After his exploratory expedition to the Shenandoah Valley in 1716, Virginia Governor Alexander Spotswood encouraged Germans and Dutch farmers residing in eastern Pennsylvania to settle the region when he found Virginians in the Tidewater and Piedmont regions of his state initially reluctant to settle beyond the Blue Ridge Mountains.

Quakers from Pennsylvania settled in what became Winchester, and German and Dutch homesteaders founded New Mecklenburg and Staufferstadt, which were later renamed Shepherdstown and Strasburg, respectively. This in turn triggered the movement of Scotch-Irish settlers into the southern end of the Valley to found Harrisonburg, Staunton, and other towns. By the time of the Civil War the Valley boasted hundreds of farms and more than a dozen thriving market towns.

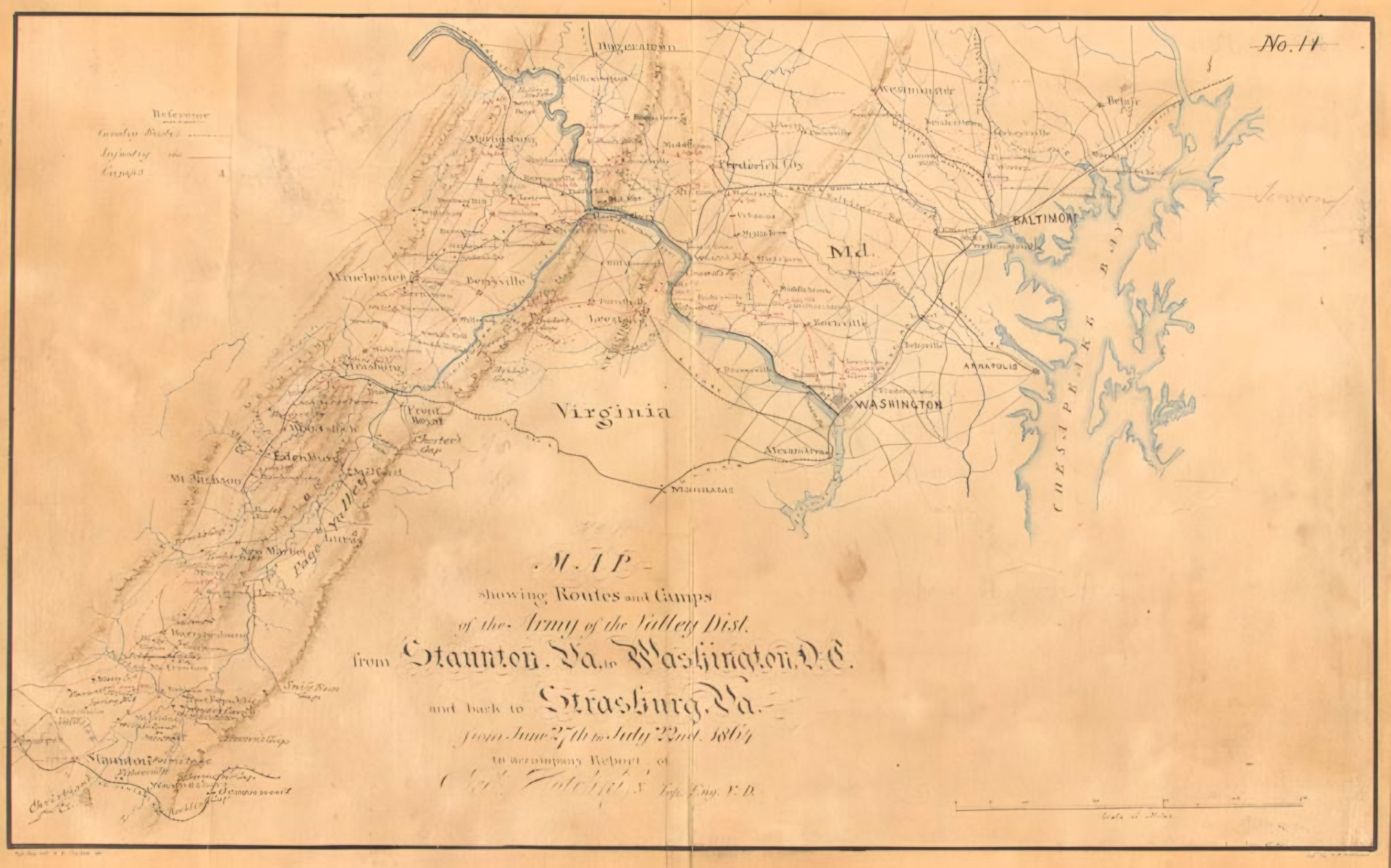

Understanding the region’s topography was essential to the success of both Confederate and Union armies during the Civil War. The Shenandoah Valley is a 150-mile-long corridor that ranges in width from 20 to 35 miles. The Valley is enclosed on the west side by the towering Alleghany Mountains and on the east side by the Blue Ridge Mountains. Nine wind gaps afforded access to the Valley from Virginia’s Piedmont Region.

Four miles east of Strasburg is the northern end of the 2,900-foot-high Massanutten Mountain that runs through the middle of the Valley and separates the north and south forks of the Shenandoah River. Because the Shenandoah River flows north, local residents called the northern half of the Shenandoah Valley the “Lower Valley,” because it was downstream, and the southern half the “Upper Valley” because it was upstream.

Valley farmers grew wheat, corn, rye, barley, oats, and potatoes and raised livestock in the deep, fertile soil. Since the region produced nearly 20 percent of Antebellum Virginia’s annual wheat crop, it became known as the “Breadbasket of the Confederacy.”

The Virginia General Assembly chartered the Valley Pike, a 93-mile macadamized road of pulverized limestone, in 1834 that ran from Winchester to Staunton. It enabled Confederate forces operating in the Valley to rapidly move supply wagons and gun carriages up and down the Valley. By the time of the Civil War, the Valley had several railroads, but they were not connected with each other.

Having received his second star in October 1861 for his role in the Confederate victory at First Manassas, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson returned to the Shenandoah Valley and established his headquarters in Winchester at the home of Lt. Col. Lewis Moore of the 4th Virginia the following month. As commander of the Valley District, he initially had just 4,540 troops and 20 artillery pieces. Intelligence reports indicated that 40,000 Federals stood prepared to invade the Lower Valley.

When his friend Alexander Boteler of Shepherdstown, a member of the Confederate Provisional Congress, paid him a visit in November, Jackson implored him to advise Confederate authorities in Richmond that it was imperative that the general receive reinforcements to defend the strategically important region. “If the Valley is lost, Virginia is lost,” Jackson told him.

In addition to needing more troops, Jackson wanted a better understanding of the topography of the Shenandoah Valley and its road network. He tasked school teacher Jedediah Hotchkiss of Augusta County, a self-taught cartographer, to draw a detailed map of the Shenandoah Valley for use in the anticipated campaign against the Federals.

“I want you to make me a map of the Valley from Harpers Ferry to Lexington, showing all of the points of offense and defense between these points,” Jackson said. The maps served him well in spring 1862 and enabled Jackson to march with great speed and stealth against the Union forces arrayed against him.

—William E. Welsh

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments