By Kevin M. Hymel

This article is excerpted from Kevin Hymel’s latest book, Patton’s War: An American General’s Combat Leadership, Volume 2: August—December 1944, published by University of Missouri Press. Volume 2 follows General Patton across France as he helps close the Falaise Pocket, races to the Moselle River, captures Metz and relieves Bastogne.

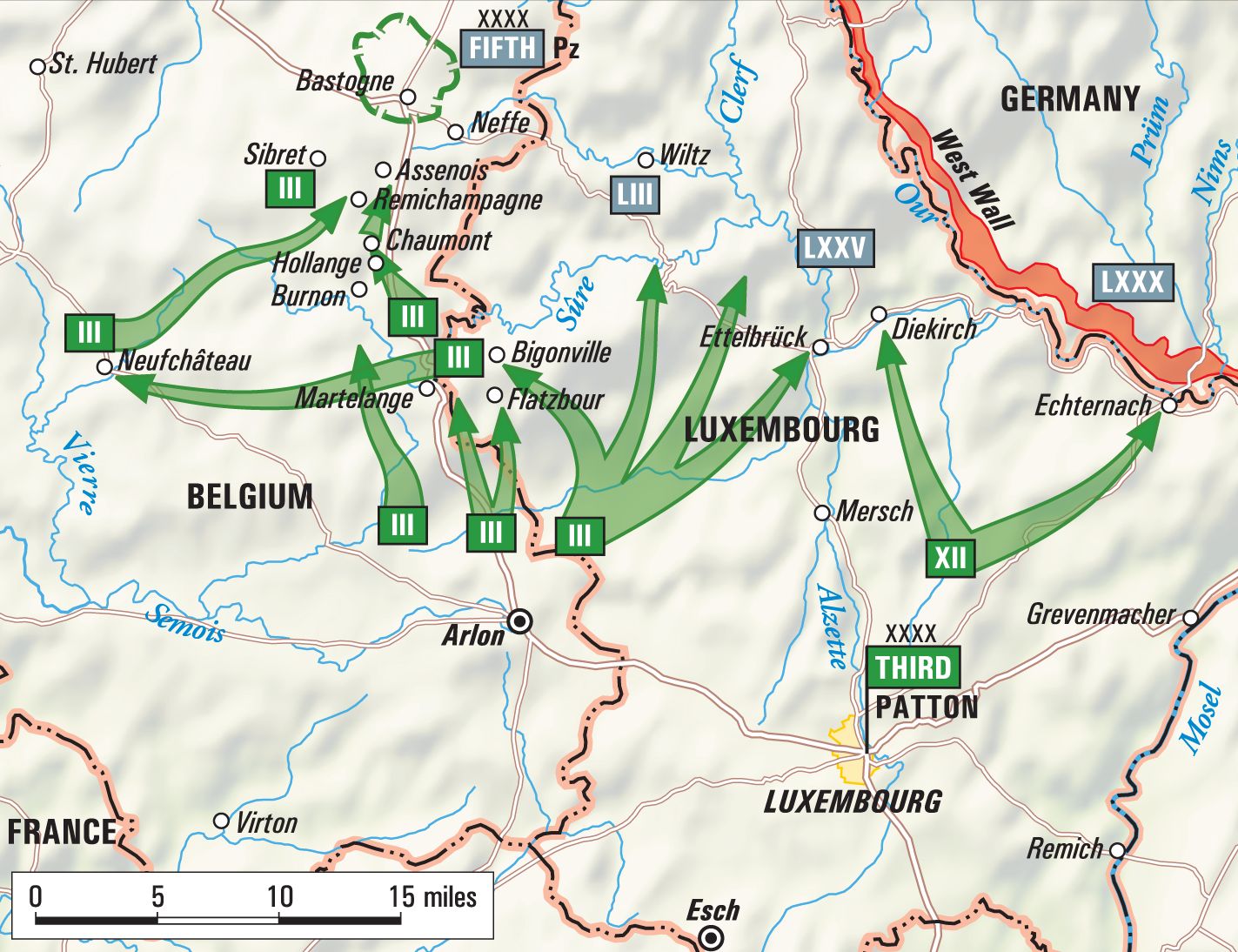

On the morning of December 22, 1944, at 6:30 a.m., Lieutenant General George S. Patton launched a two-pronged attack through the Ardennes Forest into the left flank of the German offensive during the Battle of the Bulge. He had spent the last four days turning two of his three corps north to both relieve the besieged Belgian town of Bastogne and recapture the Luxembourg town of Echternach.

While Bastogne seemed more urgent—where paratroopers from Brigadier General Anthony McAuliffe’s 101st Airborne Division and tankers and infantrymen from various units had been holding out since December 19—Echternach was just as important to Patton. If he could retake the town, he could simultaneously protect his drive for Bastogne, limit the width of the German offensive, and take the first step toward closing the bulge at its base.

Major General John Millikin’s entire III Corps pushed north toward Bastogne that morning, while only part of Major General Manton Eddy’s XII Corps—Major General LeRoy Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division—battled northeast toward Echternach later in the day in an attack across a 30-mile front. From west to east, Milliken’s III Corps consisted of Major General Hugh Gaffey’s 4th Armored Division, Major General Willard Paul’s 26th Infantry Division, and Major General Horace McBride’s veteran 80th Division.

Gaffey’s 4th Armored got off to a slow start, stymied by craters and blown bridges, but his tanks got rolling later in the day. Gaffey had three combat commands under him: Brigadier General Herbert Earnest’s CCA; Brigadier General Holmes Dager’s CCB; and Colonel Wendell Blanchard’s CCR (Reserve).

Earnest’s CCA reached Martelange while Dager’s CCB reached Menufontaine, about seven miles northwest of Earnest, which, incidentally, freed a number of 28th Division soldiers. Both towns bordered on the Sûre River and both commanders also fought through the night to establish bridgeheads, but Dager pushed further north, to the town of Burnon, creating a gap between the two commands, forcing him to stop and wait for Earnest’s force to catch up.

While Gaffey’s engineers raced to build bridges across the Sûre, General Paul’s 26th Infantry Division made good progress against German delaying actions. General McBride’s 80th Infantry Division had the toughest fight, running up against a defended river line which stalled his division until after dark, when the infantry finally broke through the German lines and pressed north. To confuse the enemy about the offensive, the 23rd Headquarters Special Troop transmitted fake radio traffic between Gaffey and McBride’s headquarters, discussing how they were going into reserve, away from Bastogne.

As the attack progressed, Patton called a staff meeting at 11 a.m. and immediately referenced the weather. “The Lord kind of played me a dirty trick,” he said before breaking into a smile, “but maybe he knows better, but we sure could have used some good flying weather, [although we] killed a lot of Germans.” When a message arrived from Millikin, Patton lamented the possibility of him getting killed on his first day in battle. “This is a big day for him,” he told the staff. “[It will] make him or break him.”

Six hours after Millikin’s tanks and infantry started pushing north, up at Bastogne a group of German soldiers carrying a white flag approached the American perimeter with a surrender ultimatum. Glidermen from the 101st Airborne blindfolded the Germans and escorted them to McAuliffe’s headquarters.

McAuliffe had been asleep when word came through about the ultimatum. “Nuts!” he said, as he roused from his sleeping bag. The Germans demanded he surrender by 4 p.m. or Bastogne would be annihilated by German artillery fire. McAuliffe had been in communication with General Troy Middleton, commander of VIII Corps, and although he never mentioned it, he knew that Patton was on the way. At first, McAuliffe thought the Germans wanted to surrender to him. When one of his staffers explained that it was the other way around, he exploded with anger. “Us surrender, awe nuts!” Still, he was not sure how to respond to the ultimatum until one of his staff officers suggested the word “Nuts.”

The response was typed up and given to the Germans, who were blindfolded again and escorted out. When one finally read the message and asked what it meant, one of the American escorts told him, “It means go to hell.” The response became an inspirational mantra to both the men inside Bastogne and those fighting towards it.

Patton found Millikin doing better than he expected. His men and tanks pushed forward in the snow, fighting and overcoming destroyed roads and bridges. Patton encouraged his new corps commander “to go up and hear them whistle.” He then took his own advice and visited some forward positions. At one command post which had undergone a tremendous pounding from German artillery, he entered the cellar and soldiers began to stand up to salute. Suddenly, a shell slammed into a building across the street. The lights dimmed, dust poured down and everyone lay flat—except for Patton. He just stood there, took off his helmet, and brushed off the dust. Three or more shells followed, but Patton stood unshaken. “What’s the matter boys?” he asked. “Are you expecting trouble up here?”

When Patton encountered a company of trucks with trailers plodding slowly north, he stopped one of them and ordered the driver to remove the trailer so he could advance faster. He also came across eight soldiers from the 28th Infantry and the 9th Armored who had spent the last four days walking southwest from Wiltz after their divisions had been decimated in the opening days of the campaign. While they had trekked through 27 miles of enemy-held territory, they only saw seven Germans, leaving Patton to speculate, “I think that perhaps there is less weight in the middle of the salient than we think.”

Patton returned to the Alpha Hotel in Luxembourg City, where his staff had set up his headquarters. “I think we achieved complete surprise,” he told his staff. “[With] no artillery preparation, [we] just moved off and caught them cold, tit for tat.” While Millikin made his move on the left flank, Patton wanted Eddy’s XII Corps to attack on the right. But not enough of Eddy’s troops had arrived yet for a punch equal to Millikin’s. Instead, Patton would use elements of Irwin’s 5th Infantry Division to seize the high ground around Echternach in preparation for Eddy’s larger corps offensive.

Patton spent the later part of the day concerned about Irwin’s attack. It launched around noon and ran into an attacking German force, leaving Patton waiting for word of the battle’s results. Although Irwin had initiated the action, Patton decided to hold off any major offensive by Eddy until he had driven the Germans east across the north-to-south running Sûre River.

Around noon the skies cleared and would remain that way for the next five days. The collective prayers of Third Army had been answered. Brigadier General Otto Weyland’s fighter-bombers of his XIX Tactical Air Command pounded German rear areas, averaging 570 sorties a day. Pilots shot down enemy aircraft, strafed troop and fuel trucks, tanks, railway cars, and gun emplacements. They blew up oil dumps and cut highways. Some pilots dropped napalm on antiaircraft units. They pulverized buildings at strategic intersections, making the roads impassable for the Germans. Still, on December 22, despite the clear afternoon skies, the airfields where the C-47s launched were too icy for operations, scrubbing an aerial resupply of Bastogne.

The resupply cancellation chafed Patton. He marched into the office of Major John Carvey, the officer in charge of the drop, and yelled at him, “Major, your Goddamned mission was a failure.” Carvey agreed, only to leave Patton glaring at him. “Well, what are you going to do about it?” Carvey, shaking and stammering, explained that he had already scheduled a second drop.

“Are you scared of me?” Patton asked. When Carvey told him he was, Patton asked him if he was married. When Carvey responded in the negative, Patton smiled. “Major, I want you to make me a promise,” he told the young man. “When you get back to the states, the first thing you’re to do is to get married. After you’ve been through the hell of married life, there will be nothing that I can say to you that will frighten you again.”

Patton knew time was of the essence and hoped for Gaffey’s 4th Armored to break through. “The situation in Bastogne is grave,” he wrote. “I will try to get Dager [commander of CCB] there tonight.” Patton’s hopes were way too high for the situation. When he later realized the Germans were using the same delay and retreat tactics they employed against him at Metz, he exploded. “Hell, why didn’t those [blank] come at me? If they want to pick on somebody, I’ll take care of those [blank]!!” Finally, he calmed himself and admitted, “They must have some smart men running the show.” Patton, too, had proved himself a smart man, having managed to move the bulk of his army, 250,000 men, from battling east along the Saar River to attacking north—an impressive feat in any terms. Worried about relieving Bastogne, he sent a message to Millikin that the advance was to be continued throughout the night.

Patton was satisfied, although not happy, about the day’s results. “I should be content which of course, I am not,” he wrote his wife Beatrice, knowing the difficulties of attacking in a snowstorm. “It’s always hard to get an attack rolling,” he penned in his diary, yet he doubted if the Germans would be able to launch any kind of attack against him for the next 36 hours. “I hope by that time we will be rolling. The men are in good spirits and full of confidence.”

By the next morning, December 23, Patton’s prediction of reaching Bastogne again proved too optimistic. While 4th Armored engineers spent most of the day repairing bridges over the Sûre River, tankers and armored infantrymen fought on little sleep and in temperatures cold enough to freeze the water in their canteens.

Germans ambushed the tankers of Earnest’s CCA about two miles north of Martelange, hitting them with small-arms fire, mortars and Panzerfaust anti-tank weapons. Earnest struggled to advance one more mile to the outskirts of Warnach. Blanchard’s CCR tried to capture Bigonville, three miles west of Earnest’s force, but dueled with German paratroopers and tanks (and a captured American tank in German service) just south at Flatzbour.

Dager’s CCB took the worst hit. Reaching the outskirts of the small town of Chaumont, about six miles ahead of Earnest, it looked like CCB would bolt the last six miles into Bastogne before sundown. But as Major Albyn Irzyk’s tanks surrounded and entered Chaumont at the bottom of a bowl-shaped depression, the Germans counterattacked with infantry, paratroopers, StuG III tracked assault guns, and Jagdtigers—heavy tank destroyers resembling Royal Tiger tanks but firing a 128mm shell (as opposed to the Tiger’s 88mm shell). By the time the smoke cleared, the Germans had destroyed or disabled 18 of Irzyk’s tanks, roughly half his force. Patton’s best bet to quickly reach Bastogne had been stopped cold.

Worried about Millikin’s lack of progress, Patton called the III Corps commander but only reached his chief of staff, Colonel James Phillips. “The going wasn’t so good yesterday, I’m unhappy about it,” Patton told Phillips. “I want to emphasize that this is a ground battle and they must move forward. Get them to bypass towns and get forward. I want a definitive report at 1315 today on the situation.”

Then Patton dropped a bomb: “I want Bastogne by 1350.” He wanted Millikin to traverse 10 miles of German defenses and icy roads in less than three hours. Then he explained why. “I have to give it to my boss at that time.” He concluded, “Get those boys moving, tell Millikin to get them going if he has to go down to the frontline platoon and move them!” Phillips agreed, and Patton hung up.

Patton hoped for better success with Eddy. He brought the XII Corps commander into his situation room to show him options to attack. While Patton sat on the edge of a desk, Major Robert Allen, an intelligence officer, encouraged Eddy to launch a diversionary attack on the German city of Trier, thus enveloping the Germans’ western flank. Patton then went outside and saw the skies clear. The C-47s were able to drop supplies to the surrounded men in Bastogne, losing 11 aircraft in the process. Later that morning, Eddy’s XII Corps attacked northeast of Luxembourg City, driving the Germans east of the Sûre River.

The surrounded, thinly stretched troops inside Bastogne fought off local German attacks and survived an artillery bombardment. The line was so thin that the men at one post joked, “How are you doing on your left?” “Good! We have two jeeps out there.” One of McAuliffe’s officers contacted an operations officer under Middleton, who’s VIII Corps commanded the 101st, and advised, “It’s getting pretty sticky around here,” adding, “The enemy has attacked all along the south and some tanks are through and running around in our area.” That night, McAuliffe sent a message to Gaffey: “Sorry I did not get to shake hands today. I was disappointed.” He sent a follow-up message that jabbed at Patton, who promised to relieve Bastogne on December 25: “There is only one more shopping day before Christmas.”

On the morning of December 24, Earnest’s CCA fought its way into Warnach, but the Germans counterattacked, fighting for most of the day until the Americans took the town before sundown. Dager’s CCB remained south of Chaumont, spending the day fighting off German counterattacks and exchanging artillery fire. Blanchard’s CCR encircled and finally captured Bigonville, effectively blocking any German attempts to cut off the 4th Armored’s base. Paul’s 26th Division soon replaced the tankers in Bigonville, leaving Blanchard to believe his men would get a rest until he received orders that night to head west.

As the Germans counterattacked all along Millikin’s front, Patton blamed himself, “This was probably my fault,” he wrote, “because I have been insisting on day and night attacks.” He felt the tactic worked when the Germans were surprised, but now he realized he was in error, using exhausted men against defended positions, especially when there was no guiding moonlight. “It takes a long time to learn war,” he confessed. While Gaffey’s men and tanks struggled to push north, Patton sent McAuliffe an optimistic message: “Xmas Eve present coming up. Hold on.” McAuliffe called Middleton and told him, “The finest Christmas present the 101st could get would be relief tomorrow.”

While the Germans pushed back against Millikin’s III Corps, Eddy’s XII Corps attacked a 17-mile-long line from Diekirch to Echternach and almost reached the Sûre River using Irwin’s 5th Division, elements of Major General William Morris’s 10th Armored, and Major General Raymond Barton’s 4th Infantry Divisions. When Patton learned that German prisoners admitted that they hadn’t eaten in three days and that his troops had intercepted a message from the German 5th Parachute Division that they could not hold on without help, he contacted his corps commanders about “this happy state.”

Patton felt the Germans had staked everything on this one offensive to restore the initiative, but it wouldn’t work. “They are far behind schedule and I believe beaten,” he wrote in his diary. “If this is true the whole army might surrender.” Yet, he knew the Germans had done it before in 1940, when they invaded France through Saarbrücken on Thionville. “They may repeat but with what?”

With all eyes on Millikin’s attack toward Bastogne, Patton wanted Eddy to continue pressing north. While Bastogne seemed like the obvious center of gravity, Patton knew that Eddy could choke off the German offensive at its base and possibly capture Trier. With that in mind, he declared to his staff, “[I] got two more regiments of engineers. That makes four. I want to use them in the Trier area.”

He also wanted his staff to provide Lieutenant General Omar Bradley, the commander of the 12th Army Group and Patton’s boss, with a situation report on Eddy’s offensive. “[The] future of this army depends on the impression we make regarding it. Be sure to emphasize the various danger spots—Trier, [our] exposed flank on the west, Echternach, and others.” Bradley visited, and the two reviewed the situation. Colonel Oscar Koch, Patton’s intelligence officer, briefed the two generals on Eddy’s situation and answered any questions.

Throughout the day, Patton wavered between confidence of the German collapse and worry about the pace of his army. He called General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme commander in Europe, expecting to be fired. When Eisenhower asked him where his worry came from, Patton responded, “I’m going too slow.” Eisenhower disagreed. “You’re going as fast as I expected. Keep it up, George.” Now in a much better mood, Patton visited Bradley’s headquarters. Major Chet Hanson, Bradley’s aide, found Patton “boisterous and noisy, feeling good in the middle of a fight.”

That evening, Patton paced the map room at his headquarters, chomping a cigar, worrying about his lack of replacements. Finally, he sat on the edge of his desk, staring intently at the map. “I wish I had another two divisions,” he told Robert Allen. “I could wipe them out.” Patton thought about the situation, then concluded: “The 101st is doing a great job. They [the Germans] can’t wipe them out. We can supply them now with this good weather and the Huns can’t overrun them. They are better men and better fighters than the Hun. If we can only have a few more days of good weather like today, then the war will be over.”

Patton then attended a late Christmas Eve mass at a small Episcopal church in the heart of Luxembourg City. He arrived late as the parishioners, mostly soldiers, sang the benediction. He stopped in the middle of the aisle and stared up at the main window, before sitting in the same pew where Kaiser Wilhelm II sat during World War I. Everyone recognized him. One witness said he looked “fierce and dramatic—as if he had come to demand God’s blessing for his sword.”

Christmas day dawned cold but with clear skies. “Lovely weather for killing Germans,” Patton wrote, “which seems a bit queer considering whose birthday it is.” The holy day energized him. At his morning briefing he declared, “Merry Christmas to you all! Here’s to hoping we spend the next one in Tokyo.” But his cheer turned serious as he listened to updates on his troops’ trek to Bastogne. Then he addressed the staff: “I want everyone to understand we are not fighting this battle in a half-assed way. It’s either whole hog or die. Shoot the works. If those Hun bastards can do it, so can we. If those sons-of-bitches want war to the raw, we’ll give it to them.”

Then it was back to work, with Patton shifting units and bringing more up to the line. He did not intervene when he learned that Millikin had attached two infantry battalions from McBride’s 80th to Gaffey’s infantry-depleted 4th Armored. He jotted down a quick message to Beatrice, telling her the three consecutive days of clear skies had helped him in the attack, but he vented, “so far, I am the only one attacking,” and concluded, “I am going out to push it now.”

Patton visited troops in both Millikin’s and Eddy’s corps. Along the way he crossed paths with a tank from the 702nd Tank Battalion heading south, away from the battlefield. He put his hand up and the tank stopped. The men climbed out to greet him. “Where are you going with this vehicle?” Patton asked. When the tanker commander told him they were taking it to ordnance he asked, “Do you think this vehicle should go to ordnance, don’t you think it will last a little longer?” The men assured him it would not.

Patton looked the tank commander up and down and suddenly turned deadly serious, asking the tank commander, “Where are your overshoes, soldier?” The commander replied that they had never received any. Patton told him, “I went through the hospitals, and I find a lot of frozen feet, and you can’t cure them. The Doughs [a World War I slang for infantrymen] that get hit with bullets or shrapnel can get well, but those boys in there that have frozen feet have no way of ever getting well. You’ll have overshoes here tonight.” He then asked the commander how far it was to the front line and climbed into his jeep, where his dog Willie waited, and drove away.

Patton visited all three of Gaffey’s combat commands, then Paul’s and McBride’s infantry. He found Gaffey’s tankers fighting hard but making incremental progress. Paul’s infantry made decent progress, but McBride’s men were stalled. “All, I feel, are doing their best,” he wrote. Earnest’s CCA, with an attachment from the 80th Division, had taken the town of Tintage, two miles west of Warnach, while the main force drove four miles north, reaching the high ground south of Hollange. Dager’s CCB spent the morning clearing the woods and plains around Chaumont with the help of its attached 80th Division units. The infantry then attacked into Chaumont, capturing it by nightfall. Blanchard’s CCR spent the day driving west. The Germans were threatening to capture the town of Sibret, on the southwest side of Bastogne, and Blanchard’s mission was to blunt them.

Patton visited Dager’s CCB, where he saw two American aircraft strafe and bomb the Germans, but to little effect. Then a few German fighters strafed the road where Patton stood, but no one was hit. Patton, having braved numerous air attacks in North Africa and Sicily, appreciated the historical milestone: “This is the only time in the fighting in Germany or France that I was actually picked out on the road and attacked by German air.”

Patton then visited Paul’s 26th Division headquarters. When he walked in, Paul felt sure his commander was about to fire him for his slow progress. Instead, Patton threw his arm around Paul’s shoulder and told him, “How’s my little fighting son-of-a-bitch?” Paul’s attitude changed, later writing, “I was so cheered for not getting relieved, there was nothing I wouldn’t have done for the man.”

In Eddy’s zone, Patton saw Irwin’s 5th Division which had driven the Germans back to the Sûre River and was threating to retake Echternach. Permission had finally been given to use proximity fuses, which enabled artillery shells to explode before hitting the ground, making them much more deadly. The infantrymen called them a “Christmas present, for the Germans.” Irwin’s artillerymen fired the new weapon from the hills overlooking Echternach, watching the shells explode over the Germans as they raced over a wooden bridge or paddled small boats across the Sûre. The fire became so deadly the Germans broke and ran back into the town. Patton put the German tally from the shells at 700 dead, but the Germans still held the town.

Overall, Patton was pleased to see his men were in good condition, cheerful, and eating at least one Christmas meal of turkey. He gave full credit to the Quartermaster Corps for providing rear-echelon soldiers hot turkey while the frontline soldiers at least received turkey sandwiches. “I know of no army in the world except the American which could have done such a thing.”

In Bastogne, there were no turkey sandwiches for the troops. Only K-rations and a scant hot meal, usually beans. Another aerial resupply had failed to get off the ground due bad weather in England. The Germans launched a major panzer attack into Bastogne from the west, but glidermen, paratroopers, and tank destroyers under Colonel Steve Chappuis stopped it. German tanks rolled over Chappuis’s paratroopers on a downhill slope to the town of Champs. The paratroopers suffered some casualties, but after the tanks passed the men stood up in their foxholes and cut down the enemy supporting infantry.

Paratroopers in the woods added to the fire, cutting down German infantrymen riding on the tanks. When the German tanks reached Champs, American tank destroyers and bazooka-wielding paratroops knocked them all out. It had been a major victory for McAuliffe’s command, but he did not share in his men’s joy. When a lieutenant reported on the German defeat, McAuliffe only shook his head and interrupted the young officer. “Hell, I know that! I want to know where the 4th Armored is.” He contacted Middleton and told him, “We have been let down.”

That night, Patton ate a late dinner with Bradley in Bradley’s mess hall. After dinner they talked about British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery, who now commanded Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges’s First Army on the northern side of the Bulge. Montgomery had supposedly declared that First Army was in no condition to go on the offensive for at least three months. Furthermore, he also said that Patton should pull back to the Saar line, or maybe the Moselle, to obtain more troops.

The plan did not sit well with Patton. “This is disgusting and might remove the valor of our Army and the confidence of our people,” he wrote in his diary. “If ordered to fall back I think I will ask to be relieved.” Eisenhower had actually gone to Montgomery’s headquarters that day to urge him to develop his own drive south to meet Patton’s. Montgomery, however, was convinced that another heavy attack was coming against him and wanted to hold off until the Germans were defeated. Eisenhower agreed to give him a few days to find a favorable moment.

The day after Christmas commenced overcast and cold. Patton spent the morning rearranging his forces. Eddy called with good news: Irwin’s soldiers had finally captured Echternach, obliterating the Bulge’s southern shoulder and ensuring the Germans could not ruin Millikin’s offensive. Even better, Irwin’s men reported entire enemy companies swimming the Sûre River under fire, which Patton considered “hardly a healthy pastime.”

While Eddy’s attack had yielded progress, Millikin’s attack seemed to yield only frustration. The Germans continued to successfully block all the routes to Bastogne. With his tanks stalled, Patton flew two medical teams via glider into the besieged town. The gliders came under fire but landed safely. By the afternoon, he admitted, “Today has been rather trying as in spite of all our efforts we have failed to make contact with the defenders of Bastogne.”

While Patton fumed about Bastogne, Gaffey’s 4th Armored tankers and infantrymen fought to get it for him. South of Bastogne’s perimeter, Blanchard’s CCR reached a crossroad at Remichampagne, only six miles from the heart of the town. Lieutenant Colonel Creighton Abrams, the commander of the 37th Tank Battalion, was preparing to head northwest to Sibret to protect the division’s left flank when he saw a flight of C-47s flying in supplies. The aircraft parachuted their cargoes to the beleaguered defenders as towed gliders released and soared down. Enemy antiaircraft fire hit some of the aircraft, dropping them out of the sky.

The sight of the brave fliers inspired Abrams. Realizing there was only one town, Assenois, between his force and Bastogne, he decided to try to do what the other combat commands failed to do: relieve Bastogne. He radioed up the chain of command until his request reached Gaffey, who called Patton around 4 p.m. and asked if he would authorize the risk to break through to Bastogne. “Go to it,” Patton said. Abrams would be racing against the Germans and the setting sun to break the ring around the town.

Before Abrams sent his tanks and halftracks north, he reviewed the situation with the lead tanker, Lieutenant Charles Boggess, telling him, “Get to those men in Bastogne.” Boggess’s tank roared north for Assenois, followed by tanks and halftracks carrying armored infantrymen. American artillery smashed into the small town at the base of a hill, but an enemy shell killed the artillery observer who was supposed to call off the barrage. The tanks drove directly into the artillery explosions. Some lost their way while halftracks stopped and their infantry dismounted to fight German infantry and paratroopers. Then a telephone pole fell on a halftrack further back in the column, blocking the road. Only three tanks, followed by a halftrack and two more tanks, made it out of the town. The artillery fire finally subsided when an American pilot flying over the battlefield realized what was happening and called it off. Abrams and some other tankers worked to wrestle the pole out of the way for vehicles to pass.

Patton’s entire drive to relieve Bastogne now consisted of five tanks and a halftrack. Boggess continued to lead the way, ordering his men not to stop but to fire into the woods on either side of the road as they went. The halftrack following the three lead tanks fell far enough behind that the Germans were able to throw a string of mines across the road. The halftrack hit one and exploded, causing the following two tanks to pull over and remove the other mines. Patton’s entire Third Army attack was now down to three tanks.

After more tense driving and firing, Boggess spotted a pillbox on the right side of the road and sent three 75mm rounds into it. His tank then slowed down as he spied the area. On his left, he saw two soldiers in American uniforms. He ordered the men to show themselves, explaining that he was with the 4th Armored. One of the men responded, “I’m Lieutenant Webster of the 326th Engineers, 101st Airborne Division, glad to see you.”

With that greeting, Bastogne was relieved. Gaffey called Patton again about three hours later and told him the good news. “It was a daring thing and well done,” Patton wrote. “Of course, they may be cut off, but I doubt it.” He immediately called Bradley and told him. Bradley had earlier heard from Major General Ernie Harmon, the commander of the 2nd Armored Division, who had reported stopping the German 2nd Panzer Division on the northern side of the Bulge. The entire German offensive, north and south, had been stopped. Bradley called General Walter Bedell Smith, Eisenhower’s chief of staff, and told him, “As near as we can tell, this other fellow has reached his high-water mark today.” Soon after, Patton received a note about the state of McAuliffe’s 101st: “Losses light/Morale high/Awaiting order to continue offensive.”

Reaching Bastogne proved a harsh campaign. Because of the snow and cold, the normal killed-to-wounded ratio flipped. Instead of suffering one dead to three wounded, Patton’s infantry suffered three dead to one wounded. Snow would quickly cover wounded men, causing medics to miss them, leaving them to freeze to death. Despite the losses and Patton’s constant complaining about his army’s slowness, he proudly declared in his diary, “The speed of our movements is amazing even to me [;] it must constantly surprise the Germans.”

Patton credited the breakthrough to Colonel Blanchard, the commander of CCR and Abrams’ commanding officer, whom Patton had served with at Fort Benning, Georgia. Still, he worried it might be a trap. “I hope that the troops making the advance don’t get bottled up too,” he wrote Beatrice. “My prayer seems to be working.” Three days later, he would write Beatrice again, declaring, “The relief of Bastogne is the most brilliant operation we have thus far performed,” adding, “Now the enemy must dance to our tune not we to his.”

Before Patton went to bed that night, he looked at the bigger picture of the campaign. While he spent the last four days shuffling troops to deliver the most strength where he thought they could make a difference, he blamed Eisenhower for not giving him any extra forces for the most important task of the campaign. Still, he considered the enemy spent. “The German has shot his wad,” he penned in his diary. “Prisoners have had no food for three to five days.”

Still, he should have been proud. The relief of Bastogne was Patton’s victory. While the 101st Airborne paratroopers and other tankers and soldiers from remnant units could pat each other on the back for having outlasted the German SS, armor, and infantry, it was Patton with his relentless attacks who broke the German bond on the vital crossroads town on the snowy hills of Belgium. But he had little time to celebrate his achievement. The campaign to erase the Bulge would be a much harder fight.

An editorial in the Washington Post summed up Patton’s success in the relief of Bastogne and on all his battlefields, likening him to America’s fireman. “It has become a sort of unwritten rule in this war that when there is a fire to be put out, it is Patton who jumps into his boots, slides down the pole, and starts rolling.”

While the editorial did delve into Patton’s troubled past, it credited him with repeatedly demonstrating, “…that when a jam develops, he is the one who is called upon to break it.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments