By Nathan N. Prefer

The term “United Nations” was in large part derived from the large number of nations that joined in common cause between 1939 and 1945 to defeat the Axis powers of Germany, Japan, and Italy during World War II. Scores of nations joined the major Allied powers to contribute, directly or indirectly, to the defeat of the common enemy. One of those nations was South America’s largest country, Brazil. Through the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, Brazil’s significant contribution of wealth, resources, and blood is, unfortunately, little remembered today. (Get a full look at the forgotten stories that shaped the twentieth century inside WWII History magazine.)

Latin America in World War II

Originally, Latin America was important to the United States for the resources it provided to a nation soon to be at war. In 1940, 90 percent of the region’s coffee, 83 percent of the sugar, 78 percent of the bauxite, 70 percent of the tungsten, as well as significant percentages of tin, copper, and crude oil were imported to the United States for both domestic and military consumption.

Although the United States was not yet at war, it had concerns about Latin America, for a dictator sympathetic to Adolf Hitler or Benito Mussolini might cause trouble for a United States that was trying to remain neutral. German propaganda took full advantage of the opportunity and distributed literature and films in Spanish to encourage dissension throughout Latin America. It even established a propaganda radio station in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Mexico was already at odds with the United States. It had expropriated American oil companies, and the United States was claiming that communist and National Socialist plots were prevalent throughout that country. And the Mexican government was ready to expel any American agents within its borders that were identified. Mexico also clearly anticipated a German victory, which the country was expected to use to strengthen its position with the United States. Mexico finally sent a squadron of fighter aircraft to the Pacific late in the war.

Other Central and South American countries such as Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, El Salvador, Peru, and Venezuela wanted no part of the conflict and remained on the sidelines.

Brazil’s Road to War

In Brazil in June 1940, President Getúlio Vargas had already informed the German ambassador that Brazil fully intended to maintain its independence, despite Vargas’s known dislike of the democratic system and the appeal he personally felt for totalitarian states. Other states, like Argentina, were split in their loyalties. Chile, Uruguay, and Panama (of the Spanish-speaking countries, only Panama entered into a declaration of war) were sympathetic to the American camp, but the United States had to bring the entire continent onto its side.

To do so, President Franklin Roosevelt established the Inter-American Financial and Economic Committee, based in Panama. Then a number of conferences were held in Panama, Rio de Janeiro, and Washington, D.C., to settle differences between the members. The Chapultepec Conference held in Mexico resulted in an agreement that laid the foundations of the future cooperation of the American states. With Nelson A. Rockefeller as his coordinator for inter-American affairs, President Roosevelt loaned the Latin American states money, increased imports from them to the United States, and sent American technicians to modernize the economy of the various countries.

The Germans did much to push Brazil into the American camp. U-boat attacks off the coast of Brazil sank several Brazilian ships and killed over 600 of its citizens, including women and children. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, President Vargas decided to honor his nation’s commitments to the United States and, in January 1942, broke diplomatic relations with Germany, Japan, and Italy.

The Brazilian Navy immediately took steps to protect its shipping while the air force conducted offshore patrols to detect enemy submarines. Several Brazilian military bases were ceded to the United States for similar uses. The sinking of Brazilian ships continued, however, with another dozen ships gone by August 1942. Vargas and his government had enough provocation by this point, and in the same month declared war on Germany and Italy.

The Creation of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force

It took longer for Brazil to decide how to contribute to the Allied war effort. Concerns that the fascist forces in North Africa, which bulged too close for comfort just across the South Atlantic, might take some aggressive action against Brazil, kept her forces at home in a protective mode. But with the Allied invasion of North Africa in November 1942 and the eventual defeat of the Axis forces there, Brazil turned to a more active role in the war.

On December 31, 1942, President Vargas announced in a speech that his government was beginning to “think on the responsibilities of an extra-continental action.” This idea would soon develop into the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, which would fight alongside the Allies in Italy in 1944 and 1945.

The first concrete steps were taken at a conference between Presidents Roosevelt and Vargas at Natal in northeastern Brazil on January 28, 1943. There the two heads of state agreed that Brazil would make some physical contribution to the Allied war effort beyond protecting its own borders. That March, President Vargas issued an “Explanation of Motives” written earlier by the war minister in which he proposed the organization of an expeditionary force to fight outside the continent. Thus was born the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, or BEF.

Although the idea had taken hold, there remained problems within Brazil itself. There were strong elements within the Vargas government who opposed Brazil’s participation in the war against the Axis powers. Then there was the problem of organizing, training, equipping, and staffing such a force. There was also a need to infuse into the Brazilian people a will to fight a war in the Old World, which was far away and often resented by factions of the populace. But Vargas and his followers began campaigns to overcome each of these obstacles in turn, and by the fall of 1943 he accomplished his goal. The BEF would consist largely of a single infantry division based on the contemporary American model. To create such a unit, existing Brazilian military units would be consolidated into the necessary combat formations. Thus, the three infantry regiments were formed from units spread across Brazil. The 1st Infantry Regiment, or Sampaio Regiment, came from the military district of Rio de Janeiro. The 6th Infantry Regiment, formerly the Ipiranga Regiment, came from São Paulo State. The 11th Infantry Regiment was formerly known as the Tiradentes Regiment and came from Minas Gerais State. Most of the artillery was formed from units then based in and around Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo.

The unit’s 9th Engineer Battalion came from Aquidauana, Mato Grosso State, while the Reconnaissance Squadron was formed out of the 2nd Mechanized Regiment, based within the city of Rio de Janeiro. The medical battalion consisted of units based in both Rio de Janeiro and São Paulo. On October 7, 1943, Maj. Gen. João Baptista Mascarenhas de Moraes was appointed to command the assembled units.

The general was born in São Gabriel, Rio Grande de Sul State, in 1883, and at age 16 entered the Rio Pardo Military School as a cadet. He then completed his military training at the Brazilian Military School in Rio de Janeiro and was commissioned a second lieutenant. Later in his career he won first place in the Officers’ Higher Training School and third place at the General Staff School; both courses were directed by the French military mission. He continued to rise in rank and responsibilities until he reached the highest post of chief of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force.

Adopting the American Military Model

For many years prior to the outbreak of World War II, the Brazilian military had been instructed by a French military mission. All of its military equipment was European. This ceased with the surrender of France in 1940. Now the Brazilian forces were to participate in a foreign war with different allies, and new tactics and techniques, not to mention organizational skills, had to be learned. To this end, General Mascarenhas traveled to the United States to quickly learn American military techniques, organization, and equipment.

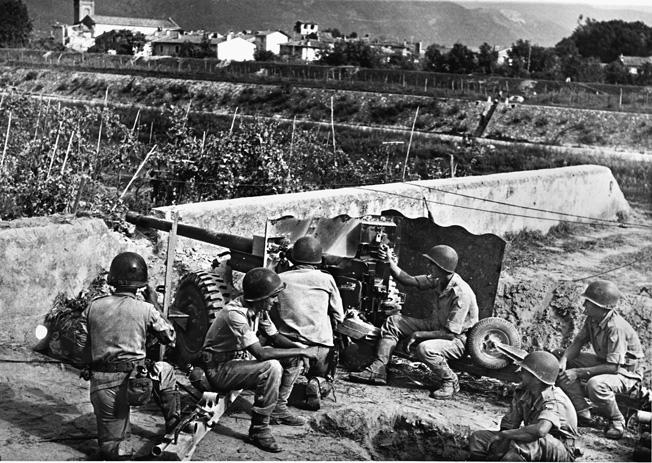

In Brazil the complete transformation of the BEF from a European-model organization to an American-based one took time and a great deal of effort. For example, the BEF had to be motorized, more specialists trained, and new equipment introduced. The M1 Garand rifle, the 60mm mortar, bazooka, .30-caliber light machine gun, 57mm antitank gun, and the 105mm artillery pieces, among others, were unknown to the Brazilians. These all had to be acquired, learned, and then implemented within the unit’s structure, which itself was changing.

Recruitment of personnel, particularly for the specialist positions, was difficult and time consuming. Additionally, many of its leading officers were still undergoing training in the United States. In December, General Mascarenhas traveled to Italy with a group of observers viewing the Italian campaign.

On December 28, 1943, Mascarenhas was officially named commander of the 1st Expeditionary Infantry Division (1st EID), and in January, upon his return from Italy, he assumed command of the still-forming BEF.

Meanwhile, the Brazilians were still struggling to convert from a French-oriented military organization to an American one. U.S. Army training manuals had to be translated, training methods adapted to U.S. standards, and the officers and men made physically ready for overseas deployment and the rigors of combat. This adaptation and training continued for many months, not unlike a U.S. division then training at home, and by April 1944 it became apparent that the BEF was being readied for overseas deployment. That deployment, in the greatest secrecy, began in late May 1944. In three separate groups, the 1st EID moved to embarkation points on the Brazilian coast and loaded into transports. Soon they were at sea in the Atlantic, bound for an unknown destination.

Arrival in Naples

It turned out that the destination was Naples, Italy, where the division assembled in mid-July 1944. Here the first group, commanded personally by Mascarenhas, was greeted by Lt. Gen. Jacob L. Devers, a commander of American troops in Italy.

Indeed, the Brazilians were probably more welcome than they knew. Italy had been the only area of operation for nearly a year until the Allies had, after a series of viciously difficult campaigns, finally captured Rome on June 4, 1944. But two days later, Italy became a secondary operation area as the main Allied forces landed in France at Normandy.

By July 1944, Allied commanders in Italy were in a desperate struggle to maintain their strength as forces were slowly but surely being drained away to northwestern Europe. In addition, another major landing on the southern French coast was scheduled for August, and some of the most experienced units and commanders in Italy were scheduled to depart for the operation. Thus the arrival of the fresh Brazilian Expeditionary Force with its 25,334 men was more than welcome.

The Brazilians immediately faced difficulties. The medical condition of many of the Brazilian troops was not up to standards, their uniforms were inadequate for the climate of Italy, and the general unpreparedness of the unit presented immediate problems. Despite the recommendations of the observer group (which had reported back that heavier and warmer clothing, sturdier boots, and other items were necessary to enable the combat troops to survive in the cold climate of mountainous central Italy), little had been done to make these available to the troops before their arrival at Naples.

The BEF and Mark Clark’s Fifth Army

Alerted to these problems by his personal inspection of his latest troops, Lt. Gen. Mark W. Clark, commanding the Fifth U.S. Army to which the Brazilians were assigned, took immediate steps to correct the deficiencies. Taking what the Brazilians needed from U.S. Army stocks, Clark equipped them sufficiently to allow them to participate in the coming battles.

More training was also on the agenda for the 1st EID. Although training facilities were few, the Brazilians used what was available and included sports, training marches, and sessions of close-order drill to acclimate themselves to their new surroundings. However, reports by inspecting U.S. medical authorities had some unflattering things to say about the physical condition of many of the Brazilian troops. Many suffered from easily preventable diseases while others suffered from dental problems which, once treated, would make the soldier ready for combat. These were all addressed immediately by the Brazilian command.

Relations between the Brazilians and Clark’s Fifth Army were good from the start. Having several other nationalities already under his command, Clark and his staff were used to dealing with unfamiliar methods, traditions, and customs. General Mascarenhas felt “the spontaneous and unanimous cordiality with which the U.S. officers at the headquarters in Cecina treated their Brazilian comrades was evident.”

But the Brazilians had not come to Italy to meet and greet new friends. They had come to fight and, after more training and updating of equipment, that is what Clark assigned them to do. With the loss of seven of his most veteran divisions to the invasion of southern France (Operation Dragoon), he needed combat units at the front to replace those veterans. In August 1944, Clark had available two new divisions—the 92nd U.S. Infantry Division (Colored) and Mascarenhas’s EID. Both of these he now sent to the front lines along the Arno River in northern Italy and into combat.

First Fight For the BEF

First to taste battle was the 1st Company, 9th Engineer Battalion, of the 1st EID under Captain Floriano Moller. Beginning on September 6, 1944, it was operating one of the bridges across the Arno River under the command of Maj. Gen. Willis D. Crittenberger’s U.S. IV Corps. Crittenberger attached two American tank companies and a communications platoon to the 1st EID, since the Brazilians had no armor of their own and communications with American units needed some sort of a liaison between the Brazilians and American headquarters.

Brigadier General Eurico Gaspar Dutra, in his position as Minister of War and representing the Brazilian government, took up a position as the liaison between the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, which included many supporting units outside the 1st EID plus reinforcement draftees to replace casualties, and Fifth Army to which the entire force was assigned.

When the first Brazilians arrived at the front lines, the Germans had been driven from the river and were retreating to their next major defensive line, the Gothic Line in northern Italy.

Assigned to the U.S. IV Corps on the left (west) of the Allied line, the BEF was to cover Route 64, a major highway leading into northern Italy through one of only a few passes in the high mountains of the region. The Brazilians were alongside the 1st U.S. Armored Division and the 6th South African Armored Division, along with a composite infantry group known as Task Force 45 made up of former American antiaircraft units converted hastily into infantry battalions.

The first combat assignment of the Brazilians was to replace American troops on the front lines. This they did on September 14, sending forward Colonel João Segadas Vianna’s 6th Infantry Regimental Combat Team and allowing the tired elements of the 370th Infantry Regiment and Task Force 45 to recuperate behind the front lines. Facing the Brazilians was the battle-hardened German XIV Corps, which had first begun fighting the Allies in Sicily more than a year ago.

Brazilian patrols quickly ascertained that the Germans had retreated from their front and, with authority from General Crittenberger, Major João Carlos Gross moved his 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry, up to the Monte Comunale-Il Monte line, followed swiftly by Major Abilio Cunha Pontes’s 2nd Battalion.

Soon, Captain Alberto Tavares da Silva had his 2nd Company, 6th Infantry, ride on American-supplied trucks into the towns of Massarosa and Bozzano, capturing the first towns in the Brazilian offensive. At 2:22 pm on September 16 the first rounds of Brazilian artillery were fired at the Germans by Captain Lobato’s battery of the Brazilian Field Artillery Group. Brazil was now in the war.

Victories at Camaiore and Monte Prano

But Mascarenhas was still anxious to try his troops against Germans who stood their ground. To do this, he planned an advance to a new line of operations around the area of Camaiore-Monte Prano. To reach this area the BEF would first have to capture Camaiore. Brig. Gen. Euclydes Zenobio da Costa, the division’s infantry commander, assigned a special mixed group under the command of Captain Ernani Ayrose of the 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment, to attack. This they did on September 18, supported by U.S. tanks.

But the tanks were halted by a destroyed bridge and Captain Ayrosa left them behind as his infantry continued the advance. Under intense artillery and mortar fire, the Brazilian infantry entered Camaiore and secured it against light opposition. First Lt. Paulo Nunes Leal was the first man into town, leading his combat engineers to clear German mines and booby traps. Close behind came the 7th Company under Captain Alvaro Felix, moving quickly in jeeps and trucks. Combined with other actions that day and the next by Major Abilio’s 2nd Battalion, 6th Infantry, the Brazilians were now facing the advanced positions of the vaunted Gothic Line.

Next on General Zenobio’s list was Monte Prano itself. From these heights the Brazilians would have better observation while denying the Germans the same advantage. A combined artillery, tank, and infantry attack was launched between September 21-26, and a series of violent patrol actions resulted in Lieutenant Mario Cabral de Vasconcellos reaching the peak with his patrol of the 6th Infantry Regiment. The entire action had cost the Brazilians five dead and 17 wounded.

The Serchio Valley

Soon after this first victory, the Brazilians were moved into the Serchio Valley to replace the 1st U.S. Armored Division, which in turn was transferred to another sector of the front. Still connecting the IV Corps front between the 92nd Infantry Division and Task Force 45, the Brazilian 3rd Battalion, 6th Infantry, under Major Silvino Nobrega, replaced the 3rd Battalion, 370th U.S. Infantry Regiment, while the rest of the 6th moved into position. Support in the form of the 2nd Battalion, 1st Self-Propelled Mortar Regiment, under Colonel Da Camino, followed immediately behind the infantry.

Skirmishing with the German 42nd Infantry Division began immediately. When heavy rains began on October 1, 1944, the Brazilian infantry, like those of all the combatants in Italy, were hampered by the wet, muddy, and difficult terrain.

Slowly the Brazilians maintained an advance into the Serchio Valley, capturing Fornaci and beating back a German counterattack. Intelligence gathered from patrols inspired General Zenobio da Costa to request permission of General Crittenberger to launch an attack to seize the Gallicano-Barga road. When permission was received, the Brazilians moved out and by October 11 had occupied Barga.

Gallicano was abandoned by the Germans, but the Brazilians were kept from occupying it due to the heavy artillery fire the Germans poured on the town. The Brazilians’ new positions dominated the road, which was their objective. Meanwhile, Colonel Jose Machado Lopes’s 9th Engineer Battalion worked on improving communications and supply routes behind the advancing BEF.

“The Snake is Angry”

During October, the Brazilian Minister of War, General Eurico Dutra, visited Italy and the Brazilian troops. In his tour he noted that the American and British troops all wore an emblem that differentiated them from each other. He inquired why the Brazilian troops had no such emblem, and General Mascarenhas gave Lt. Col. Aguinaldo Jose Senna Campos, his chief of staff, 4th Section, the job of creating an emblem for the Brazilian troops.

General Clark, the American commander, also expressed an interest in a unique Brazilian emblem. Taking the troops’ phrase “the snake is angry,” Lt. Col. Campos devised an insignia which quickly received the approval of the higher command. It depicted a coiled snake about to strike.

Patrols soon discovered that the enemy troops in front of the 1st EID had been replaced. The replacements were identified as Italian fascist troops of the Monte Rosa Division. Once again the Brazilians sought permission to attack. By the end of October 1944, the entire Brazilian Division was at or near the front lines.

Mascarenhas delayed the attack for a few days to allow the full supporting elements of the division to arrive. That attack, launched October 30, succeeded in securing all of the initial objectives and placing the Brazilians within four kilometers of the main enemy defenses of the Gothic Line.

The Germans objected to the close proximity of the Brazilians. At dawn on a rainy October 31, they counterattacked in strength. The Brazilians, surprised by the ferocity of the attack, were unprepared to meet it. Believing that they faced only weak Italian forces, they had relaxed their guard. As a result, several Brazilian units were forced to retreat and the Germans established footholds on two of the more recent Brazilian conquests, Hills 906 and 1048.

One Brazilian company of the 6th Infantry ran out of ammunition and was forced to retreat, while another found itself nearly encircled and managed to pull back only at the last possible moment. At a cost of 13 dead, 87 wounded, seven missing, and 183 non-battle casualties, the Brazilians had suffered their first reverse in Italy. But they had held their line with only limited withdrawals.

Recovering Combat Losses

Events elsewhere halted further operations for the immediate future. At a conference of commanders called by General Clark on October 29, General Mascarenhas learned that the American infantry divisions were exhausted, seriously short of infantry, and needed rest and reorganization before the offensive could be renewed. Alongside Fifth Army, the British Eighth Army was equally depleted.

To assist in refreshing the understrength units, the Brazilians would be asked to move once again, this time to relieve the 1st U.S. Armored Division and a part of the 6th South African Armored Division to allow them to move behind the lines to reorganize. For now the entire army group would go on the defensive. Plans were to renew the offensive in December once the assault troops had rested and been reinforced.

Pleased at being called a member of “the First Team” by General Clark, General Mascarenhas was soon busy moving his 1st EID’s infantry, artillery, and headquarters units to the Reno Valley area. Behind them the EID’s 1st and 11th Infantry Regiments continued to train, and General Zenobio da Costa returned to his position as Chief of Infantry to supervise the training, employing his recently gained experience to further enhance that training.

At the front, the 6th Infantry Regiment had to be split to maintain control of the Serchio Valley while other elements deployed to the Reno Valley area. Tanks of the 751st U.S. Tank Battalion were divided between the two groups. Company C of the 701st U.S. Tank Destroyer Battalion was also attached to the Brazilians. Actual command of the Serchio Valley sector passed to Maj. Gen. Edward M. Almond, commander of the 92nd U.S. Infantry Division. While waiting to transfer to the Reno Valley sector, the Brazilians incorporated about 50 Italian deserters into their own ranks to make up for combat losses which, up to October 31, had totaled 322, including 13 killed in action and seven missing.

Mascarenhas’s Controversial Decision

Beginning on November 2, the Brazilians were relieved in the Serchio Valley by elements of the 92nd Division. Over the next five days the advance Brazilian detachments moved into the Reno Valley and relieved the 1st U.S. Armored Division. Colonel Vianna of the 6th Infantry assumed command from Colonel Lawrence R. Dewey of the U.S. Combat Command in the valley. For the next three months the Brazilians would be defending the Reno Valley.

General Mascarenhas had some serious concerns with his assignment. First, he had to relieve the Americans immediately and therefore overruled the request of Major Gross to delay the deployment of his 1st Battalion, 6th Infantry, for a day to allow it to rest and replace needed equipment. Later this would become a matter of some controversy in postwar Brazil, but Mascarenhas’s decision was fully supported by letters from both General Crittenberger and Colonel Dewey.

Next, Mascarenhas was tasked with holding a divisional front with only one reinforced regimental combat team. His engineers were available as infantry, and his reconnaissance squadron was also available, but two of his infantry regiments were still training and being equipped behind the lines and therefore unavailable. His artillery was adequate, as was his communications company, but his experienced frontline troops were tired and under their authorized strength. Only time could rectify his situation, allowing his remaining units to complete training and equipping before joining the division at the front.

In the meantime, his orders from Fifth Army were “to continue the replacement of the U.S. 1st Armored Division, maintain contact with the South African 6th Armored Division (in position to the east of the Reno River), and be prepared to follow the enemy if he should retreat.”

The first two weeks of November were quiet in the Brazilian sector. On November 8, the 15th Army Group Commander, Field Marshal Sir Harold Alexander, came for lunch with Generals Crittenberger and Mascarenhas. Someone seems to have invited the Germans as well, for the high command group was subjected to a severe artillery barrage that they chose to ignore while finishing lunch. Field Marshal Alexander later jokingly thanked General Mascarenhas for the artillery barrage fired in his honor.

Meanwhile, behind the lines the equipping of the remaining infantry regiments continued to lag, and in fact never caught up with needs. Nevertheless, the 1st Infantry Regiment under Colonel Aquinaldo Caiado de Castro was moved up to the front on November 19 and was soon replacing the worn out and depleted 6th Infantry in the front lines. As was typical of German tactics, as soon as they learned of the new regiment’s arrival, counterattacks were launched to test the new men. The 1st Infantry held all its positions without difficulty.

Attack on Monte Castello

Nearby, Task Force 45 was assigned the mission of capturing additional ground as a prelude to renewing the offensive in December. Assigned to assist the attack were the 3rd Battalion, 6th Infantry Regiment, and the division’s Reconnaissance Squadron under Captain Flavio Franco Ferreira. Artillery support was provided by the 2nd Battalion, 1st Self-Propelled Mortar Regiment. Task Force 45 succeeded in the attack and was soon facing the German stronghold at Monte Belvedere that overlooked Highway 64. This initiated a major Brazilian attack against nearby Monte Castello.

Although the Brazilian division was without one-third of its authorized units, IV Corps ordered an attack against Monte Castello as another preliminary movement before resuming the full offensive. General Mascarenhas was now responsible for maintaining the defense of the Reno Valley, the offensive against the Monte Castello-Monte Della Torraccia (Hills 1027 and 1053) area, and seizing the town of Castelnuovo.

To accomplish these missions, he had no choice but to call to the front the remaining regiment of his division, Colonel Delmiro Pereira de Andrade’s 11th Infantry Regiment. Although incompletely trained and equipped, it was nevertheless necessary that it take its place at the front.

In fact, by early December the entire Fifth Army had been brought up to strength. Four American divisions in Maj. Gen. Geoffrey Keyes’s II Corps stood poised to renew the attack along Highway 65 to breach the German defenses of the Gothic Line. General Crittenberger’s job was “to maintain pressure against the enemy by continuing the series of limited objective operations initiated earlier by the Brazilians on the Bombiana-Marano sector.”

190 Casualties

Bad weather and lack of available close-air support caused the first in a series of delays that eventually continued over the winter. Later in December, when the Battle of the Bulge began in Belgium and Luxembourg, Field Marshal Alexander became concerned about a similar attack in Italy which would no doubt be aimed at the weaker of his two armies, the Fifth. He expected the attack to come in either the sector of the Brazilians or the nearby 92nd Infantry Division. The Fifth Army’s new commander, Maj. Gen. Lucian K. Truscott, Jr. (Clark was promoted to command of 15th Army Group), took immediate steps to place reserve units behind IV Corps.

Supported by the 13th Tank Battalion from the 1st Armored Division, and elements of the 751st Tank Battalion and 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion, the Brazilians launched their attack. Against an estimated battalion of German infantry, the attack on November 29 immediately ran into trouble when a German counterattack on nearby Monte Belvedere drove the Americans off the key hill and placed a strong enemy force on the Brazilian flank.

Deciding to renew the attack under cover of darkness, the Brazilian forces, led by the 1st Battalion, 1st Infantry Regiment, under Major Olivo Gondin de Uzeda, and 3rd Battalion, 11th Infantry, under Major Candido Alves da Silva, immediately faced steep terrain and determined resistance but continued slogging upward.

Covered by the artillery directed by Brig. Gen. Oswald Cordeiro de Faria, the advance went well until about noon when the enemy’s consistent heavy mortar, machine-gun, and artillery fire halted the attack. German counterattacks soon followed, and the exposed Brazilians had little choice but to retire. They suffered 190 casualties in the morning attack.

The Germans pursued what they perceived as an advantage and in the next few days counterattacked the Brazilians repeatedly. At one point Major Jacy Guimaraes’s 1st Battalion, 11th Infantry, was driven from its positions, but Major Silvino Castor da Nobrega’s 3rd Battalion, 6th Infantry, quickly regained the lost ground.

Disaster at Castello

With high command still determined to renew the major offensive before the new year, the Brazilians were given responsibility for the entire Monte Belvedere-Monte Della Torraccia hill mass. General Mascarenhas, with his infantry and artillery commanders and several staff officers, made a personal reconnaissance of the entire area to plan their next attack.

He decided that without sufficient men to maintain a 15-kilometer front and launch a major attack simultaneously that he would instead attack Castello and thereby isolate the Monte Belvedere-Monte Gorgolesco massif. Then, once supporting weapons had been moved forward, he would renew the attack on Belvedere itself. Heavy artillery fire was laid on the targets, and a diversionary group formed to distract the Germans. The main attack, to be launched on December 12 and led by General Zenobio, would be carried out by a strongly reinforced 1st Infantry Regiment.

Things could not have gone much worse. The attack began in a thick fog and light rain, and visibility was under 50 meters. Although some initial progress was made, strong enemy fire, mud, and terrain difficulties halted the attack by mid-afternoon. Another 140 Brazilians had become casualties with no gain to report.

Overall, the Brazilians lost 1,000 men in just over a day of intense combat. This failure was soon to be a point of contention between Brazilian and American leaders in the theater, but nothing serious came of it and relations continued amicably. It was also at this time that the high command in Italy came to the conclusion that nothing further could be accomplished during the Italian winter. All contingents were advised to go over to the defensive until spring.

Striking Into the Po River Valley

For the next 100 days, despite miserable weather conditions, the Brazilian division defended the mountains while awaiting better weather and orders to renew the advance. As early as February, plans for that advance were discussed by division and corps commanders. This time the Brazilians would be accompanied by another new American division, the 10th Mountain Division, under Maj. Gen. George P. Hays.

The Brazilians turned over the high mountains to the Americans, specially trained for mountain and winter warfare, while they would attack alongside, again against Monte Castello. Coordinating its attack with Hays’s mountaineers, the 1st EID struck again on February 21, 1945, supported for the first time by Brazilian-manned aircraft.

This time battalions of the 1st and 11th Infantry Regiments attacked and, after a fierce struggle, succeeded in taking Monte Castello just as Belvedere fell to the neighboring Americans. Congratulations quickly poured in from Generals Clark, Truscott, Crittenberger, and others. The last major line of German defenses before the Po River Valley had been broken.

The Brazilians had at last proved themselves in a major operation and would be used again by Fifth Army. They relieved the 10th Mountain Division on Monte Belvedere and later fought at La Serra, Castelnuovo, the Marano Valley, and the Panaro Valley, and in the spring offensive (Operation Craftsman) that quickly turned into a pursuit of retreating German forces.

General Crittenberger sent his 34th U.S. Infantry Division and the 1st EID northwest along Highway 9 to seal off the German LI Mountain Corps and its three divisions, followed nearby by the 92nd Infantry Division. By this time, April 23, 1945, the strong defenses of the northern Apennines were far behind and the Germans, weak, disorganized, and defeated, were on the run.

Soon, IV Corps, including the Brazilian division, were in the Po Valley cleaning up lingering German resistance and assembling thousands of surrendering German soldiers. With the 34th Infantry Division on its right, the 1st Brazilian Infantry Division led the way up Highway 9, closely supported by the 1st Armored Division. By April 29, the Brazilians had forced the surrender of significant elements of the German Fourteenth Army, including the 148th Infantry Division, elements of the 90th Panzergrenadier Division, and an Italian fascist division. The full capitulation was only days away.

That same day, April 29, the Brazilians were alerted to move to Turin and Alessandria to take on the German LXXV Corps, which was reportedly moving from the Franco-Italian border toward the advancing Fifth Army. This strong force was the only serious remaining enemy threat left in northern Italy. To meet it, three BEF combat teams were formed (Combat Teams 1, 6, and 11). The Brazilians made good progress, and Combat Team 11, commanded by Brig. Gen. Eyxlydes Zenobio da Costa, soon had Alessandria under control. Combat Team 6, under Brig. Gen. Falconié da Cunha, sent out patrols looking for the reported Germans but could find none. It would turn out that, harassed by the French Army and pro-Allied Italian guerrilla forces, the reported German advance had been turned back. Two days later, on May 2, 1945, the Germans in Italy surrendered.

20,000 Enemy Soldiers Captured

The Brazilian Expeditionary Force (including the Brazilian Air Force, which included the 1st Fighter Group and an observation and liaison squadron) had accomplished its missions. The BEF had captured more than 20,000 enemy soldiers and killed thousands of others at a cost to themselves of 88 killed, 10 missing, 486 wounded, and 252 noncombat injuries, for an April 1945 battle casualty total of 836.

The full campaign in Italy had cost Brazil 454 dead, including 14 unknown, plus eight air force officers. Two others were missing and presumed dead, and one body was never recovered. Thus the total cost to Brazil for its participation on the Allied side in Italy was 465 dead or missing.

On other fronts the Brazilians had contributed three destroyer escorts to protection of merchant traffic in the Atlantic, escorting 2,981 merchant ships in 251 convoys carrying over 14 million tons of supplies to the fighting forces. No ship escorted by the Brazilian Navy was lost to enemy action during the war. Its own merchant marine suffered the loss of 31 ships sunk and 969 crew members killed.

After the war Maj. Gen. João Baptista Mascarenhas de Moraes would be promoted to the title of Marshal of the Army and held that post until his death in 1968 at the age of 84.

By June 25, 1945, the Brazilian Expeditionary Force was assembled in Francolise, Italy, awaiting shipment home. One group, known as Task Force Italy, would remain to assist in the occupation of the country, but the majority of the troops would depart for Brazil as they had come—in echelons depending upon the length of their overseas service and the needs of the military.

Back at home the War Ministry issued Order 217-185, dated July 6, 1945, which decreed that as each echelon returned home it would be subordinated to the 1st Military Region, effectively disbanding the Brazilian Expeditionary Force. Stopping only once at Livorno to pick up the wives of Brazilian soldiers who had married while in Italy, the Brazilian Expeditionary Force sailed home and into history.

The correct phrase in a 105mm howitzer round inscribed with the troops’ message for Hitler in Portuguese is : “The snake is smoking”.