By Christopher Miskimon

Petty Officer R. J. Thomas, a U.S. Navy SEAL, wound up in deep trouble one day in 1969. As he was riding in a UH-1 Huey helicopter gunship during a scouting mission, the aircraft was hit by enemy fire and crashed, killing or wounding everyone on board. Despite serious injuries, Thomas helped drag the flight crew away from the downed helicopter. Within minutes, a group of North Vietnamese Army and Viet Cong troops arrived and approached the wreck. The only weapon the American had at hand was a Model 1911A1 .45 Automatic pistol.

Unfortunately for his enemies, Thomas was a competitive shooter for the U.S. Navy as well as a SEAL. He opened fire on the advancing Vietnamese at 100 yards, a range beyond the skill of a typical pistol user. Thomas proved quite atypical, hitting his target and forcing the rest to advance more slowly and cautiously. For the next 30 minutes, he kept his enemy at bay with careful shots from his .45. Depending on which account is accurate, Thomas killed between 10 and 37 soldiers. More SEALs soon arrived and laid down covering fire while an Army gunship landed to extract Thomas and the flight crew. Nearly out of ammunition, he shot one more Viet Cong as he was pulled aboard the helicopter.

Thomas’ actions present an extreme use of a pistol in combat, but the .45 automatic pistol is a weapon well-suited to extremes. It served as the official sidearm of the U.S. Military for more than 70 years and still sees use in Special Operations units today. Prized for its reliability and stopping power, foreign militaries have also used the Model 1911, and it has been made under license or simply copied around the world. It likewise has been popular with law enforcement and in civilian hands as long as it has been a military weapon.

Variously known as the Colt .45, 1911, or simply the .45, the pistol’s origin begins at the turn of the 20th century, when American troops became involved in a protracted counter-insurgency campaign in the Philippine Islands after the Spanish American War. Some Filipinos did not wish to exchange their Spanish overlords for American ones. Among these insurgents were the Moros, a native tribe known for their martial prowess. Moro warriors reportedly used drugs before combat to heighten their ability to withstand wounds, and they often tied tight wrappings around their limbs to slow blood loss. The standard-issue handgun at the time was the Colt .38-caliber revolver, but it performed poorly against the Moros, even when an American emptied his revolver into the warrior at point-blank range. Old .45 Colt Single Action Army revolvers pulled from storage were hurriedly issued to troops in the Philippines, but it was clear a more modern and powerful handgun was needed.

The Army decided the new handgun had to be of at least .45 caliber. The officers overseeing the tests, Colonel John T. Thompson and Major Louis LaGarde even used live cattle in the Chicago stockyards as test subjects. Thompson is best known as the inventor of the Thompson submachine gun, also a .45-caliber weapon.

Trials for the new handgun began in 1907and eight gun makers submitted weapons. While semiautomatic pistols were making great strides in performance and reliability, the notice allowed either semiautomatic pistols or revolvers, provided they used a .45 caliber cartridge. Weapons arrived from Colt, Smith and Wesson, Savage, White-Merrill, Bergman, firearms inventor William Knoble, and British firm Webley and Scott. The German Company DWM submitted a .45 caliber Luger.

Of the semiautomatic designs, only those from Colt, DWM, and Luger proceeded past the initial review. Soon DWM dropped out, deciding production of their Luger in .45 was not cost-effective. Both Colt and Savage received orders for 200 pistols for testing. Once in hand, samples went to field units, the School of Musketry, and the boards of infantry, cavalry, and field artillery. Neither weapon proved ready for adoption, with both suffering the usual problems of prototypes. The Colts had issues with jamming and broken parts, while the Savage’s magazine tended to fall out during firing. Savage quoted a production price of $65 per pistol while the Colt came in at $25. A second round of testing was ordered in 1910.

For the next tests, the Colt resembled the weapon as later adopted, but still suffered four parts failures. The Savage had 13 failures and showed excessive recoil. The military scheduled a third round of trials for 1911. During these tests, evaluators fired 6,000 rounds through each weapon. The Savage suffered thirty-seven malfunctions or broken parts. The Colt functioned flawlessly and was more accurate. The War Department’s choice was clear, and the Colt officially became the Model 1911.

The final price for the 1911 was $14.25 for a pistol and one magazine. Spare magazines were valued at .50 cents each. On April 21, 1911, the first contract went out for 31,344 pistols with two spare magazines apiece, plus spare parts and other equipment. The whole contract totaled $459,988.77. A provision enabled the government to produce the weapon itself, provided a $2 royalty was paid to Colt and 50,000 pistols were purchased from Colt first, and Colt had to produce two-thirds of all of the weapons made. The government’s Springfield Armory started making 1911s within a few years at a cost of $13.25 each, including the royalty. By the end of 1917, Colt’s production totaled 80,000 pistols with another 25,000 made by Springfield Armory, which also produced the M1903 rifle.

The 1911 is a hefty pistol, weighing 39 ounces unloaded. The barrel is five inches long with a small set of fixed sights atop the slide. The standard magazine holds seven rounds of .45 Automatic Colt Pistol ammunition. The original .45 cartridge has a full-metal-jacketed projectile weighing 230 grains, which travelled at 850 feet per second. The .45 bullet weighed twice as much as the standard 9mm projectile of the time. The standard military load has remained the same, although improved hollow-point ammunition exists for law enforcement and civilian users.

With a prestigious military contract in hand, Colt soon produced a version of the 1911 for commercial sale. These pistols were marked “Government Model” to link them to the military version. Even before World War I began in 1914, British officers bought them privately, and many were made in .455 Webley Automatic caliber, since that cartridge was in use in the British military. No one is certain of the Colt’s first combat use, but it likely occurred in British hands somewhere in the British Empire. American troops first used them in combat in 1913 in the Philippines and in 1914 during the Vera Cruz landing; U.S. Marines carried them in Haiti in 1915, and they were widely issued to U.S. Army troops during the Punitive Expedition in Mexico in 1916-1917.

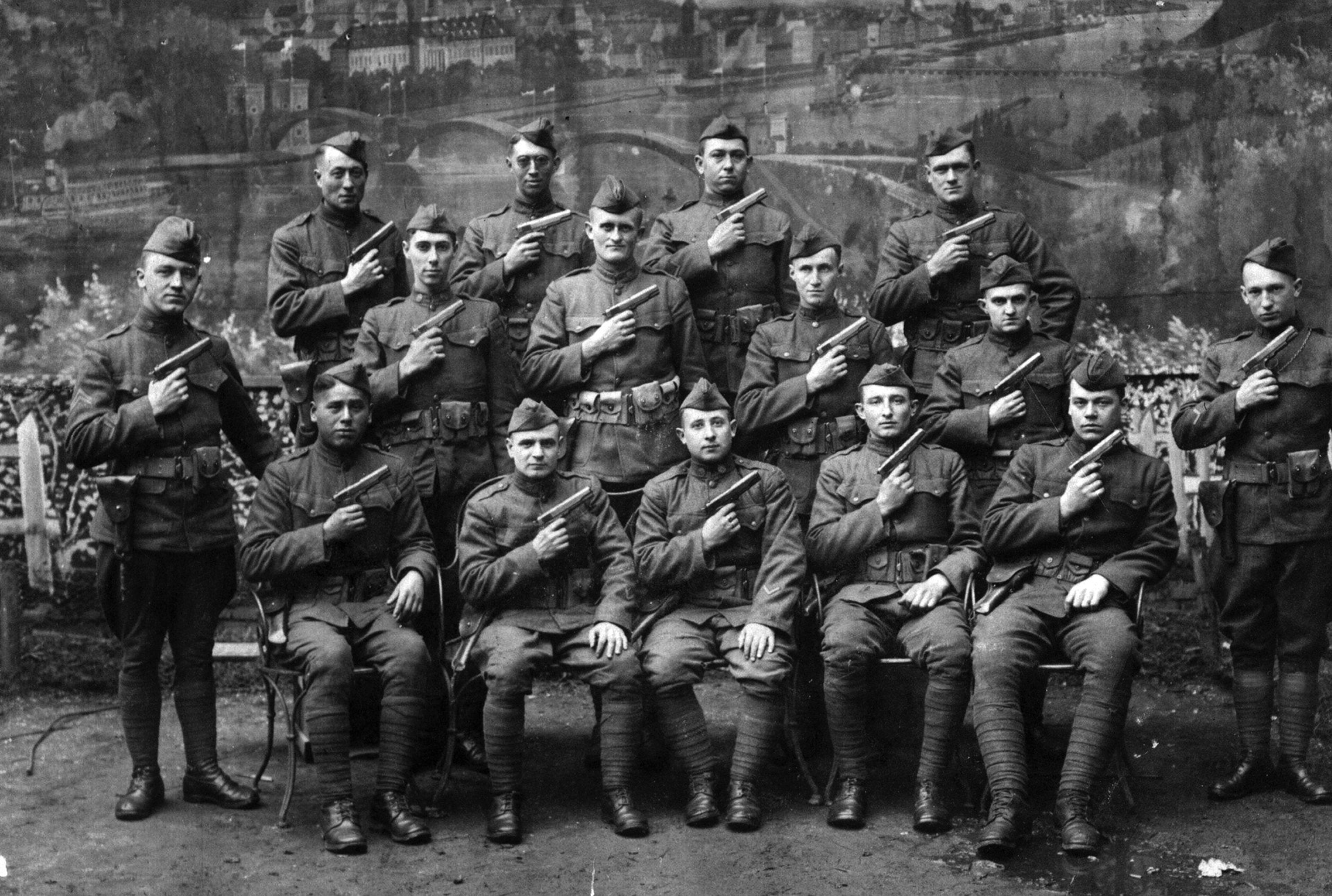

The first real test, though, for the Colt automatic came during World War I. By the time the United States entered the war in April 1917, nearly 70,000 pistols had been delivered to the military, with orders in for another 141,000. By the end of the war, another 446,000 were delivered. Additionally, the British government later bought thousands of 1911s for service use. Canada and France procured about 5,000 each, and the Russians bought 51,000, many of which later fell into communist hands.

A pistol was a handy weapon to have for close-quarters trench fighting, and troops appreciated the .45’s power. Soldiers conducting trench raids often carried .45s along with shotguns, clubs, entrenching tools, and knives.

The most famous soldier to wield the Colt during the war was Corporal Alvin York of the U.S. 82nd Division. York went on a patrol with other American troops on October 8, 1918. While on that patrol, the Americans attempted to outflank a German machine-gun position. They took a group of prisoners but were fired upon as they prepared to take the German prisoners-of-war back to American lines. German fire cut down nine doughboys, including the sergeant in charge. York took command and ordered the surviving Americans to guard the prisoners while he attacked the enemy. York, an expert marksman, killed a German machine-gun crewman with each shot. Another group of Germans counted his shots and charged when they knew his rifle was empty. York shot them all with his .45 pistol. He killed 25 Germans that day and captured 132 more, earning a Medal of Honor and promotion to sergeant.

The British also had famous users of the 1911. Colonel Thomas Edward Lawrence received a pair of 1911s as a gift and carried them both during his service in the desert. Lieutenant Colonel Winston Churchill also purchased a 1911, had it engraved with his name, and carried it during his frontline service. When he was prime minister during World War II, he loaned it to his bodyguard, Walter Thompson, to replace the police-issue Webley .32 automatic. He sometimes carried it himself, tucked in his trousers.

After the war, the U.S. Military decided on a few improvements to the 1911, including a shorter trigger, arched mainspring housing on the rear of the grip, and an extension to the grip safety to keep shooters with larger hands from being painfully pinched by the weapons hammer when it was re-cocked during firing. The upgraded pistol became the Model 1911A1, with the A1 standing for “Alteration One,” and served the U.S. Military from 1924 until long after its official replacement in the 1980s. Between World War One and World War Two, the .45 saw military service by the Americans in Central America and the Caribbean.

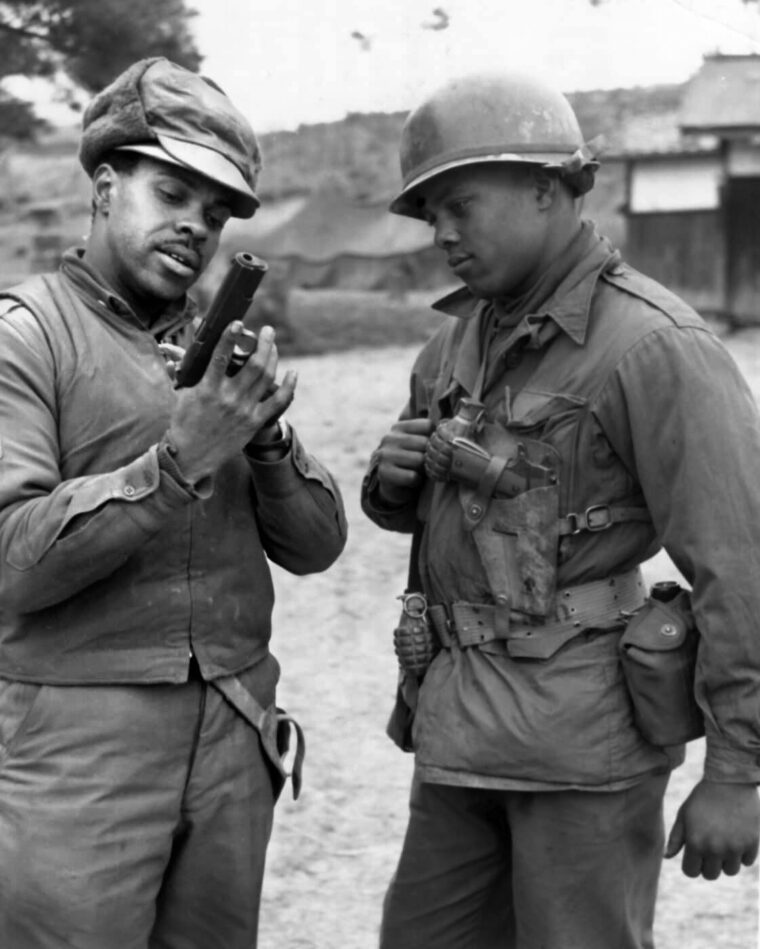

During World War II, the 1911A1 served as the standard-issue pistol, supplemented by leftover .45 revolvers and Colt and Smith and Wesson .38 revolvers. To meet the huge demand for more pistols, several companies undertook production of the .45, including Remington Rand (877,751 pistols), Ithaca Gun Company (335,466), and the Union Switch and Signal Company (55,000). Colt made another 629,000 during the war.

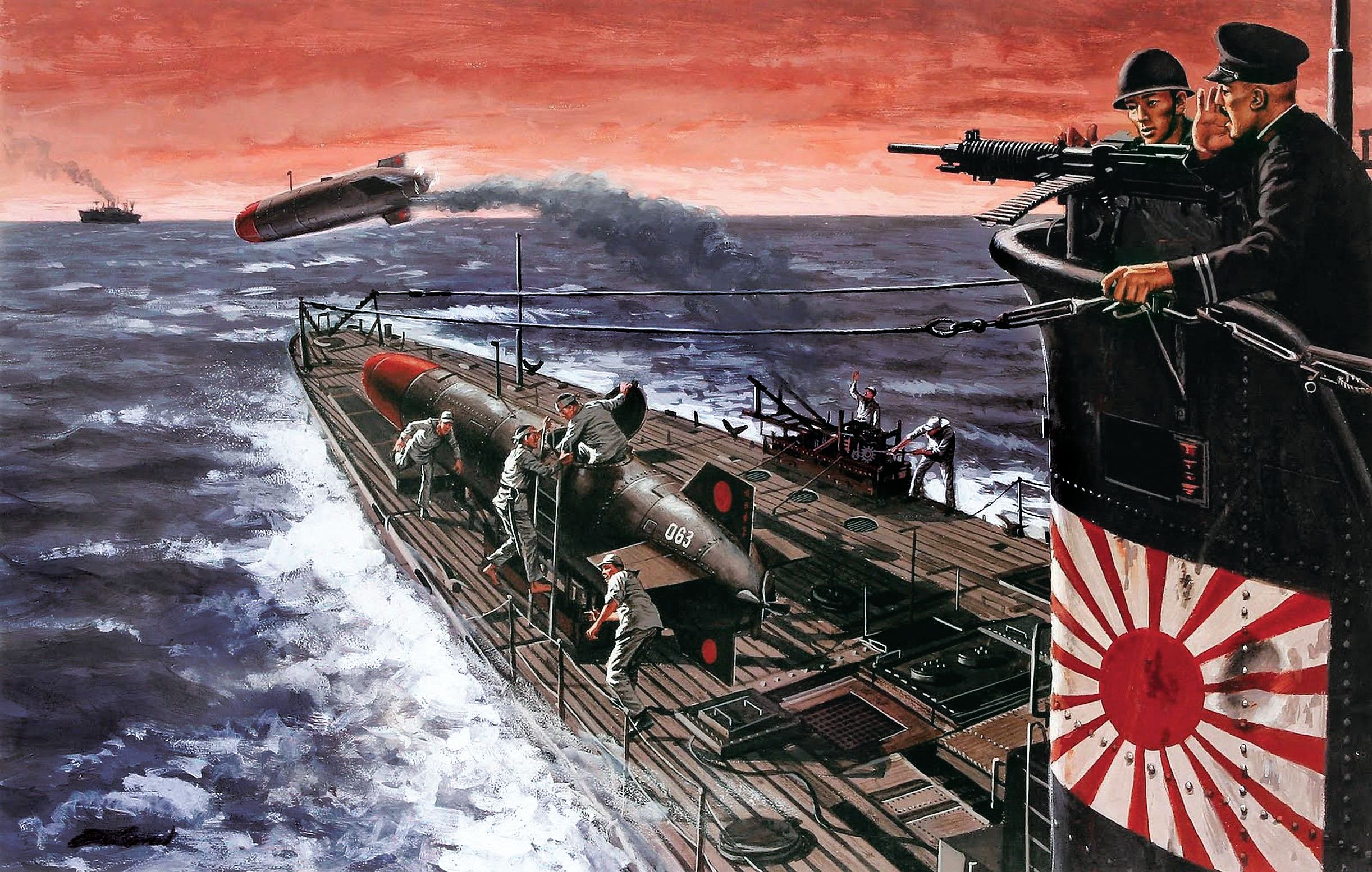

Stories of the .45 in combat abound. Colonel Walter Walsh, in peacetime an FBI agent and renowned marksmen, shot a Japanese sniper through the embrasure of a bunker at more than 75 yards with his pistol. Second Lieutenant Owen Baggett served as co-pilot on a B-24 in the Pacific. His plane shot down, he bailed out with other crew members, but the Japanese fighter pilots began strafing the helpless parachutists. As one of the enemy planes flew close to check their handiwork, Baggett raised his .45 and fired, killing the pilot. A Japanese officer later stated the pilot died from a single shot to the head. During the Battle of the Bulge, antitank gunner Corporal Henry Warner of the 1st Infantry Division knocked out two panzers with his 57mm cannon. After it jammed, he pulled out his .45 and shot at a German tank commander standing in the hatch of his tank; as a result, the panzer crew retreated. Warner was killed the next day after knocking out another tank. He received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Many soldiers carried the M-1 Carbine during the war, a light rifle designed to replace the pistol; however, stories abound of the .45’s stopping power being superior to the diminutive rifle. In the Philippines, two American pilots sat in their tent when a group of native headhunters attacked. One pilot had a carbine and shot a headhunter twice in the chest to no effect. As the native raised a machete, the other pilot shot him once in the forehead with his .45, dropping him instantly. The carbine was quickly traded for a .45. During the Battle of Iwo Jima, as a Japanese soldier charged a group of Marines, an American emptied a 15-round clip into the enemy soldier, who kept coming at the Marines. Another Marine drew his .45 and put the Japanese down with a single shot to the chest. While such stories are largely anecdotal, they spread widely among GIs, who had faith in the hitting power of their trusted .45s. Thousands of the legendary Colt 1911s were kept as souvenirs after the war, smuggled home in the duffle bags of returning servicemen. Today they are prized heirlooms and expensive collector’s items.

Why no mention of the inventor/developer of the Yankee Fist, John Moses Browning?