By Peter Kross

On the morning of April 18, 1961, readers of the New York Times awoke to a startling headline: “Anti-Castro Units Land in Cuba; Report Fighting at Beachhead; Rusk Says U.S. Won’t Intervene. Premier Defiant. Says His Troops Battle Heroically to Repel Attacking Force.” The author of the article, Tad Szulc, a confidant of President John F. Kennedy, wrote that anti-Castro forces had landed in a swampy area of Cuba in Las Villas Province, supported by American air cover. The article said the unidentified rebels were making substantial progress in their landings and that Premier Fidel Castro had narrowly escaped injury in an air raid during the initial fighting.

Another headline in the same edition of the newspaper reported that “Moscow Blames U.S. For Attack.” The confusing nature of the two headlines made readers uncertain just what was taking place in Cuba, a communist-dominated nation a scant 90 miles off the coast of Florida. If the readers of the Times really knew what was going on, they would have been even more shocked. The attack at the Bay of Pigs that early April morning had been in the works for many months, its planning having begun in the last year of the Eisenhower administration. The overall goal of the attack, led by anti-Castro forces trained and equipped by the United States, had one common theme—the overthrow of the Castro regime and its replacement by forces loyal to the United States.

The Fall of Fulgencio Batista

The genesis of the Bay of Pigs took hold in the Cold War confrontations between the Soviet Union and the United States, but its roots trailed back to U.S. involvement in Cuban affairs beginning in the late 19th century. The Cuban dictator Fulgencio Batista had been ruling the island with an iron fist, repressing the people, using the nation’s thriving economy to divert millions of dollars to his personal use, and making a secret pact with members of the American Mafia who ran the lucrative casinos to receive a substantial cut of their casino profits.

In the 1950s, Cuba served the anti-communist purposes of the Eisenhower administration, which saw in Batista’s Cuba a convenient place to confront the communist menace that was threatening to spread across Central and South America. Eisenhower knew the sordid details of Batista’s cruel reign but chose to look the other way. The Central Intelligence Agency, under the direction of Allen Dulles, had made a pact with Batista for the dictator to do the agency’s bidding. Lyman Kirkpatrick, the CIA’s inspector general, made a visit to Batista in 1956 for a heart-to-heart talk. Batista’s goon squads were terrorizing anyone who was even remotely opposed to the dictator, and the United States had had enough of his heavy hand. The Americans insisted that Batista ease his oppressive policies. But Batista, emboldened by Mafia dollars, chose not to obey. The United States decided to end its long support.

In the wake of that decision, Batista’s hand was weakened, and revolution broke out, led by a ragtag band of insurrectionists hiding in the Sierra Maestra of central Cuba. A well-born attorney named Fidel Castro rose to lead the rebels, assisted by his brother Raul and a shadowy Argentinean revolutionary named Ernesto “Che” Guevara. After several victories by the rebels, Batista and his family fled Cuba for the Dominican Republic on New Year‘s Day 1959, taking with them at least $300 million in cash.

Waiting in the wings was Castro. Upon taking office, Fidel promised a new beginning for the Cuban people. Gone was the tyranny of the hated Batista regime, to be replaced by a government that was responsive to the will of the people. Castro’s ascension to power in Havana was eyed warily by the Eisenhower administration, which hoped Castro would not turn his nation into a way station for communist influence in the Western Hemisphere. On January 7, 1959, the United States officially recognized the Castro regime. It would be a decision American leaders would quickly come to regret.

The Decision to Overthrow Castro

One of Castro’s first moves after taking power was to close Mafia-run casinos. This was a positive sign, but Castro followed with more troubling acts: deporting dissidents, jailing his political enemies, nationalizing a number of American-owned factories, and making diplomatic overtures to the Soviet Union. Despite these moves, the U.S. State Department assured Castro of the continued goodwill of the American people. Meanwhile, CIA director Dulles reassured skeptical senators in a closed-door meeting that Castro did not have any communist leanings. The next month, however, Dulles reversed positions, telling the president that Castro was moving rapidly to turn Cuba into a communist state.

In mid-April, Castro made a highly publicized visit to the United States with the hope of meeting directly with Eisenhower. The president, however, had no interest in being anywhere near Castro, and he left Washington as soon as Castro landed. Castro went instead to the United Nations in New York City, where he made a stirring speech to the assembled delegates announcing his new revolutionary independence from the United States. Castro traveled like a conquering hero through the streets of Harlem, captivating many with his personal charisma, if not his politics.

Eisenhower directed Vice President Richard Nixon to have a one-on-one talk with Castro in New York. The meeting between the two hard-headed pragmatists was contentious, with each man taking the measure of the other. Back in Washington, Nixon told the president that in his opinion Castro was under communist influence “or at least incredibly naive about Communism.” Following his meeting with Castro, Nixon became convinced that the United States had to remove Castro from power, one way or another.

Once he was firmly cemented in power, Castro began to ruthlessly eliminate all remnants of the hated Batista regime. Summary executions of dozens of former police and military officials took place. Some 50,000 frightened citizens left for Miami, desperate to flee the increasing violence. In June, Castro further inflamed the United States when he took over several high-profile American businesses in Cuba, including large farms owned by the United Fruit Company.

The die was cast for a major confrontation between the United States and Cuba. Any peaceful reconciliation was out of the question. Events soon took on a life of their own. In Washington, the CIA began a series of intensive, high-level meetings. On December 11, J.C. King, the head of the CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division, wrote a memorandum to Richard Bissell, deputy director of Plans (head of the clandestine service, in other words), and Director Dulles. The memo stated that Castro had turned Cuba into a left-wing dictatorship and was threatening to lend Cuban support to revolutionary activity across Latin America. The memo said that “violent action” was the only means of breaking Castro’s hold on power and that “thorough consideration be given to the elimination of Fidel Castro.” The word “elimination” was a code word for assassination, a policy that would come back to haunt the administration in its efforts to remove Castro from power.

Operation Pluto

In March 1960, the Eisenhower administration began a secret plan to topple the Castro regime. Bissell was authorized to form a task force called “the Special Group” to devise an anti-Castro plan of action. A Cuban Task Force was started and a formal document prepared for its members. The document listed a number of goals: the creation of unified Cuban opposition to the Castro regime outside of Cuba, the use of mass communications in a powerful propaganda effort; the development of a covert intelligence organization within Cuba that would be responsive to the order of the exile opposition; and the development of a paramilitary force outside Cuba for future guerrilla actions on the island.

On March 17, Eisenhower signed a secret National Security Council directive greenlighting the program, which was code-named Operation Pluto. One of the most divisive issues in the Eisenhower administration was how to organize the various anti-Castro groups. The Cuban Revolutionary Council (CRC) was formed to serve as an umbrella group for all anti-Castro operations. The U.S. government still had a difficult time reconciling the groups’ various interests and getting their divergent leaders into one organized unit.

Another integral part of the planning was an intensive propaganda operation mounted by the CIA. The agency established a clandestine radio station called Radio Swan, a 50-kilowatt broadcasting facility station located on Swan Island in the Caribbean, near the coast of Honduras. Radio Swan broadcast news shows, entertainment, and anti-Castro speeches, all written by the CIA.

As originally planned, the initial military force would consist of 25 Cuban refugees who would be trained in sabotage and communications techniques and then infiltrated into Cuba. If needed, the number would expand to 75, but no more. These fighters would be modeled on World War II-era underground operations. Once inside Cuba, their main objective would be to link up with other anti-Castro forces and carry out small-scale hit-and-run raids against selected military targets.

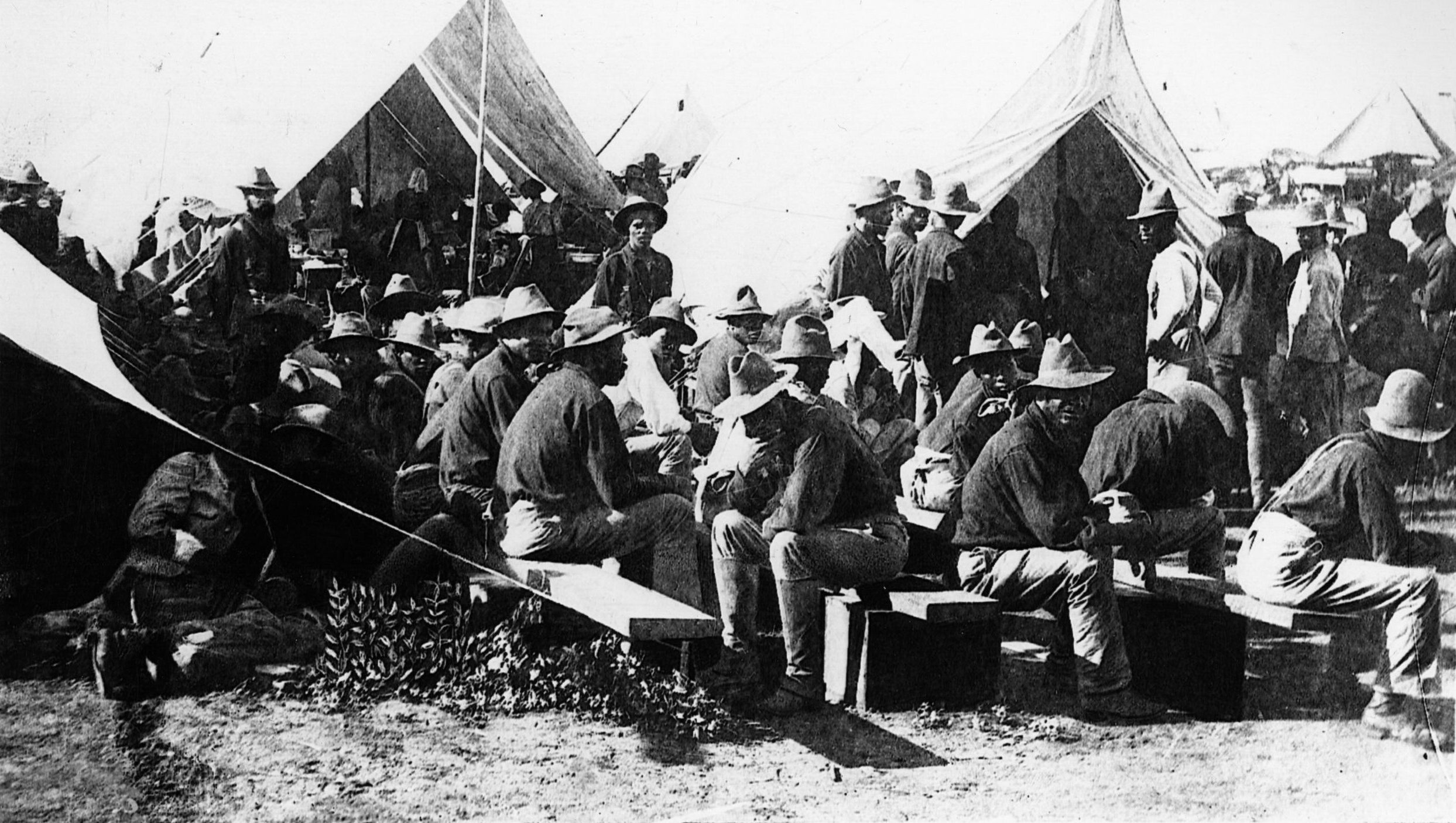

Training Anti-Castro Volunteers

The CIA began training about 300 men in military camps in Florida and Louisiana before moving them to the Panama Canal Zone. Soon the trainees were moved to Guatemala under an arrangement with President Miguel Ydigoras. A secure camp and airfield, given the name Base Trax, was provided for the trainees on the grounds of a lavish coffee plantation in the Sierra Madre near Retalhuleu, close to the Pacific Coast. By August, members of the brigade began to arrive in ever-greater numbers; by the end of August, over 160 men were training at the camp.

The anti-Castro volunteers erected barracks and trained under the watchful eye of 20 CIA instructors, many of whom were contract employees, including eastern Europeans, Mexicans, and Chinese. All was not cozy between the contract employees and the brigade members. Many of the CIA officials did not speak Spanish, and subsequent communications breakdowns often hindered instruction. On September 8, Carlos Rodriguez Santana, a member of the brigade, was killed in a training accident at Base Trax. In his memory, his assigned number, 2506, became the official designation of the exile forces—Brigade 2506.

For an invasion to succeed, an air wing was required, and the CIA began making covert arrangements, taking control of an outdated airline company, Southern Air Transport. Using old C-46 cargo planes, pilots ferried the trainees between Florida and Guatemala. The CIA began supplying the brigade with combat aircraft to be used in the invasion. The ad hoc air force, based at Retalhuleu, consisted of 15 B-26 bombers, five C-46 transports, and seven C-54s. Ignoring President Eisenhower’s orders that no Americans be involved in the invasion, some 80 Americans joined the rebel ranks, ratcheting up the danger another notch.

Besides the air arm, the CIA provided the exiles with their own small fleet of ships. Two old infantry landing craft (LCI) capable of holding 250 tons of equipment and 200 men were added to the ever-growing arsenal. Another, smaller component of the secret war was the airdropping of supplies to anti-Castro groups hiding in the rugged Escambray Mountains of Cuba. Some 68 covert flights took off from Retalhuleu, but only seven of the airdrops were successful.

A Full-Scale Landing

As the months passed, it was decided at CIA headquarters to expand the overall scope of Operation Pluto. The Cuban government had made an arrangement with the Soviet Union for the latter to provide them with new combat jets, and Soviet technicians had begun training Cuban aircrews. An invasion had to be carried out before these new resources could be effectively deployed.

The CIA’s Western Hemisphere Division ordered the invasion force to be expanded to 800 men and an entirely new invasion paradigm put into effect. The new operation would be a full-scale, World War II-style amphibious landing. Once the landings were successful, exile leaders would be brought ashore to establish a provisional government and formally ask for American aid. Jose Miro Cardona, the former Cuban prime minister, was the designated leader in waiting.

On January 3, 1961, Eisenhower finally had enough of Castro’s anti-American activities and severed official relations with Cuba. Castro immediately turned to the Soviet Union for military and economic aid. Aides to President-elect John F. Kennedy told the exiles they were on their own—no American troops would assist them in their landings. The nonuse of American troops was of vital importance to the incoming Kennedy administration, a decision that would have far-reaching consequences when the brigade landed on the shores of southern Cuba.

“A Fair Chance of Success”

On January 28, during his first week as president, Kennedy asked the Joint Chiefs of Staff to make a preliminary assessment of the Cuban invasion plans. The chiefs told the new commander in chief that in their opinion the invasion had “a fair chance of success” if it inspired a widespread uprising among the Cuban population. Despite the vaguely optimistic words, the president had lingering doubts about the impending invasion. Guatemala’s president urged Washington to speed up the invasion; he didn’t want the brigade to spend any more time in his country. Kennedy knew that if he didn’t act fast, he would have a similar problem on his hands. If he canceled the invasion, members of the brigade would be brought back to the United States, and there was no telling what they would say to the press or others about their secret training in Guatemala and the covert role of the United States in the planned overthrow of the Cuban regime.

In March, Bissell gave Kennedy and his top advisers a full-dress briefing on the invasion. The landing was scheduled to take place in the Trinidad section of Cuba, not far from the Escambray Mountains, a hotbed of anti-Castro resistance. The CIA believed that if the invasion failed, the men could successfully infiltrate into the mountains and carry out hit-and-run raids against Castro’s forces. However, there was one major drawback to the Trinidad site—the airstrip nearby was not capable of handling the arrival of the B-26 bombers that were vital to the success of the mission. Air cover would have to be flown in from other locations in Central America, thus making it more difficult for the invasion forces once they hit the beaches.

Kennedy worried about the speculative nature of the Trinidad plan. As he saw it, the invasion smelled more and more like an American-sponsored attack, the one thing he had made abundantly clear must not happen. The president ordered the military to come up with a substitute plan, one that would center on a nighttime invasion, not a daytime attack. Trying to dampen rumors of an imminent U.S. invasion of Cuba, the president somewhat disingenuously told a press conference, “There will not be, under any conditions, an intervention in Cuba by the United States armed forces.”

A new invasion site was chosen: the Bay of Pigs area in the Las Villas Province of southern Cuba, 90 miles southeast of Havana. The new area had an airstrip long enough to handle B-26 bombers coming in from Central America. The revised plan called for the invaders to seize three beaches along a 40-mile stretch of Cuba coastline, cross a wide swamp, and make their way to the mountains 50 miles away. Paratroopers would be dropped to seize certain key areas and hold back Castro’s forces. The new plan was given the code name Zapata. The plan called for a diversionary force of about 160 men to be landed in eastern Cuba two days before the main invasion. Air strikes would also take place, supposedly from “defecting” Cuban pilots.

While military planning continued, in the White House the president had one final option open to him: he could cancel the invasion up to 24 hours prior to attack. The time of the assault was put back from April 12 to April 17. Due to the change of plans, Brigade 2506 did not depart from Guatemala, but rather from Puerto Cabezas, Nicaragua. The flotilla consisted of two CIA ships, Blagar and Barbara J. Five other vessels were chartered by the Garcia Shipping Line to ferry men to the Bay of Pigs. Brigade members packed up Base Trax and headed for Cuba.

As final preparations for the landings took place, the U.S. Navy reinforced the long-held American base at Guantanamo in case Castro retaliated once the invasion began. Admiral Robert Dennison ordered a number of Navy ships to assist brigade members as they neared Cuban shores. The carrier Essex would be the flagship of the group; its planes would provide air cover if needed. Two destroyers, Eaton and Murray, would act as convoys and escort the brigade’s ships as close as possible to the Bay of Pigs. Another Navy ship, San Marcos, carried landing craft for the invaders.

“We’re Hanging on by Our Fingernails”

The first action took place via air, as the brigade’s air force mounted operations to take out Castro’s air arm. Castro’s air force was small, comprising six B-26 bombers, four T-33 trainers, and four British-made Sea Fury Fighters. A limited strike on the planes took place on April 15, resulting in the destruction of half of Castro’s aircraft. The CIA requested another air strike to take out the remainder of the Cuban Air Force, but a personal appeal by Secretary of State Dean Rusk couldn’t persuade the president to authorize another air strike. Once Brigade 2506 hit the beaches, the invaders would be on their own.

After the initial air strike took place, Castro mobilized his 200,000-man militia and arrested thousands of dissidents who might help the invaders once they waded ashore. As soon as Castro realized that the Bay of Pigs was the main target, he rushed a number of Russian-made T-45 tanks and troops to the area to repel the invasion. Meanwhile, a parachute regiment of Brigade 2506 landed 16 miles inland, but lost most of its ammunition in the process. Already, things were beginning to fall apart for the invasion team.

The invaders were supposed to land at Red Beach, located at the northernmost area of the Bay of Pigs; Green Beach, about 20 miles east; and Blue Beach, farther to the east. The landing craft immediately ran into trouble when they hit coral reefs that weren’t supposed to be there. By dawn on April 17, most of the invaders had successfully arrived at Blue Beach, but without the 72 tons of ammunition they initially planned to take with them. The ammunition and supply ships were still offshore, within range of Cuba’s air force. Using two coordinated strikes, Castro’s planes attacked the ships Houston and Rio Escondido, sinking both. The ships carried tons of supplies, as well as 130 men of the 5th Battalion. The survivors swam for shore and were picked up by U.S. Navy ships. Rio had carried all the brigade’s communication and aviation gasoline. After the air strike, the landing at Green Beach was canceled and the remaining troops were ordered to rendezvous with the Navy offshore.

By D-day plus 2, Castro’s main army had bottled up the brigade members on various fronts around the Playa Larga. Heavy armored vehicles and thousands of regular army units had the invaders all but surrounded. On the second day, rebel B-26s attacked Castro’s troops but did no real damage. To make matters worse, four civilian American fliers—Riley Shamburger, Wade Gray, Willard Ray, and Leo Baker—were shot down and killed in the attacks.

As Castro’s forces took the offensive, the members of the Red Beach contingent joined those of Blue Beach in a brave effort to stave off the constant bombardment. Units of the airborne brigade also retreated toward Blue Beach. On the afternoon of April 17, the Joint Chiefs of Staff ordered the military to set up a safe haven for the surviving brigade ships with American air cover, but with restrictive orders to operate 50 miles from Cuban shores in international waters. No American aircraft were to be allowed within 15 miles of the beachhead. As dire reports filtered into the White House, the president told his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, “I don’t think it’s going as well as it should.”

While the brigade was fighting for its life, CIA chief Allen Dulles had left Washington for a speaking engagement in Puerto Rico, leaving Bissell and his subordinates to monitor events in Cuba. Upon his return to Baltimore, Dulles was met by a colleague who told him ominously, “We’re hanging on by our fingernails.”

Resistance Ends on Blue Beach

In Washington, Kennedy attended the annual congressional reception. At midnight, he left for a hurried meeting in the cabinet room. Still dressed in formal attire, the president met with Vice President Lyndon Johnson; Secretary Rusk; Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara; General Lyman Lemnitzer, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff; Admiral Arleigh Burke; and Walt Rostow, JFK’s national security adviser. During the meeting, the president allowed one last attempt to save the deteriorating situation. He authorized a flight of six unmarked jets from the carrier Essex to fly over the Bay of Pigs one hour after dawn the next day to serve as cover for an air strike by B-26s from Nicaragua.

The planes were supposed to fly over the beach between 6:30 and 7:30 am. However, due to a mix-up, they arrived too early, and two of the B-26s were shot down. As a last resort, the president told Admiral Burke to inform the CIA that, in the event of imminent defeat of the brigade, “it would be desirable for them to become guerrillas and head for known destinations and be supplied by air.”

The remaining members of Brigade 2506 fell back toward Blue Beach, where all further resistance ended. In Washington, military officials were intensely monitoring the fighting on the bloody beaches. Jose “Pepe” San Romain, one of the brigade leaders, radioed Washington and in a desperate voice that could be heard by all in the room, said: “I have nothing left to fight with. Am headed for the swamp.” Minutes later his radio went dead. Some 114 members of the brigade were killed, another 1,189 captured. The prisoners would remain in Castro’s jails for another 18 months before being ransomed by the United States for $62 million worth of medicine and food.

Fallout From the Bay of Pigs Invasion

Days after the debacle, Kennedy met with Eisenhower at Camp David, where the two men had a heart-to-heart discussion of the events in Cuba. Eisenhower was aghast that the United States had not provided air cover to the rebels. “How could you expect the world to believe that we had nothing to do with it?” he asked incredulously. Kennedy replied that the American people “would never approve direct military intervention by their own forces, except under provocations against us so clear and so serious that everybody will understand the need for the move.”

In the wake of the fiasco, Kennedy fired Dulles; Bissell; and General C. Pierre Cabell, Dulles’s second-in-command, replacing Dulles with Republican businessman John McCone. Shortly after the affair ended, Kennedy appointed a commission headed by General Maxwell Taylor to look into the facts behind the Bay of Pigs. The commission held 20 hearings and met with a host of people, including American military men and surviving brigade members. After a lengthy process, the committee concluded that the failure was “attributed to a mistaken belief that this large operation could be conducted with plausible deniability; to a lack of coordination among U.S. agencies; to attempt to command from a distance, with headquarters at Washington.”

The CIA itself conducted its own secret investigation into the failure. This report, which was only recently declassified, was a harsh indictment of the CIA and its role in the Bay of Pigs fiasco and concluded that all the assumptions about Castro’s vulnerability were flawed and that poor exile training and lack of coordination between the various military agencies led to what one writer called “the perfect failure.”

Eighteen months later, the United States and the Soviet Union came dangerously close to nuclear war after the Soviets secretly placed intermediate-range missiles in Cuba to deter any future anti-Castro attacks. The 13-day crisis in October 1962 ended peacefully after the United States placed a naval quarantine around Cuba and Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev agreed to remove the missiles in exchange for the U.S. removal of similar missiles in Turkey. Who blinked first is still debated.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments