By John Walker

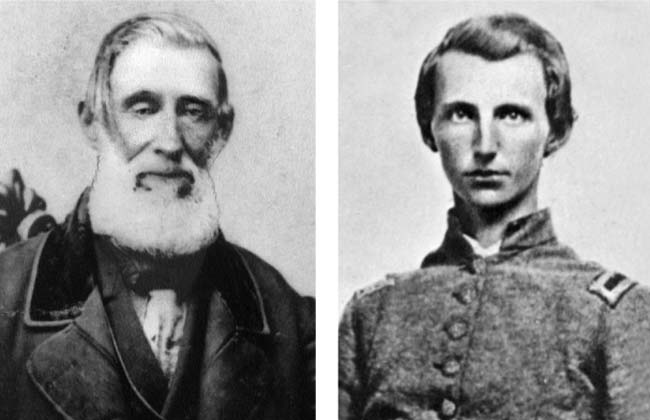

On the morning of November 30, 1864, Fountain Branch Carter, a 67-year-old farmer, planter, and Confederate sympathizer, watched as his front yard in Franklin, Tennessee, filled up with Union soldiers pitching tents and starting campfires. Carter had come into contact with blue-clad troops before, but never an entire army. The Columbia Pike, a macadamized road that ran past Carter’s red-brick farmhouse near the southern edge of town, was also crowded with Union soldiers, wagons, horses, and artillery pieces. More were strung out along the pike as far as Carter could see in the direction of Spring Hill and Columbia to the south. Something bad was coming—and it was coming soon.

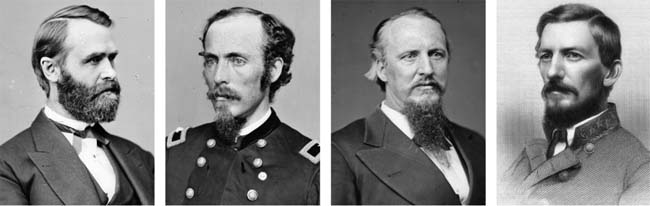

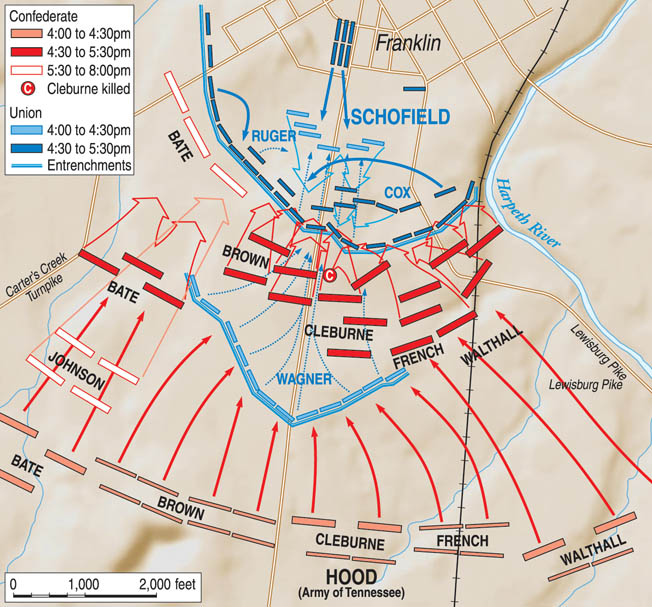

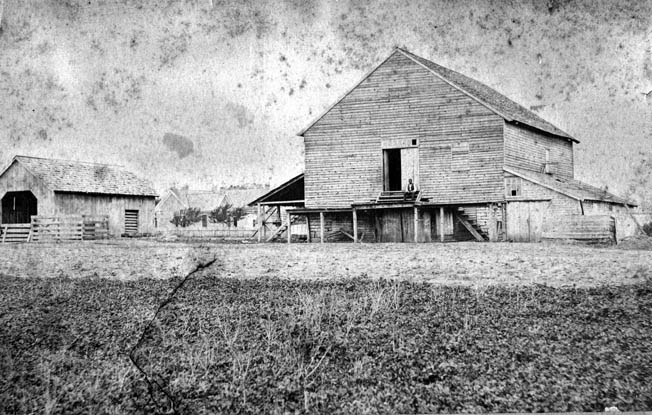

The blue columns swarming the town belonged to Maj. Gen. John Schofield’s Army of the Ohio, consisting of Schofield’s XXIII Corps and Brig. Gen. David Stanley’s IV Corps. Charged by Schofield with preparing a defense of Franklin and the two vital bridges over the Harpeth River, Brig. Gen. Jacob Cox and his staff had roused the Carter family before dawn, taken possession of the house, and turned the parlor into their field headquarters. By noon well over 20,000 Federals had either marched past on the pike or taken up positions in a crescent-shaped line of breastworks running east to west 100 yards south of Carter’s front door. The Carter home, situated just 50 feet from the pike on the west side of the road, occupied a prominent hill that Cox quickly recognized would be the key to his defensive line.

Federal forces had controlled this region of Tennessee for the past two years and had constructed earthen artillery emplacements on the northern bank of the Harpeth, which they dubbed Fort Granger, where Schofield now made his headquarters. While Cox and Stanley conferred with engineers about how best to get 800 wagons and 23,000 troops across the river and onto the road to Nashville by that evening, Carter had the security of his large family to worry about. Moscow Carter, his oldest living son and a paroled Confederate officer, lived with him—two other sons were serving in the 20th Tennessee Regiment, part of the gray host marching north from Spring Hill that morning—along with four daughters, a widowed daughter-in-law, and nine grandchildren under the age of 12.

After Cox informed him that any fighting that day would take place either west or east of the town, should the Confederates attempt a flanking movement as they had the previous day, Carter decided to remain in his home. A frontal assault on the works south of Carter’s home—a deep trench, earthen barriers, abatis, and log entrenchments backed by 60 well-placed cannons in fortified embrasures—appeared unlikely. Carter watched as Cox’s men worked to improve the deteriorating two-mile stretch of works, first constructed by Union troops in the spring of 1863. The works stretched around the southern edge of town with both flanks resting on the Harpeth. To cover the small gap in the line that allowed wagons and the rest of the army to enter the village, a Missouri unit erected a second, fallback line of works on the west side of the Columbia Pike 70 yards behind the main line. The new position was located just behind two outbuildings near the Carter home, and six artillery pieces were moved into position in Carter’s backyard.

After hiding most of his food stores, Carter escorted more than a dozen family members, a group of neighbors, and three of his long-freed slaves down to his large basement, where they remained when the Battle of Franklin erupted above and around them at 4 pm. The roughly two acres taken up by the Carter home and cotton gin would quickly become the epicenter of one of the most savage, costly, and decisive battles of the Civil War.

Hood’s Lost Opportunity

Angry and frustrated after his Army of Tennessee failed to trap Schofield’s retreating army the previous day at Spring Hill, Lt. Gen. John Bell Hood had decided to gamble everything in a last-ditch attempt to overtake Schofield’s two corps at Franklin and drive them into the river. Upon his arrival at Winstead Hill, two miles south of Franklin, at the head of six of his army’s nine divisions, Hood dismissed the concerns of his stunned subordinates and ordered a frontal assault to be launched within the hour. Success could alter the military balance in the western theater of the war and prolong Hood’s desperate 11th-hour campaign to retake Tennessee.

By the fall of 1864, Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman had decisively achieved one of his objectives, the capture of Atlanta, but not the other, the destruction of Hood’s army. Elevated to command after his predecessor, General Joseph E. Johnston, retreated 90 miles from Dalton literally to the outskirts of Atlanta, Hood did what President Jefferson Davis and his advisers wanted him to do—fight. Outnumbered almost 2-to-1 and facing the best commanders the Union could offer, Hood had fought three battles in eight days to defend the city and defeat Sherman in detail. Despite three defeats, Hood managed to extend his lines far enough to prevent Sherman from cutting rail lines into Atlanta, thus thwarting the Union general for five more weeks. Finally, to avoid encirclement, Hood abandoned the city on September 1.

Hoping to force Sherman to abandon Atlanta and fall back to protect his vulnerable single-track line of communications to Chattanooga, Hood led 38,000 Confederates along the railroad into northern Georgia during October, attacking targets of opportunity. Sherman first turned back toward Dalton to deal with Hood, skirmishing over ground captured months earlier, and finally drove the Confederates into Alabama and repaired the railroad. Frustrated, both commanders then opted for radically different plans for their respective campaigns. Sherman cut his supply line, abandoned Atlanta, and set out for the Atlantic coast with 60,000 men, detaching Maj. Gen. George Thomas to Nashville and ordering Schofield to delay Hood’s expected advance into middle Tennessee.

After a costly three-week delay, Hood’s army reached the Tennessee border on November 21 to a fulsome welcome from exiled Governor Isham Harris. Hood’s bold but risky plan to destroy Schofield’s army and retake Nashville was backed by Davis and his principal advisers, Generals Braxton Bragg and P.G.T. Beauregard. With surprising skill, Hood moved quickly and got around Schofield’s small army at Columbia. By late afternoon on November 29, two Confederate corps had descended on Spring Hill and were in excellent position to cut off the Union retreat. In the fog of war, however, the Confederate high command never managed to spring the trap, allowing Schofield’s army to slip by and escape up the pike to Franklin during the night. Hood awoke the next morning “wrathy as a rattlesnake,” in the words of one wary subordinate, infuriated at the lost opportunity. He immediately ordered a full pursuit toward Franklin. At a council of war that morning, Hood excoriated everyone but himself for the debacle, singling out Maj. Gen. Benjamin Cheatham in particular, and by extension two of his division commanders, Maj. Gens. Patrick Cleburne and John Brown.

Frustration Within the Union Command

With Colonel Emerson Opdycke’s brigade of Brig. Gen. George Wagner’s division providing the rear guard, most of Schofield’s army made it to the environs of Franklin by noon and immediately began working on the defenses. Stanley ordered Wagner’s other two brigades, those of Colonels John Lane and Joseph Conrad, about 3,000 men, to occupy an advanced position astride the Columbia Pike a half mile in front of the main Union works, where they were to delay any general enemy advance and then withdraw into Cox’s line when pressured.

Since Wagner’s division had been in the thick of the fighting at Spring Hill, suffering almost all of the Union’s 350 casualties, then had to conduct rearguard actions on the march north, Wagner and other IV Corps officers resented what they felt was Schofield’s preferential treatment of XXIII Corps. Opdycke was angry, as well; while Lane’s and Conrad’s brigades had marched at relative ease on the road to Franklin, Opdycke’s Ohioans hadn’t been relieved during the entire 10-mile march. Upon their arrival at Winstead Hill, they remained in line of battle, facing Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederate troopers, while Wagner’s other two brigades deployed east of the pike on a separate knoll known as Breezy Hill.

When the congestion on the pike cleared, Wagner began leading his division toward the safety of Franklin. Soon, though, a new order from Schofield arrived: Wagner was to hold Winstead Hill with the rear guard until dark “unless too severely pressed.” Following orders, Wagner turned his column about and countermarched but soon observed two huge Confederate infantry columns advancing northward, one on the Lewisburg Pike and one on the Columbia Pike. The latter column was already deploying into a line of battle, their rifle barrels glistening in the sunlight. Without hesitation, Wagner ordered a withdrawal. Lane, Conrad, and Opdycke wasted little time complying with the command.

As he retreated northward, Wagner unilaterally decided that his division would follow the spirit of Stanley’s original orders—to hold back any Rebel advance as long as possible. Halfway back across the two-mile valley, Wagner ordered Lane’s brigade to halt and occupy the southern slope of a flat, open hill on the west side of the road known locally as Privet Knob. About a half mile from Cox’s main line, Wagner halted his leading brigade, Conrad’s, and ordered that commander to take position along a gentle rise of ground east of the pike in a cleared cotton field. Not expecting to fight, Conrad’s men rested without entrenching. When Opdycke arrived, Wagner ordered him to deploy his brigade on the west side of the pike, adjacent to Conrad, to present a two-brigade front.

The headstrong Opdycke ran out of patience. His men had been on arduous rearguard duty since before dawn, he complained, and hadn’t eaten or had coffee all day. Not only that, the position he was told to occupy was untenable, being exposed and without natural cover. Ignoring Wagner’s orders, Opdycke angrily rode on without bothering to halt. When Opdycke’s troops reached the main works, Wagner told Opdycke to deploy where he saw fit and fight in reserve wherever he was needed. Finding the area to the rear of the Union line overcrowded, Opdycke continued north along the pike to the first available open space, located 200 yards beyond the Carter home, where at 2:30 pm his men stacked their arms. Wagner rode to the Carter house, where he was ordered to serve under Cox, the overall commander of the main defensive line.

Unaware that vast columns of gray infantry were even now sweeping over Winstead Hill, Cox merely told Wagner to act according to his earlier orders. Angry and exhausted, Wagner sent word to Lane to withdraw from Privet Knob and take up a position on Conrad’s right in the cornfield. There, he and Conrad were to stay put, fight the enemy if he advanced, and retreat to the main works only if overpowered. Wagner then returned to the safety of the Carter house where he began drinking heavily. Shaken by the unexpected orders to hold this open-field line, Conrad hurriedly ordered his men to entrench.

“We Will Make the Fight”

Hood, meanwhile, had been studying the enemy’s dispositions through field glasses. He believed he had detected a weak spot in the Union center where the Columbia Pike bisected the defenses. Having brought the enemy to bay, Hood announced, “We will make the fight.” When Lt. Gen. Alexander Stewart’s corps began arriving around noon, Hood sent them and Forrest’s men on a flanking march east toward the Lewisburg Pike; he had decided to use Cheatham’s corps as his shock troops. At about 2:45 pm the gray columns surged forward, 20,000 strong—young men from every Southern state except North Carolina and Virginia—deploying into lines of battle at the northern edges of Winstead and Breezy Hills in a two-mile-wide front.

The attack would be made from three directions along the major roads: Stewart’s corps up the Lewisburg Pike against the Union left; Cheatham’s corps, with Cleburne’s and Brown’s divisions astride the Columbia Pike, against the Union center near the Carter house; and Maj. Gen. William Bate’s division up Carter’s Creek Pike against the Union right, backed by Brig. Gen. James Chalmers’s cavalry division. Only two six-gun batteries were on hand to contest the Union guns. Hood had weighted the assault columns heavily against the Union left, sending four divisions of infantry and two of cavalry to attack the enemy’s eastern flank from the Harpeth River to the Columbia Pike.

Across the Columbia Pike, on the longer western flank from the Carter house to Carter’s Creek Pike and a bit beyond, Hood deployed two infantry divisions and a single cavalry division. Hood’s last words to his men were, “Drive the enemy into the river at all hazards.” Cleburne, still stung by Hood’s accusation that he had failed to prevent the Union withdrawal the night before, saluted and responded tersely, “General, I will take the works or fall in the attempt.” When his aide, Brig. Gen. Daniel C. Govan, turned to leave, he said, “Well, General, few of us will ever return to Arkansas to tell the story of this battle.” “Well, Govan,” said Cleburne, “if we are to die, let us die like men.” He pulled his sword out of its scabbard.

The Confederate tide was about 100 yards from Wagner’s advance line when the Union men unleashed a volley of musket fire that momentarily staggered the attackers, but due to the unchecked advance of Stewart’s corps on the right, Conrad’s line was soon outflanked and enveloped. Soon, all of Conrad’s and Lane’s men were in full retreat, the attackers pursuing the fleeing Federals as a cry of “Go into the works with them!” was heard along the line. The pursued and the pursuers became so intermingled in a wedge-shaped mass of humanity veering haphazardly toward the gap in the pike that Union defenders in the main works had to hold their fire for fear of hitting their comrades.

The ground in front of the Union parapets was soon covered with dead and wounded from both sides as Cheatham’s attackers poured through the gap at the Columbia Pike on the heels of Wagner’s men, into and over the adjacent breastworks. Hearing shouts of “Rally in the rear!” among Wagner’s retreating officers, many of the men in the frontline brigades of Colonel Silas Strickland and Brig. Gen. James Reilly joined the mad rush for the rear. East of the road, two Ohio regiments, the 100th and 104th, had been posted to support a Kentucky battery’s four rifled guns. With the guns unable to fire into the ranks of Wagner’s fugitives, the drivers fled, taking their limbers and caissons with them, and soon both Ohio units fled as well.

A 200-yard front stretching from the Carter cotton gin to a locust grove west of the pike had been captured and virtually cleared of Union troops. In addition to Lane and Conrad’s 12 regiments, three of Cox’s regiments, plus parts of two others, had been routed, and a wild mob of men and stampeding horses was racing to the rear past the Carter house. A Union officer later recalled, “It looked as though our line had been crushed at the center and nothing could save the little army from destruction.”

From his vantage point north of the Carter home, where his six regiments had taken up position, Opdycke watched as Wagner’s routed men poured back over the works. When he tried to move several of his regiments to the east side of the pike, many of Opdycke’s men misconstrued the movement as an order to advance and rushed forward directly into the confused mob to their front. This initial rush for the works swept through Opdycke’s remaining units like an electric current. The 125th Ohio seemed to hesitate, and Opdycke shouted, “First Brigade, forward to the works!” On horseback, Opdycke drew his revolver and plunged ahead into the fray. After first colliding with the mass of Union fugitives hurtling northward, Opdycke’s men crowded and bayoneted their way into the Carter yard, pressing for the retrenched line west of the pike. There they observed the main elements of Cleburne’s and Brown’s divisions pouring over the low breastwork “like sheep in a wheatfield,” and a vicious hand-to-hand melee erupted. As Opdycke’s troops struggled to drive the enemy back across the retrenchment, the rattle of musketry swelled, great sheets of flame leaping from thousands of muzzles in a continuous roar.

Many of Cox’s and Wagner’s men, having rallied and returned to the fray at the urging of their officers, joined Opdycke’s brigade in and around the crowded Carter yard. Soon the Federal ranks were four or five deep, those in the front rank firing and passing their empty muskets to the rear, where they were loaded and passed back to the front. Unable to stand unprotected in the face of this firestorm, many Confederates ducked back behind the retrenchment while others sprinted back 70 yards to the main Union breastworks. Still others simply dropped their weapons and surrendered. Arriving on the scene, Stanley saw so many gray-clad prisoners moving to the rear that he thought for an instant that the enemy had broken through and routed Opdycke’s brigade.

Attack on the Cotton Gin Salient

Although Opdycke’s countercharge had pushed back the Confederates, repeated assaults mounted by Cheatham’s follow-on brigades, unimpeded by abatis or obstructions, kept the Carter house in the vortex of a firestorm. On the north side of the retrenched line, the men of Opdycke’s, Conrad’s, Lane’s, and Strickland’s brigades fought from behind the low rail barricade and garden fence, while across the Carter garden to the south the Confederates returned fire from the captured main works. The six Napoleon guns deployed earlier, now worked by Opdycke’s men, added greatly to the carnage in the Carter yard; firing from behind the retrenched line, they poured shell and canister into the enemy-held parapet at a range of just 70 yards. By 5 pm, when a short lull in the fighting took place, the Union lines had been reestablished across the 19 acres taken up by the Carter property. As the ferocity of the Confederate attacks ebbed, a new factor in the fighting emerged: the southern location of the Carter cotton gin had become a salient in the main line. This meant that the Confederates occupying the ditch in Strickland’s front, just west of the pike, were advanced beyond the line of the cotton gin, which Cox’s men still held, and were thus exposed to severe enfilading fire from that direction. As Confederate losses mounted, a stalemate was reached around the gap in the works and the Carter house. It seemed likely that the final result would be decided elsewhere.

With Cox in overall command of the Union defenses, Reilly had assumed command of Cox’s division. His brigade and those of Colonels John Casement and Israel Stiles defended the works in A.P. Stewart’s front. Stiles was located on the far left near the river and railroad cut, Casement in the center just east of the cotton gin; and Reilly between the gin and the Columbia Pike. They numbered about 5,000 against perhaps 10,000 of Stewart’s, 1,300 dismounted cavalry under Abraham Buford, and 4,000 of Cheatham’s troops. From the woods near the McGavock mansion close to the Lewisburg Pike, three brigades under Maj. Gen. William Loring now emerged from the trees and attacked the Union left. They had about 1,000 yards to go when 3-inch rifled guns at Fort Granger opened up, followed by the roar of Reilly’s 12-pounder Napoleons. Great gaps appeared in the attacking ranks, so many that not all could be closed up.

From the railroad tracks to the Lewisburg Pike and almost to the cotton gin, a thick abatis lay in front of the assaulting columns, 50 feet from the main line of works. The thorny, shrub-like trees had been chopped off about four feet above the ground by Cox’s men, opening a clear field of fire above while preserving an almost impassable barrier below. Surplus hedge tops had been dragged to other sectors in the line. The attackers struggled mightily to work their way through the thorny palisade, all the while under galling cannon and musket fire. The storm of projectiles coming from front and flank blunted Loring’s thrust in less than an hour. Following brigades were compelled to detour farther toward the center of the field, away from the snarling congestion at the hedges. The ground on the eastern part of the field became a virtual death zone, wrote a Union survivor, one that “not even a rabbit could cross safely.”

Major General Edward Walthall’s battle-hardened division now advanced on Loring’s left, with Brig. Gen. William Quarles’ Tennessee brigade advancing at a full run against Casement’s front, where they came to an abrupt halt at the hedge. Unable to pass through the palisade, they tried futilely to push or pull it aside, all the while making easy targets for Casement’s infantrymen. One company of the 65th Indiana was armed with 16-shot Henry repeating rifles, and soon a dreadful heap of killed and wounded lay in their front, looking like a rail fence that had been toppled over, the bodies lying in a straight line. The remnants of Walthall’s division staggered west toward the cotton gin salient, where Brig. Gen. Charles Shelley’s troops were heavily engaged with Reilly’s brigade.

The Union position there was formidable. Embrasures for two 12-pounder Napoleons of the 6th Ohio Light Battery, commanded by Lieutenant A.P. Baldwin, had been cut in the works near the cotton gin, supported by the 65th Indiana on Baldwin’s left and the 104th Ohio on his right. When Shelley’s men were just feet from the Union line, Baldwin’s gunners opened up with double charges of canister into their massed ranks. Added to the musket fire from the parapet, the storm of missiles was so intense that the attackers seemed to be literally blown away like leaves in an autumn gust. Baldwin later recalled that he could hear two sounds above the roar of battle: the detonation of the charges and the crunching of bones in front of their muzzles.

The slaughter around the cotton gin salient raged on as four reserve brigades of Stewart’s corps, their ranks mostly intact, approached the flaming works. The attackers lost cohesion, however, with converging brigades crowding toward the center of the field before being driven back upon one another. The emergence of multiple gray battle lines resulted in repeated assaults, causing some Union officers to believe that they had endured as many as 13 separate attacks, seemingly by the same Confederate troops. Among Stewart’s displaced brigades was that of Brig. Gen. Francis Cockrell, whose Missouri troops struck the hedge in Casement’s front, then veered west, only to be swept away by the storm of Union fire. Cockrell’s 687-man unit was virtually wiped out, suffering over 60 percent casualties.

Brigadier General John Adams’s brigade was the next Confederate unit to mount an uncoordinated and isolated attack near the cotton gin. It, too, was abruptly halted 50 feet from Casement’s position by the abatis of hedge tops. In an attempt to get his men moving forward again in the smoke and confusion, Adams spurred his mount toward the flaming parapet and urged it to jump the ditch and embankment. Moments later, after the horse crashed onto the parapet, dead, Adams was riddled with bullets and fell, mortally wounded, into the ditch at Casement’s feet. With the cotton gin firmly in Federal hands and ranks of blue-uniformed soldiers firing obliquely westward, the attacking Confederates pressed against the parapet’s outer ditch were slaughtered like sheep. Confederate Brig. Gen. George Gordon, soon to be wounded and captured, called it a massacre, while an Illinois soldier remembered, “I never saw men put in such a hellish position. The wonder is any of them escaped death or capture.”

Captain Carter Dies Near His Family Home

Brigadier General Thomas Ruger’s division of XXIII Corps constituted the main infantry force defending the Union right west of the Columbia Pike, where the cut branches and snarled treetops of a large locust grove south of the Carter house hill provided a crude abatis. Chaos had engulfed Ruger’s units earlier when Wagner’s fleeing soldiers came crashing back through the gap in the works, forcing them back to the retrenched line. Strickland’s men had formed on Opdycke’s right and helped repulse the first attack of Brown’s Confederates. Meanwhile, the 111th Ohio on Strickland’s right fought doggedly and retained possession of the main works adjacent to the locust thicket, withstanding attacks by the brigades of Brig. Gens. States Rights Gist and John Carter.

Although Gist’s charge stalled when it struck the locust grove, the ongoing chaos near the Columbia Pike allowed the attackers to work their way forward through the abatis and up to the main line, where they fought hand-to-hand with the remnants of the 72nd Illinois and 111th Ohio. The 72nd Illinois gave way, but Gist’s brigade didn’t have the strength to do more than hold its position. When Carter’s brigade came up in support, one of Gist’s officers watched as Union musket and cannon fire “tore their line to pieces before it reached the locust abatis.” Shattered, Carter’s survivors sought shelter behind the ditch held by Gist’s men. It was about this time that Captain Tod Carter, an aide to Brig. Gen. Thomas Benton Smith, joined the fray. As an assistant quartermaster, Carter wasn’t obligated to fight, but the sight of Union soldiers in his home and breastworks covering his father’s yard were more than enough motivation. Mounted on horseback, Carter charged into battle near the locust grove and, shot nine times, fell mortally wounded 530 feet from the home he hadn’t seen in three years. He was found the next morning and taken to his boyhood home, where he died on December 2.

Brown soon learned that Carter’s attack had been unsupported on the Confederate left, where Bate’s division hadn’t appeared on the Carter’s Creek Pike as expected. Before he could act to remedy the situation, Brown was seriously wounded, and after he was carried from the field little was done to get the stalled attack going again. Unable to reach their assigned positions before darkness approached, Bate’s three brigades belatedly advanced toward the smoldering locust grove. Bate split his understrength division, sending one brigade west of the Carter’s Creek Pike and himself leading two brigades toward the locust grove. Although Bate’s attackers were few in number, they managed to send the raw recruits of the 183rd Ohio fleeing to the rear. Bate’s troops poured over the rampart, and hand-to-hand fighting ensued, but the arrival of reinforcements added to oblique artillery fire, sending Bate’s men sagging back across the parapet.

Ordered to support Bate’s advance, Chalmers had waited along the extreme western flank all day for the infantry’s arrival. Finally, at 5 pm Chalmers sent his 2,000 dismounted troopers forward, alone, against the right of Brig. Gen. Nathan Kimball’s line. In the face of horrendous fire, they pressed ahead to within 60 yards of the parapet before withdrawing to snipe at long range. On the Confederate right, Forrest’s cavalry had been repulsed as well, north of the Harpeth. Hood had rashly split his cavalry command into segments, and the much-dreaded “Wizard of the Saddle,” defeated as much by the dispersal of his division as by Union cavalry, was relegated to a minor role in the day’s fighting. It probably saved Forrest’s life.

Although by now the issue had long been decided, Hood wasn’t ready to give up the fight. He ordered a night attack by his only available reserve, the 2,700 men of Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s division of Lee’s corps. Lee had arrived at 4 pm and, on Hood’s orders, hurriedly organized a futile advance that went forward without proper guides or any understanding of what sector his men were to assault. A bit after 9 pm, four of Johnson’s brigades advanced toward the center of the field by torchlight; on their left lay the shattered locust grove, on their right the smoldering parapets in front of the cotton gin. Three brigades got as far as the ditches of the outer works, where devastating blasts of musket and cannon fire, as well as enfilading fire from both flanks, halted the assault. Johnson’s troops suffered 587 casualties in less than an hour.

Tennessee in Mourning

As the night turned cold, most of the surviving Confederates abandoned the outer ditches and withdrew to the line occupied earlier by Wagner’s men. By 11 pm, all was quiet, save for the moans and cries for water from the wounded. From the cotton gin across to the locust grove alone, perhaps 5,000 dead and wounded Confederates lay strewn in grotesque bundles. The death toll upon Hood’s field grade officers had now reached unprecedented levels. Of the 24 generals exposed to battle, six were dead or mortally wounded: Patrick Cleburne, John Adams, Hiram Granbury, Otho Strahl, John C. Carter, and States Rights Gist. Four others were seriously wounded, and another was captured. The army’s middle command structure, with 54 regimental commanders killed or wounded, had been shattered as well. The death toll on the Confederate side came to 1,700, a butcher’s bill that one writer said without exaggeration sent “the entire state of Tennessee into mourning.”

Although some subordinates broached the idea of a counterattack for the next morning, Schofield, after being surprised and shocked by Hood’s unexpected movements twice in two days, was content to escape with his army to Nashville. Hood marched his wrecked army to Nashville as well, where he established fortified lines south of the city on December 2, appealing in vain to Confederate authorities for reinforcements and supplies and waiting for Thomas to attack. Hood hoped to defeat his old West Point instructor and pursue the defeated foe back into Nashville and reclaim it for the Confederacy. On December 15 and 16, Thomas counterattacked and routed Hood’s depleted forces, using all his combat arms—infantry, artillery, cavalry with repeating rifles—to win one of the most decisive battles ever fought in North America. The hard-luck Army of Tennessee, what remained of it, fought and straggled its way back across the Tennessee River, hounded by Union cavalry and infantry. Only 18,000 Confederates crossed the river on December 25. Hood resigned in disgrace shortly thereafter.

After burying his son Tod in Franklin, Carter and his family turned to the task of restoring their shattered home and farm and reviving their livelihood. The Confederate government refused to compensate Carter for the considerable damages to his property—the cotton gin and eight outhouses were dismantled for breastworks, the fields were heavily damaged, and the farm was never again as profitable as it once was. Carter sold off much of his 288 acres of cotton and cornfields not long after the war; he died in 1871, and his son Moscow sold the home and farm property in 1896. It had seemed haunted, anyway, after the events of November 30, 1864.

It is the personal stories, like those of the Carter family, that bring the tragedy of the Civil War into poignant focus.