. “The drunken condition of the garrison and the failure of Colonel Bradford to surrender, thus necessitating the assault, were the causes of the fatality,” Bell told Forrest biographer John A. Wyeth 35 years later.

Killing Captain Bradford

Within half an hour the battle was over. Of the fort’s total garrison of 580 men, some 354 apparently were killed or wounded. Final figures are still hotly disputed. Of these, a large number drowned while attempting to swim out to the Union vessels that were steaming away without them. Another 226 were taken prisoner, including Bradford, who emerged from the river dripping and shivering and was taken to Colonel McCulloch’s tent for safety. McCulloch allowed Bradford to temporarily leave his custody to superintend the burial of his brother, Captain Theodorick Bradford, who had been killed at Fort Pillow. Instead of returning to camp, Bradford attempted to escape only to be recaptured wearing civilian clothes near Covington, Tennessee. Two days later he was taken into the woods near Brownsville and shot by his guards. “A great many of the soldiers in Forrest’s command felt that they had a personal grievance against this man,” Forrest biographer Wyeth observed somewhat mildly. “It was not a matter of great surprise that opportunity was taken to exact private revenge upon him at this time.” The fact that Bradford was captured in civilian disguise gave at least a patina of legality to his execution.

“Remember Fort Pillow!”

Almost immediately, word spread across both the North and the South that Forrest and his men had conducted a virtual massacre at the fort. Forrest’s exultant first report, three days after the battle, encouraged such a reading. “The victory was complete,” he announced. “The river was dyed with the blood of the slaughtered for 200 yards. It is hoped that these facts will demonstrate to the Northern people that Negro soldiers cannot cope with Southerners.” Chalmers echoed those sentiments. The Confederate victory at Fort Pillow, he said, “had taught the mongrel garrison of blacks and renegades a lesson long to be remembered.”

Within a week, the Federal government mounted a well-publicized investigation into the “massacre” at Fort Pillow. A special subcommittee of the U.S. Congress’s Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War hurried to Tennessee to take—and sometimes invent—eyewitness accounts of the battle and its aftermath. The committee, chaired by radical Republican Senator Benjamin F. Wade of Ohio, issued a highly charged report accusing Forrest and his men of engaging in “an indiscriminate slaughter, sparing neither age or sex, white or black, soldier or civilian.” The fact that no women or children were killed at the fort and only one civilian (who had taken up arms at the time of the attack), did not deter Wade’s committee from releasing its findings as fact. The partisan report was useless as an evidentiary document, but it was inarguable that the vast majority of Union soldiers killed at Fort Pillow, either during or immediately after the battle, were black. Of the 262 African American soldiers at the fort, only 58—or 22 percent—were taken away as prisoners, as opposed to 168 white prisoners, nearly three times as many.

Forrest himself, in a little known postwar interview with fellow Confederate general Dabney H. Maury in the Philadelphia Weekly Times, went to some pains to mitigate his role in the battle. “When we got into the fort the white flag was shown at once,” Forrest said. “The Negroes ran out down to the river, and although the white flag was flying, they kept on turning back and shooting at my men, who consequently continued to fire into them crowded on the brink of the river, and they killed a good many of them in spite of my efforts, and those of their officers to stop them. But there was no deliberate intention nor effort to massacre the garrison as has been so generally reported by the Northern papers.”

Deliberate or not, the casualty figures at Fort Pillow would linger over Forrest for the remainder of the war, even after William Tecumseh Sherman—surely no Confederate apologist—determined that there was no cause for further investigation or retaliation. “Let the soldiers affected make their own rules as we progress,” Sherman told Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton. “We will use their own logic against the enemy as we have from the beginning of the war.” Subsequently, the battle cry “Remember Fort Pillow!” would rise from Union soldiers’ lips for the remainder of the war. In many ways, it is still echoing today.

This was so informative and describes the battle story from each side right or wrong, thank you.

There has been a certain amount of revisionism regarding Forrest’s actions or lack thereof lately. While it is disputed that Forrest directly ordered reprisals against Black Union soldiers at Ft. Pillow, the concept of command responsibility has followed him throughout history. The fact that an inquiry later determined that a massacre did take place, held Forrest and the Confederates responsible and has remained since. The allegation that Forrest was the inspiration behind the founding of the KKK further reinforced his negative reputation.