By Helen Hannon

The unique persona of Charles Russell Lowell, a gifted Union cavalry officer from Massachusetts, inspired a series of memorials in his honor, ranging from famous monuments to obscure frontier forts. Each in its way sought to perpetuate the memory of Lowell, a shining presence who was mortally wounded at the Battle of Cedar Creek, Virginia, in October 1864.

Lowell was born in Boston on January 2, 1835, educated at Boston Latin and Boston English Schools, and graduated first in his class at Harvard College in 1854. After graduation, his first job was in a merchant house, but an interest in metallurgy brought him to the Ames Iron Works in Chicopee, Massachusetts. He next took a position at the Cooper Hewitt rolling mills in Trenton, New Jersey.

Serious lung problems compelled Lowell to leave iron working, and he accepted a post in the office of Boston businessman John Murray Forbes. His health continued to fail, and in hopes of recovery Lowell went to Europe in 1856. His health improved, and he took the opportunity to learn several European languages and tour extensively. While in Morocco, he became an excellent horseman, with even such skilled riders as the Arabs praising his ability. He also took lessons in swordsmanship and observed the military systems of the French troops in Algiers and the Austrians in Italy.

Returning home in 1858, Lowell worked briefly as a tutor for the Forbes family, then became treasurer of the Burlington and Missouri Railroad in Dixon, Illinois. An opportunity to again work in metallurgy brought him to the Mount Savage Ironworks in Cumberland, Maryland, in November 1860. After Fort Sumter was fired upon in South Carolina and Massachusetts troops were attacked in Baltimore in April 1861, Lowell went to Washington to obtain a commission in the army. He entered the service as a captain in the 3rd Regiment, U.S. Cavalry, on May 14, 1861. Physically, Lowell was 5 feet, 8 inches tall, light and agile—the ideal body type for a cavalryman. He participated in Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s ill-starred Peninsula Campaign in 1862 and was brevetted a major for his services. He continued to serve as an aide to McClellan, distinguishing himself at the battles of Malvern Hill, South Mountain, and Antietam.

Lowell accepted a commission as colonel of the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry and returned to Boston to recruit the regiment. While in Boston, Lowell married Josephine Shaw on October 31, 1863. His new brother-in-law, Robert Gould Shaw, became colonel of the famed, colored 54th Massachusetts Regiment. An officer quoted in the Harvard Memorial Biographies, a collection of biographies of Harvard Union war dead, recalled, “I shall never forget the effect of his [Lowell’s] appearance. He seemed a part of his horse, and instinct with a perfect animal life. At the same time, his eyes glistened and his face literally shone with the spirit and intelligence of which he was the embodiment. He was the ideal of the preux chevalier.”

The main task of Lowell’s regiment in Virginia was to contain Confederate Colonel John Singleton Mosby and his cavalry. By July 1864, Confederate Maj. Gen. Jubal Early had been stopped in his offensive against Washington. On July 26, Lowell was put in charge of a provisional brigade that included the 2nd Massachusetts and men from various dismounted camps around Washington. Later, Maj. Gen. Phil Sheridan combined Lowell’s command with Brig. Gen. John Buford’s former brigade of regular cavalry and artillery, which he designated the Reserve Brigade. They were in action every day for weeks.

At the ensuing Battle of Cedar Creek, on October 19, 1864, Lowell was hit twice by enemy bullets. The first bullet did not break his skin, but collapsed his lung. He refused to leave the field because it had not drawn blood. He needed assistance, however, to get back on his horse and could only whisper his orders. When the regiment charged, he was hit again and paralyzed. Lowell had survived 13 horses shot out from under him, but his luck had run out. He lived until 9 am the next day, issuing final orders and sending messages to his family. The orders promoting him to brigadier general had been signed on the same day that he was mortally wounded.

Sheridan mourned Lowell’s loss. “I do not think there was a quality I could have added to Lowell,” he said. “He was the perfection of a man and a soldier. I could have been better spared.” Fellow cavalryman George Armstrong Custer said with equal conviction, “We all shed tears when we knew we had lost him. It is the greatest loss the Cavalry has suffered.” Those who knew him considered his death a national loss. Maj. Gen. William Dwight, seeing Lowell go by at Cedar Creek, would later write, “They moved past me, that splendid cavalry. Lowell got by me before I could speak, but I looked after him for a long distance. Exquisitely mounted, the picture of a soldier, erect, confident, defiant, he moved at the head of the finest body of cavalry that today scorns the earth it treads.”

The day of Lowell’s funeral started out with intense rain, but the sun went in and out that morning. The sun came out again as the cortege entered Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Mourners stood around the elevated mound of the grave, and the opening was concealed with evergreen boughs and flowers. The pallbearers lowered the coffin slowly and three volleys of musket fire were discharged.

The site was quite different from what it is today. Mount Auburn was relatively new in 1864, and there weren’t many burials. Today, Lowell’s grave is easily found on the family lot. His monument is a simple granite stone. Rounded at the top, it is 28 inches high, 15 inches across, and five inches wide. The only decoration is a set of crossed sabers over his name. Aside from basic family information, only the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry is listed on the stone. Although entitled to burial with the full honors of a brigadier general, the family used Lowell’s rank of colonel. As Dr. George Putnam stated during his oration at the funeral, it was the title “most familiar and endeared to his family and friends.”

A more distant memorial to Lowell was located in Tucson, Arizona. On July 29, 1866, C Troop, 1st Cavalry, arrived at Camp Tucson. William Dean, their captain, had been consistently ill and was not well enough to assume command duties. First Lt. Charles H. Veil, who had served on Lowell’s staff as provost marshal, renamed the post Camp Lowell. Veil wrote that Lowell “was a young and gallant officer and had he lived would have made a record second to none.” Keeping order in the rough-and-ready Tucson settlement was difficult, drunkenness being the most severe problem. In March 1873, Brigadier George Crook, another veteran of Cedar Creek and the battles in the Shenandoah Valley, ordered a new post built seven miles out of town. It retained the name Camp Lowell until it became Fort Lowell in 1879. The troops there provided escort duty and when necessary saw action in the Indian Wars. Among the people who served at the fort was Walter Reed, who later would become well-known for his work against yellow fever. Another was Achilles La Guardia, bandmaster of the 11th Infantry and the father of Fiorello LaGuardia, the future mayor of New York City. The facility was closed in 1891.

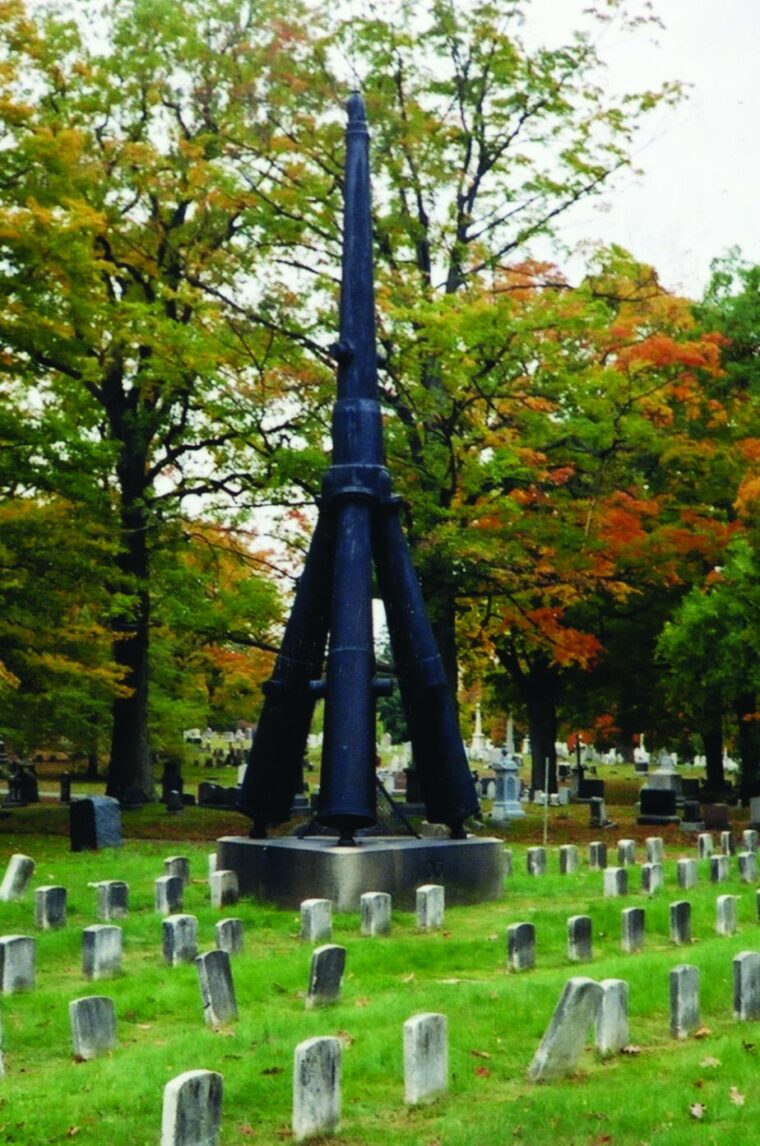

On October 29, 1873, Charles Russell Lowell Post No. 7 of the Grand Army of the Republic dedicated a cemetery lot and monument for the interment of all Civil War soldiers at Mount Hope Cemetery in Boston. On the lot the post placed a striking memorial consisting of four cannons. Mount Hope Cemetery, done in the elegant style of Mount Auburn Cemetery, was the first “garden” cemetery in the United States. It has elaborate memorials to veterans of the Civil War, Spanish-American War, and the two world wars. The monument was recently restored with funding from the George B. Henderson Foundation and the generosity of Albert H. Gordon and John Lowell.

In 1869, a memorial was proposed for “those sons of Cambridge who had perished in the war recently brought to a close.” The Cambridge Common was chosen, in part, because this was where George Washington first took command of the American Army during the Revolutionary War. The memorial is over 55 feet high and specifically placed so that it can be seen from every point in the cemetery. The official dedication took place on Wednesday, July 13, 1870. Throngs of people were in the street. Lowell’s name was the first name on the first tablet, prominently centered above the 470 Cambridge men who had laid down their lives in defense of their country.

James Russell Lowell, Lowell’s uncle, played an active role in the next memorial to his nephew. He wrote to Mrs. Sarah Shaw, the mother of Lowell’s widow, Josephine Shaw Lowell, and Colonel Robert Gould Shaw in September 1876, explaining that he had been asked for a photograph of his nephew “for [Martin] Milmore, the sculptor who wishes to put him among the figures on the Soldier’s Monument for Boston Common.” The Soldiers and Sailors Monument was dedicated on September 17, 1877, the 15th anniversary of the Battle of Antietam. There are four bronze reliefs on the monument. Lowell, Shaw, and 38 others are featured on the monument. The regiments are marching past the State House after receiving their flags from Governor John Andrew. The reliefs were made by the Ames Foundry in Chicopee, Massachusetts—the same foundry where Lowell worked when he was 19 years old.

Memorial Hall was the first large-scale fund-raising project by the Harvard alumni. In 1865, the Committee of Fifty was formed to spearhead the drive for subscriptions. Located just outside the famed Harvard Yard, Memorial Hall was intended to stand alone and serve as a conspicuous reminder of the Harvard men who had died fighting for the Union in the Civil War. Designed by Henry Van Brunt in Ruskin Gothic style, it is really three buildings: a memorial chamber, a banquet hall, and a theater. The transept is surrounded by marble plaques listing the names of the fallen. The plaques are in order of the school the students attended, their class year, dates of death and, if known, the battle where they they lost their lives. Harvard men who died fighting for the Confederacy are not represented. Lowell’s plaque is located on the Annenberg Hall side of the building.

Another tribute to Lowell in Memorial Hall is an Italian marble bust by sculptor Daniel Chester French, who is probably best known for the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. The bust was commissioned primarily on account of the efforts of Rev. Charles Humphreys, the chaplain in the 2nd Massachusetts Cavalry. In his autobiography, Humphreys wrote that French regarded the Lowell commission as a very important work and was anxious to do his best because he considered Lowell an inspiring subject. The sculptor later wrote that it “is one of the few things of mine upon which I can look without more regret than pleasure.” It was placed in Memorial Hall on March 8, 1886. The best proof Humphreys had of the sculptor’s success was the satisfaction of Lowell’s widow. Humphreys originally had difficulty getting her permission for the bust, but after visiting the sculptor, she wrote Humphreys, “It is wonderful that Mr. French should have been able to get so much character into the bust, and I am perfectly satisfied to have it remain as a likeness of Colonel Lowell.”

Dixon, Illinois, the home of President Ronald Reagan, also features a Lowell memorial. Many of the people who use Lowell Park know that Reagan worked there as a lifeguard when he was a young man, rescuing some 77 people from drowning. In 1859, Lowell, then working for the Burlington and Missouri Railroad, bought approximately 200 acres about four miles outside of Dixon. He purchased the land partly as an investment, but also because he thought it was so beautiful. In her lifetime, Mrs. Lowell always refused to sell or lease the Dixon property. When she died in 1905, their daughter Carlotta Lowell made arrangements to turn the land into a public park. Miss Lowell commissioned Olmsted Brothers to do a study of the site. Olmsted Brothers evolved from the original company founded by Frederick Law Olmsted, one of America’s most renowned landscape architects. Olmsted designed many prominent projects, among them, Central Park in New York City. On May 8, 1907, a board of five commissioners was appointed and Lowell Park became a reality.

The Massachusetts National Guard Military Museum and Archives in Worcester, Massachusetts, has a copy of the Memorial Hall bust of Lowell. Daniel Chester French gave Humphreys a replica of the Lowell bust in gratitude for his efforts regarding the sculpture. Shortly before his death, Humphreys gave the bust to the Massachusetts Department of the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States. It ended up in a private home and was reclaimed in the 1980s by military archivist James Fahey, who brought it to the archives then located in Natick, Massachusetts. After the Natick facility was closed, the bust was moved to its current site in Worcester, where it is now prominently placed in the Civil War Room.

On June 5, 1890, Major Henry Lee Higginson formally transferred ownership of 31 acres of land to Harvard University. In his donation speech to the Harvard students, he emphasized that the gift was without conditions—but that he would like the grounds to be called “The Soldiers Field” and be “marked with a stone bearing the names of some dear friends—alumni of the University, and noble gentlemen.” Higginson, who founded the Boston Symphony Orchestra, acknowledged that “thousands and thousands of other soldiers deserved equally well of their country, and should be equally remembered and honored by the world. I only say that these were my friends, and therefore I ask this memorial for them.” In a dedication speech, he described each man: James Savage Jr., Charles Russell Lowell, Edward Barry Dalton, Stephen George Perkins, James Jackson Lowell, and Robert Gould Shaw. They were all “men of mark, either as to mental or moral powers, or both, and were dead in earnest about life in all its phases of various talents and they had various fortunes. These men are a loss to the world, and heaven must have sorely needed them to have taken them from us so early in their lives.”

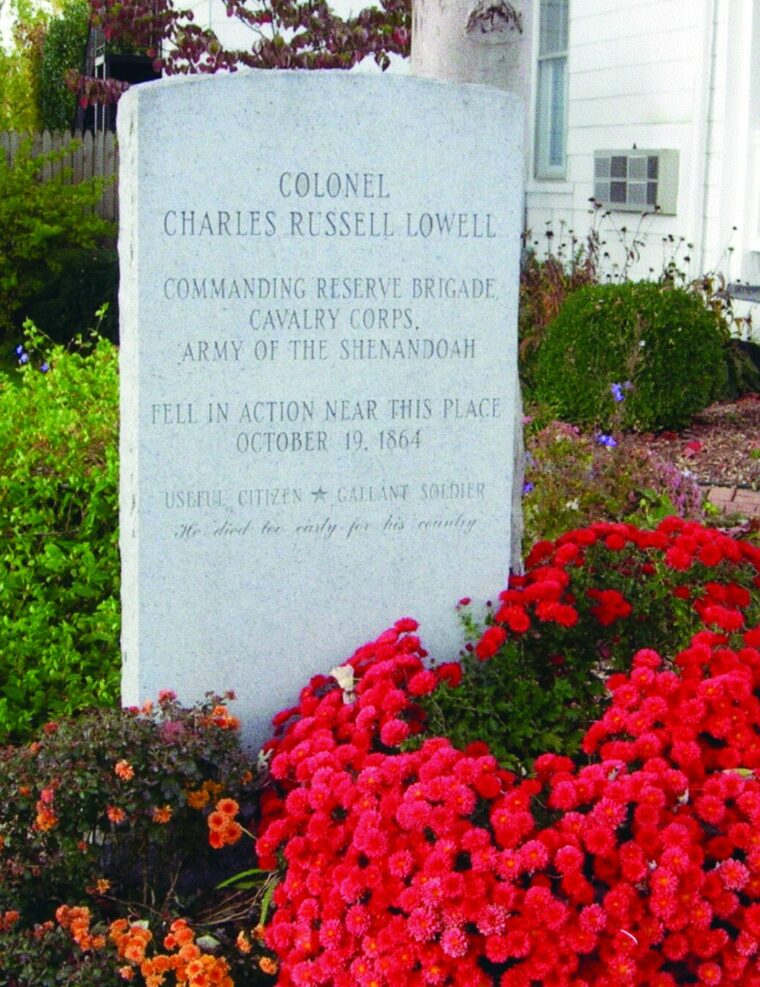

The most recent memorial to Charles Russell Lowell is located beside the Wayside Inn in Middletown, Virginia, not far from the site where Lowell died. A simple granite monument honoring Lowell was placed there in 1990.

It was a tragedy that such a remarkable man as Lowell was lost in the war. Yet the high standards he set played a part in the lives of unknown numbers of people. Two of the people he most influenced, Henry Higginson and Josephine Shaw Lowell, became noted philanthropists. Unknown numbers of lives were made better by the efforts of these two people, under the inspiration of Lowell. Beginning with the people in his life and progressing to the present day, Lowell’s influence is still playing a positive role in the world.

Special thanks to: Edward Burdekin; James Fahey; Albert H. Gordon; George B. Henderson Foundation; Henry Lee; John Lowell; David Mittell; Dee Morris; Brian C. Pohanka; Anthony M. Sammarco; Wayne Stark; Robert J. Torrez; Staffs at the Arizona Historical Society; Boston Art Commission; Commonwealth Museum; Baker Library, Harvard University; Harvard University Archives; Massachusetts Archives; Massachusetts Historical Society; Massachusetts National Guard Museum and Archives; Mount Auburn Cemetery; Mount Hope Cemetery.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments