By John E. Spindler

At 1:25 p.m. on May 1, 1982, the Sea Harrier naval jet fighter became the symbol of British resolve. A pair of aircraft flown by Royal Navy Flight Lieutenant Paul Barton and Lieutenant Steve Thomas had received warning that a number of Argentine aircraft were on an inbound path towards them. Radar determined the enemy consisted of Mirage IIIs. These French-built fighters flew faster and carried more weapons than their aircraft. Barton and Thomas were aware that the Mirage III had already been battle-tested, while the Sea Harrier had been officially operational for less than three years.

The British pilots waited for the enemy jets to fire their missiles and turn for home before engaging the now-vulnerable Mirages. Barton pushed his Sea Harrier into a position a mile behind the rearmost enemy fighter, then fired one of his two American-built AIM-9L air-to-air missiles. He tracked the Sidewinder until it struck the Mirage, which exploded in a ball of flame, raining debris into the sea. Barton had just earned the first British aerial victory since the Korean War. Thomas targeted another Mirage with a heat-seeking Sidewinder and fired. This Mirage pilot dove into the clouds and Thomas was unable to pursue to confirm a kill as he was low on fuel and had to return the HMS Invincible.

Later that afternoon, another patrol intercepted a pair of British-built Canberra bombers and downed one to earn the day’s second confirmed kill. To cap the day, another Sea Harrier pilot destroyed a Dagger—Israeli-modified Dassault Mirage 5—that evening. On the opening day of aerial combat in the 1982 Falklands War, the Argentines flew 35 sorties over their newly-captured territory. Four failed to return, with three of them credited to the Hawker-Siddeley Sea Harrier, the world’s only operational naval vertical/short take-off and landing(V/STOL) jet fighter.

The road to that day for Fleet Air Arm’s Sea Harrier had its origins in the Second World War. Germany was among the pioneers of vertical take-off and landing aircraft. The most notable of their experimental craft was the rocket-powered Bachem Ba 349 interceptor. Although its only test flight ended disastrously, this setback did not discourage continued pursuit into the area of V/STOL. For the rest of the 1940s and into the 1950s, various nations explored the field, which resulted in some interesting concepts such as Avro Canada’s VTOL design of the jet-powered “flying saucer” known as VZ-0 Avrocar. Despite all the attempts, the important question of how to produce a vectored-thrust powerplant for a single-engine fighter still evaded aviation designers.

In the mid-1950s, Frenchman Michel Wibault worked on the concept of using a single engine that funneled its thrust into four centrifugal compressors. Rotating the casings of said compressors produced the required vectoring for vertical or short take-off. Having to overcome the issues of a lack of interest for such an engine as well as little funds available for research and development, Wibault eventually met with Bristol Aerospace Engine’s Stanley Hooker. Fortunately, Hooker assigned the task of converting Wibault’s concept into reality to Gordon Lewis. Lewis and Wibault’s combined effort led to a joint patent in 1957 for such an engine. A revised version of this powerplant was designated the Pegasus. From this moment forward, engineers continued to modify the Pegasus in order to increase its thrust output.

The Hawker Aircraft Company welcomed the idea of designing an aircraft to use the Pegasus engine. Eventually becoming Hawker-Siddeley, the company was incorporated into state-owned British Aerospace (BAe) in 1977. In October 1959, the British Ministry of Aviation requested a pair of the experimental P.1127 aircraft. Less than two months after its unveiling at Hawker’s Dunsfold airfield, an important stage in development of V/STOL aircraft was witnessed—the P.1127’s first flight, although tethered, on October 21, 1960. The first conventional flight had to wait until the following March. Despite the project almost being halted more than once, the Royal Air Force (RAF) decided to evolve the P.1127 into a combat aircraft, designated the “Kestrel.”

Powered by a newer, more powerful Pegasus engine, the Kestrel had large swept-back wings, a higher tail and longer fuselage. Development progressed at a quick pace, with the first flight in March 1964. Shortly afterwards it was renamed the Hawker Siddeley Harrier. A contract for the first 60 aircraft was signed in early 1967, leading to another milestone as the first production Harrier took flight on December 28, 1967. Sixteen months later the RAF received its first Harrier.

Due to a number of factors, the Royal Navy initiated studies into a naval version of the Harrier. The results of these reports demonstrated its feasibility after a few modifications. Importantly, the magnesium engine casing had to be changed to aluminum to protect against corrosion from salt water and sea spray. Designed as an interceptor, the naval version would need a larger nose to house the Ferranti Blue Fox radar. Wing pylons were incorporated to carry both RAF and American weapons, crucially the AIM-9 Sidewinder. To provide the pilot with the view needed to land upon a ship, the cockpit had to be elevated 11 inches. All of these alterations caused the Sea Harrier to be heavier than the RAF-used Harrier Gr.3

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) breathed a sigh of relief when the Navy agreed to purchase 3 developmental and 21 production aircraft, designated the Sea Harrier FRS.1 (Fighter, Reconnaissance and Strike) in May 1975. A year later the Navy ordered an additional 10 aircraft and three trainer versions. While Hawker Siddeley worked on fulfilling the orders, another crucial development took place. The design of a “ski-jump”that allowed a heavily-loaded Sea Harrier to perform the short take-offs dictated by the size of a carrier deck. Trials at various angles began in August 1977, and soon this concept was introduced to the Royal Navy’s carriers—though the angle was not uniform, being 7° on the HMS Invincible and 12° for the HMS Hermes.

The debut of the FAA’s newest aircraft took place in front of an audience at the 1978 Farnborough Air Show, capturing the public’s interest. On June 18, 1979, the Sea Harrier formally entered service with what would eventually be the 899NAS (Naval Air Squadron). The number of Sea Harriers (nicknamed “Shar” by its crews) ordered, allowed for two more squadrons to be formed—the 800NAS and 801NAS. A fourth squadron, the 809NAS, was quickly formed a week into the Falklands War. For 13 years, the world’s first successful V/STOL jet fighter saw no combat action. All of this changed on April 2, 1982, when Argentina occupied the British territory of the Falkland Islands, asserting ownership. Seventy-two hours later, a task force departed on an 8,000-mile journey to reclaim the Falklands.

Under “Operation Corporate,” a hastily-assembled task force would sail from Britain with the Sea Harriers squadrons activated for military operations. Due to the limited space aboard the two aircraft carriers, only 20 Sea Harrier FRS.1s made the initial voyage with 12 aircraft aboard the HMS Hermes and eight on the HMS Invincible. This left 11 “Shars” in England, with two more still in production. One aircraft had been destroyed in December 1980. Author Roy Braybrook in his book about the Harrier and Sea Harrier written shortly after the British victory put forth the theory that if Britain did not possess the Sea Harrier, there would have been no task force—and the Falklands might now be known as “Las Malvinas.”

On the voyage southwards, squadron pilots honed their combat skills and trained using the latest Sidewinder model, the AIM-9L. Each Sea Harrier was armed with a pair of these heat-seeking air-to-air missiles, supplemented by two Aden 30mm cannons mounted beneath the aircraft, each carrying 150 rounds. For attack missions, the “Shar” could carry a 1,000-lb. bomb. Opposing them in the air, British intelligence calculated the Argentine Air Force could muster around 100 operational aircraft, including the Mirage III, the Dagger, various versions of the American-built A-4 Skyhawk, Canberra bombers and the locally-built IA-58 Pucará ground-attack jet. But Argentine aircraft could spend little time over the combat zone, as they had to fly from mainland bases because the Port Stanley runway was too short for all but the Pucarás. Augmenting the Air Force were over a dozen Navy jets, mostly A-4 Skyhawks, but the real concern lay in a small number of Dassault-Breguet Super Étendard which carried the deadly French Exocet anti-ship missile. Some of the FRS.1 pilots already had some experience against the French aircraft with victories over them in combat exercises.

The morning of the first Sea Harrier air-to-air kills witnessed the beginning of Britain’s response. A sole RAF Avro Vulcan bomber targeted the Port Stanley Airport. Only one of the 21 bombs struck the runway, but the British sent a statement. A few hours later, the Sea Harriers engaged in combat for the first time. With 801NAS of the Invincible providing combat air patrol (CAP), the dozen “Shars” from the 800NAS departed the Hermes on attack sorties. Stationed well to the east due to fear of the Exocets, nine aircraft targeted the airfield at Port Stanley with a combination of 1,000-lb. bombs and cluster weapons while three jets dropped cluster weapons on the Goose Green airstrip. All aircraft safely returned. The Sea Harriers eliminated three enemy aircraft with the fourth destroyed by friendly fire. Two days later, another attack on Goose Green brought about the first Sea Harrier loss—Lieutenant Nick Taylor downed by antiaircraft fire. A suspected collision in poor weather downed two more Sea Harriers. The British had now lost 15 percent of their available fighters.

Over the next couple of weeks, the Sea Harriers continued CAP missions, with six or eight planes in the sky at any given time. Although their mere presence turned back a number of enemy sorties, the numbers game came into play as Argentinian aircraft got by them and sunk or damaged a number of British ships. The attack missions exposed a weakness in the Sea Harrier’s design: the lack of chaff dispensers as a countermeasure to enemy missiles. Improvised chaff distributors were fitted on the remaining “Shars.” The first reinforcements of eight Sea Harriers from the newly-formed 809NAS and four RAF Harrier GR.3s were transported via the Atlantic Conveyor.

After three weeks of softening up the Argentines, the liberation of the Falkland Islands commenced with the San Carlos landings on May 21. The day also ended the lull in aerial combat. Sea Harrier pilots used the combination of their superior skills, the FRS.1’s superior maneuverability and the short time the enemy could stay over the islands to down several Argentine planes via AIM-9Ls and 30mm rounds with a kill-list of five Skyhawks, four Daggers and a Pucará. Sea Harriers on CAP frequently arrived back on the carriers dangerously low on fuel. The next few days saw continued aerial action. An Aerospatiale Puma helicopter was listed as a kill after it crashed having lost control in Flight Lt. Morgan’s wake. But the British did not have everything go their way. Another “Shar” was lost when it crashed after take-off and, severely hampered by the lack of an Airborne Early Warning aircraft, a second FRS.1 was lost to enemy air defenses on May 27.

The last aerial battles resulting in Sea Harrier victories occurred on June 8, as British ground forces advanced towards the capital of Stanley. Additional troops were landing at Fitzroy in Bluff Cove. Once again Morgan flew CAP, this time with Lieutenant Dave Smith. Called to the area, both pilots observed a large plume of black smoke and knew something catastrophic had happened. They later learned the landing ship HMS Sir Galahad had been struck while unloading 1st Battalion Welsh Guards and had suffered heavy loss of life. Morgan and Smith jumped on the outgoing A-4s. Closing to 1,200 yards, Morgan launched one of his Sidewinders with a successful ending. He notched a second kill with the remaining AIM-9L. Smith shot down a third, also via missile. These were to be the last aerial victories. On June 14, 1982, Argentine forces in the Falkland Islands surrendered.

Flying over 1,435 sorties, comprising combat air patrol, attack and close air support, Sea Harriers accounted for 22 enemy aircraft and one helicopter without a single loss in air-to-air combat. Argentinian air defenses claimed two Sea Harriers with a further four destroyed in accidents.

Lessons about the Sea Harrier’s limitation were observed and used to improve it. An encompassing upgrade occurred in the 1980s. The resulting FRS.2, later redesignated FA.2 (Fighter and Attack) replaced the inferior Blue Fox radar with the vastly better Blue Vixen pulse-doppler radar. Powered by the latest version of the Pegasus engine, the upgraded Sea Harrier carried four missiles, two on the wing pylons and two on the belly in place of the cannons. The FA.2 became the first non-U.S. aircraft to carry the Hughes AIM-120 AMRAAM (Advanced Medium Range Air-to-Air Missile). Its first flight took place in September 1988. Six years later the British government placed an order for additional FA.2s bringing the total to 47 aircraft with all FRS.1s modified into the new version.

The Sea Harrier FA.2 squadrons saw service in the Balkans, the Middle East and Sierra Leone. On two separate operations in the Balkans “Shars” flew sorties to patrol and enforce No-Fly Zones over Bosnia and then Kosovo. During the latter operation, Sea Harriers flew strike missions which resulted in the loss of aircraft to a SA-7 missile. Sandwiched between the Balkan tours, the aircraft were used to enforce the No-Fly Zone over Southern Iraq. Sent to Sierra Leone from May to June 2000, Sea Harriers operating from the HMS Illustrious were used to intimidate anti-government guerillas.

The only export customer for the Sea Harrier FRS.1 was the Indian Navy. The 25 aircraft and five trainers differed in having a downgraded version of the Blue Fox radar and the ability to carry a different missile package. The few remaining serviceable Sea Harrier FRS.51 retired from Indian Navy service in 2016. By this time, the FAA had long retired its Sea Harriers with its last squadron, 801NAS, disbanded on March 29, 2006.

The naval version of the world’s first successful V/STOL jet fighter, the BAe Sea Harrier, served as Fleet Air Arm’s sole fighter from June 1979 to its retirement from service in March 2006. In the 1982 Falklands War, the “Shar” proved itself, both in the role of attack and as an interceptor. In this latter function the 28 aircraft that served had earned 23 aerial kills without loss in air-to-air combat. Further action in the Balkans, Iraq and Africa only strengthened its legacy. As it is unlikely that Great Britain will develop another indigenous fighter due to cost, author Jaime Hunter rightly titled his book on this aircraft as Sea Harrier: The Last All-British Fighter.

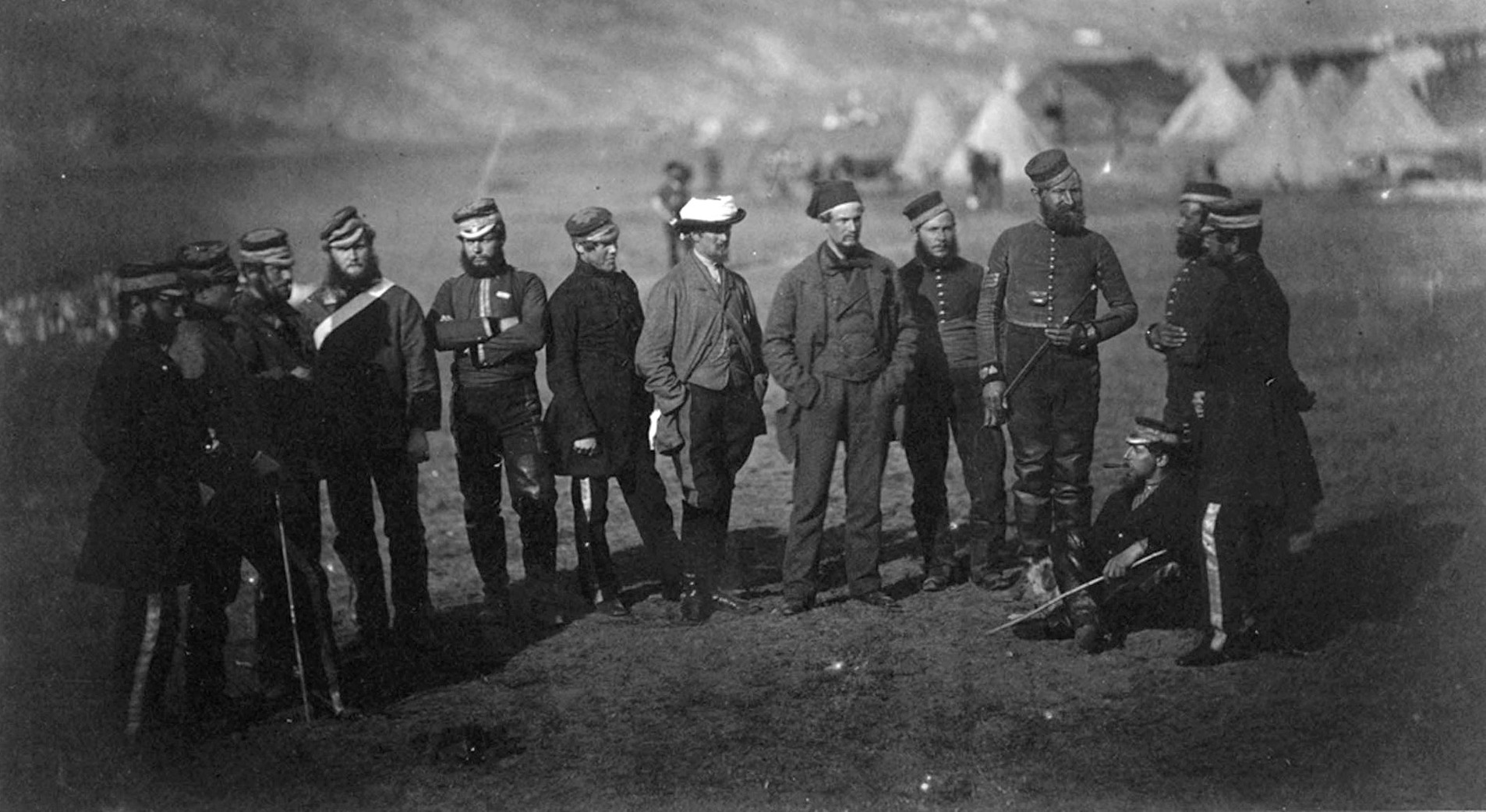

Considering all those wrecked Argentine Pucara aircraft in the background, I think that’s a captured airfield. Maybe Port Stanley?

Thanks for the comment – and you are correct. Unfortunately, a case of transposed captions, now corrected.

Wait one. I look up the German vertical takeoff jet on Wikipedia. This article claims that there was only one test flight. Wiki has a lot more info. This was a disposable, manned, rocket propelled jet.It was verticle launched under ground control until it reached the desired altitude. The pilot took control and maneuvered to attack bombers. Dumped the nose cone cover. There were 24 rockets under the cone. Once the rockets were fired, the pilot disengaged and exited the plane. It crashed and the pilot and the engine were recovered for future use. It was called the Natter. Ten units were deployed with pilots and readied for use. The US military overran the site before any units were launched. The units were destroyed to keep them from being captured. Financed with SS money.