By Patrick J. Chaisson

It was an amphibious commander’s worst nightmare—swarms of enemy tanks, spitting death with every cannon shell and machine-gun burst, smashing through the American beachhead. Stunned GIs were crushed in their foxholes by the unstoppable leviathans, or bayoneted by accompanying infantry. The few Allied fighting vehicles then on shore stood no chance against this mechanized onslaught. By dawn, after destroying ammunition dumps, supply depots, and motor pools, the Japanese attackers finally halted. Victorious, they had hurled their foe back into the sea.

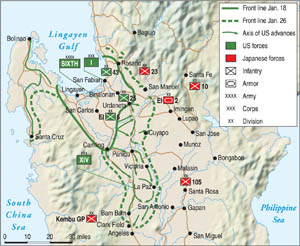

For Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, the threat of just such an armored counterthrust, an imagined nightmare scenario, made for many anxious moments. In January 1945, this U.S. Army officer found himself part of a landing force preparing to invade Luzon, the largest of the Philippine Islands. Swift’s task as commanding general of I Corps was a straightforward one: cover the flank of Lt. Gen. Walter Krueger’s Sixth Army as it liberated the capital city of Manila, thus fulfilling General Douglas MacArthur’s vow to the Filipino people.

Much like MacArthur, “Bull” Swift was also returning to the Philippines. He had been there before, as an aide to General John J. Pershing in 1908. Swift later patrolled the Mexican border alongside George S. Patton, Jr., before heading overseas with the 86th Division during World War I. Entering battle again in 1944 as commander of the First Cavalry Division, he earned rare praise from MacArthur for his efficient work throughout the Admiralty Islands campaign.

In charge of I Corps since August 1944, this ramrod-straight cavalryman had been serving his nation as a soldier for more than 40 years. He was, at age 62, the oldest and most experienced corps commander in the U.S. Army. As such, Innis Swift could be trusted to carry out the toughest assignments in MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Theater of Operations.

There was nothing glamorous about the job awaiting I Corps on Luzon. Swift’s 60,000 troops were to come ashore near San Fabian and fan out rapidly along a line extending 15 miles north and east of the Lingayen beachheads. The I Corps front controlled access to Luzon’s Central Plains, a large, mostly wide-open avenue of approach that led 135 road miles to Manila. This ground had to be secured before the men of Maj. Gen. Oscar W. Griswold’s XIV Corps could make their “glory-ride” on the capital of the Philippines. Afterward, I Corps would pivot toward the rugged Sierra Madre mountain range of northern Luzon and mop up any Japanese still holding out there.

But a very dangerous man stood in the way of Bull Swift’s plans.

General Tomoyuki Yamashita, age 59, was the Imperial Japanese Army’s canniest tactician—a man nicknamed the “Tiger of Malaya” for his stunning conquest of British-held Singapore in 1942. Now, three years later, Yamashita commanded some 262,000 combatants of the 14th Area Army in an assignment most considered utterly impossible. Conventional military wisdom dictated that Luzon was too large and the Allied invaders too powerful for any defensive campaign to possibly succeed.

Yet Yamashita reckoned the more Americans he could tie down in the Philippines, the fewer men MacArthur would have available for an assault on Japan proper. By utilizing the forbidding terrain of northern Luzon together with the warrior spirit of his troops, the Tiger of Malaya hoped to upset Allied strategic timetables for months or even years.

After taking command of the Philippine Islands in October 1944, Yamashita made several controversial decisions. First, he chose to leave Manila unguarded, as that city possessed little strategic value. Japanese Navy forces not under his command would later wreak terrible carnage there. He further forbade ground commanders from entering combat whenever or wherever conditions favored the Allies in naval, air, and mechanized firepower. Henceforth, no effort would be made to defeat amphibious landings on the beaches, nor were the Central Plains to be occupied.

Instead, Yamashita established his main defensive zone along the Caraballo Mountains north and east of Lingayen Bay. For months, Japanese soldiers had been building elaborate bunker systems, stockpiling munitions, and camouflaging artillery positions in this region. Their front line stretched in a 50-mile arc from Rosario in the north down to the vital railhead of San Jose. It was here that supplies from depots in Manila were unloaded and then transported by truck into 14th Area Army’s mountain redoubts.

Until those warehouses could be emptied, however, San Jose needed to remain in Japanese hands. This crossroads barrio (village) also protected the entrance to Balete Pass, a major route through the Caraballos that led to Yamashita’s headquarters near Baguio. To further complicate matters, in mid-January a division of infantry was slowly marching north through the area to join the 14th Area Army; these riflemen required protection from marauding American armor.

The defense of San Jose would require a thorough yet unconventional plan. The Tiger of Malaya thrived on such problems, though, and on January 11, the 14th Area Army ordered into action its most mobile, battle ready unit. The 2nd Tank Division set out that very night, its destination a triangular sector safeguarding the approaches to San Jose and that town’s vital transportation hub. Under cover of darkness, miles-long tactical columns of armored fighting vehicles, tractor-towed field guns, and truck-mounted mobile infantry began making their way along Luzon’s dust-clogged roadways.

The selection of the 2nd Tank Division to conduct what was essentially a strongpoint defense violated all conventional tactical doctrine but acknowledged both the realities of combat on Luzon as well as the 14th Area Army commander’s unfamiliarity with armor. Said one Japanese officer, “General Yamashita, being an old time infantry soldier, did not believe in mechanized warfare.” Rather, he directed the unit to dig in on key terrain—in effect transforming its tanks into pillboxes.

While this scheme forfeited the principles of maneuver and mass used with great success by other combatant nations’ armored formations, it did offer some benefits. Well-camouflaged battle positions proved all but undetectable by aerial reconnaissance, while tanks fighting behind earthen fortifications were less vulnerable to Allied antiarmor weapons. Lastly, shortages of spare parts, ammunition, and especially diesel fuel meant a static defense was the only realistic course of action left open to Yamashita’s tankers.

Code named Geki (“Attack”) Force, the 2nd Tank Division represented an extraordinarily lethal presence on the battlefield. Under the command of Lt. Gen. Yoshiharu Iwanaka, it had available in January 1945 approximately 11,200 men and 1,500 vehicles of various types. Despite suffering losses to American submarine activity during its 1944 deployment from Manchuria to Luzon, Geki Division largely remained intact well into the new year. Some small tank and infantry detachments were sent to reinforce the defenses on Leyte that previous autumn.

The Third Tank Brigade, commanded by Maj. Gen. Isao Shigemi, was Geki Force’s primary maneuver echelon. This formation, which contained the 6th, 7th, and 10th Tank Regiments, normally operated with the 2nd Mobile Infantry Regiment. In early January, though, two battalions of those truck-mounted riflemen were detached to defend other positions in the south. Partly to make up for the 2nd Tank Division’s shortfalls in foot soldiers, Yamashita forwarded several hundred personnel of the 26th Independent Mixed Regiment and the 356th Independent Infantry Battalion to help hold San Jose.

Fire support was provided by 105mm and 150mm field pieces of the 2nd Mobile Artillery Regiment. Other combat elements included one company each of antitank (AT) guns and combat engineers. Logistical sustainment groups consisted of a maintenance company and transportation section; motorized signal and medical detachments completed the division’s organizational structure.

The 2nd Tank Division’s primary weapon system on Luzon was the Type 97-kai Shinhoto Chi-Ha medium tank, some 175 of which were assigned. Weighing 17.4 tons combat loaded and powered by a 170-horsepower V-12 diesel engine, the Type 97 could achieve road speeds of 24 miles per hour. Geki Force’s tanks came equipped with a high-velocity 47mm cannon and 7.7mm machine gun in the turret, as well as one hull-mounted machine gun. It took five men (gunner, tank commander, loader, driver, and hull gunner) to crew a Shinhoto Chi-Ha.

On hand as well were about 20 light tanks designated the Type 95 Ha-Go. Used primarily as a command vehicle on Luzon, this nimble cruiser tipped the scales at eight tons. Its Mitsubishi V-6 engine, rated at 120-horsepower, drove the Type 95 to a top speed of 28 miles per hour. Armament included a 37mm cannon and two 7.7mm machine guns. Each Ha-Go was crewed by three men: a driver, hull gunner, and tank commander, who also operated the turret weapons.

The 2nd Tank Division also fielded several experimental turretless tank destroyers as well as specialized engineer vehicles and self-propelled howitzers. Mechanics even got into the operation of a few antique tanks—Japanese and American—left over from the 1942 invasion. Anything with tracks, it seemed, was pressed into service by Iwanaka’s troopers.

Tank for tank, Geki Force’s armored fighting vehicles were no match for the M4 Shermans operated by I Corps. The Shinhoto Chi-Ha’s 47mm AT projectile could only penetrate an M4’s side or rear at close range, while U.S. 75mm shells punched right through Japanese steel plate at any distance or angle. The Shermans coming ashore on Luzon enjoyed every tactical advantage—mobility, firepower, and armor protection—except one. Against Iwanaka’s 220 tanks Swift could muster a mere 59 M4s.

Actually, the U.S. Army possessed more than 500 armored vehicles in the Philippines, but senior commanders held most of them back lest the 2nd Tank Division suddenly appear as the vanguard of a massive counteroffensive. American intelligence officers did not yet know that the Japanese had instead dug in their tanks to protect the transportation network at San Jose. The job of finding and then destroying Geki Force would have to be performed by the riflemen of Bull Swift’s 6th, 25th, and 43rd Infantry Divisions.

While the soldiers of all three divisions were battle tested, their experiences thus far had been in the rainforests of New Guinea or the Solomon Islands. Captain Michael Kane, a rifle company commander in the 20th Infantry Regiment, 6th Infantry Division, remembered his men needed to “unlearn” these jungle fighting skills before “relearning” more conventional, open terrain tactics. Kane added that his troops familiarized themselves with such antiarmor weapons as the “bazooka” rocket launcher and rifle grenade before sailing to Luzon.

Also training hard were gunners of the U.S. infantry’s AT platoons, who thus far had rarely used their towed 37mm cannons against Japanese armor. Destined too for tank-killing duty were the six 105mm M7 self-propelled howitzers in each infantry regiment’s Cannon Company. Though designed for use as an artillery carriage, these lightly armored vehicles would soon be advancing alongside U.S. riflemen as direct-fire assault guns.

Several attached units augmented I Corps’ infantry strength. The veteran 98th Chemical Mortar (CM) Battalion could rapidly drop sheaves of 4.2-inch high-explosive and white phosphorus rounds, suppressing or even eliminating fortified targets. Finally, spread across the corps were 59 M4 Sherman and 17 M5A1 Stuart tanks of the 716th Tank Battalion (TB). Their mission was to provide infantry support, although most tank gunners secretly itched to see a Type 97 in their sights. Many of them would get this opportunity before long.

The first waves of GIs to come ashore on January 9, 1945 (“S-Day” to Allied planners), quickly overran Lingayen Bay’s beachheads. As these assault echelons surged inland, however, Maj. Gen. Swift and his subordinate commanders grew increasingly concerned over the whereabouts of the 2nd Tank Division. The Americans had never faced such a large concentration of Japanese armor, and the threat of this potent force turning up behind U.S. lines continued to worry I Corps’ officers. Aerial reconnaissance overflights furnished few clues, and reports from friendly Filipinos often proved unreliable.

Patrols from the 43rd Infantry Division discovered their foe’s main defensive belt on January 11 while advancing up the coast near Rosario. There, along a ridgeline eight miles north of the Lingayen beaches, American attackers collided with Yamashita’s well-concealed riflemen. All attempts to turn the Japanese lines were met by an avalanche of artillery and small-arms fire. The I Corps’ rapid advance had ground to a halt.

In the meantime, Geki Force was completing its move into the San Jose region. Lt. Gen. Iwanaka established his command post, along with the division’s logistics trains and a small headquarters guard, two miles north of town. Five miles farther on, the 10th Tank Regiment entrenched at Lupao. In a barrio named Muñoz, nine miles southwest of San Jose, the 6th Tank Regiment began constructing strong earthworks. Small outposts stationed to the west provided early warning of advancing Allied units.

Geki Force anchored its northern flank at San Manuel, a village located alongside the Agno River about 40 miles northwest of San Jose. There Maj. Gen. Shigemi determined to make his final stand. “We will hold present positions to the death!” he declared in mid-January, dramatically concluding, “The enemy must be annihilated!”

While the Japanese were committed to a strongpoint defense of San Manuel, Lupao, and Muñoz, Yamashita did authorize several limited counterattacks intended to disrupt the U.S. offensive. One such probe, which took place over the night of January 14 near a settlement named Malasin, marked the first contact between the 2nd Tank Division and I Corps. During this brief fight, three light tanks blundered into a roadblock set up by Company A, 103rd Infantry Regiment, 43rd Infantry Division. One Ha-Go was taken out by bazooka fire, prompting the others to turn around and flee.

The Japanese struck again on January 16-17 when a combined armor/infantry team under the command of 1st Lt. Yoshitaka Takaki set out from its base at Binalonan on a nighttime raid. They got as far as Potpot, a tiny hamlet defended by the same Company A, 103rd Infantry that first encountered Geki Division at Malasin.

Two of Takaki’s lead tanks caught the Americans completely by surprise around midnight. With machine guns blazing, they drove straight through Company A’s perimeter before racing off into the gloom. AT gunners knocked out a third vehicle but then got caught up in a tenacious attack that lasted for more than two hours. At one point a platoon of Shermans from Company C, 716th TB went forward to help contain this menace.

The fighting ended at dawn when those two rogue vehicles that had earlier sped past U.S. lines clattered back up the road to Potpot, only to be stopped by now-alert gun crews. American casualties were light, two GIs killed and 10 wounded, while Takaki’s losses amounted to 11 tanks destroyed or damaged plus some 50 infantrymen fallen.

Even as the shooting stopped in Potpot, a new player was entering the game. Troops of the 25th “Tropic Lightning” Division stepped in on January 17 to fill a widening gap between I Corps’ 43rd Infantry Division to the north and the 6th Infantry then pressing southward. Backed by Company C, 716th TB, the 25th immediately started moving on San Manuel. Leading off was the 161st Infantry Regiment, veterans of fierce combat on Guadalcanal and the northern Solomon Islands.

Before they could capture San Manuel, however, the 161st‘s soldiers needed to neutralize a combat outpost at Binalonan. Later that afternoon, the 3rd Battalion entered the northern part of town where at 1730 hours they dispatched a single prowling Shinhoto Chi-Ha. Five more tanks then charged down the street, spewing machine-gun fire in all directions before bazooka teams and AT grenadiers could stop them. By nightfall, American riflemen had established a firm foothold in Binalonan.

The next morning 3/161st Infantry, aided by three M4s of Company C, succeeded in capturing this crossroads village. While some personnel and vehicles managed to slip away, the Japanese casualty count at Binalonan added up to nine tanks, two 75mm field guns, five trucks, one artillery tractor, and 250 combatants. U.S. losses included 19 men killed and another 66 wounded.

Not every battle fought against Geki Force ended in such a lopsided victory for the Americans. On the same day that U.S. patrols entered Binalonan, a column of Shermans cautiously approached the community of Urdaneta, 61/2milesto the south. Led by Lt. Robert Courtwright of Company A, 716th TB, this three-tank section was screening the advance of 6th Infantry Division foot soldiers.

Lying in wait for Courtwright’s M4s was Warrant Officer Kojura Wada. His three Type 97 tanks sat just off the road concealed in a mango grove and were perfectly positioned to ambush the Americans. Wada later recalled this tense moment: “I heard faint track noises…. One, two, three enemy tanks appeared among the palm trees; the white star painted on the front of each tank was clearly visible. They were 100 meters away—70 meters—50 meters—30 meters—but [still] they did not notice our tanks, because we were well-camouflaged.”

At a range of 25 yards, the Japanese opened fire. “Driver Yamashita shouted ‘Hit!’” Wada related. “The leading tank caught fire and turned to the opposite side of the road…. The second enemy tank also caught on fire after several hits.” Wada estimated his gunner put 60 47mm AT rounds into the third Sherman, which although disabled was able to return fire—knocking all three Shinhoto Chi-Has out of action.

In this engagement Courtwright suffered two tankers dead and two wounded. One of his M4s was declared a total loss, while the other two eventually returned to service. Sixth Infantry Division troops seized Urdaneta later that day, destroying nine Japanese tanks and killing 100 riflemen. The 2nd Tank Division’s outpost line had been smashed; could its bastions in San Manuel, Lupao, and Muñoz hold out long enough for those supplies and redeploying infantry to pass through San Jose?

The barrio of San Manuel sat between Highway 3, a major north-south thoroughfare, and the Agno River. While the surrounding countryside was mostly flat, an 850-foot-tall ridgeline one mile to the north provided excellent observation. The Villa Verde Trail, a footpath winding through the Caraballo Mountains, served as the garrison’s sole route of escape.

Occupying this village were at least 1,000 soldiers, plus 45 Type 97s and Type 95s of Shigemi’s 7th Tank Regiment. To protect their vehicles, Shigemi’s crews constructed sturdy adobe revetments that were then carefully concealed. Alternate fighting positions—75 of them—allowed for a semi-mobile operation in which armor could move back and forth as necessary to defend in depth. Street intersections and choke points were covered by indirect fire, while well-concealed riflemen and AT gunners shielded against enemy assaults. The Japanese then burrowed deep and waited, sworn by their commander to hold San Manuel at all costs.

On January 19, a mixed group of Filipino guerrillas, riflemen from the 161st Infantry, and M5A1 Stuart light tanks belonging to Company D, 716th TB set out to scout the area. Shigemi’s gunners let them get close before opening up, destroying two M5A1s and killing or wounding everyone on board. The Americans then fell back, electing to “soften” their objective with a five-day bombardment. Several battalions of field artillery, working with naval aviation and light bombers from the U.S. Fifth Air Force, flattened San Manuel while ground troops moved in to completely surround the township.

First, that bare ridge to the north was captured so forward observers could use it to call fire down on Japanese emplacements. Next, at 0725 hours on January 24, the 161st Infantry attacked. Advancing southward was 2nd Battalion with the main effort. A supporting assault conducted by 1/161st Infantry and Company C, 716th TB swept up along the Binalonan Road to strike San Manuel from the west.

Both attempts stalled in a hail of small-arms, mortar, and tank fire. Within minutes Company C lost six Shermans, while the 1st Battalion took more than 60 casualties. An unexpected counterthrust by three of Shigemi’s tanks pushed 2nd Battalion out of San Manuel later that morning.

The 161st tried again at 1700 hours. Backed by fast-firing 4.2-inch mortars assigned to Company D, 98th CM Battalion and the M7 howitzers of Cannon Company, 2nd Battalion succeeded in grabbing a toehold on the edge of town. One M7 was wrecked in a suicide attack, but by sundown the GIs had killed five Japanese tanks and were inside San Manuel to stay.

This small victory came at great cost. Technician 4th Grade Laverne Parrish, a medic assigned to 1/161st Infantry, carried to safety five men at San Manuel before he was fatally wounded by mortar fragments on the morning of January 24. For these acts of valor, together with other heroic deeds performed earlier at Binalonan, Parrish received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

For the next two days, U.S. infantry, M7 assault guns, and M4 tanks fought street to street against Shigemi’s detachment. No longer able to withstand the Americans’ relentless attacks, his last remaining soldiers staged a breakout around 0100 hours on January 28. Leading the way were 13 Type 97s. The 161st Infantry’s regimental history tells what happened next:

“The tanks assaulted in waves of three, each tank followed closely by foot troops…. Riflemen in pits opposed them with rifle AT grenades, bazookas and caliber .50 machine guns. Two 37mm guns had the tanks within range. The first tank was hit but overran the forward position, spraying blindly with machine guns and firing 47mm point-blank.

“Ten of the tanks were halted,” concluded the American account, “the leading one just 50 yards inside our front. All had been hit several times. Hits and penetrations were made with AT shells, AT grenades, bazookas and caliber .50 machine guns.”

Perhaps 400 survivors somehow made it out, fleeing northward into the mountains. Shigemi was not among this number, though, having committed ritual suicide earlier that morning. U.S. commanders declared San Manuel secure after four days of intense combat; their casualties numbered 60 dead and 200 wounded. More than 775 Japanese died in the struggle.

With San Manuel firmly in American hands, Swift could turn his attention toward San Jose. On January 30, he ordered the 25th and 6th Infantry Divisions to conduct a pincer-like maneuver designed to cut the major roads leading in and out of this key transportation center.

Speed was paramount; Swift wanted to seize the foe’s routes of retreat before Geki Force slipped through his grasp. At Pemienta U.S. forces succeeded, ambushing a road column of eight Shinhoto Chi-Ha tanks, another eight artillery tractors, and 125 men. They were less fortunate at Umingan, where on January 31, an attack by the Tropic Lightning Division’s 27th Infantry Regiment bogged down in the face of withering automatic weapons fire.

Its forward progress stymied, the 27th held fast while on February 1 an adjacent unit, the 35th Infantry, bypassed Umingan for the nearby barrio of Lupao. Intelligence reports said a company of Japanese riflemen occupied Lupao; in reality, at least 40 tanks plus AT guns and engineers fighting as infantry were dug in there.

First Battalion went in on the afternoon of February 2. Caught in a murderous crossfire, the assault got nowhere. Next, field artillery and 4.2-inch mortars plastered the town with highexplosive and white phosphorous rounds. Another attempt made the next day also failed. Taking Lupao was going to be harder than first thought.

Fighting grew more intense on February 3, when the 3rd Battalion joined the battle. Much like its sister regiment at San Manuel, the 35th Infantry here employed M7 self-propelled howitzers as assault guns to good effect. Their 105mm cannons made short work of Japanese emplacements, enabling American infantrymen to take the southern tip of Lupao.

Once inside the village, advancing GIs played a savage game of cat and mouse with Lupao’s defenders. Bazooka rockets and AT grenades took their toll on dug-in tanks, while snipers and machine guns hidden in the rubble dropped attacking riflemen by the score. A series of ferocious Japanese counterstrikes kept the 35th Infantry off balance, preventing it from pushing through the objective.

A fresh battalion, the 2nd, took over starting February 5. Together with Cannon Company’s ubiquitous M7 assault guns and a detachment of Shermans, the 35th gradually squeezed shut their enemy’s perimeter. On February 7, some riflemen from Company G were moving forward when Japanese gunfire ripped through their ranks. Several soldiers fell while the rest took shelter in a roadside ditch. Though wounded himself, Master Sgt. Charles L. McGaha crawled out on three occasions to retrieve injured men. For this feat, McGaha would receive the Medal of Honor.

That night the Lupao garrison’s last eight tanks tried to bolt. Bazooka fire knocked out three; the rest were later found abandoned. By 1130 hours on February 8, it was all over. In this week-long battle the 35th Infantry Regiment lost 96 killed and 268 wounded, while Japanese casualties exceeded 900 men. Thirty-three demolished tanks were counted in and around the barrio.

While the 35th Infantry was busy clearing Lupao, other I Corps columns maneuvered on San Jose to the south. In the 6th Infantry Division’s zone, patrols from the 20th Infantry Regiment encountered a robust Japanese force defending Muñoz on January 31. This strongpoint was in fact larger than the one up the road at Lupao and would also require a week of hard fighting before the enemy was defeated.

Joining the 20th Infantry for this battle were several battalions of reinforcing field artillery plus two platoons of 4.2-inch mortars belonging to Company A, 98th CM Battalion. Company C, 44th TB also rolled up from corps reserve once it became clear there would be no armored counterblow on Luzon. These newly arrived tankers surveyed their objective with trepidation, as the battalion history related: “Tank operations were limited by the terrain, boggy ground and deep water-filled irrigation ditches. The town of Muñoz was fortified with antitank guns, 105[mm] artillery pieces and 57 light and medium tanks, all of which were dug in and with a three-foot thick top of logs and sandbags over them. In addition, numerous alternate positions were available so the tanks that were in one place one day would be in an alternate position the next.”

The battle for Muñoz began on February 1 when 3/20th Infantry assaulted from the southwest. Little headway was made against heavy resistance, so the next morning 1st Battalion joined the attack. Despite the welcome firepower of M4 tanks and M7 howitzers, the Americans could not advance more than a few yards at a time. The battle settled into a siege on February 4; powerful artillery and mortar barrages kept the Japanese pinned down while American riflemen carefully worked their way forward.

Captain Michael Kane, commanding Company B, 20th Infantry, vividly described one small-unit action that occurred on February 5: “Company B located a tank 75 yards to their front. Immediately they requested one of our supporting tanks to engage the enemy tank. Our tank came up to within ten yards of the Storage Building and, after the crew had been oriented as to the location of the enemy tank, they fired a 75mm round at the Jap[anese] tank, hitting and destroying it. However our tank, before it could withdraw, was hit by a 47mm shell from a mutual[ly] supporting tank…. Our tank burst into flames but the crew escaped safely.”

Technical Sergeant Donald E. Rudolph, an acting platoon leader, became a one-man army that same day when he advanced down a line of eight pillboxes, tossing hand grenades through their firing slits to eliminate the gunners inside. Later, he hopped aboard a Japanese tank that was firing on his troops to drop a white phosphorous grenade down its turret hatch. Rudolph received both the Medal of Honor and a battlefield promotion to second lieutenant for these acts of bravery.

Even though the entire 20th Infantry Regiment was now in action, by February 6 less than half of Muñoz had been brought under U.S. control. It was decided that evening to pull back and let seven battalions of 105mm, 155mm, and 8-inch artillery pulverize the place in an all-night bombardment. Fifth Air Force fighters also prepared to conduct a napalm strike the following morning.

Unknown to the Americans, on February 4 Yamashita ordered Geki Division to pull out of this sector. Due to communications problems, this directive did not reach Iwanaka’s headquarters until two days later. Nevertheless, under cover of a diversionary attack the remnants of Muñoz’s garrison withdrew toward San Jose before sunup on February 7.

They could not know that the 6th Infantry Division had taken San Jose days earlier. Furthermore, the highway leading there was now barricaded by U.S. infantry, artillery, and tanks. Roadblocks set up by the 63rd Infantry Regiment surprised the Japanese column’s lead elements, while nearby a group of tankers from Company C, 44th TB were awakened by the sound of unfamiliar vehicle engines.

“It sounded like an American Caterpillar going full speed,” Company C’s battle report later detailed. “As the vehicle sped by, they recognized it to be a Japanese medium tank. Immediately the alert was sounded and everyone was up.” More enemy armor then approached, shooting wildly into the night.

Another witness chronicled this chaotic encounter: “Japanese tanks pulled into firing position farther up the road, and started shelling the entire Company C area. Although their fire was far from ineffective, one by one they were picked off as the American tankers lined their sights in on the enemy’s lurid muzzle blasts. Some gunners searched for targets by spraying machine-gun tracer bullets in a wide arc. When one struck a Jap[anese] tank, it would spark as it ricocheted off. The vehicle would then be destroyed by 75[mm] cannon fire.”

Sunrise revealed a gruesome scene. Practically the entire garrison of Muñoz—an estimated 2,000 men—perished in this six-day fight. A physical count of wrecked Japanese equipment totaled 48 medium and four light tanks along with 16 AT guns, four armored cars, and four 105mm howitzers. U.S. casualties amounted to 97 dead and 303 wounded.

The 2nd Tank Division had been annihilated. While it held the approaches to San Jose long enough for badly needed supplies and infantry reinforcements to make their way north, the price paid was staggering. In three weeks of fighting, Geki Force lost at least 195 of its 220 tanks. No longer did Maj. Gen. Swift’s soldiers need to fear a mechanized counterattack. All that remained of Japan’s armored might on Luzon were a few three-vehicle platoons scattered across the island.

The last recorded tank versus tank fight in the Philippines took place during mid-April as American patrols neared Yamashita’s headquarters near Baguio. Outside of town, two Japanese tanks packed with high explosives made a suicide run against some Shermans of the 775th TB. Both vehicles managed to ram their targets, but neither charge detonated. Other M4s quickly knocked out these armored kamikazes. It was a fittingly courageous yet futile conclusion to the story of Japanese tanks on Luzon.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer and historian who writes from his home in Scotia, New York.

Great work, Pat. You should have presented this way back when at AOBC!

My father PFC Robert L. Toon, 6th Army, 35th Inf Div, Cannon Company was part of an M-7 Priest SP howitzer that fought in the Battle of Lupao. He won the Silver Star when a Japanese tank round killed 3 of the 5 crew and he and another soldier pulled their M-7 out of harm’s way.

Nice article. One correction, however. Captain Michael Kane, Jr., commanded Company “C,” 20th Infantry Regiment during the Battle of Muñoz, not Company “B.” The Company “B” C.O., Captain Edgar C. Boggs, was killed during the battle and was posthumously awarded the Silver Star Medal.

Morning reports documenting this:

https://www.6thinfantry.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/1945-02-20th-Inf-Reg-CO-B.pdf, https://www.6thinfantry.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/1945-02-20th-Inf-Reg-CO-C.pdf