By Eric Niderost

On October 27, 1937, the Zhabei district of Shanghai began to burn, an enormous conflagration that stretched for five miles and filled the northern horizon from end to end, almost as far as the eye could see. The orange-yellow flames greedily consumed buildings and their contents, finishing the destruction already begun after three months of intense fighting between the Chinese and Japanese armies. Thick coils of smoke reached 3,000 feet into the air, obscuring the skies of central China. It was a spectacle never to be forgotten by those who witnessed it—the funeral pyre of a great city.

Some of the fires came from the fighting, but most had been deliberately set to cover the Chinese Army’s retreat. The outnumbered Chinese had resisted gallantly, but many units now were reduced to mere shadows of themselves. When word came that the Japanese had gained ground outside the city and were threatening the Chinese flank, there was no other choice but to withdraw.

One unit was deliberately left behind, entrenched around a concrete warehouse just opposite the International Settlement. The officers and men of the 524th Regiment, 88th Division, knew only too well that their mission was suicidal, that they were being sacrificed to showcase Chinese courage, but they accepted their fate stoically. Their ordeal, which had started on October 26, would continue for another four days of brutal fighting, and the defense of Sihang Warehouse would rivet the attention of the world, with the American press quickly dubbing it “the Chinese Alamo.”

The Impromptu Sino-Japanese War of 1937

The Sino-Japanese War of 1937 had begun in a haphazard manner. Throughout the 1930s the Japanese military, imbued with an aggressive “samurai” spirit and rabid ultra nationalism, gained the upper hand in Japanese politics. In 1932 the Japanese seized Manchuria, China’s rich northern province, and set up an “independent” government under the last emperor of China, Henry Pu Yi. It was a transparent ploy, mere window dressing to cover naked aggression, and few nations in the world community were fooled by it. The major powers, however, particularly Great Britain and the United States, were too preoccupied by the deepening economic depression to do more than lodge a few feeble and ultimately ineffectual protests.

China was in turmoil in the 1930s, torn asunder by Japanese aggression from without and internal dissension from within. The country was ruled by the Nationalist Party under Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek. Chiang was a pragmatic soldier-politician whose main obsession was the destruction of the Communists under Mao Zedong. To Chiang, Mao and his followers were like a deadly disease infecting the Chinese body politic. Chiang’s Communist preoccupation was a godsend to Japanese militarists. After 1932 there was a series of incidents between the Chinese and Japanese, with the Chinese usually granting concessions and territory to the aggressors. Having digested Manchuria, Japan was still ravenous, nibbling away at the rest of China throughout the decade.

On July 7, 1937, a Japanese soldier went missing near Beijing. Eventually, the soldier returned unharmed (reports said he had been visiting a brothel). But local Japanese officers, always ready to find a pretext for open aggression, demanded restitution for the alleged kidnapping. If the usual pattern had held true, the Chinese would have granted more concessions, territory, or whatever else the Japanese wanted. But this time the Chinese flatly refused—a line had been drawn in the sand.

Intense fighting between the two sides broke out and quickly escalated into a major conflict. The Japanese soon occupied Beijing and large parts of northern China. The 1937 war was entirely unplanned, but, once begun, the Japanese were confident it would be a quick one. They hoped so. More than anything, the Japanese military did not want to be drawn south, because just across China’s northern borders lay the Soviet Union, which the Japanese rightly considered a deadly enemy.

The Generalissimo’s Army

Chiang Kai-shek had other plans. The great Yangtze River of central China nourished the heartland of the nation and the center of its developing economy. China’s economic and political capitals, Shanghai and Nanking, were located there. Chinese troops in Shanghai had fought the Japanese to a standstill in 1932; Chiang had every reason to believe he could repeat their performance. As a first step, he began pouring troops into Shanghai, including the crack 87th and 88th Divisions. German equipped and trained—they even wore the distinctive steel helmets soon to be familiar in World War II—the Chinese troops were elite forces who proudly bore the title, “the Generalissimo’s Own.”

The Chinese Nationalist Army—formally titled the National Revolutionary Army of the Republic of China—was a juggernaut on paper, boasting some 1.7 million men. Unfortunately, the bulk of the Chinese Army was made up of of semi-illiterate peasants who were poorly uniformed, trained, and equipped. Only around 300,000 men, some 40 divisions, were sufficiently equipped and trained to have a fighting chance against the ramrod-stiff Japanese Army. Of these, some 80,000 were members of the Generalissimo’s Own.

In the mid-1930s, Shanghai was the richest, most progressive, and most decadent city in Asia. The city’s core was dominated by foreigners, a legacy of China’s troubled past. The International Settlement was ruled by a British-dominated Municipal Council, hard-headed businessmen whose primary interest lay in making a profit. The nearby French Concession was ruled as an out-and-out colonial possession of France and generally conveyed a kind of Gallic aloofness. Greater Shanghai was ruled by Chiang’s central government. When the war broke out, it was Greater Shanghai that was to see the bulk of the fighting.

The International Settlement figured prominently in Chiang’s overall plans. The Chinese could attack the Japanese garrison at Shanghai’s Honkou district, which was small and vulnerable. A success at the Settlement’s very doorstep would underscore China’s strength and resolution in the face of Japanese aggression. There was even the possibility that the western powers, particularly Great Britain and the United States, would intervene on China’s behalf. Accordingly, Chiang began pouring troops into the Shanghai region, including the elite 87th and 88th Divisions. Soon, there were upward of 50,000 Chinese soldiers in position. Consternation reined in the Japanese high command; they had no wish to be drawn into central China when northern operations were still in full swing. But the Chinese, as Chiang intended, had forced their hand.

The Battle of Shanghai

On August 12, Colonel Charles F.B. Price of the U.S. 4th Marine Regiment conferred with American Consul-General Clarence Gauss and British Brig. Gen. Alexander Telfer-Smollett about the looming Shanghai crisis. At the same time, the Shanghai Municipal Council mobilized the Shanghai Volunteer Corps and formally requested support from the British and American garrisons. Under a long-standing arrangement, code-named Plan A, British troops from the Shanghai Area Force and American marines would man a defensive perimeter along the Settlement’s borders. The Suzhou Creek border was of particular concern, because Zhabei, the Chinese district just beyond, had been the scene of brief but bloody fighting in 1932. Because the water table was only a foot or two below Shanghai streets, trenches could not be dug, and millions of sandbags had to be trucked into the area. Barbed wire was strung and sandbags stacked to form blockhouses, walls, and machine-gun emplacements. As marines and tommies moved into position, thousands of Chinese civilians poured over the bridges spanning Suzhou Creek, seeking refuge from the inevitable clash. Once the perimeter was manned, it was simply a matter of watching and waiting for the Japanese to appear.

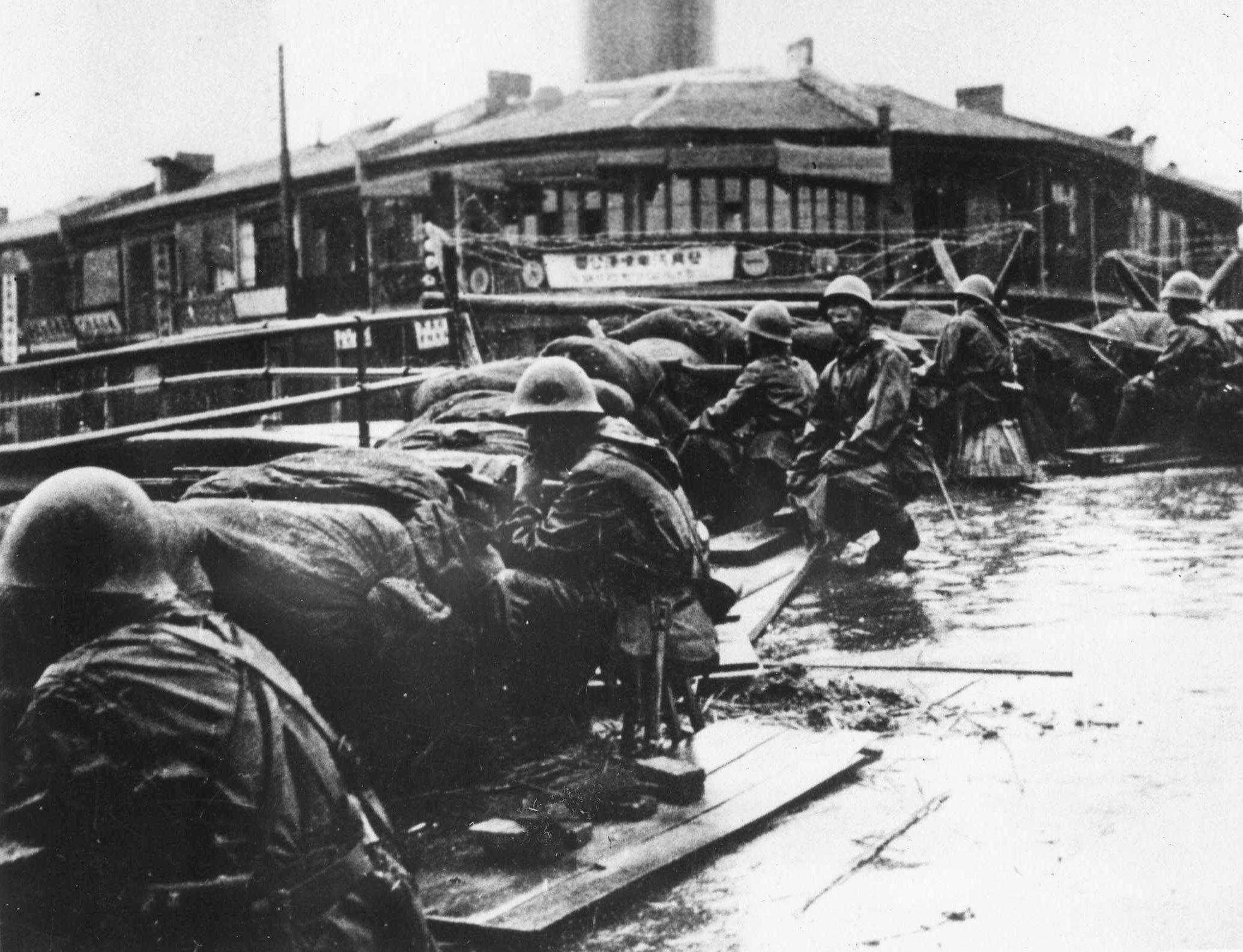

The wait proved to be a short one. Around 9 am on August 13, Chinese troops exchanged small-arms fire with Japanese units. The Japanese responded in kind, and the Chinese 88th Division retaliated with heavy mortar attacks. Japanese Admiral Kioshi Hasegawa’s Third Fleet vessels, which were on station in the Yangtze and Whangpoo Rivers, opened up with thunderous salvos. The Battle of Shanghai had begun.

On August 14, the Chinese began a major offensive, an attack that was designed to push the Japanese into the Whangpoo River. They almost succeeded. The outnumbered Japanese were mainly bluejackets and marines from the Special Naval Landing Force. It seemed as if the modern-day samurai were about to be humiliated at the hands of the despised Chinese. To be defeated in battle, and to have that defeat witnessed by the Western powers, was too much for the Japanese to bear. Soon, massive help was on the way. The Shanghai Expeditionary Army, under General Iwane Matsui, was assembled and sent to China immediately. It was a powerful force, built around the 3rd and 11th Divisions and totaling some 300,000 men, 300 guns, 200 aircraft, and the powerful presence of the Japanese Imperial Navy. The expeditionary forces made successful amphibious landings along the northeast coast at Boashan and elsewhere, and in so doing lengthened the battlefront. It now extended from Shanghai’s city center, down the length of the Whangpoo, finally ending at the northeast coast area where the river emptied into the mighty Yangtze.

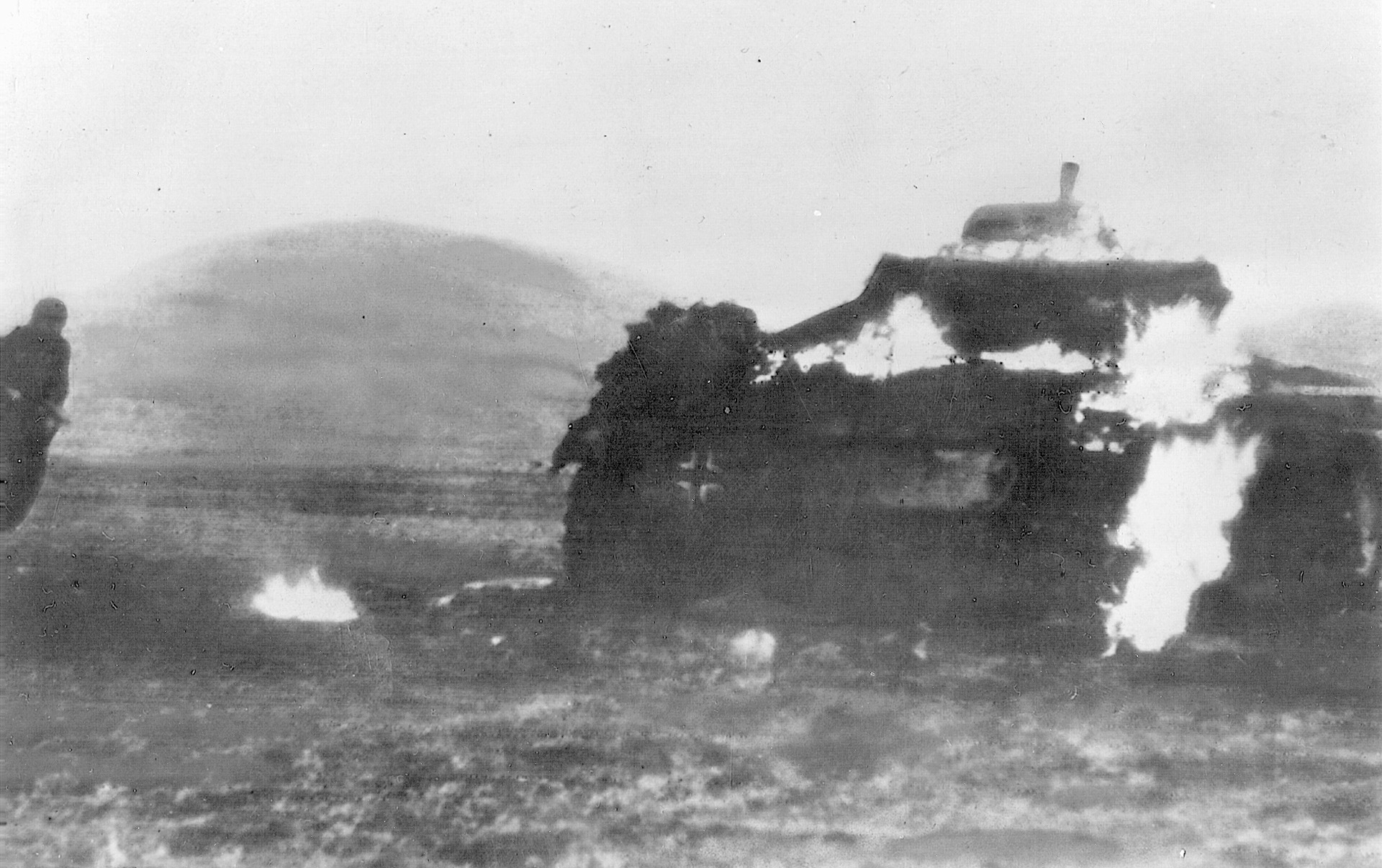

The newly landed expeditionary force tipped the balance in favor of the Japanese. Because the battle front had widened, Chiang was forced to send troops to other locations. The Chinese offensive, poised on the very brink of success, ground to a halt. Superior Japanese weaponry also began to make itself felt, particularly artillery fire, tanks, and aerial bombardment. Ten Chinese soldiers died for every Japanese, but the Chinese refused to be broken. For some units, casualty rates of 1,000 an hour were not uncommon.

A War “Between Races”

The battle for Shanghai became a slaughterhouse, a stalemate that conjured memories of Verdun and the Somme. ”It was no longer,” a witness said, “a war between armies, but between races. With mounting fury the two giants sprang at each other’s throat.” The Chinese held out for the next three months, and the fighting was particularly heavy at Zhabei, just across from the International Settlement. The Settlement was a kind of neutral zone, where foreign reporters could observe the battle from relative safety. American journalist Emily Hahn and friends would go to the tower room atop the Cathay Hotel and watch the battle while sipping cocktails before dinner. Others congregated atop the Park Hotel and other such establishments, viewing the spectacle as if it were some Fourth of July pageant staged for their benefit.

Guests were warned not to go onto hotel roofs because shrapnel and bomb fragments were always peppering the air. Since the Chinese still held Nantao, on the other side of the Settlement and the French Concession, Japanese artillery would risk an international incident by arcing shells over the foreign-held area, a distance of some four miles. Settlement residents became inured to the once-frightening sound of shells going over their roofs, which one woman likened to the sounds of a freight train.

By the end of October, the Chinese Army was being bled white, but the stalemate continued. The Japanese concentrated their effort at Dachang, a little village six miles northwest of Shanghai proper and a key point in the Chinese line. Some 700 Japanese artillery pieces opened up, followed by massive air raids by 150 bombers. Smashed beyond recognition, the little “chicken village,” so named because it supplied much of Shanghai’s poultry needs, fell to the enemy on October 25.

Fortifying the Chinese Mint Godown

Once there was a breach in the defense line, the Chinese flank was exposed. There was nothing to do but retreat in good order, withdrawing behind the south bank of Suzchou Creek as rapidly as possible. That meant abandoning the positions in Zhabei that had been held at such a huge cost in blood and treasure. Whole sections of the Zhabei district were in ruins, and shell-cratered streets and skeletal buildings reeked with the stench of smoke, cordite, and decomposing bodies.

Chiang Kai-shek was a realist, but he was loath to abandon Shanghai. He knew that a Nine-Power Conference was going to convene in Brussels on November 6, and he still retained hope that Western interests would intervene. China had to show that it was worthy of help, so another sacrifice must be made. A rear guard would hold out as long as possible, simultaneously demonstrating Chinese courage and buying time for the main army to escape.

His mind made up, Chiang ordered General Gu Zhutong to leave the 88th Division behind as a rear guard. Gu thought this was a terrible waste of one of China’s best units, which already was decimated by three months of fighting. Nor did General Sun Yuanliang, the 88th’s commander, want to see the whole division sacrificed on the altar of political expediency. It was finally agreed that a single regiment of the 88th would be left behind, while the rest of the division would be allowed to retire and regroup.

The forlorn task was given to the 524th Regiment, which was posted near some of the heaviest fighting at the North Railway Station. Lt. Col. Xie Jinyuan volunteered to command the regiment in its suicidal mission. After some hurried consultations, it was decided that Sihang Warehouse would be the spot where the 524th’s last stand would take place. This was a six-story warehouse that had been a joint venture by four banks (in Chinese “Sihang” means “Four Banks”). Westerners knew the place as the Chinese Mint Godown.

It was an ugly, strictly utilitarian structure, but its thick, reinforced concrete walls were perfect for defense. The warehouse was literally on the edge of Suzchou Creek, the meandering waterway that separated Chinese Shanghai from the foreign-controlled International Settlement. British troops sheltering behind their sandbagged defenses had a grandstand seat for the coming battle. The warehouse was on Tibet Road, which continued on into the International Settlement across the New Lese Bridge that spanned Suzchou Creek.

Xie placed his troops with care. Makeshift fortifications were created just outside the warehouse building, consisting mainly of sandbags and sacks of corn, beans, and other goods that had been stored there. First Company took up positions on the left, along Tibet Road, while Third Company was stationed on the road to the right, just opposite the Bank of Communications building. Second Company fanned out to protect the warehouse’s other three sides. Two heavy machine guns were placed on the roof, and other machine guns were distributed among the defenders on the ground.

The Japanese Launch Their First Assaults

When the Japanese realized the enemy was in full retreat, they cautiously probed forward. By 1 pm on October 27, advance elements were approaching the vicinity of the warehouse. After some preliminary exchange of fire, a Japanese company attacked the warehouse from the west. They were met by determined resistance from Third Company. At one point, some 70 Japanese soldiers took shelter in a blind spot just to the southwest. It was indeed a blind spot—but only to defenders on the ground. Chinese soldiers on the roof spotted the cluster of Japanese and lobbed grenades down on their heads. Seven Japanese soldiers were killed and another 20 wounded from this deadly “rain.” Captain Shi Meihao, commander of Third Company, was shot in the face during the fighting, but refused to relinquish command. Although blood was coursing down his face and soaking his uniform, he refused to withdraw until he was wounded again, this time in the leg.

The first Japanese assault was a failure, but before calling it a day, they set fire to the northwest corner of the warehouse; the defenders managed to put out the flames. About 9 pm, Xie, believing there would be no more Japanese attacks, ordered the men to cook dinner and repair fortifications. Two defenders had been killed and four wounded, while Japanese losses had been about 20 killed and an unknown number of wounded. The Sihang defenders faced the Japanese 3rd Division, considered one of the best of the Imperial Japanese Army. They also had mortar teams, artillery, and armor—probably Type 94 Te-Ke tankettes. The battle on October 27 was just an overture to the coming symphony of destruction.

The morning of October 28 saw the skies filled with the steady drone of aircraft engines—Japanese bombers flew overhead, but after a couple of aborted passes they were forced to return to their base. Sihang Warehouse was simply too near the International Settlement to risk full-scale bombing. The last thing the Japanese wanted was to blow up Western observers and cause an international incident. The Japanese also wanted to use mustard gas, but they were being watched too closely by Western newsmen and British soldiers to get away with it.

At 8 am, Xie inspected the defenses and gave impromptu pep talks to his men. It was during one such roof inspection tour that a party of Japanese soldiers was seen creeping along Suzhou Creek. Xie interrupted his speech, grabbed a rifle, and took aim at one of the distant enemy soldiers. Drawing a bead, he pulled the trigger with a steady hand. A second later, a Japanese soldier fell into the rubble.

The Japanese occupied the Bank of Communications building and launched a heavy assault on the west side. Chinese rifle and machine-gun fire sprayed lead into the oncoming brown-uniformed masses, but they refused to yield. The attack finally broke off after two hours. The Japanese had gained little, but did manage to cut off the warehouse’s water and electricity.

The warehouse was now flanked on three sides, but the fourth side—the side that faced Suzchou Creek and the British Royal Fusiliers’ positions in the Settlement—was left conspicuously open. The British also kept the New Lese Bridge open, which was a possible escape route for the beleaguered defenders. When Japanese soldiers tried to creep in on the fourth side, British tommies on the opposite bank trained their Lee-Enfield rifles at them. The Japanese got the message; they withdrew, and the fourth side remained open.

The “Lost Battalion”

Normally there were over 1 million Chinese residents in the International Settlement, but their numbers had been swollen by hundreds of thousands of refugees. News of the heroic last stand was spread by radio reports and word of mouth. Soon, thousands of ordinary Chinese citizens, protected by the Settlement’s neutrality, could watch the battle unfold before their eyes. It became a kind of bizarre sporting event, with Chinese spectators crowding Suzchou Creek’s banks to cheer on the defenders. At times an estimated 30,000 Chinese joined British soldiers and other Westerners to watch the show. When the crowds saw a Japanese movement, they would pass on the information to the defenders via enormous message signs in characters large enough to be read from a distance.

Whenever the Japanese had a setback or the defenders gained a temporary upper hand, loud cheers would erupt from the watching crowds. But support was more than visual. More than 10 truckloads of supplies were donated to help the men besieged in the warehouse. Food, fruit, clothing, utensils, and even personal letters were delivered under cover of night. Xie also arranged with British officers to evacuate the wounded to the safety of the International Settlement.

Earlier, a teenaged girl guide named Yang Huimin had been instrumental in passing messages back and forth between the besieged warehouse garrison and the Shanghai Chamber of Commerce in the Settlement. On the evening of October 28-29, the brave young woman brought over a national flag, emblem of the Chinese Republic. Because there was no flagpole, two bamboo poles were lashed together for the purpose. The red-and-blue banner was hoisted into place atop the roof, while thousands of Chinese spectators across the creek cheered and shouted, “Long Live the Chinese Republic!”

The battle for Sihang Warehouse was fought on two fronts—on the battlefield and in the court of public opinion. It was clear that the Japanese were losing, even as they made gains elsewhere. Foreign journalists, scenting a good story, flocked to Sihang Warehouse to report every detail. The press romantically dubbed the 524th Regiment the “Lost Battalion.”

At one point, Xie was asked to produce a list of every man in the garrison. In that way, should they fall, their names would be remembered. But Xie feared the information would eventually fall into Japanese hands. The wily colonel gave out a regimental roster that dated from the beginning of the war, when the regiment numbered some 800 effectives. In reality, the Sihang Warehouse was defended by only 411 men, including 16 officers.

When Japanese Admiral Tadeo Honda was interviewed by foreign newsmen, he grudgingly called the defenders “more or less heroes.” Oddly enough, all the phone lines into the warehouse remained intact, and defenders could call out at any time. The Japanese issued an ultimatum: surrender or be wiped out. Xie was unimpressed. In a message to his superior, General Sun, he radioed defiantly: “Death is an unimportant question. The sacrifice of our lives will not be in vain.”

“They Must Die That China Can Live”

Infuriated by the continued resistance and particularly the flag-raising ceremony, the Japanese set October 29 as the day for an all-out assault. The eyes of the world were upon them, and they were losing face. They opened with a heavy barrage of light artillery, exploding shell after shell against the warehouse’s concrete sides. Soon, ugly craters appeared on the walls, smudged and blackened with smoke and jagged with twisted reinforcing rods. Concrete rubble was everywhere, and the air was heavy with the stench of cordite and dust.

The west side of the building lacked windows, but Japanese shell hits had punched enough gaps into the wall to provide the defenders with loopholes. The Japanese, acting in concert with infantry, then brought forward tankettes. The fighting grew so heavy the Chinese Third Company was pushed back from its position and forced into the warehouse. Japanese infantry came forward with scaling ladders, a curious throwback in an age of mechanized war. The Chinese simply pushed the ladders off or peppered the advancing enemy with rifle and machine-gun fire. Xie personally lent a hand, fighting alongside his men. The Japanese seemed on the brink of success. Desperate times called for desperate measures, and one Chinese defender wrapped grenades around his body and jumped into the midst of a group of Japanese soldiers, detonating the grenades and killing himself and 20 of the enemy. The Japanese attack was beaten back.

The Sihang defenders’ morale was high, but the foreign observers in the Settlement had had enough. Misaimed bullets and shell fragments were falling in their midst, and with the battle escalating by the hour, it was feared that the fighting would spill over into the International Settlement. The British offered to broker a peaceful settlement that would end the warehouse siege. General Telfer-Smollett was a key player in the delicate negotiations, but he found his proposals a tough sell. The Chinese flatly refused to withdraw the men. Madame Chiang Kai-shek, American-educated and a power within the Chinese government, said coolly, “They must die that China can live.” The “victory or death” rhetoric surprised and dismayed Western observers.

The battle opened again in the early morning hours of October 30. This time the Japanese were not about to squander precious infantry in a headlong frontal assault—they were going to pound the “lost battalion” into submission with artillery. Japanese batteries opened up about 7 am and continued to fire throughout the day. At its greatest intensity, shells were coming literally every second, producing a cacophony that shattered the nerves and numbed the eardrums. Night fell, but the artillery barrage continued without letup. Japanese searchlights stabbed the sky, the probing beams fixing the battered warehouse to provide gunners a better target. The defenders grimly held on, helped by the thick concrete walls and the Japanese reluctance to use heavy artillery or bombs.

Withdrawal Under British Covering Fire

Behind the scenes, Telfer-Smollett was still trying to convince Chiang Kai-shek to let the men retreat from Sihang Warehouse. The Generalissimo finally consented. The main Chinese Army already had successfully withdrawn, and the heroic stand had amply demonstrated Chinese courage to the world. There was no need to fight to the last man. The Japanese commander, General Matsui, agreed to the developing deal, which would allow the Sihang men to retreat into the International Settlement via the New Lese Bridge. There was to be a truce and cease-fire during the withdrawal, which was to start at midnight on November 1.

The subsequent withdrawal was marred by bad faith on the part of the Japanese. As the Sihang men left the warehouse and crossed the bridge, the Japanese suddenly opened up with machine-gun fire and artillery, raking the bridge with a hail of lead and forcing the Chinese to run through a gauntlet of fire. This was too much for the Royal Fusiliers, who manned a sandbagged pillbox that anchored and protected the Settlement side of the bridge. The British tommies were emotionally on the Chinese side, and were also tired of taking misguided Japanese fire without a chance to defend themselves. Four British soldiers had already been killed and another six wounded by stray Japanese bullets.

The British pillbox gave the Chinese covering fire, although this was strictly against orders and violated the Settlement’s official neutrality. A Japanese machine gun was put out of action by British bullets, and Xie and 376 of his men managed to escape successfully. Telfer-Smollett had been sheltering behind the Chinese Bank during the withdrawal; he now greeted the heroes as they crossed over into the Settlement. Xie was the last to leave the warehouse and the last to cross the bridge into safety. Tears coursed down his cheeks as he accepted accolades from the British soldiers. He had not wanted to leave at all, and only did so under orders. Telfer-Smollett, overcome with emotion, exclaimed, “I have never seen anything greater!”

Political Fallout of the “Lost Battalion”

Cheated of their prey, the Japanese quickly reneged on the agreement. The “lost battalion” would absolutely not be allowed to retreat though the Settlement and rejoin the main Chinese Army. The Japanese would only consent if the solders left as refugees, abandoning all weapons, including the light and heavy machine guns they had brought with them. Xie flatly refused. Instead, battalion members were forcibly disarmed and interned by the Municipal Council. There was little else Settlement authorities could do, since by the time some 300,000 Japanese troops completely surround the foreign enclave, and the threat of an invasion was very real.

Japan engaged in diplomatic temper tantrums for the next week, refusing to attend the Nine-Power Conference and claiming that quantities of fresh food were found in the Sihang Warehouse after the siege. This, they said, was proof that Telfer-Smollett and the British were secretly aiding the Chinese. The British brushed off the allegations, but Japan’s relations with Britain and the United States continued to sour. A Chinese collaborationist government was established at Shanghai, and in April 1941, Xie was assassinated by four of his own soldiers acting as agents of the new government. After the war, an elementary school was renamed in his honor.

Hi Eric,

Really detailed information about the battle of Sihang warehouse. Thank you!

And I’m quite interested in the second last paragraph where says ‘The British pillbox gave the Chinese covering fire…… A Japanese machine gun was put out of action by British bullets’, could you tell me what’s the source of this? Thanks!

Regards

Nice article.

One small observation: the 4th photo “the “Chinese Alamo,” during the battle.” It cant have been during the battle as the Japanese flag is flying atop the building.