By Christopher Miskimon

The 1930s was a decade full of World War II’s antecedents. Fighting broke out at various points around the globe during this decade, and many consider the period to be a training ground for 1939-1945. In particular, fighting broke out between several nations in Asia; among these the fighting between Japan and China was no doubt the largest. It was a bloody and vicious series of conflicts that essentially bled into World War II. China had mass going for it. The Chinese could raise large armies, but training, equipment and unity were lacking. The country also needed foreign advisors to have any hope of well-organized and planned operations. The Japanese were, with exceptions, better trained and uniformly equipped. Being a more homogeneous nation they were better able to field disciplined formations and generally acted with professionalism in their planning. However, they could not hope to match the Chinese in numbers.

Largely ignored in the West, Japan and China fought a horrible large-scale battle for the city of Shanghai from July to November 1937. Though it happened at times, urban combat was not the norm during this period; Shanghai proved a terrible exception and provided a taste of things to come for anyone who was paying attention. Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze (Peter Harmsen, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2013, 310 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover) relates the story of this awful months long battle and its effect on later events.

Largely ignored in the West, Japan and China fought a horrible large-scale battle for the city of Shanghai from July to November 1937. Though it happened at times, urban combat was not the norm during this period; Shanghai proved a terrible exception and provided a taste of things to come for anyone who was paying attention. Shanghai 1937: Stalingrad on the Yangtze (Peter Harmsen, Casemate Publishing, Havertown, PA, 2013, 310 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover) relates the story of this awful months long battle and its effect on later events.

The battle began with small skirmishes and riots between various Chinese elements and local Japanese in Shanghai, some civilian, some military, mostly Japanese marines based near the International Settlement. Longstanding enmity meant the situation would eventually boil into open fighting, and now it did. The Japanese occupied a fortified position and had to keep the road to the nearby consulate and Japanese portion of the Settlement open. The Chinese sent in several of their best trained divisions to push their hated foes out of the city before enemy reinforcement could pour in.

Unfortunately for them, most Chinese formations were not yet fully trained and their attacks, though fierce, were poorly coordinated between their infantry, artillery, and what little armor there was. The battle began before Chiang Kai-shek’s troops were fully prepared. The Japanese, though outnumbered, were well coordinated, and Imperial Navy ships on the Yangtze River did terrible damage with their guns. Overhead, each nation’s air force vied for supremacy, but over time superior Japanese experience paid off.

Hastily dispatched Japanese reinforcements landed around the city hoping to cut off the Chinese troops, focused as they were on eliminating the pockets in Shanghai. This encirclement surprised the Chinese, sweeping aside the few untrained troops guarding the Chinese flanks. In response the defenders committed more troops. So did the Japanese, many of them hastily summoned reservists. Fighting was fierce; the Japanese were now learning to regard the Chinese soldier with respect, something they had not done before. While Japanese leaders were still confident of victory, they were alarmed at the high casualties their divisions were taking.

Despite the growing capability of the common Chinese soldier, leadership problems remained. Many Chinese officers held their rank through patronage. The numerous German advisors generally made little headway trying to train them; prejudicial Chinese attitudes and unwillingness to admit their ignorance doomed most German efforts. The few competent officers were ground away in months of attritional combat, which at times resembled the Western Front of World War I. A Chinese unit even became a “lost battalion.”

The Japanese had problems, too. Overconfidence led to several local defeats when Chinese troops stood and fought or ambushed their foes. Logistics troubles plagued them, and at one point some battalions were down to only 200 to 300 rifles and no machine guns. International opinion tended against them as well. Despite these issues, victory seemed inevitable, and by November the Chinese realized they could note hold the city. A gradual withdrawal from the front lines was accompanied in places by a scorched earth policy. By the second week of November 1937, it was over, and the Japanese occupied Shanghai, exacting terrible abuse upon the local civilians.

This book is meticulously researched, and vignettes are included from generals and privates alike. Civilian accounts, the bulk of them from residents of the International Settlement, abound. Most of the sources are translated Chinese works. The author weaves them together in a way that gives a sense of the battle’s breadth and horror. Readers interested in the history of the Sino-Japanese fighting of the 1930s will find this book a valuable addition to their libraries.

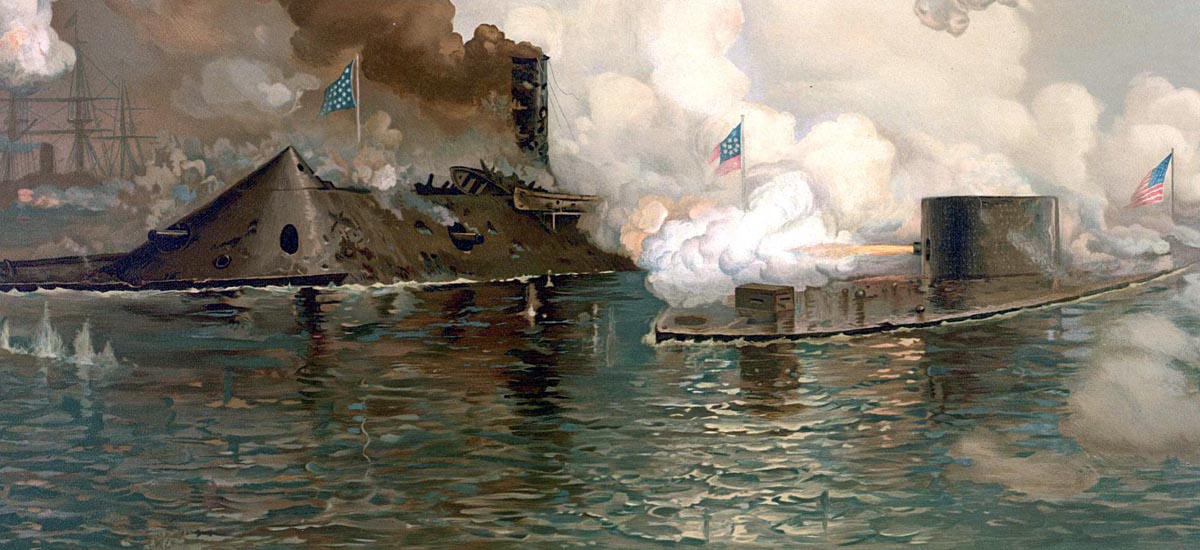

Surgeon in Blue: Jonathan Letterman, the Civil War Doctor Who Pioneered Battlefield Care (Scott McGaugh, Arcade Publishing, New York, 2013, 368 pp., photos, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover).

Surgeon in Blue: Jonathan Letterman, the Civil War Doctor Who Pioneered Battlefield Care (Scott McGaugh, Arcade Publishing, New York, 2013, 368 pp., photos, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover).

The idea of medical care during the American Civil War generally conjures horrifying images of limbs mangled by bullets, amputations, and the terrifying results of infection. Medical care had been that way for literally centuries. There was little care available and often soldiers would lie on the field where they fell for hours, even days. This book is the biography of a man who strived to change that condition and took military medicine on its first steps toward the modern era.

Before the conflict, Jonathan Letterman was an army surgeon whose postings included remote stations in Florida, Minnesota, New Mexico, and California. Like many of the combat officers of the war, Letterman spent time among the native tribes slowly and sadly being brought to heel by the army. After the War Between the States began, he was posted to the Army of West Virginia. About six months later he was promoted to the position of medical director of the Army of the Potomac.

In truth, Letterman was not qualified by experience for the job. Nevertheless, he had the trust of the Army’s leaders, and he did not betray it. Finding the army in bad condition after three months of fighting and defeat, the doctor leaped into action. New orders were issued on everything from the prevention of scurvy to the disposal of waste. Letterman reorganized field hospitals to make them more effective. He also created an ambulance service to speed casualties to treatment. Along the way he was present at four of the largest battles of the Civil War: Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg.

This book is a detailed look at military medicine and the workings of the U.S. Army during the American Civil War. The author deftly mixes the story of Letterman with the larger events occurring around him as he practiced his trade. No story of the Army of the Potomac is complete without examining the political machinations and decisions of its leaders, and the book explains these clearly. It is a fascinating read for anyone interested in the American Civil War or battlefield medicine.

Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: The Vietnam War Revisited (Edited by Andrew Wiest, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2013, 307 pp., maps, notes, bibliography, index, $13.95, softcover)

Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: The Vietnam War Revisited (Edited by Andrew Wiest, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2013, 307 pp., maps, notes, bibliography, index, $13.95, softcover)

The Vietnam War is an event America is still trying to understand. This focus is becoming perhaps more acute as the veterans of the conflict are now aging and old enough to have children wanting to understand their parents’ experience. This is a series of monographs, each its own chapter, examining some facet of the war.

A combination of academic authors and actual participants are used to examine diverse topics, many of which will be familiar to a student of the conflict. The strength of this work is in the new ways it examines these subjects. The book moves between grand overviews from higher level leaders and ground level views of the war by soldiers and civilians.

For example, one chapter is a broad telling of the 1946-1954 war between the Viet Minh and France. Aside from covering the actual events of the war, the author reviews the military forces of each combatant, troop strengths, and political effects of the conflict back in Metropolitan France. It gives the reader insight into what came later. Another chapter focuses on the civilians caught in the middle of the war. The plight of noncombatants in Vietnam is often touched on in other works, but this book goes more in depth, talking about how civilians lived and tried to stay out of the war’s way. Also covered is how the Vietnamese government’s programs and efforts affected them.

Overall, this book is well done and lacks only a few photos to round it out, although it does have a number of good maps to accompany the text. For someone interested in studying the Vietnam War this work will introduce a number of areas ripe for further study and reading.

Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, The Cold War and the Twilight of Empire (Calder Walton, Overlook Press, New York, 2013, 448 pp., photographs, maps, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover).

Empire of Secrets: British Intelligence, The Cold War and the Twilight of Empire (Calder Walton, Overlook Press, New York, 2013, 448 pp., photographs, maps, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover).

Great Britain is known for the strength, professionalism, and to some the ruthlessness of its intelligence services. The current arms of this branch can trace a lineage going back for centuries through the days of the British Empire. Indeed, to this day, the United Kingdom uses sources and networks initiated during those times and enduring. Even enemies of Britain respect the abilities of the various intelligence and counterintelligence organizations, such as MI5 that Britain can bring to bear.

Even when the empire was being dismantled, amid the new threats of the Cold War, British intelligence was hard at work around the globe, helping manage the process of decolonization and reacting to crisis situations as they arose. The empire was fading into history but the United Kingdom was still a power to be reckoned with. This book is a summary of just what MI5 did during the turbulent last decades of the 20th century.

For example, British intelligence operations during World War II are widely known, from the Special Air Service in North Africa to the codebreakers at Bletchley Park. However, often forgotten is how these groups continued after the war. Bletchley Park did not just shut down; it went right on collecting signal intelligence and breaking codes under a new name, Government Communications Headquarters. Some of the codes it broke related to former colonies and nations of the commonwealth.

As each former colony went its own way, MI5 was there, working against threats to British goals. Often the bonds it formed with the new intelligence agencies of these young nations were so strong the relationship simply continued after independence, working together on issues of mutual interest. Well written and extremely detailed, this book tells the tales of unknown events of the Cold War heretofore unknown outside classic spy novels.

Gettysburg: The Story of the Battle with Maps (The Editors of Stackpole Books, Stackpole, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2013, 151 pp., maps, bibliography, $19.95, softcover)

Gettysburg: The Story of the Battle with Maps (The Editors of Stackpole Books, Stackpole, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2013, 151 pp., maps, bibliography, $19.95, softcover)

The Battle of Gettysburg is still studied intensely despite the multitude of books, films and documentaries done on it over the years. One problem with the battle is its size. For some, it is just too big to comprehend. The exhaustive detail in which Gettysburg has been studied really only adds to this phenomena. There were simply so many moving parts to the engagement it can be hard to form a coherent linear picture.

This new book seeks to help clarify America’s pivotal battle of the Civil War. It is a step-by-step guide to the battle essentially using a map of the field to display the movements and fighting of the two armies in an almost hour by hour fashion.

The text uses present tense to describe the actions of each side as they maneuver to the battlefield, fight the first skirmishes, and are then drawn into the decisive battle that went on for two more days until the final Confederate defeat on July 3, 1863. The maps are easy to follow, and the units are detailed down to regimental level using simple symbols. This book is a good companion to the standard texts on Gettysburg, allowing the reader to easily use the book to follow the battle in a straightforward chronological fashion.

Viking: The Norse Warrior’s Unofficial Manual (John Haywood, Thames and Hudson, New York, 2013, 208 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $19.95, hardcover).

Viking: The Norse Warrior’s Unofficial Manual (John Haywood, Thames and Hudson, New York, 2013, 208 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, index, $19.95, hardcover).

The Vikings were a major threat to Europe for centuries. The approach of their raiding parties struck fear into the hearts of western Europeans as they were struggling to climb out of the Dark Ages. Unfortunately for students of the period, the Vikings often get sold short, being portrayed as nothing more than barbaric savages bent on simple plunder, a nation of outlaws. There is more depth to these Northmen, however; they had a thriving culture, a working society, and good reasons to act as they did.

Anyone interested in the Vikings and possessing a sense of humor should read this book. It is written as a training manual and introductory guide for the young Viking warrior. While a bit of a tongue in cheek approach, the work’s information is factual and well researched from historical documents. It goes into great detail about many aspects of the Vikings’ world and gives insight into their culture and worldview.

Reading almost as a how-to book, there are chapters such as “Weapons and Tactics,” “Going to Sea,” and “Life on Campaign.” Each is full of suggestions for how to attain victory, plunder, and glory. Truly, isn’t that all any true Viking wants from life? This is an easy to read and enjoyable book.

Stukas Over Spain: Dive Bomber Aircraft and Units of the Legion Condor (Rafael A. Permuy and Lucas Molina, Schiffer Publishing, Atglen, PA, 2013, 128 pp., photographs, bibliography, $34.99, hardcover)

The Junkers Ju-87 Stuka is one of the ubiquitous German aircraft of World War II. Its distinctive gull wings and the howling sirens often used during a dive bombing run set it apart from other aircraft, despite its obsolescence as that conflict went on. The Stuka saw other service than in the skies over Poland, France, and Russia, however. The aircraft’s baptism of fire came during an earlier conflict as part of a German proxy force during the Spanish Civil War.

This is a detailed examination of the Stuka’s first wartime service. The Condor Legion was a unit of German volunteers which went to Spain to fight on the Fascist side of the war. It was a combined land and air force. The air component is arguably the more famous due to its “terror” bombing campaigns over Spanish towns such as Guernica.

The word Stuka is an abbreviation for the German term for a dive bombing aircraft. While the name has stuck with the Ju-87, in reality it was not the only dive bomber there and any such plane could be called a Stuka, such as the HS-123 biplane, believed to be the only Stuka aircraft in Spain when Guernica was bombed. The actual Ju-87 arrived later but then became a widely used plane once in theater.

This work is representative of Schiffer Publishing’s aviation titles. It is a tightly focused topic but is obviously written by authors who have a deep interest for it. It is exhaustively detailed, well illustrated, and uses high-quality paper and binding with professional layouts of charts, photographs and well-done illustrations of the aircraft. For readers fascinated with the history of either the Luftwaffe or the Spanish Civil War, this book will prove of interest.

Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder (David Cressy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2013, 237 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Saltpeter: The Mother of Gunpowder (David Cressy, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2013, 237 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover)

Logistics are an often overlooked aspect of a nation’s ability to make war. During the 16th century and afterward, the technological marvel a European nation needed was gunpowder in ever increasing quantity. This book explains the storied history of how the British crown acquired this vital ingredient.

Early gunpowder varied widely in quality and did not keep forever in stockpiles, requiring the government to constantly search for new sources of saltpeter, which was often found in cellars and dung-saturated areas such as barns. The monarchy granted agents, known as saltpetermen, the right to enter private property and dig for it. Landowners were required to allow them access and assist with transport.

Naturally, this did not sit well with landowners who complained, petitioned and resorted to outright bribery to keep the saltpetermen at bay. It was such a necessity the government had little choice but to continue the practice until new sources became available in later centuries.

Short Bursts

Soviet Naval Aviation 1946-1991 (Yefim Gordon and Dmitriy Komissarov, Hikoki Publications, 2013, 368 pp., photographs, $56.95, hardcover). The largely unknown Soviet Naval Aviation service began in World War II flying fighters and torpedo bombers and grew into a large force of fighters, bombers, and reconnaissance planes during the Cold War. It posed a major threat to NATO shipping and naval forces.

Soviet Naval Aviation 1946-1991 (Yefim Gordon and Dmitriy Komissarov, Hikoki Publications, 2013, 368 pp., photographs, $56.95, hardcover). The largely unknown Soviet Naval Aviation service began in World War II flying fighters and torpedo bombers and grew into a large force of fighters, bombers, and reconnaissance planes during the Cold War. It posed a major threat to NATO shipping and naval forces.

Russian Security and Paramilitary Forces since 1991 (Mark Galeotti, Osprey, 2013, 58 pp., $18.95, softcover). While the Russian Army has shrunk, its internal security forces have proliferated and been involved in numerous conflicts. Meanwhile, sanctioned private armies have flourished as well. Part of Osprey’s Elite Series.

Dingo Firestorm: The Greatest Battle of the Rhodesian Bush War (Ian Pringle, Helion and Company, 2013, 304 pp., $49.95, hardcover). Operation Dingo in 1977 was the largest battle of the Rhodesian Bush War, a cross-border attack by Rhodesia upon the Zimbabwe African National Liberation Army. The political background is described along with the battle itself.

Manzikert 1071: The Breaking of Byzantium (David Nicolle, Osprey, 2013, 96 pp., $21.95, softcover). This defeat of the Byzantine Empire finally broke its power and began a chain of events which eventually led to its downfall. The battle is also seen as a primary cause of the subsequent Crusades.

A Disease in the Public Mind: A New Understanding of Why We Fought the Civil War (Thomas Fleming, Da Capo, 2013, 354 pp,, $26.99, hardcover). A reassessment of the role of slavery as a cause and purpose of the Civil War. Relates the importance of the issue, which has been downplayed by some in recent years.

A Disease in the Public Mind: A New Understanding of Why We Fought the Civil War (Thomas Fleming, Da Capo, 2013, 354 pp,, $26.99, hardcover). A reassessment of the role of slavery as a cause and purpose of the Civil War. Relates the importance of the issue, which has been downplayed by some in recent years.

The Real History of the Vietnam War: A New Look at the Past (Alan Axelrod, Sterling, 2013, 372 pp., $24.95, hardcover). The fifth in a series by the author covering American wars. The book details the events of the war and analyzes its consequences and long term impact.

Allegany to Appomattox: The Life and Letters of Private William Matlock of the 188th New York Volunteers (Valgene Dunham, Syracuse University Press, 2013, 253 pp., $29.95, hardcover) This soldier’s letters, found in an attic, are recounted here. Background information is included, telling where the soldier was when each letter was written and what historical events were occurring.

East of the Oder: A German Childhood under the Nazis and Soviets (Luise Urban, Spellmount, 2013, 239 pp., $29.95, hardcover) A memoir of a young girl displaced from her home after World War II. Faced with starvation, they flee west.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments