By Lt. Col. Harold E. Raugh, Jr., Ph.D., U.S. Army (Ret.)

Considered the world’s strongest fortress,” writes military and aviation historian C.G. Sweeting, “Sevastopol was a vital port for the Soviet Black Sea fleet, and because of its terrain and the strength of its fortifications, well suited to resist a siege indefinitely.” The course of history and this interesting book by Sweeting show that the Soviet garrison and fortress of Sevastopol held out bravely, but not indefinitely.

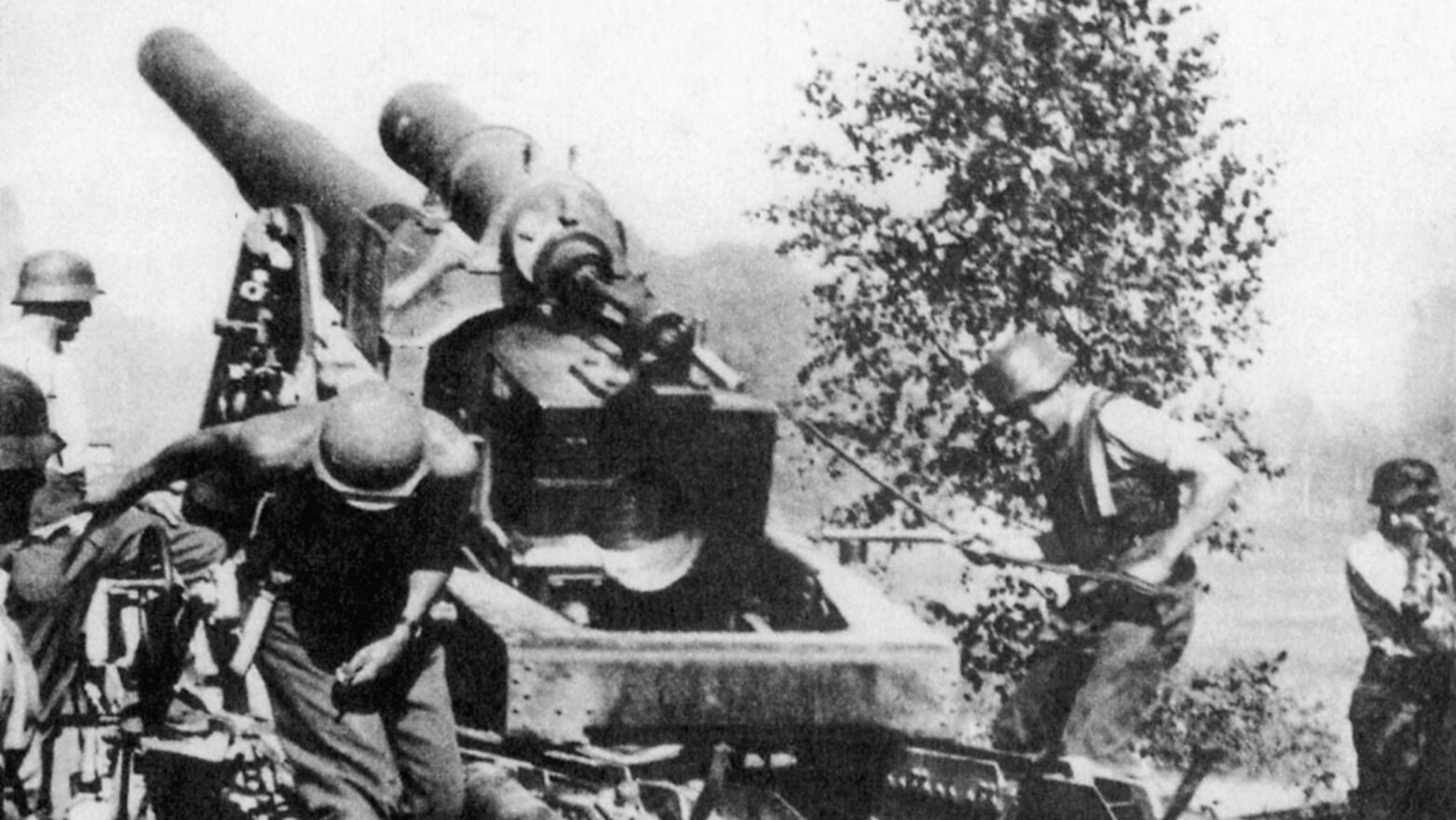

The significant World War II campaign for Sevastopol, little known in the West, is brought to life in this new study. In what is reportedly the first English language account devoted to this important Eastern Front campaign, Blood and Iron: The German Conquest of Sevastopol (Brassey’s, Washington, D.C., 2004, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, glossary, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover), Sweeting chronicles in detail, with numerous photographs, and generally objectively the fierce 1941-1942 German military operations on the Crimean Peninsula that resulted in the capture of the formidable fortress of Sevastopol.

The significant World War II campaign for Sevastopol, little known in the West, is brought to life in this new study. In what is reportedly the first English language account devoted to this important Eastern Front campaign, Blood and Iron: The German Conquest of Sevastopol (Brassey’s, Washington, D.C., 2004, 224 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, glossary, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover), Sweeting chronicles in detail, with numerous photographs, and generally objectively the fierce 1941-1942 German military operations on the Crimean Peninsula that resulted in the capture of the formidable fortress of Sevastopol.

This appealing book begins with an overview of Operation Barbarossa—the German attack on the Soviet Union, which kicked off in June 1941—and the opposing German and Soviet forces, with an emphasis on German airpower. The German Eleventh Army (which included Romanian Army units), commanded by General of Infantry (later Field Marshal) Erich von Manstein, began its attack on the Soviet defense line across the Perekop Isthmus, the gateway to the Crimea, in October 1941.

After days of frantic fighting, the German-Romanian army broke through the Soviet defenses and surged toward Sevastopol and Kerch. As von Manstein’s force was attacking Sevastopol in December 1941, the Soviets audaciously conducted amphibious landings on the Kerch Peninsula to the German rear. Flexible and innovative, von Manstein adroitly cleared the determined Soviets from the Kerch Peninsula, although this diverted precious resources from German offensive operations at Sevastopol. An intense five-day German artillery bombardment by 576 guns and numerous aircraft began on June 5, 1942. After savage fighting, the Germans captured the “impregnable” fortress of Sevastopol on July 4, 1942.

The main body of this slim volume chronicling the Sevastopol campaign consists of 89 pages. This is followed by five appendices, some of which appear to have been extracted from official British and American military manuals. Appendix A is 275-victory Luftwaffe ace Lieutenant General Guenther Rall’s short “Crimean Combat Report.” Other appendices describe and compare “Ranks, Uniforms, Insignia, [and] Medals,” as well as various German and Soviet weapons and artillery pieces. Notable among the latter was the incredible 800mm German siege gun named Dora, the largest artillery piece ever constructed.

Sweeting’s Blood and Iron: The German Conquest of Sevastopol, is valuable in bringing the story of this epic campaign to the attention of Western readers. This volume deserves to be on the bookshelves of Eastern Front historians and enthusiasts.

Recent and Recommended

Recent and Recommended

Combat Officer: A Memoir of War in the South Pacific, by Charles H. Walker, Ballantine Books, New York, 2004, 239 pp., illustrations, maps, $6.99, softcover.

“As full daylight came the Japanese disaster became apparent,” declared U.S. Army Lieutenant Charles H. Walker shortly after his baptism of fire on Guadalcanal in October 1942, as “hundreds of bodies lay to our front in the open grass.” This was one of many fierce engagements that Walker fought in the Pacific during World War II. Walker was a lieutenant (and later captain and major) in the 164th Infantry Regiment of the North Dakota National Guard.

The unit was mobilized in 1941 and in 1942, when sent to reinforce the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal, the 164th became the first Army unit to take offensive action against the Japanese. Originally a part of Task Force 6814, the 164th Infantry became a regiment of the Americal (“Americans in New Caledonia”) Division when it was formed in 1942. The 164th Infantry spearheaded the Americal Division’s island hopping from Guadalcanal to Bougainville and the Philippines, where it trained for the planned invasion of Japan.

Walker, as a platoon leader, company commander, and battalion staff officer, fought throughout these ferocious campaigns. His brutally candid and keen observations of fighting a determined foe in dense, malaria-ridden jungles dominate this book. In addition to his hatred of the Japanese, Walker reveals his resentment of West Point graduates, hypocritical higher staff officers, and rear echelon support soldiers. This action-packed memoir details the challenges of small unit leadership in combat and the horror, savagery, and chaos of war.

In Brief

In Brief

Forgotten Voices of World War II: A New History of World War II in the Words of the Men and Women Who Were There, edited by Max Arthur, Lyons Press, Guilford, CT, 2004, 486 pp., illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

The sound archive of the Imperial War Museum in London contains “thousands of recordings of men and women who have served or witnessed the wars and campaigns from the First World War to the present.” Max Arthur and a number of others have culled excerpts from many of these firsthand interviews and transcripts in the museum’s collection.

They have been collected in this collage of personal accounts ranging from civilians in England to soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines of different nationalities who served in theaters around the globe. This book would have benefited from the addition of dates of these retrospective vignettes (to help assess credibility), more contextual and background information, and maps. These interesting and varied participant and eyewitness accounts, arranged chronologically by year, help put a human face on the experience of World War II.

All This Hell: U.S. Nurses Imprisoned by the Japanese, by Evelyn M. Monahan and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee, 1989, reprint, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2003, 264 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $19.95, softcover.

All This Hell: U.S. Nurses Imprisoned by the Japanese, by Evelyn M. Monahan and Rosemary Neidel-Greenlee, 1989, reprint, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2003, 264 pp., illustrations, maps, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $19.95, softcover.

Before World War II, a military assignment to the exotic Philippines was filled with adventure, sports, and excitement. The Japanese attack at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, turned this “Pacific Paradise” into a virtual hell on earth.

Female U.S. military nurses loyally performed their medical duties in the face of the Japanese onslaught on beleaguered Corregidor, Bataan, and in Manila. After the American surrender in May 1942, almost 60 Army and Navy nurses were sent to the Santo Tomas Internment Camp in Manila. With a shortage of medical supplies and food, and suffering tremendous privations, these nurses courageously persevered and treated their fellow internees to the best of their ability.

Finally liberated by American forces in February 1945, they were repatriated to the United States. According to the authors, although apparently unsubstantiated, the returning nurses then “signed statements agreeing not to speak of the atrocities they had seen.” This compelling narrative, told mainly through a female lens, sheds great light on the sacrifices and contributions of these “Angels of Bataan and Corregidor.”

Gallant Lady: A Biography of the USS Archerfish, by Ken Henry and Don Keith, Forge Books, New York, 2004, 352 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Gallant Lady: A Biography of the USS Archerfish, by Ken Henry and Don Keith, Forge Books, New York, 2004, 352 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover.

The USS Archerfish, named after a fish that stuns its prey from below then devours its kill in the water, was a fabled U.S. Navy submarine. Commissioned in 1943, the nearly 312-foot, diesel-powered, Balao-class submarine, SS-311, conducted seven war patrols in the Pacific during World War II. The fifth war patrol was the most successful and spectacular, as the Archerfish sank the 59,000-ton Japanese aircraft carrier Shinano, “the largest ship ever sent to the bottom by a submarine.”

During the 1950s, the Archerfish conducted geological and gravitational surveys in the Atlantic. From 1960 to 1968, the submarine executed lengthy hydrographic surveys. The missions were so long that the Navy recruited an all-bachelor crew for the Archerfish, reportedly the only time this was done in the sea service. The Archerfish did its duty to the end, serving as a floating target and sunk in 1968. This engagingly written book is a captivating biography of the Archerfish, its accomplishments, and its crews.

The First Battalion of the 28th Marines on Iwo Jima: A Day-by-Day History from Personal Accounts and Official Reports, with Complete Muster Rolls, by Robert E. Allen, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 470 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography, index, $45.00, softcover.

The First Battalion of the 28th Marines on Iwo Jima: A Day-by-Day History from Personal Accounts and Official Reports, with Complete Muster Rolls, by Robert E. Allen, McFarland, Jefferson, NC, 2005, 470 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography, index, $45.00, softcover.

The pear-shaped, eight-square mile rocky island of Iwo Jima witnessed some of the fiercest and bloodiest fighting in the Pacific theater during World War II. The capture of Iwo Jima, according to military planners, would permit the U.S. to have a forward air base from which to bomb the Japanese home islands.

Three U.S. Marine divisions assaulted the volcanic island on February 19, 1945, with seven battalions landing on its eastern beaches. One of these seven battalions was the 1st Battalion, 28th Marines. Author Robert E. Allen served in 1st of the 28th Marines on Iwo Jima and has skillfully compiled a day-by-day detailed record of the battalion’s activities. Each chapter presents a daily overview, operational and logistical details, casualties, and copies of unit after-action reports. Appendices include unit muster rolls, award citations, and details on each 1/28th Marine who fought on Iwo Jima. This thoroughly researched and detailed reference book is a fitting tribute to those 1/28th Marines who earned on Iwo Jima two Medals of Honor, six Navy Crosses, numerous Silver Star and Bronze Star medals, and 903 Purple Hearts. The 1/28th Marines proved on Iwo Jima that “uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

The SA Generals and the Rise of Nazism, by Bruce Campbell, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2004, 288 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $22.95, softcover.

The SA Generals and the Rise of Nazism, by Bruce Campbell, University Press of Kentucky, Lexington, 2004, 288 pp., illustrations, notes, bibliography, index, $22.95, softcover.

This is a captivating and thought provoking individual and collective portrait of the top leadership of the paramilitary wing of the Nazi party, the Sturmabteilung (SA, or storm troopers, the brown shirts). Working with an impressive array of archival sources, historian Bruce Campbell examines the careers of the 178 men who held the three highest ranks in the SA hierarchy (in descending order, Stabschef, Obergruppenfuhrer, and Gruppenfuhrer). These men were the leaders, decision makers, and administrators of the SA who set the tone for its operations. Campbell clearly understands the important role of the SA in enabling the Nazis to gain power and thereafter to intimidate and marginalize opposition.

The activities of the SA, according to Campbell, “were all critical in transforming the Nazi party from a small band of fanatics into the largest mass political party in the history of Germany up to that time.” The SA was so successful in helping Hitler and the Nazis seize and consolidate power that it rivaled the Fuhrer, resulting in the “Rohm Purge” of 1934. This eliminated much of the SA’s senior leadership, reduced its significance, and arrested its development. Campbell’s intriguing study of the SA leadership helps one understand the attraction, organization, and machinations of the Nazi Party.

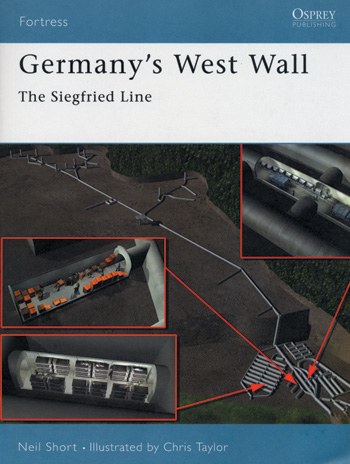

Germany’s West Wall: The Siegfried Line, by Neil Short, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, 64 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, tables, sources and bibliography, glossary, index, $16.95, softcover.

Germany’s West Wall: The Siegfried Line, by Neil Short, Osprey Publishing, Oxford, UK, 2004, 64 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, tables, sources and bibliography, glossary, index, $16.95, softcover.

Germany reoccupied the demilitarized Rhineland in early 1936. The construction of the West Wall, or Siegfried Line—the topic of this superb study—began shortly afterwards. The purpose of the West Wall was to “deter France from invading Germany in support of her allies [Poland and Czechoslovakia] or, if France did attack, enable much weaker forces to slow the advance while the campaign in the east was brought to a swift conclusion.”

Most of the West Wall was completed in 1940, when it stretched about 300 miles from Cleve in the north to the Swiss border. This book, a volume in the Osprey Fortress series, describes in detail the design, development, and construction of the West Wall. Subsequent chapters cover the principles of defense and site selection, workers’ and soldiers’ accommodations and fighting positions, the West Wall’s wartime operational history, and its fate in the wake of the Allied onslaught in late 1944 and 1945. This informative monograph contains numerous photographs, full color and cutaway artwork, and other illustrations of the famous cement “dragon’s teeth” and “hedgehog” anti-tank defenses of the vaunted Siegfried Line.

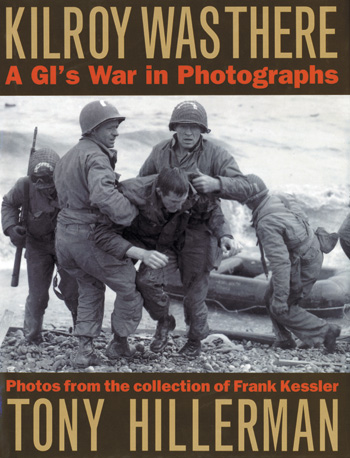

Kilroy was There: A GI’s War in Photographs, by Tony Hillerman, Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2004, 79 pp., illustrations, $25.00, large format hardcover.

Kilroy was There: A GI’s War in Photographs, by Tony Hillerman, Kent State University Press, Kent, OH, 2004, 79 pp., illustrations, $25.00, large format hardcover.

“Kilroy” was the ubiquitous bulb-nosed caricature of an American soldier seen peering over a fence in graffiti that accompanied U.S. forces during World War II. It was the trademark, even the signature, of the average soldier. Frank Kessler served as a Signal Corps photographer, capturing frank images of soldiers—Kilroys—at war from the Normandy beaches to the streets of Berlin. Kessler’s photographs were taken not to glorify or justify the conflict or serve as propaganda for a stateside audience. They show, among many others, soldiers in action in the hedgerows, men patrolling through the rubble of French villages, medics treating wounded American and German soldiers, and Sherman tanks lined up to serve as artillery.

A rare sequence of photographs shows German soldiers being executed by an American firing squad after the Battle of the Bulge. Many snapshots, saved by Kessler at the end of the war, transform seemingly mundane events into significant images. With an accompanying narrative by prolific author and decorated World War II infantryman Tony Hillerman, this superb books makes a worthy contribution to the photographic record of U.S. Army participation in the war in Europe.

On Hitler’s Mountain: Overcoming the Legacy of a Nazi Childhood, by Irmgard A. Hunt, William Morrow, New York, 2005, 288 pp., illustrations, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Irmgard A. Hunt (nee Paul) was born in Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, in 1934, one year after Adolf Hitler assumed power in Germany. Hitler chose Obersalzberg, a hamlet in the mountains above Berchtesgaden, as his home and headquarters. As a result, according to Hunt, Hitler’s “presence on that mountain stamped my early years with a uniqueness that could not be claimed by other middle-class children in Germany.”

Based upon family records and lore, diaries and letters, and her own memories and perceptions, Hunt stresses the trials and tribulations of everyday life for the average German family. She begins by chronicling the lives of her grandparents, from the World War I generation, and then of her parents. The standards of the German family reflected those of the German state: “unquestioning obedience, submission, orderliness, and hard work.” The continued financial hardships, high unemployment, and political turmoil of the post-World War I years paved the way for the advent of Hitler. Hunt, the model of the blue-eyed, blonde-haired Aryan, even sat on Hitler’s lap in 1937. She chronicles the family reaction during the drift to war, the pervasive anti-Semitic attitudes, her draftee father’s death in action in France in 1941, and increasing hardship and disillusion.

While Hunt’s intriguing and provocative retrospective is an attempt to exorcise old Nazi ghosts, it is also a cautionary tale. According to Hunt, one should always be on the lookout for the signs “of dictatorships in the making and to resist politics that are exclusive, intolerant, or based on ideological zealotry, and that demand unquestioned faith in one leader and a flag.”

The Devil’s Brigade, by Robert H. Adleman and George Walton, 1966, reprint, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 261 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $18.95, softcover.

The Devil’s Brigade, by Robert H. Adleman and George Walton, 1966, reprint, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 261 pp., illustrations, maps, index, $18.95, softcover.

The 1st Special Service Force, unique in consisting of American and Canadian soldiers, was formed in 1942. Originally conceived to sabotage oil facilities in Norway and Romania, the Force is best remembered for its superb service in the “meat grinder” of the Italian campaign. It led attacks in Italy that opened the way for the Allied advance to Cassino. Later, the Force participated in the breakout from the Anzio beachhead and the Allied drive on Rome before being disbanded in late 1944.

The Germans called the Force soldiers the “Black Devils” because of their frequent stealthy night operations while wearing dark face camouflage. In fact, one German soldier was heard muttering, “Schwartzer Teufel,” (black devil) just before his throat was slit by a Force soldier. This fast-paced narrative, containing much anecdotal material, is a fitting tribute to and helps preserve the fighting spirit of the indomitable Black Devils of the 1st Special Service Force, the forerunner of today’s Green Berets.

The German Fleet at War, 1939-1945, by Vincent P. O’Hara, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 344 pp., illustrations, maps, tables, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The German Fleet at War, 1939-1945, by Vincent P. O’Hara, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2004, 344 pp., illustrations, maps, tables, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The German Navy is well known for having conducted sustained and generally effective submarine warfare during World War II. German warships also fought in a number of prominent surface engagements, notably Bismarck’s sinking of HMS Hood (May 24, 1941) and the pursuit and sinking of the former three days later. Naval enthusiast Vincent P. O’Hara shows in this seminal study that the German Navy’s role in World War II was much more significant and complex than many appreciate.

He chronicles in detail 69 surface engagements the German Navy fought against British, French, American, Polish, Soviet, Norwegian, and Greek warships. These case studies begin with the German Navy’s attack on Polish ships near Hel on September 3, 1939, and conclude with convoy attacks in Scandinavian waters in late 1944 and early 1945. O’Hara provides detailed narratives of the tactical situation, ably placing them within their operational and strategic contexts, for each surface action. The text is supplemented by excellent, easy-to-understand tables that list participating ships by nationality and include the size, speed, armament, and damage (if any) of each ship involved.

There are many superb maps, and appendices contain additional information and statistical analyses of the relevant naval battles. This outstanding book is an invaluable resource for all students of World War II naval history.

Our Last Mission: A World War II Prisoner in Germany, by Dawn Trimble Bunyak, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2003, 259 pp., illustrations, map, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Our Last Mission: A World War II Prisoner in Germany, by Dawn Trimble Bunyak, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2003, 259 pp., illustrations, map, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover.

Technical Sergeant Lawrence I. Pifer, U.S. Army Air Corps, was one of an estimated 94,000 prisoners of war (POWs) held in Europe in World War II. As ball turret gunner and radio operator on the B-17 bomber Slightly Dangerous, Pifer parachuted from the plane damaged during a raid over Germany on March 4, 1944. He was captured by the Germans and embarked on a 14-month ordeal of “torture, starvation, disease, and forced marches.” This worthwhile account, based upon numerous interviews Pifer gave to his niece more than five decades after World War II, highlights the daily routine, trials, and tribulations while in captivity. Instead of concluding with the end of the war and Pifer’s repatriation, this book chronicles his difficulties adjusting to civilian life. Our Last Mission is a poignant and realistic POW narrative “of an average enlisted man’s struggle to survive in the face of hopelessness, with only his strong faith and pride in country to sustain him.”

The Battle for Rome: The Germans, the Allies, the Partisans, and the Pope, September 1943-June 1944, by Robert Katz, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2003, 396 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, appendices, sources and notes, bibliography, index, $28.00, hardcover.

The significant battle for Rome, which was captured by the Allies on June 4, 1944, has been overshadowed not only by the Normandy landings that took place two days latter, but also by other factors. This superb study, written by prominent historian Robert Katz, is much more than a campaign chronicle or battle analysis and sets the historical record straight. He has focused on the 270-day German occupation of Rome, from September 8, 1943, when Italy capitulated, until the Allies captured the Eternal City.

An important episode in this occupation was “the boldest and largest Resistance assault, unequaled by the partisan movements in any other of the German-occupied European capitals” on March 23, 1944, when 33 German SS police were killed. Hitler was furious and demanded revenge. In retaliation, the Germans executed 335 Roman men and teenage boys the following day in the Ardeatine Caves. These and many other tangled events, activities, and behind-the-scenes negotiations, involving the Germans, Pope Pius XII and other Vatican officials, various Italian partisan factions, the Allies, and Romans, figure prominently in this compelling volume. Impeccably researched and engagingly written, The Battle for Rome is an indispensable and detailed reference for anyone interested in the Italian campaign and the role of the Vatican.

Victory Road, by Robert C. Baldridge, 1st Books, Bloomington, IN, 2003, 163 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography, $18.95, large format softcover.

Victory Road, by Robert C. Baldridge, 1st Books, Bloomington, IN, 2003, 163 pp., chronology, illustrations, maps, appendices, bibliography, $18.95, large format softcover.

Victory Road is the retrospective World War II personal account of Robert C. Baldridge, a bright and determined field artilleryman who served in combat from Normandy to the Elbe River and V-E Day. Baldridge, the son of a congressman from Nebraska, entered Yale in 1942. Eager to not miss the war, he joined the Enlisted Reserve Corps and entered active duty as an artillery private the following year. After deploying to England as an individual replacement, he was assigned to the 34th Field Artillery, a 155mm howitzer battalion (commanded by Lieutenant Colonel, later General, William C. Westmoreland) of the 9th Infantry Division.

Baldridge landed at Normandy on D + 4, fought through northern France, Belgium, the Huertgen Forest (“an exercise in futility and death that should never have happened”), the Bulge, the Siegfried Line, and across the Roer and Rhine Rivers. Baldridge received a battlefield commission shortly before the end of the war, and his “victory road” ended in the German heartland. This detailed, reflective account is an interesting addition to the literature of World War II soldiering and ground combat.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments