By Peter Kross

By the end of the 19th century, the United States had grown into one of the major players on the international stage. Americans had tamed a continent from the Atlantic to the Pacific, and the mighty industrial engine of the country was making the nation increasingly self-sufficient and self-confident as it looked across the oceans toward the rest of the world.

In 1898 the United States rushed into war with Spain, which leaders in Washington saw as continuing to interfere in Cuba and other parts of Latin America. In hindsight, the Spanish-American War might have been avoided except for the jingoistic American press, which was clamoring for hostilities to start in the wake of the mysterious sinking of the USS Maine in Havana harbor on February 15, 1898, an event that is still being debated today. (Most experts believe the ship was the victim of a boiler-room explosion, not deliberate Spanish sabotage.)

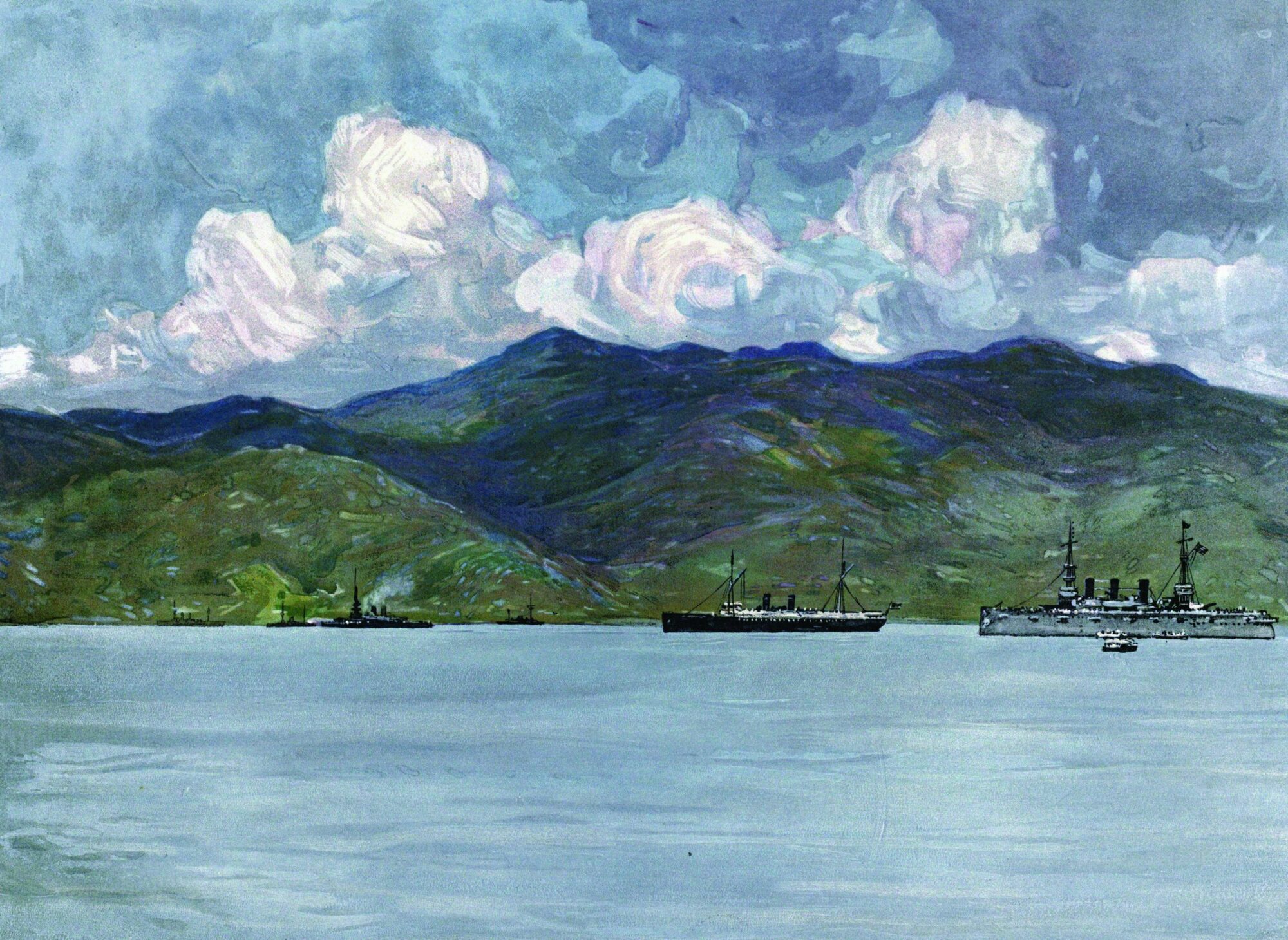

The war with Spain was fought on two different fronts. American troops gathered in convoys off the coast of Florida and stormed the beaches of Cuba, inflicting and taking casualties from Spanish troops as well as from indigenous tropical diseases that felled many more American troops than enemy bullets. In the Pacific theater, the U.S. Navy under Admiral George Dewey decisively bested the Spanish fleet near the Philippine Islands. They were aided by agents of the Office of Naval Intelligence who supplied the Navy with important information on Spanish maneuvers.

As the opposing armies and navies battled with conventional forces, Spain began a covert espionage operation in Montreal, Canada, in an effort to undermine American war efforts. Before the war was over and the ring was eventually shut down, the United States Secret Service would penetrate the operation, conduct “black bag” jobs against the Spanish in Montreal, spy on innocent American citizens, and write forged letters—purportedly authored by Spanish agents—whose sole aim was to create a war cry within the United States.

John Wilkie Takes on the Spy Ring

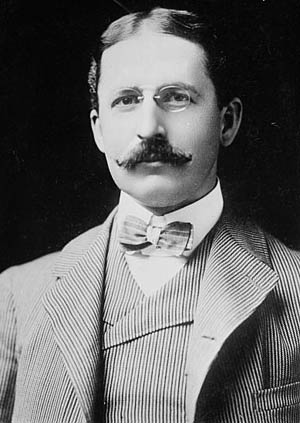

The man who would take on the job of investigating the Spaniards’ Montreal spy ring was John Elbert Wilkie, chief of the American Secret Service. Wilkie, born in Elgin, Illinois, in 1860, began his professional career as a police reporter and business columnist for the Chicago Tribune. After joining the Treasury Department, Wilkie’s first job was to stop a large counterfeiting ring that was changing $1 bills into $100 bills. In the wake of the scandal, the U.S. government was forced to recall all the bills then in circulation. Wilkie worked closely with a Pittsburgh man named William Burns to run a very convincing sting operation that was right out a Hollywood script. In time, they were able to arrest the entire forgery gang.

In the wake of Wilkie’s success in breaking up the counterfeiting ring, Treasury Secretary Lyman Gage promoted him from an ordinary agent making $7 per day to the chief of the Secret Service with a salary of $3,500 per year. With the outbreak of the Spanish-American War, Wilkie was tasked with the job of investigating Spanish covert actions in Montreal. The Spaniard at the center of the Montreal spy ring was Ramon de Carranza, a lieutenant in the Spanish Navy. When the war broke out, Carranza was assigned to the Spanish embassy in Washington, D.C., where he served as a naval attaché. Then and later, most nations assigned naval attachés as a cover for their true profession—that of spy. Carranza relished his new position as an undercover operative and took on the Montreal assignment with near-religious zeal.

Carranza’s Network of Assets

Carranza had a large number of assets he could use inside the United States, drawing on the immigrant Spanish communities in such cities as Tampa, Key West, New Orleans, and Mobile. The Secret Service received a report that pro-Spanish activists in those cities had obtained money to purchase a gunboat for Spain, as well as to carry out reconnaissance work targeting American naval facilities along the Atlantic coast. Secret Service operatives in the field also received information that Spanish spies had been seen as far west as San Francisco, scouting military facilities in the Bay Area. The intelligence service confirmed reports that the minister of the Spanish admiralty, Segismundo Bermejo, had given the order to destroy American naval facilities on both coasts.

Wilkie’s men knew the Spanish were up to no good when, only a few days before war was declared, the Spanish ambassador to Washington, Luis Polo y Bernabe, packed up and left abruptly for a presumably safer haven in Montreal, away from the prying eyes of American agents. Unbeknownst to him, U.S. Secret Service personnel were already watching closely as the ambassador and his entourage arrived in Montreal.

Montreal seemed like a perfect place to establish an elaborate espionage network. The city had a first-class rail system that allowed easy access into and out of town, and it also offered unrestricted ocean access across the Atlantic to Europe. In addition, the Spanish had a long-standing consulate-general office in Montreal from which they could conduct illegal affairs without unwanted interference from the scrupulously neutral Canadian government.

Carranza Places his Agents

After getting settled in the city, Carranza moved his headquarters to the Windsor Hotel, where he thought he would have a safe place to pursue his covert actions. He was unaware that a number of American Secret Service agents, as well as a few inquiring reporters, were also in residence at the Windsor and were literally tripping over each other in the halls.

To mislead the Americans, Carranza and a number of other high Spanish officials left Montreal, supposedly on their way to Liverpool, England. As their ship headed down the St. Lawrence River, however, a few men, including Carranza, got off the vessel and made their way back to Montreal. Carranza set up his new base of operations at a house on Tupper Street. Carranza was justifiably upset when inquiring Canadian newspaper reporters publicized his return to Montreal. Another person who saw Carranza at his Tupper Street address was an American Secret Service agent known only as “Tracer.”

Two Agents Captured

The first undercover agent that Carranza sent to the United States for espionage purposes was an English immigrant named George Downing. Downing had previously served aboard the USS Brooklyn as a petty officer, but his true allegiance rested with the Spanish. When Carranza was giving Downing his orders, he did not know that an American agent was in the next room, listening to every word that was spoken. When Downing arrived in the United States, he was immediately arrested while sending a letter to his superiors concerning American naval strength. Downing was later found dead in his cell. When Carranza heard of Downing’s demise, he surmised that the agent “had hanged himself—or else they did it for him.”

In an effort to place spies within the American military, Carranza used the services of Frank Arthur Mellor, who was sent to him by a detective agency in Canada. Mellor, who came from Kingston, Ontario, convinced two men from his hometown to spy for Spain. This attempt at localized recruitment did not work out well. His first recruit, a man named Atkins, was supposed to head to San Francisco, join the U.S. Navy, and report back to Mellor on what he observed. Before Atkins could head across the border, however, he changed his mind and made his way to the U.S. consul general’s office in Kingston, where he told his improbable tale. When Mellor found out what Atkins had done, he beat him to a pulp. To avoid any other incidents, Atkins promptly boarded a ship bound for England.

Not to be dissuaded, Mellor tried to enlist himself at the American army base in Tampa, where troops were preparing to embark for Cuba. The Army refused to allow him to enlist, but Mellor, watching the disposition of troops and ships, sent messages by post to Carranza in Canada. Members of the British intelligence service operating in Canada alerted Wilkie to Mellor’s activities. They gave the Secret Service the phony name that Mellor was using, and more importantly, the number of the post office box where he sent his superiors his secret messages. American postal officials were able to seize one of the letters before it reached Carranza. With the incriminating evidence in hand, American authorities arrested Mellor. Like Downing, Mellor died in jail—supposedly of typhoid fever.

A Black Bag Job

To get the goods on Carranza, Wilkie’s men undertook a so-called black bag job targeting Carranza’s residence. The action was an illegal break-in, much like the Watergate affair 75 years later. On May 27, 1898, U.S. agents entered Carranza’s home at 42 Tupper Street while the Spaniard was out having breakfast. They took from his desk a letter supposedly written by Carranza to his cousin, Admiral J.B. Ymay. The letter was sent to Wilkie in Washington via a courier who took it as far as Vermont. One week after receiving the letter, Wilkie gave it to the New York Herald, while other copies were sent to the U.S. State Department and the British government.

Upon seeing the letter in print, Carranza immediately charged that its contents had been forged. Carranza was subsequently arrested and in turn sued Joseph Kellert, chief of the Metropolitan Detective Agency in Montreal, for false arrest. He accused Kellert of stealing the letter. The Carranza letter caused a large diplomatic stir involving Canada, Great Britain, the United States, and Spain. The letter was shown to the British ambassador in the United States, Sir Julian Paucefote, who in turn sent it to Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain. All this took place amid legal haggling over whether or not to deport Carranza from Canada.

Ambassador Paucefote met with Wilkie along with another man named Calderon Carlisle, who was a legal adviser to the British embassy in Washington. Carlisle, who was fluent in Spanish, verified the authenticity of the letter. But the matter was far from over. On June 11, the governor-general of Canada, Lord Aberdeen, officially asked the Spanish government to recall Carranza to Spain. The Spanish government refused to go along with the request, saying that Carranza was an innocent victim of an American-Canadian plot. In the end, Carranza, as well as Captain Juan Du Bose, who had served as the chief attaché at Spain’s Washington embassy, quietly returned home.

A Nation Embarrassment and a Blueprint for Covert Affairs

In 1899, a year after the end of the Spanish-American War, the final chapter to the Carranza letter was finally revealed. It proved to be a huge embarrassment to both Wilkie and the Secret Service. The Montreal Star wrote an article on the activities of one George Bell, a Canadian citizen who made an incredible allegation. Bell said that he had broken into Carranza’s Tupper Street residence, stolen the letter, and given it to Wilkie. Bell said that Wilkie had used a forger to falsify the letter. Bell said he was telling his story because Wilkie had failed to pay him the full amount owed, giving him only $50 of the $1,000 he had promised to deliver.

The newspaper published both versions of the letters. The American press soon picked up the Montreal Star’s version; reaction was swift. Soon there was another unexpected twist. Ralph Redfern, who was employed by the Secret Service in its Boston office, said that he, not Bell, had pilfered the letter from Carranza’s residence. Redfern claimed the original letter, proving American allegations, was on file at Secret Service headquarters, but over the years it mysteriously disappeared.

In the wake of the Carranza affair, Wilkie and the Secret Service took a hit in the press for the way the agents had conducted themselves at the time of the Tupper Street break-in. The Secret Service was damaged even more when its agents failed to protect President William McKinley from an assassin’s bullet on September 6, 1901, at the hands of anarchist Leon Czolgosz while the president was attending a trade show in Buffalo, New York. The Montreal spy case was promptly forgotten, but over the years it would become apparent that the resourceful Wilkie had set the blueprint by which American intelligence agents would function, at home and abroad, in the modern age.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments