By Arnold Blumberg

On October 20, 1740, Charles VI, Holy Roman Emperor and ruler of Austria, died, leaving his vast holdings and titles to his 23-year-old daughter, Maria Theresa. The young, inexperienced archduchess inherited a troubled empire. Her father’s bequest left her holding sway over 11 million subjects and extensive European territory, including parts of the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, Hungary, and Italy. But Charles’s lack of a male heir made Maria Theresa’s assumption of power suspect in the eyes of many foreign courts. The unsettled situation invited the unfriendly attention of any neighbors who had the means and ambition to take advantage of Austria’s dire condition. Unfortunately for the Hapsburgs, such a troublemaker resided immediately to their north.

Frederick II had come to the throne of Prussia a mere three months before Maria Theresa inherited the Austrian crown. At 28, Frederick was intelligent, ambitious, self-confident, and cynical. He wanted to expand the territorial limits of his country; he felt he had no choice. Prussia sat squarely in the middle of Germany, one of a number of loosely organized independent states. With a population of less than two million, Prussia was surrounded by often hostile countries—France to the west, Austria to the south, and Russia (which controlled Poland) to the east. To survive, Prussia had to expand, and the path of expansion pointed directly toward Austria.

An Opportunistic Frederick II

By the fourth decade of the 18th century, the Hapsburg government in Vienna had been gravely weakened by the ongoing strain of international conflict: first the five-year Polish War of Succession (1733-1738), then the military drubbing it had received fighting the Ottoman Turks between 1737 and 1739. The result of almost a decade of strife was a bankrupt administration that now could muster a demoralized army of less than 100,000 men. There was unrest in many parts of the empire, and no foreign allies offered to help with the strain. Even worse, claims by the Elector of Bavaria, Charles Albert, to the Austrian lands and the title of Holy Roman Emperor had created a succession crisis that pitted members of Maria Theresa’s realm against each other. Austria’s predicament made her look like easy prey for anyone strong enough to move against her.

Frederick of Prussia, with the instincts of a predator, decided to take advantage of the chaos plaguing Vienna. Possessing a large war chest of over 10 million thalers and a standing army of 83,000 well-trained (if untested) soldiers, the king felt confident that a swift land grab from Austria would not be much of a problem. He decided to annex one of the wealthiest provinces owned by the Hapsburgs—Silesia. Encompassing 14,000 square miles of territory contiguous to Prussia’s eastern border, Silesia had a population of 1.2 million. It was rich in agriculture, iron, and coal, and such cities as Breslau and Neisse were thriving trade centers. The revenues derived from Silesia alone provided Austria with 21 percent of the funds from her German hereditary lands and 10 percent of the money available from all the Hapsburg dominions. Moreover, the quality of the region’s military recruits—an asset Frederick dearly coveted—was quite high.

On December 14, 1740, Frederick left Berlin and traveled the 60 miles to Crossen to join an invasion force being assembled there by Field Marshal Count Kurt Christopher von Schwerin. Upon his arrival, the king joined an army comprising 20,000 infantry and 8,000 cavalry. An artillery train of 34 bronze cannons had also been assembled. A reserve element of 12,000 additional men followed Frederick’s departure from Berlin. Two days later, the army crossed the Silesian border and that night camped near Schweidnitz. Frederick wrote to his minister for foreign affairs, Heinrich von Podewils: “I have crossed the Rubicon with flags flying and drums beating and I have reason to anticipate all possible good from this enterprise.”

For the advance into Silesia, the king divided his army into two parts. One, overseen by the monarch, marched along the Oder River toward the garrison town of Glogau; the second, under Schwerin, moved a few miles to the south toward Liegnitz. The columns traveled in lines 25 miles long, at a rate of 15 to 20 miles a day. At the head of each corps rode a group of dragoons scouting for the enemy and the best routes of march. About 1,000 yards behind, an advance guard of infantry followed the horsemen. Snaking their way along rough paths and through woods, the infantry regiments formed long ranks interspersed with their baggage wagons. The artillery moved between the infantry units, creaking along at a snail’s pace and causing bottlenecks at every water crossing or forest path. To either side rode contingents of heavy cavalry. Bringing up the rear were groups of cavalry and infantry whose prime purpose was to gather up stragglers and deserters.

After less than a week on the march, the Prussians had covered more than 60 miles. They prepared to blockade Glogau, while Schwerin closed in on Liegnitz. Frederick sent orders to Prince Leopold II Maximilian to bring the reserve force to Glogau. The invasion was shaping up nicely.

The Austrian Response: Browne’s Stalling Actions

As the Prussian juggernaut swept into Silesia, the Austrian government struggled to meet the crisis. Completely surprised by the invasion, Maria Theresa’s counselors were divided as to the proper response. Many wanted simply to cede Silesia to Frederick and make the best peace possible. A small faction at court led by the secretary of the Secret Council, Johann Bartenstein, reinforced the empress’s inclination to resist the aggressor at any cost. To that end, instructions were sent to the Austrian commander in Silesia to defend the place as best he could. It was a daunting task.

Lieutenant General Count Maximilian Ulysses von Browne was a 35-year-old Irish Jacobite immigrant and a skilled veteran of the Turkish and Italian campaigns of the 1730s. Assigned the Silesian post in December 1740, Browne’s command consisted of 6,000 men, mostly garrison troops tethered to the fortress towns of Glogau, Brieg, Neisse, and Glatz. He was told that only a few hundred more infantry and cavalry troops would be sent to him. Outnumbered 4-to-1, Browne ordered the fortified cities of Glogau and Brieg to delay the enemy as long as possible while he retired with a 2,500-man mobile force behind the Neisse River to await what few reinforcements he could get.

As the Hapsburgs frantically reacted to the Prussian attack, Frederick moved with his main force, commanded by Schwerin, to Breslau, the capital of Silesia. The move was exceedingly slow due to the snow and mud that covered the landscape. At the same time, Glogau was put under siege by Prince Leopold. Meanwhile, Frederick learned that an Austrian army was forming to come to Browne’s aid. Surprised at the alacrity of his opponent’s response, Frederick ordered Schwerin to take 6,000 men and form a barrier to the west to prevent enemy forces from entering Silesia from Bohemia and Moravia. Continuing his move on Breslau, the Prussian emperor accepted the surrender of the city’s 40,000 people on January 1, 1741.

Frederick next turned his eyes southwestward toward the fortress towns of Neisse and Glatz, whose capture would put all of Silesia under his control. On January 6 he sent word to Schwerin to take the two cities as soon as possible. As his couriers raced to spur on Schwerin, news reached the king that attempts to take the garrisoned towns of Glogau, Brieg, and Glatz were failing; all were standing firm against their Prussian besiegers. With the winter weather growing worse, Frederick’s hope of gaining uncontested control over Silesia before the Austrians could put sufficient forces in the field was fading. The longer it took to digest Silesia, the more chance the Hapsburgs might find outside allies to help thwart the Prussian king’s aggressive designs.

driven back by massed artillery.

By mid-January, Frederick was determined to take the fortress town of Neisse. To do so would secure the southern part of Silesia and cause the collapse of resistance at other strongpoints still holding out against Prussian attack. Frederick planned to bombard Neisse into submission. A formal siege was out of the question—the increasingly harsh weather would make it too difficult to keep his army adequately supplied. Taking the place by storm was not an option, either, since it was too well garrisoned and its defense, led by Colonel Baron Wilhelm Morwitz von Roth, was proving to be formidable.

While Frederick ringed the town with heavy artillery, Schwerin was tasked with destroying Browne, who was operating south of Neisse. Outnumbered, Browne slowly pulled back in front of the Prussians, skillfully avoiding pitched battle. He used parties of ruthless mounted irregulars, Croats and Hungarian hussars, to impede the Prussian advance and interrupt their lengthening supply lines. By late January 1741, due to extremely cold weather and heavy snowfall, Browne had stymied Schwerin’s efforts and was safely encamped in southern Silesia, on the Moravian border. The campaign was all but over, with the Prussians controlling most of Silesia except for the fortified towns of Glatz , Brieg, Glogau, and Neisse. Schwerin placed his men in a 200-mile cordon from Liegnitz to the Hungarian border while the rest of the army went into winter quarters throughout Silesia.

Count Neipperg Leads the New Austrian Army

Back in Berlin, Frederick engaged in intensive diplomacy to create a coalition including Prussia, France, Saxony, and Bavaria that would effectively dismember Austria. At the same time, the British and Russian governments were attempting to form their own alliance with Austria, Saxony, and Holland to conquer and partition Prussia. Frederick was not aware of this threatening development, but he sensed that his position would not be secure until he subdued the stubborn Silesian fortresses. Determined to do so, he returned to the seat of the war in the second half of February 1741.

If Frederick was hoping for peace after he had digested Silesia, the Austrian empress was equally set on destroying her opponent. Her prospects improved noticeably when Great Britain advanced Austria a huge war loan to pay for more troops, both regulars and irregulars. The new troops were central to a plan that had been formulated in December. An Austrian army was to be marshaled at Olmutz, Moravia, behind a covering screen provided by Browne’s command. The Austrians intended to eject Frederick from Silesia with this surprise new force .

The leadership of the new Silesian army should have gone to Browne, but the ultraconservatives of the Austrian Supreme War Council, along with Maria Theresa’s consort, Grand Duke Francis, opted for a native-born general. Their choice fell on Field Marshal Count Wilhelm Reinhard von Neipperg. The count was the son of an Imperial field marshal and a member of an aristocratic family from Swabia (south Germany). He had entered Austrian service in the first decade of the 18th century, rising to major general by 1717, and participated in the war against the Ottoman Empire. With the conclusion of hostilities, he became a mentor and tutor to Prince Francis. In 1723, Neipperg was promoted to lieutenant general and saw action in a new Turkish-Austrian war that was fought between 1737 and 1739. Conspicuous for his part in safeguarding the Austrian retreat after the defeat at the Battle of Kiotika, Neipperg was authorized to conclude peace terms with the Ottomans. The result was the Treaty of Belgrade, which ceded to Turkey northern Serbia, northern Bosnia, and parts of Wallachia, thus forfeiting all the territorial gains achieved by the Treaty of Passarowitz 21 years earlier. Displeased by the terms, Charles VI had Neipperg placed under house arrest in Vienna.

The Silesian crisis, along with the influence of his former pupil Francis, brought the general back to field command in late 1740. Personally brave, competent but cautious, Neipperg was far from sanguine about the upcoming campaign to retake Silesia. He doubted that the government had enough troops to make the enterprise a success. His infantry force was understrength and poorly trained; his cavalry was seasoned but also understaffed; and supplies for the entire army were inadequate. As a result, Neipperg did not start his campaign until late March 1741. With an advance guard of German cavalry, Hungarian hussars, and other irregular horsemen, followed by the main army of 12 infantry battalions (10,000 foot soldiers), 11 cavalry regiments (about 6,000 troopers), 16 cannons, and a pontoon train, Neipperg moved into Silesia. He headed for the area due south of Neisse, hoping to drive a wedge between Frederick’s main body and Schwerin’s outpost line, destroying both in detail.

Frederick’s Camp at Mollwitz

If Neipperg was laboring under difficult conditions, he could take comfort in the knowledge that his enemy was suffering as well. All through the winter, Browne had waged an aggressive guerrilla war against Schwerin’s forces. Prussian patrols and convoys were ambushed, supply lines interdicted, and a sense of insecurity pervaded the entire Prussian army in Silesia. Audacious attempts to capture both Schwerin and King Frederick barely failed.

As the Austrian liberation army marched into Silesia, Frederick established his headquarters near the small village of Mollwitz, near the town of Brieg. His overall military situation was strained due to the dispersal of his units. The main Prussian army was spread out north and west of Neisse. Schwerin’s forces were south and east of the city, while other detachments were still struggling to reduce various Austrian strongpoints. In early April the Prussian king finally learned of the existence of Neipperg’s army. He wanted to pull all his forces together, but Schwerin insisted on keeping his men placed around the Bohemian and Moravian border in the mistaken belief that this would prevent enemy forces from entering Silesia. He persuaded the king that the recent snowfall and lack of forage would delay any Austrian efforts to cross the mountains into Silesia for several weeks.

Completely inexperienced in the art of war, Frederick felt that he had no choice but to listen to his second-in-command. The 56-year-old Schwerin was one of the most respected officers in the Prussian Army. Born in Pomerania, he had participated in the Battles of Blenheim, Ramillies, and Malplaquet during the War of the Spanish Succession. Schwerin was promoted to lieutenant general in 1739, and the next year he was named count and field marshal by Frederick for his outstanding military and diplomatic achievements. Until the king mastered military command, he would rely on Schwerin’s manifest ability and self-assurance.

While Schwerin convinced the king that the Prussians had nothing to worry about from the Austrians, Neipperg was proving him wrong by moving his army, albeit slowly, over snow- and mud-covered roads south of Neisse. The Austrian field marshal intended to take Breslau, cutting between Frederick’s and Schwerin’s commands and severing the Oder River supply line—the main artery of the Prussian forces in Silesia.

When Frederick realized the approaching danger, he immediately ordered a concentration of forces north of the Neisse River. To effect this concentration, the Prussians marched 18 miles a day, while the Austrians managed only five miles a day. The torpid pace of the Hapsburg force enabled Frederick to escape immediate destruction. By April 8, he had gathered his separate commands and headed north to the supply center at Ohlau. There he intended to block any enemy advance to Breslau. That same day, Frederick learned that the Austrians, marching on the west side of the Neisse River, had gotten between him and Ohlau. The king decided to wheel to the right, take position in villages four miles to the south of the hamlet of Mollwitz, and prepare his 21,000 men to fight the Austrians coming down from the north.

The Austrians and Prussians Prepare For Battle

As the Prussians girded themselves for the inevitable battle, Neipperg was closing in on his enemy. He did not know it. Unaware of Frederick’s exact position and assuming that his opponent had only about 8,000 men, Neipperg kept moving toward Ohlau. He spent April 9, a day of heavy snowfall and frigid temperatures, resting and gathering much-needed supplies. The Austrian cavalry scouted the Mollwitz area but failed to detect the Prussian presence. Neipperg sensed that he was in the midst of his opponents’ scattered forces, but he was unsure how to proceed. Still thinking that he vastly outnumbered his adversary, Neipperg was more alarmed about his supply situation. He intended to continue on to Ohlau the next day to secure much-needed foodstuffs.

April 10 found the Prussian army moving north in five columns over ground covered by two feet of frozen snow. Reports of small cavalry clashes between the Prussian advance guard and Austrian pickets reached Neipperg, who although surprised, calmly and quickly ordered his troops to form to meet the oncoming enemy. His task was complicated by the fact that his men were facing in the wrong direction, looking to the northwest of Mollwitz instead of the southeast. To face the enemy, the entire Austrian army had to execute a 180-degree turn. Despite the urgency of the situation, Neipperg told his staff that he expected nothing less than complete victory.

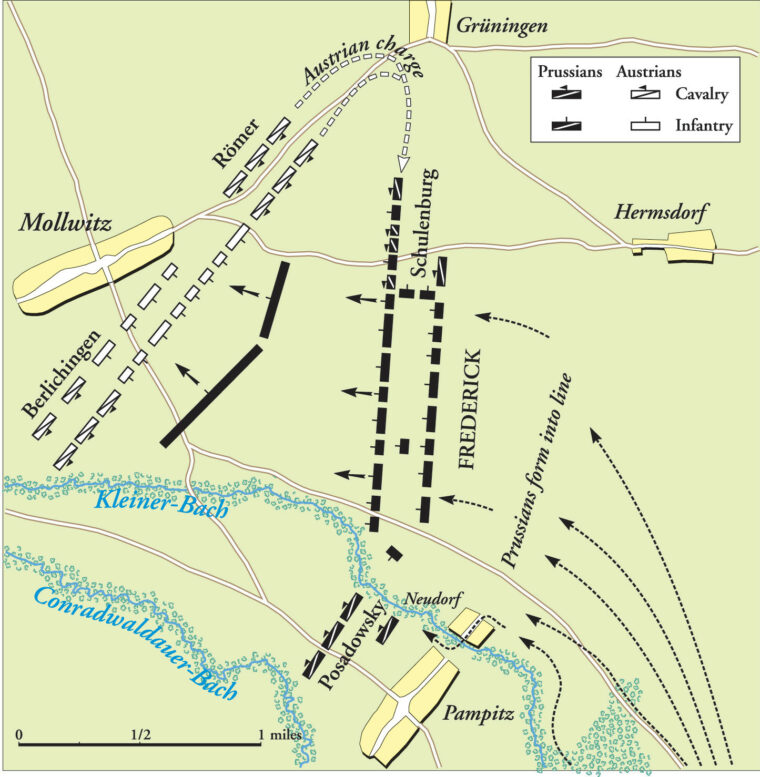

Less than 1,000 yards from his prey, the Prussian king ordered his army into battle formation. Its five columns swung to the right in two parallel lines; the first line fell under the command of Schwerin, the second under Prince Leopold. Cavalry under Count Adolf Friedrich von der Schulenberg took up positions on the right, while more squadrons were placed on the left under Colonel von Posadowsky. The Prussian artillery was placed along the entire front.

Meanwhile, the Austrians, seeing their enemy on their doorstep, had to deploy a force that not only was facing the wrong way, but for the most part still nestled in their camps. Mustering six regiments of cavalry, Lt. Gen. Carl Romer screened the infantry of General von Goldy as they frantically formed a widely spread-out battle line. Romer moved his horsemen to the Austrian left, while General Baron Johann Friedrich Berlichingen’s cavalry stood on the Austrian right. Friendly artillery slowly arrived and was filtered into the line at various points.

On the surface, the opposing forces appeared to be evenly matched. The Austrians had 19,000 men in 16 infantry battalions, 14 grenadier companies, and 8,000 troopers in two hussar, six heavy cavalry, and five dragoon regiments, along with 19 cannons. The Prussians fielded 21,600 men in 31 infantry battalions, 33 cavalry squadrons, and 53 guns.

As the Prussians neared Mollwitz, they realized to their horror that there was not enough room to deploy the entire first line as envisioned in the plan of attack. The lack of space squeezed out seven infantry battalions and all of the left-wing cavalry, considerably reducing Prussian striking power on that flank. As a result, the orphaned infantry units were reduced to acting as a right-flank guard for Prince Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau’s second line. The displaced cavalry had to be moved behind and to the left of the second line. There it was formed in column and poorly placed to take part in the upcoming fight. The repositioning of the units took precious time—90 minutes in all. When it was finally ready, the Prussian formation occupied a level plain 3,000 yards long. Its left flank was protected by a small stream with swampy banks, its right by a tiny wood. The space between the two friendly lines was about 150 yards deep. The Prussian delay materially aided the Austrians in their efforts to form their own defense line.

The Battle of Mollwitz

At 1 pm, Frederick’s army started to move toward Mollwitz. Its artillery tried to keep pace and intermittently stopped to lob shells at the Austrian line, which was still in disarray, with few units firmly in place. As the Prussians advanced, clouds of horsemen could be seen coming from the Austrian left near Windmill Hill east of Mollwitz. The unexpected mounted avalanche comprised the 4,500 troopers of Romer’s four cuirassier and two dragoon regiments. Romer had been ordered not to attack until the Austrians had established their defensive line, but stung by Prussian artillery fire, he unleashed his command prematurely in a furious charge of revenge.

Romer’s onslaught caught Schulenberg’s troopers in the open as they belatedly wheeled to face their attackers. Sweeping forward in two lines, the 30 Hapsburg squadrons took their 10 enemy counterparts at almost a standstill, scattering them in all directions. But the Austrians suffered heavily from the Prussian infantry battalions positioned between the two Prussian lines, as well as from grenadier companies that had been interspersed with the Prussian right wing cavalry. Canister from the Prussian artillery on the flank also caused considerable casualties among the attacking horsemen.

Shocked at what he was witnessing, Frederick, who had come over to the army’s right, attempted to rally some of the broken Prussian cavalry. But all his attempts proved futile, and the king was carried away by his routed horsemen. Schulenberg was killed during the melee, as was Romer, who was laid low by a pistol shot. Exposed to enemy gunfire and flashing sabers, Frederick was persuaded by Schwerin to quit the field. The badly rattled king spent the remainder of the day wandering the nearby countryside, narrowly escaping capture by Austrian hussars at the village of Oppelin, certain that his first battle had ended in unmitigated disaster.

While the Prussian monarch fled for his life, the Battle of Mollwitz raged on. Schwerin’s practiced eye saw that the Austrian cavalry assault was beginning to lose momentum as it turned from the defeated Prussian cavalry to the intact Prussian infantry and artillery. On cue, Prussian infantry battalions with parade-ground precision turned to face the enemy horsemen, blasting them from both front and rear. Piecemeal, Austrian foot battalions joined the fray, but found themselves halted and forced to fall back by disciplined volleys of Prussian musketry.

After five hours of hard fighting, Schwerin, despite being wounded, was able to reorder the second line and calm his men by the example of his personal bravery and confident manner. Slowly, as the afternoon dragged into evening, the Austrian losses inhibited their ability to sustain their forward firing line or engage in determined cavalry attacks.

As the fight raged on the Prussian right, Berlichingen’s Austrian cavalry hammered the enemy left. Although some initial penetrations were made, the Austrians were bloodied by enemy musket fire and stalemated. Neipperg ordered the horsemen to reinforce Romer’s men. But the fatigued Austrian cavalry was a spent force by this time, and the infantry was hesitant to approach the storm of lead being poured into them by the unbroken Prussian infantry.

Sensing that the enemy was on its last legs, Schwerin ordered his infantry to make a general advance against the now-weakened Austrian right. Marching silently and in perfect order, stopping to shoot and then moving forward, the Prussian foot regiments, with some supporting artillery, steamrolled over the disorganized and demoralized Austrians on the right wing. Within an hour, that part of Neipperg’s front dissolved. Seeing the situation develop but being helpless to stop it, Neipperg called for a general retreat. Disordered but by no means routed, the Austrians quit the field. With no organized Prussian cavalry available, Schwerin did not attempt a battlefield pursuit.

Infantry “Like Caesar’s”

By the end of the fighting, more than 4,660 Austrian and 4,550 Prussians were killed, wounded, or missing. Frederick complained long and loudly about his cavalry’s poor performance, but he proclaimed that the infantry, “like Caesar’s,” had saved the day. The battle had two vital results that, in time, would alter European history. First, it opened up for Frederick the prize he most wanted—Silesia—although it would take the Second Silesian War and the Seven Years’ War to confirm the conquest of the province into the Prussian state that started at Mollwitz. Second, the battle showed that Prussia was militarily capable. Frederick learned a great deal from the confused struggle—he later claimed, “Mollwitz was my school.”

Building on the lessons he learned at the cost of his soldiers’ blood, Frederick immediately instituted a program of reform for his cavalry that bore fruit within two years at the Battle of Chotusitz, when they drove the Austrian army from the field. He also intensified infantry training and introduced an instruction program for senior officers. In doing so, the king instilled in his men a sense of tempered aggression that would prove to be the guiding philosophy of war for all future Prussian endeavors. The Battle of Mollwitz, although far from a total tactical victory, nevertheless engendered pride and confidence in the Prussian army and the budding nation still taking shape at the turbulent center of the European continent.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments