By Peter Harrington

One of the great tenets of 19th-century historical painting was the idea of plein air art, which called for “truth, naïveté, simplicity, and the impression of the moment,” and insisted that “the soul of the picture is the event, and that the various hats, buttons, bows, spurs, and straps of the costume are not the most important elements.”

Adolf von Menzel, the great German historical painter of the era, was a keen disciple of this thesis, recognizing the artistic value of the inner relation of one figure to another. Menzel built his reputation on paintings depicting the victories of Prussian ruler Frederick the Great, even though he never personally experienced warfare himself. Menzel’s soldiers were real, with a spirit in their action that was the result of countless hours spent working tirelessly on figure studies. In 1866, Menzel traveled to the battlefield of Königgratz (Sadowa) to reassure himself of the accuracy of his previous historical battle pieces. When he saw the dead and mutilated corpses of Austrian and Prussian soldiers lying on the field, he felt satisfied that he had captured the authenticity of battle in his paintings.

Contemporary artists of historical events are confronted with the similar challenge of creating impressions of events that occurred well beyond anyone’s living memory. The modern battlefield offers few clues as to what combat was really like in say, 1805, so the painter has to delve into the available visual clues and written testimonies. This is painstaking work that requires endless hours examining historical artifacts such as weapons, uniforms, and accoutrements, along with reading personal narratives and reviewing paintings and prints from the period, before the first preliminary pencil outlines can be attempted. If the artist is fortunate, he may get to visit the actual scenes of combat, albeit much changed over time. Countless sketches follow, all frequently altered and revised as new information emerges. The next step is to create small oil studies that will provide a sense of scale and show the artist how the overall composition will fit into the larger canvas. The finished painting might not appear for months—sometimes years—after the original conception.

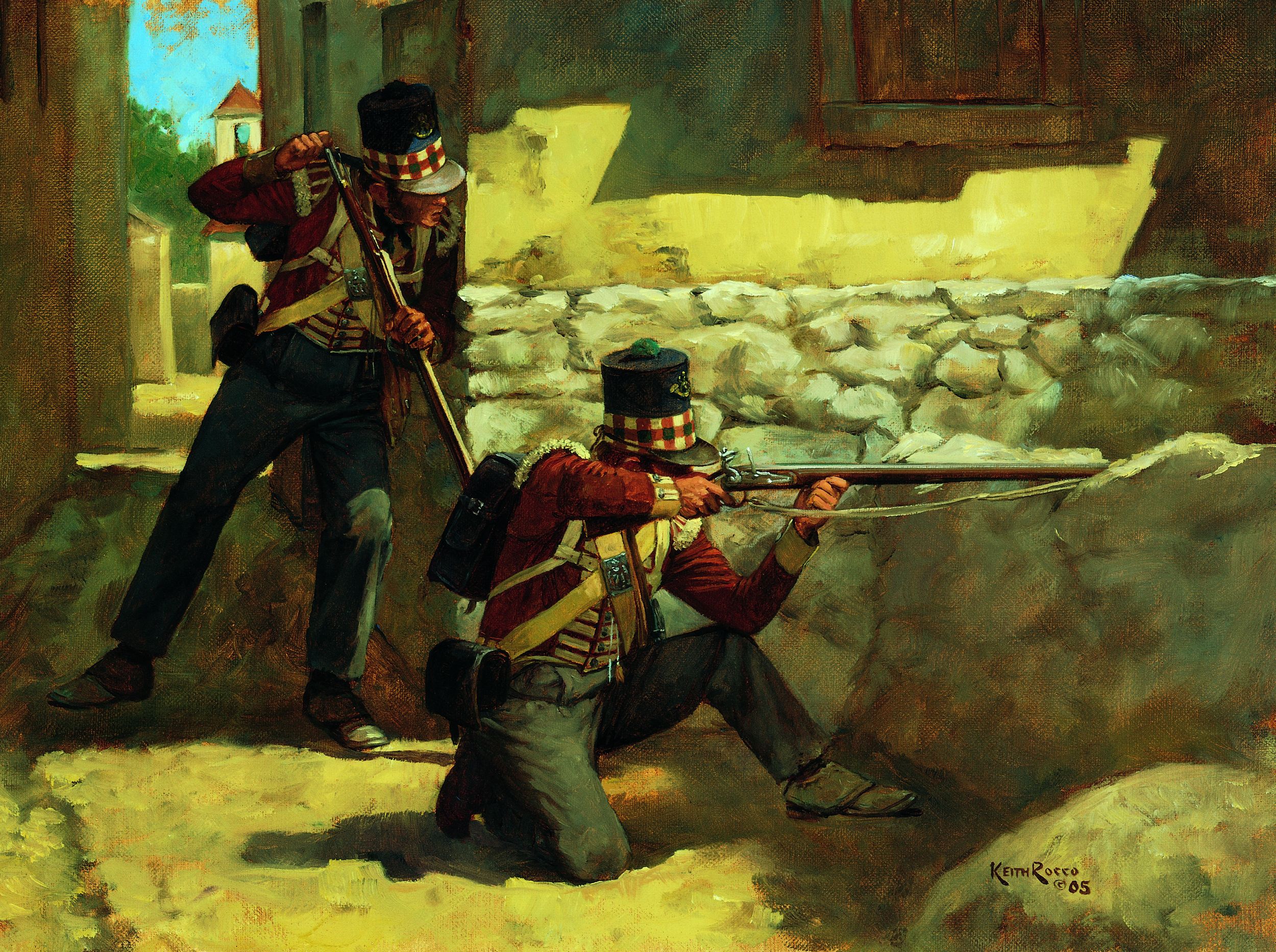

One such scrupulously authentic painter is Virginia-based artist Keith Rocco, best known for his fine renditions of the wars of Napoleon and the epic Civil War battles between Robert E. Lee and Ulysses S. Grant. Rocco’s canvasses can be found in many major collections in the United States and abroad. The National Park Service, the United States Army, state and city museums, and historical societies have all acquired original Rocco paintings, some of which are on a grand scale. His pictures have been profiled in numerous books and magazines, and his prints hang in many private homes.

With his renditions of the Napoleonic period, Rocco is continuing a long tradition of artists who have been attracted to the savage wars of empire that raged across Europe from 1793 until 1815, a period which, according to Rocco, offers one of the widest spectrums of color for an artist to use. “First and foremost I am a painter, and composition and color are still the foundation of any successful painting,” he says. “These particular periods offer me many opportunities to challenge myself artistically and a great diversity of color palettes to choose from.”

French Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte encouraged painters to record his victories, and the famous depiction of the 1807 Battle of Eylau by Antoine Jean Gros was the result of a national competition held in France for the best depiction of the event. Two decades after Waterloo, King Charles X commissioned paintings of Napoleon’s battles to adorn a battle gallery at the Palace of Versailles. While the emperor and his marshals were being lauded on canvas, the experiences of the common French soldiers were being portrayed more humbly in countless lithographs from the pencils of Horace Vernet, Hippolyte Bellangé, Auguste Raffet, and Nicolas-Toussaint Charlet.

By the second half of the 19th century, paintings of the Napoleonic Wars were commonplace on the walls of salons in Paris, alongside scenes from contemporary wars. The artists of these masterpieces are familiar to scholars of military iconography. Edouard Detaille, Alphonse De Neuville, and Jean Louis Ernest Meissonier, for example, were the leading proponents in creating a visual record of Napoleon’s armies and enemies. Rocco’s name often appears alongside such stalwarts, and he is quick to point out that these artists were his inspiration as he labors to create modern impressions of the same era. That these painters and others were concerned with the plight of the common soldier strikes a sympathetic chord with Rocco, who often focuses on the individual in many of his smaller figure studies.

While Rocco pays close attention to detail in the uniforms, accoutrements, and equipment of the private soldier, such details are secondary to his ideals. On this point, he is explicit. “There is a painting movement today that puts the emphasis on details and to a lesser degree emphasis on the composition,” he notes. “The painting becomes a two-dimensional museum of artifacts, where a real museum or a good reference book does a far superior presentation. It is exhausting for the viewer because the eye has no idea where to rest or what is the central focus.”

For Rocco, composition and movement are the keys to lasting art. A glance at the artist’s numerous renderings of the Napoleonic Wars reveals a rich assortment of scenes and subjects. Individual soldier studies figure prominently in Rocco’s oeuvre. We see a French hussar of the 7th Regiment leaning against a wall in Egypt during the campaign of 1799. As he smokes a pipe, local people climb nearby steps. From the same campaign is an interesting vignette depicting French artillerymen seeking shade from the glaring sun beneath a sheet attached to one of their cannons, parked near the ruins of an ancient temple.

At the other extreme, weatherwise, was the calamitous campaign in Russia in 1812, and in a scene with the fitting title of White Misery, Rocco depicts Russian infantry trying to advance while shielding themselves from the bitter cold and snow. Soldiers have wrapped scarves around their mouths, while their officer advances with sword in hand, head lowered. To understand what it felt like to be one of the soldiers fighting in such conditions, Rocco turned to the memoirs of Captain Jean Coignet, who described the hopelessness and suffering of the French troops. Another contemporary observer, British General Richard Bourke, wrote of a “rabble of dying men [who] walked from Orsha to the Berezina like a funeral procession … feeling the seeds of death in one’s enfeebled body.”

While French troops were struggling in Russia, other units of the Grande Armée were fighting on the Iberian Peninsula in a bitter conflict involving extensive guerrilla tactics. Once again, Rocco drew his inspiration from contemporary memoirs to conjure images of non-conventional fighting. In one affecting example, The Last Cartridge, vultures circle above a French wagon surrounded by five bodies, while the perpetrators of the deadly ambush, Spanish guerrillas, approach the scene warily.

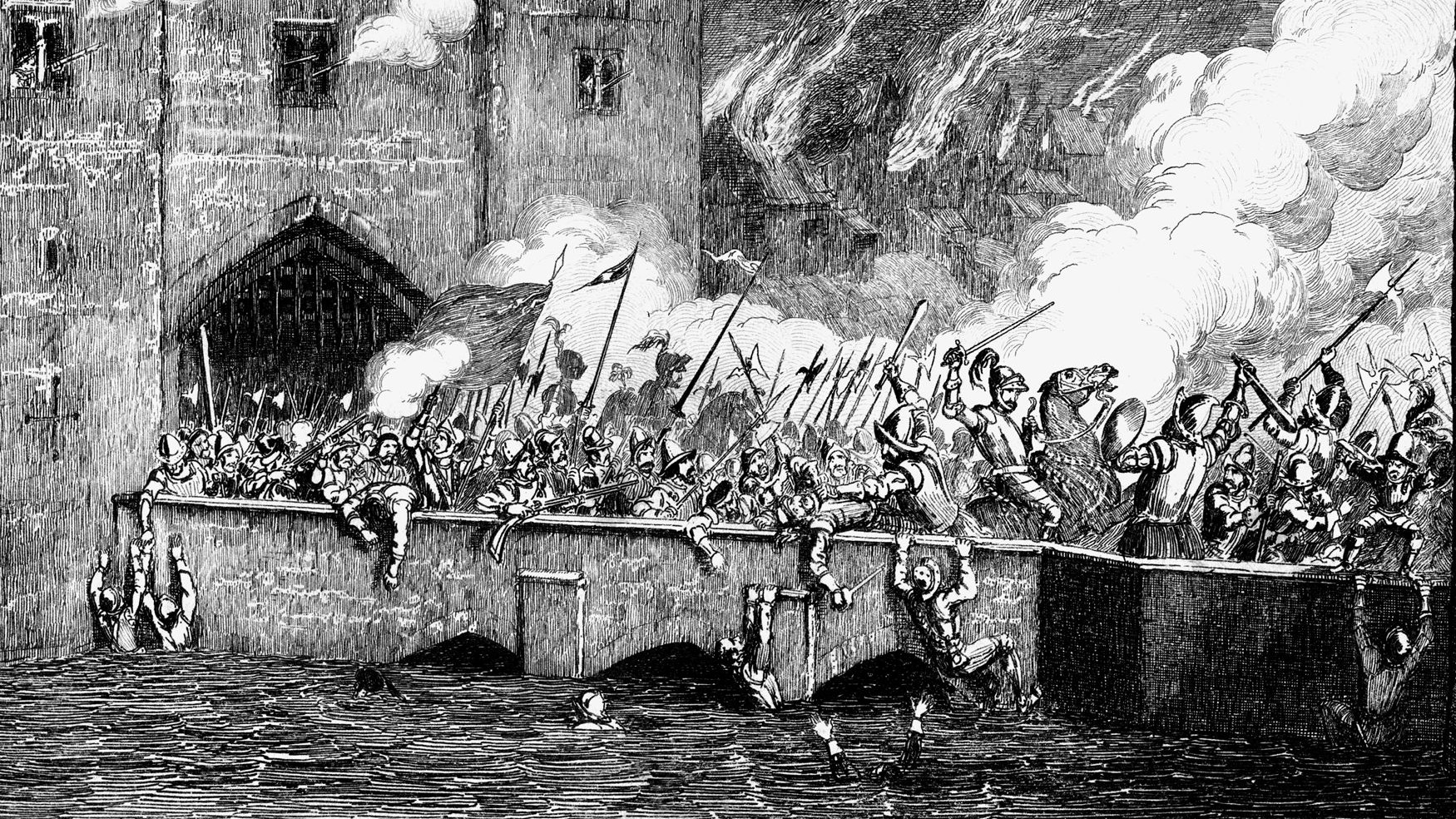

In many of Rocco’s battle tableaux, one is reminded of other great military artists who went before him. His painting of a house at Mockern in 1813, showing Prussian infantrymen firing through the door and window, immediately brings to mind De Neuville’s well-known Franco-Prussian War piece, also entitled The Last Cartridge, while the wonderful animated scene of French troops breaking through the large wooden gates of Hougoumont at Waterloo on June 18, 1815, is reminiscent of the 1903 painting by Scottish artist Robert Gibb. The influences of other late 19th-century battle painters such as Carl Röchling, Ernest Crofts, William Barnes Wollen, and Americans Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth can also be detected in his works. But while readily acknowledging such inspiration, Rocco is less influenced by their subject matter than by their compositional and painting styles. Tribute to Caesar, 1813, which shows a squadron of Polish lancers riding past Napoleon seated on his white horse atop a rise, is the artist’s personal homage to Meissonier and the latter’s great canvas of the Battle of Friedland.

While Rocco has personally inspected the battle sites at Waterloo, Ligny, and Quatre Bras, his emphasis is not on the appearance of the physical landscape, but rather on the human drama that occurs when men are facing death. Consequently, many of his paintings focus on the moment, the incident. He has a special empathy for the rank and file, for the underdog soldiers who willingly follow others into battle—often despite the likely losing outcome. The artist involves his audience in the drama by drawing them into the action to feel the tension, anguish, and stress of battle. We can smell the gunpowder, the mud, the stench of death, the screams of pain, and the thud of galloping horses racing past.

War is never clean, and Rocco effectively creates an atmosphere of the dirty and chaotic horror of Napoleonic warfare. The armies that fought across Europe in the late 18th and early 19th centuries wore some of the most colorful and elaborate uniforms ever designed. Yet each soldier was issued only one uniform and had to wear it on campaign, in battle, on the march, and even to sleep. The improbably crisp uniforms seen in contemporary prints of the period did not stay that way for very long. They soon became ripped, soiled by dirt, sweat, smoke, mud, powder stains, and blood. Rocco is acutely aware of this and paints accordingly. In his piece showing combat outside a building during the Battle of Aspern in May 1809, the once lily-white uniforms of the attacking Austrians are stained and muddied.

When Detaille was creating his masterpieces, he worked in an enormous studio crammed full of uniforms, manikins, weapons, flags, and military artifacts, while outside he kept cannons and artillery wagons. When he died in 1909, his collection became the basis of the new Museé de l’Armeé in Paris. Old sepia photographs of other military artists in their studios reveal similar assemblages of artifacts and accoutrements. Rocco is no exception—he owns a fairly extensive collection of contemporary Napoleonic artifacts, augmented by a large collection of high-quality costumes based on artifacts and other collections.

Never one to rest on his laurels, Rocco is always searching out new information from museums and archives in order to maintain a high level of accuracy in his pieces. Since the Napoleonic Wars lasted almost two decades, there is a virtually endless supply of subjects for the artist to tackle in the future, as he delves assiduously into the past.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments