By Michael D. Hull

Early on the gray, chilly afternoon of Tuesday, December 26, 1944, a column of mud-stained Sherman medium tanks, armored cars, and half-tracks of the U.S. 37th Tank Battalion halted on a road in southeastern Belgium.

For five grueling days, the battalion—spearheading Maj. Gen. Hugh Gaffey’s 4th Armored Division—had advanced 22 miles in a bid to relieve the besieged town of Bastogne, where the 101st Airborne (Screaming Eagle) Division was making a valiant stand against superior German forces.

The firebrand commander of the U.S. Third Army, Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., had ordered the 4th Armored to “drive like hell.” The tankers had, however, made slow progress, hampered by snow, fog, land mines, shell craters, icy roads, and the German 5th Fallschirmjäger (Parachute) Division. The 37th Battalion was now just five miles short of the objective as its commander, 30-year-old Lt. Col. Creighton W. “Toots” Abrams, Jr. of Agawam, Massachusetts, stood on a hill and gazed north towards Bastogne. He was down to 20 tanks, which he reasoned would barely be enough for one more assault.

Climbing back onto his Sherman—named “Thunderbolt IV”—the lantern-jawed Abrams radioed Gaffey and asked permission to continue the attack. Gaffey telephoned Patton, and a few minutes after 3 PM, Abrams was handed a message. He read it impassively, but his eyes glinted. Sticking a large cigar into his mouth, he clambered into the turret of his tank and radioed to his men, “We’re going in to those people now. Let ‘er roll!”

Supporting artillery pounded the village of Assenois south of Bastogne as the 37th Battalion clanked forward. Followed by the half-tracks crammed with infantrymen, the Shermans rumbled through woods and down a steep hill as dusk began to veil the snow-clad countryside. With Lieutenant Charles Boggess commanding the first nine tanks, the column blasted through Assenois toward the outskirts of Bastogne.

At 4:50 pm, Boggess jumped from his tank when a grinning 101st Airborne Division engineer emerged from a foxhole. The seven-day siege had been lifted, “and as dusk started to come down,” reported a Yank magazine correspondent, “Colonel Abrams rode through—a short, stocky man with sharp features—already a legendary figure in this war.” The historic relief of Bastogne made him an instant hero in the American press.

Abrams and his staunch tank crew wore out seven Shermans, winding up with “Thunderbolt VII” by the time the war had ended in Europe in May 1945. Painted on the side of each was a large white thunderhead pierced by two jagged bolts of red lightning and the name “Thunderbolt.”

The ubiquitous Sherman M4 was the frontline symbol of America’s World War II “arsenal of democracy.” It not only became the U.S. Army’s workhorse medium tank in all theaters of operation from 1942 to 1945, it also saw extensive use by the U.S. Marine Corps as well as by British, Commonwealth, Free French, and Polish Armies. Four thousand M4s were sent to Russia alone through the Lend-Lease program.

Nevertheless, the M4 had many weaknesses: less-powerful guns, a high profile, thin armor, and an alarming tendency to burst into flame when hit. The German panzers consistently outclassed it, but on the plus side, it was easy to mass-produce and handle, speedy and mechanically reliable, and available in large numbers.

Named for General William Tecumseh Sherman of Civil War fame, the Sherman was the successor to the stopgap Grant and Lee M3 medium tanks. After the British Tank Commission made design suggestions in 1940 based on field experience, Lees and Grants were ordered, built, and then used by British and Commonwealth armored forces in the Western Desert. In March 1941, after completing work on the Lee M3 series, the U.S. Ordnance Department immediately began work on a replacement, the Sherman M4.

By April of that year, five tentative M4 designs had been drafted. One was for the medium T6 trial vehicle, which was chosen by the Army’s armored force because of its simplicity. It retained the Lee’s proven chassis, engine, transmission, and lower hull, but it mounted a 75mm main gun in a cast turret with full 360-degree traverse, eliminating the limited targeting ability of the M3’s smaller 37mm sponson gun and reducing the crew to five. The T6 inherited the Lee’s sponson doors, but these were removed by the time the design of the M4 tank was standardized on September 5, 1941. America was at war by the time the pilot model of the Sherman rolled off the assembly line at the British-funded Lima, Ohio, Locomotive Works in February 1942.

Mass production got underway the following month. Besides the Lima plant, the 10 major manufacturers that produced thousands of M4s were American Locomotive Company, Baldwin Locomotive Works, Chrysler’s Detroit Tank Arsenal, Federal Machine & Welder Company, the Fisher Grand Blanc (Michigan) Arsenal, Ford Motor Company, Pacific Car & Foundry Company, Pressed Steel Car Company, and Pullman Standard Manufacturing Company. It was one of America’s many industrial triumphs during the war. At the Fisher tank plant, workers rolled out the first Sherman only three months after ground had been broken.

The original Sherman featured a welded hull, soon replaced by a cast version. The tank weighed between 32 and 35 tons; was 19 feet, 6 inches long; had an armor thickness of 1.5 to 2.5 inches; was armed with a 75mm gun, a 50-caliber Browning machine gun, and two .30-caliber machine guns; had a road speed of 24 miles an hour; and carried a crew of five.

By the time production ended in June 1945, a staggering total of 49,234 Shermans had been built, 21,000 during 1943 alone. This constituted more than half of America’s wartime armor production and surpassed the total combined wartime tank output of Great Britain and Germany. The Canadians also built 188 M4A1s, which they called the Grizzly I.

Sherman tanks arrived in northern Egypt in September as General Bernard L. Montgomery’s revitalized Eighth Army was gearing up for its next major offensive against Field Marshal Erwin Rommel’s vaunted Afrika Monty was glad to receive the “excellent” Shermans, whose 75mm turret guns made them a match for Rommel’s panzers. The M4 received its baptism of fire when British and Commonwealth “ironsides” and infantry surged forward on the night of October 23, 1942, in the Second Battle of El Alamein, the first turning point of World War II. The Afrika Korps fought hard, but it was soon in full retreat.

On November 8, 1942, the Allied invasion of North Africa began. The first use of Shermans in combat by American troops occurred in Tunisia the following month. The M4 was in the thick of the action when the inexperienced U.S. First Army was mauled by the Afrika Korps, and then later as the American forces came of age in the early months of 1943. The tank proved robust, reliable, and easy to handle and maintain on the battlefield. The Sherman’s rubber-block tracks had about five times’ the life expectancy of German steel tracks.

But the Sherman’s limitations came to light dramatically when faced with the enemy’s deadly 88mm flak guns, 20-ton Mark III panzers, 26-ton Mark IV panzers, and 63-ton Tiger E Mark VI tanks. Shermans took terrible punishment in February 1943, when Maj. Gen. Lloyd R. Fredendall’s U.S. II Corps was routed at Sidi Bou Zid and Kasserine Pass, the first major American defeat of the war.

German gunners were quick to discover the thinly armored, gasoline-burning Sherman’s fatal weakness. A single shot glancing off its rear sprocket would turn the tank into a fiery coffin. It burst into flame as easily as a cigarette lighter, gaining it nicknames like “Zippo,” “Ronson,” and “Tommy-cooker” from its American and British crews and their German foes. Such “brew-ups” continued to plague Sherman crews until diesel fuel was adopted for use in the A-2 and A-6 variants.

A Kasserine survivor reported, “Everywhere, the Shermans were rumbling to a stop, taking up the hull-down position and waiting for German tanks to come within range, but the Germans were not doing them that favor. Sherman after Sherman was hit, rocking from side to side with the impact, and almost immediately engulfed in an explosion of smoke and fire as the five-man crew scrambled their way out and doubled for safety, pursued by the angry red hornets of tracer bullets.”

Sergeant James H. Bowser said of his Sherman, “…this is my third tank, although I’ve still got my original crew. We were burned out of the other two. If they were diesels, it wouldn’t have happened, but these gasoline engines go up like torches on the first or second hit. Then you’ve got to barrel out and leave ‘em burning.”

General Omar Bradley reported, “In their first engagement, the American tankers learned that, tank for tank, their General Grants and Shermans were no match for the more heavily armored and better-gunned German panzers. Two years later in the Battle of the Bulge, this disparity had not yet been corrected. Although the Shermans eventually mounted heavier (76 mm) guns, at no time could they engage the enemy’s Panthers and Tigers in a direct frontal attack. But it was in dependability that the American tank clearly outclassed the German. Its powerful engine could always be counted on to run without a breakdown. This advantage, together with our U.S. superiority in numbers, enabled us to surround the enemy in battle and knock out his tanks from their flanks.”

Crew losses mounted, morale declined, and the Sherman “scandal” was exposed later by C.L. Sulzberger in the New York Times. A G.I. was quoted as saying, “The people who built the tanks I don’t think know the power of the Jerry gun. I have seen a Jerry gun fire through two buildings, penetrate an M4 tank, and go through another building.” Despite this, more and more Shermans rolled off the assembly lines and went into action.

By 1943, the Sherman had become the standard U.S. Army and Marine Corps tank. Although it was under-gunned and thin-skinned, it could generally outfight its more powerful adversaries because of superior maneuverability and superior numbers. Despite its shortcomings and crew complaints about its performance against panzers, the M4 constituted a triumph of engineering and mass-production techniques. It used less than half the gasoline of larger tanks, was faster, and had more range. Its tracks lasted for 2,500 miles, while German Panther and Tiger treads were good for only about 500 miles.

The Sherman also had the advantage of being driven and maintained by G.I.s more mechanically experienced than their opposite numbers. Mobile workshops and the recovery of damaged tanks, pioneered by the British in North Africa, meant that half of the M4s put out of action could be repaired and sent back on the line within two days. The Germans and the Red Army frequently abandoned vehicles when they were hit or broke down.

In the Pacific Theater, where the Japanese fought fanatically but were hampered by obsolete and inferior weapons of all types, Shermans clearly outclassed enemy light tanks.

Marines first used Shermans in Operation Galvanic, the November 1943 invasion of the Gilbert Islands. After amtracs paved the way across the fire-swept reefs at Makin and Tarawa, Shermans ground ashore to blast Japanese pockets of resistance. M4s fitted with Mark 1 flamethrowers, which could spew napalm 150 yards, proved particularly effective in destroying gun batteries, mortar emplacements, concrete pillboxes, caves, and coconut-log bunkers. Sergeant Bill Reed of Yank magazine reported from Iwo Jima in February 1945, “The Japs were afraid of our tanks, so afraid that they ducked low in their shelters and silenced their guns when they saw them.”

On D-Day, Shermans rolled across the five invasion beaches and played a major role in supporting the Allied infantry divisions as they fought their way inland. Along with Churchill tanks modified as flamethrowers (or “Crocodiles”), bridge carriers, carpet layers (or “Bobbins”), and recovery tanks, many Shermans involved in the landings also performed special functions. A number of them, fitted with inflatable canvas skirts, were duplex-drive amphibians that could go ashore directly from landing craft. Others were fitted with dozer blades, and still others had been specially equipped to clear mines and other obstacles. The specialized Churchill and Sherman tanks were known as “Hobart’s Funnies” after Maj. Gen. Percy C. S. “Hobo” Hobart, an armored-warfare pioneer who oversaw their design. The Funnies included Sherman “Crabs” fitted with flails to explode mines and “Fireflies” armed with British 17-pound guns. These M4s, particularly the flail tanks, proved invaluable to the British, Canadian, and Free French troops and commandos at Gold, Juno, and Sword Beaches.

Unfortunately, at Omaha Beach, where the U.S. 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions were pinned down and mauled for several critical hours on D-Day morning, the DDs were launched too far out and sank in heavy seas, so only a few made it to shore. The 741st Tank Battalion lost 27 of its 29 tanks. The Funnies, which were effectively neutralizing mines in the other landings, could have minimized the losses on Omaha Beach.

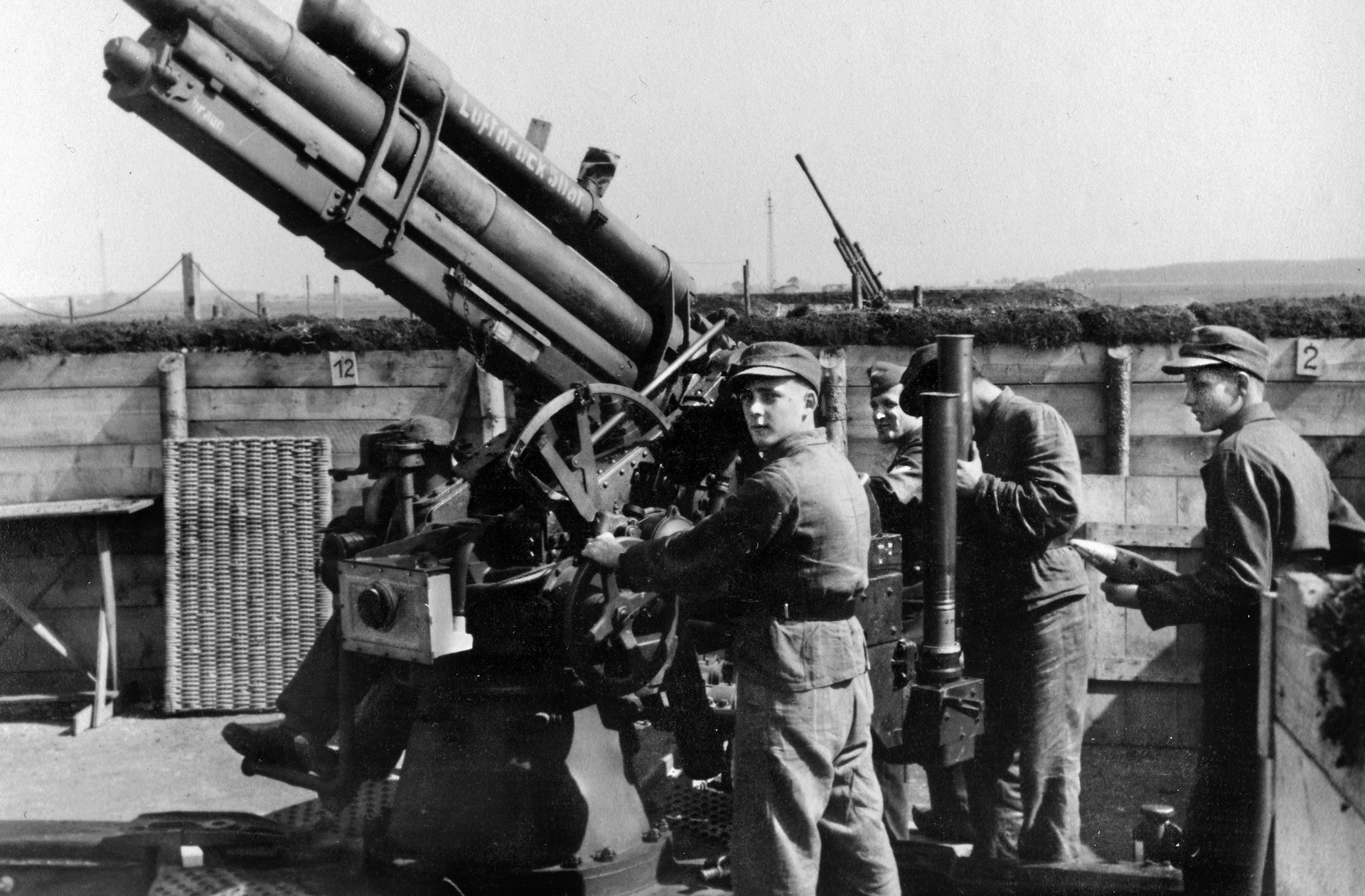

After D-Day, the Shermans forged ahead as the Allied armies broke out of the Normandy beaches and headed inland. By this time, the Sherman lent itself to other uses, including the chassis and hull for the powerful M10 tank destroyer, the 105mm Priest and 155 mm howitzer motor carriages, the British 25-pound Sexton, the Calliope and Whiz Bang rocket launchers, the Skink antiaircraft tank, and a variety of engineer vehicles.

With the Firefly and its 17-pounder, the best Allied antitank gun of the war, the British had for the first time a tank almost equal to the panzers. Until the Comet cruiser appeared, the Firefly was the only British tank capable of engaging the Tigers and Panthers on anything like equal terms.

While British and Canadian units battled the bulk of German armor around historic Caen, the Americans to the west struggled to gain a breakthrough and reach strategic Cherbourg as planned. The terrain, which was ideal for defense rather than mobile warfare, forbade it.

An American breakout depended on their armor being able to move forward, but attempting an offensive in the bocage was risky, costly, and time-consuming, with the infantry denied crucial support. Tankers tried again and again to go over or through the bocage embankments, but they proved virtually impassable to the Shermans. They were not powerful enough to break through the concrete-like earthen barriers, and if they managed to climb the embankments, their bellies were sitting targets for enemy Panzerfausts (antitank guns). The Allied offensive was stalled by the stubborn German defense in the bocage, but American mechanical ingenuity came to the rescue in time for Operation Cobra, the U.S. First Army’s breakout that started July 25, 1944.

Less than a week before the planned launch of Operation Cobra, General Bradley received a telephone call from Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, commander of the V Corps, summoning him to the 2nd Armored. “Bring your ordnance officer along,” said Gerow. “We’ve got something that will knock your eyes out.“

Bradley complied and found Gerow and several staff officers clustered around a Stuart tank to which a crossbar had been welded. Four tusk-like metal prongs protruded from it. Bradley watched as the tank backed off and then ran head-on toward a hedgerow at 10 miles an hour. The tusks bored into the hedgerow, and the tank butted through successfully under a shower of dirt. “It was so absurdly simple that it had baffled an army for five weeks,” Bradley reported.

Within a week, three of every five Shermans and other tanks, dubbed “Rhinos,” had been fitted with the crossbars in time for the breakout. The inventor of the tusked crossbar was 29-year-old Sergeant Curtis G. Culin, Jr., of the 2nd Armored Division’s 102nd Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron. He was awarded the Legion of Merit for his ingenuity. Four months later, after losing a leg in the bloody Huertgen Forest campaign, Culin returned home.

Shermans were the first tanks delirious Parisians saw when Maj. Gen. Philippe Leclerc’s proud 2nd Free French Armored Division fought its way into the Nazi-occupied French capital on August 25, and British- and American-manned M4s rolled through Holland in the ill-fated Operation Market Garden the following month.

Shermans clanked on until the Allied armies finally brought Nazi Germany to its knees in the spring of 1945. The sterling service of the Shermans all the way from El Alamein to Okinawa contributed immeasurably to the Allied victory.

After the war, many armies worldwide used M4s. About 200 later M4A3E8 models were rushed in August 1950 to Korea, where they joined Chaffees, Pershings, Pattons, Walker Bulldogs, and British Centurions in battling Soviet-built T-34s. The sturdy, wide-tracked “Easy Eight”-model Shermans saw considerable action with the U.S. Eighth Army and the British Commonwealth Brigade, proved a match for the Communist forces’ much-feared T-34s. M4s were also used in the Arab-Israeli wars of 1967 and the Indian-Pakistani conflicts.

Supplanted in recent years by such modern behemoths as the American Abrams and the British Challenger and Conqueror, the World War II Sherman has become just a distant name in the history of armored warfare. Yet a few preserved models remain as reminders of their gallant service in World War II and can be seen at Bastogne and other locations, including the famous Bovington Tank Museum in Dorset, England; Sainte-Mere-Eglise, Utah Beach, Juno Beach, Ecouche, and Saumur in France; Wiltz and Ettelbruck in Luxembourg; and Arnhem and Overloon in Holland.