By Eric Niderost

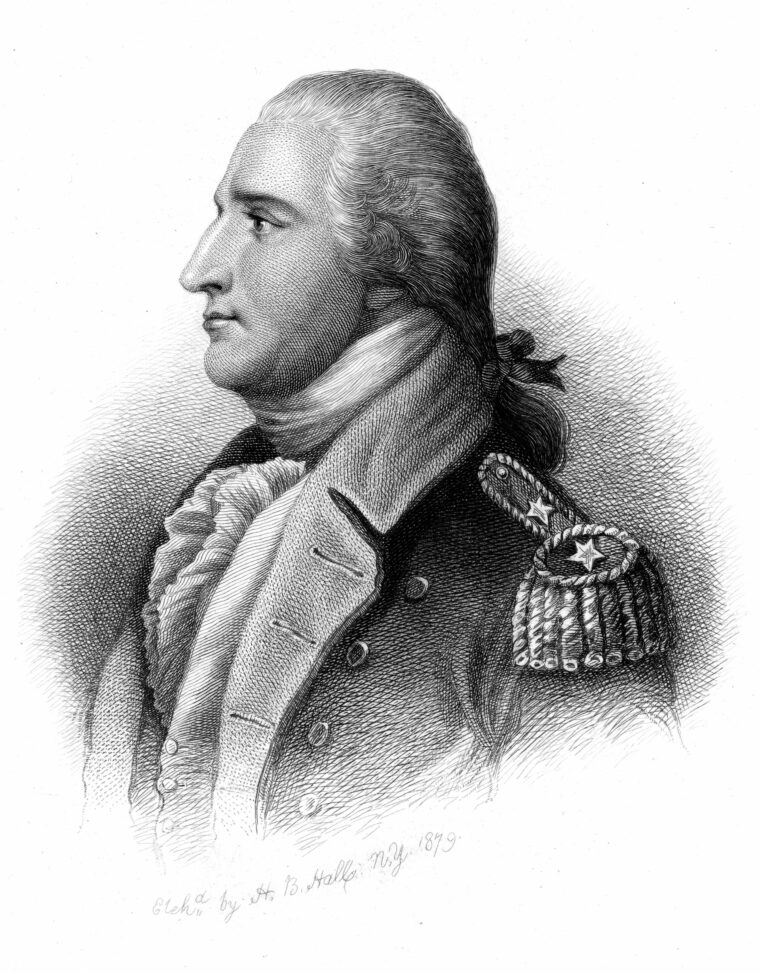

On the morning of October 11, 1776, Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold restlessly paced the deck of his flagship Congress. The American colonists had declared their independence from Great Britain just three months before, and already the revolution was in serious trouble. An American invasion of Canada had been aborted, and commanding general George Washington had his hands full battling a large British army in New York.

Even worse threats loomed on the horizon. A large British fleet was preparing to sail down Lake Champlain, the vanguard of a full-scale invasion designed to cut off New England from the rest of the fledgling United States. Arnold was waiting for word that the British were finally on the move. Sometime between seven and eight o’clock in the morning, the schooner Revenge, dispatched earlier to scout enemy movements, reported back with solid if troubling intelligence that the British were sailing down the lake in full force.

Arnold greeted the news with a mixture of alarm and anticipation. Now at last was a chance for action, an opportunity to win fresh laurels for himself and his country. But Arnold’s growing enthusiasm was checked by the arrival of Brig. Gen. David Waterbury, Arnold’s second in command, an experienced mariner whose opinions carried some weight. Arnold greeted him, and the two began an impromptu council of war. Waterbury carefully took stock of his new commander. Arnold was short, perhaps 5 feet, 6 inches tall, with a barrel chest and muscular limbs that gave an impression of pint-sized pugnacity. His features were sharp, almost hawklike, with a Roman nose projecting out like a raptor’s beak. His blue-and-buff uniform was neat, and he did not seem to favor his left leg, which had been wounded in Canada a few months before.

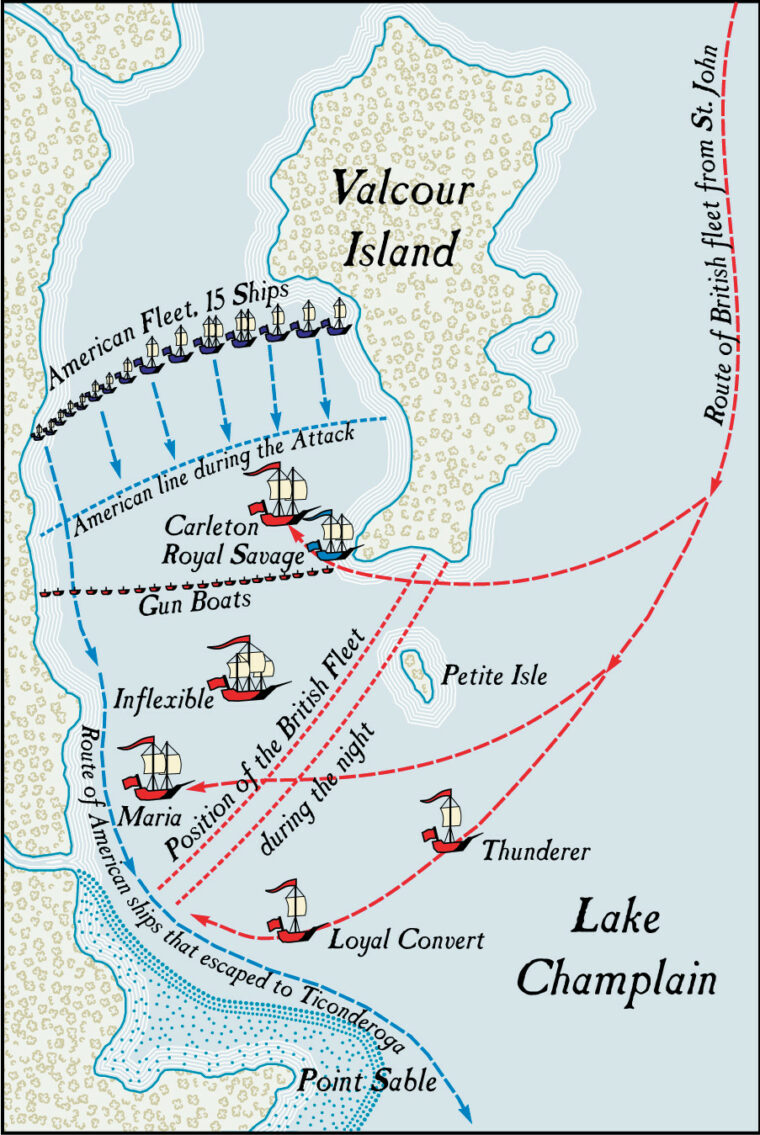

Reports showed that the Americans were badly outnumbered. The ragtag rebel fleet, 15 vessels in all, was sheltering in a channel near Valcour Island. Valcour’s wooded bulk provided some much-needed cover, allowing the American vessels to pounce on the enemy without warning. But Waterbury felt that the inlet was a potential trap, and that once the British located the Americans, the colonials would be easily overwhelmed and destroyed. “General Arnold,” he said, “I urge you to come to sail and fight them on a retreat in the main lake.” If they stayed where they were, Waterbury cautioned, “The enemy would be able to surround us on every side since they lay between the island and the New York shore.” Waterbury was no coward, and Arnold listened respectfully before dismissing his ideas. He had had his fill of retreating—the memory of the Canadian fiasco still rankled. No, the British must be stopped, or at least delayed until “General Winter” became an American ally.

Like many of his men, Arnold was still smarting from the Canadian misadventure. An American invasion of Canada had seemed an attractive prospect, at least on paper. The looming threat of a British thrust from the north would be checkmated, and the rebels might find allies in a French-Canadian population that resented British rule. Arnold had been a prime sponsor of the invasion, and he soon won the approval of Washington. The ensuing campaign was an epic of courage and endurance against impossible odds. Hundreds of miles of almost impenetrable wilderness lay between the Americans and their goal. Arnold’s colleague, General Richard Montgomery, managed to take Montreal after an epic march, but Quebec proved a tougher nut to crack. Arnold and his men also endured incredible hardships, conditions rivaling Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow in 1812, before putting Quebec under siege.

On December 31, 1775, the Americans attacked Quebec in the teeth of a blinding winter storm. The assault was heroic but abortive. Arnold was badly wounded in the left leg, and Montgomery killed by a blast of grapeshot. With their leaders out of commission, the Americans fell back, although they continued a half-hearted siege. Once the ice that choked the St. Lawrence River broke up, the British were able to rush reinforcements to Quebec. The Americans were eventually forced to raise the siege and retreat. They had come within an ace of success, but all their efforts had ended in heroic failure. The military initiative passed to the British.

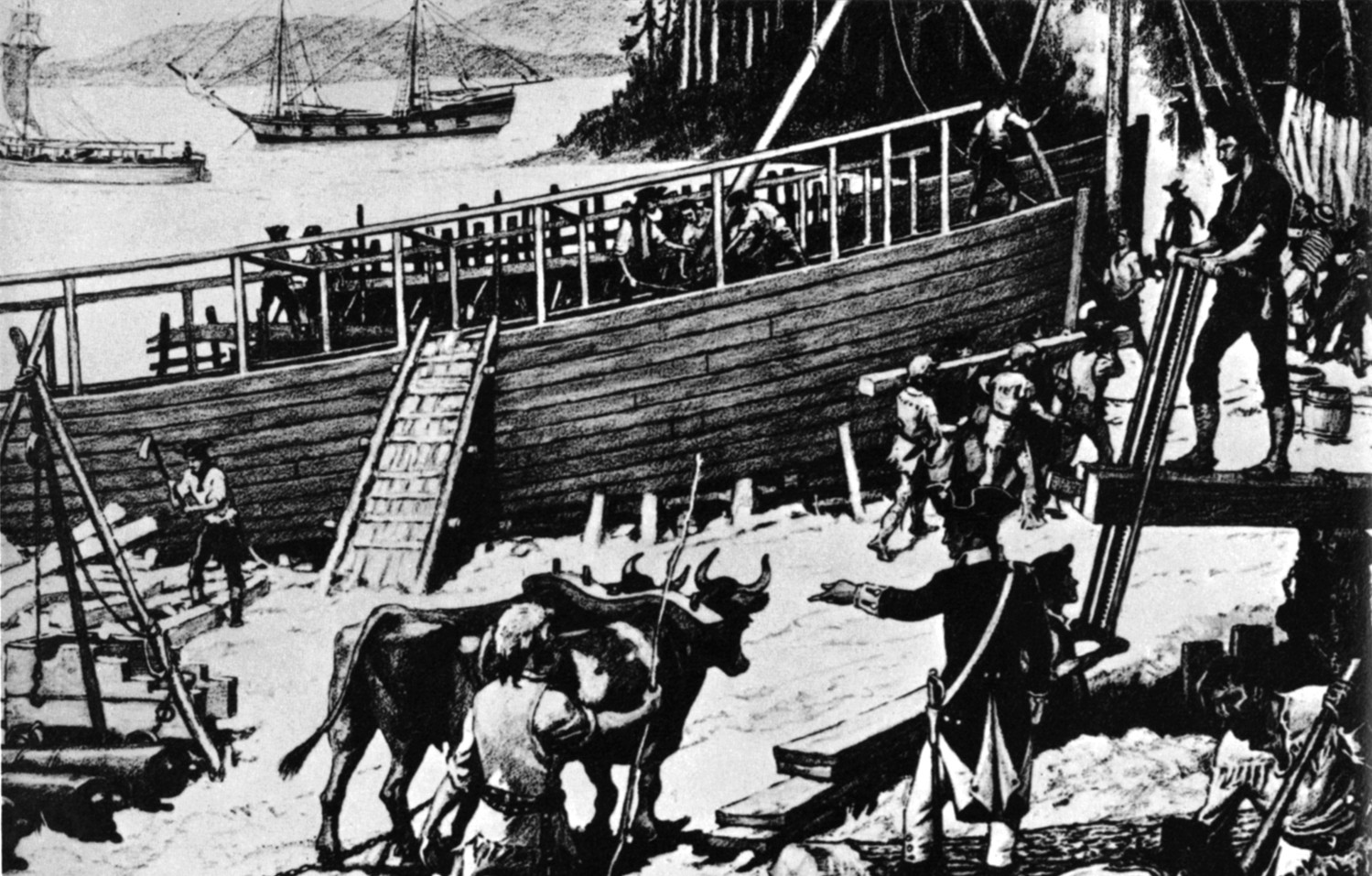

Congress was still in session in Philadelphia, grappling with the critical issues of war and independence. The representatives were deeply divided, and many continued to think in regional, not national, terms. Luckily, the Marine Committee of Congress recognized the danger of a British counter-thrust from Canada. The committee ordered General Philip Schuyler of New York to build, “with all expedition, as many galleys and armed vessels as shall be sufficient to make us indisputably masters of the lakes Champlain and George.” Schuyler, well aware of the threat, already had ordered carpenters to assemble at Skenesborough, N.Y., to begin work on an American fleet. The rebels had a token force on Lake Champlain—the schooners Liberty, Royal Savage, and Revenge, and the sloop Enterprise. These would form the nucleus of a fleet that would bar any attempted British invasion.

Skenesborough was an excellent choice for an American shipyard. It was located at the head of Lake Champlain, just south of Fort Ticonderoga, near a creek that emptied into South Bay. Philip Skene—ironically, a Tory—had established a settlement there in 1765. By 1776 there was an imposing house, corrals, and barns for storing crops. More importantly, there were also two large sawmills and a forge capable of producing the best iron bars in the colonies. It was the perfect location for the Americans to concentrate their efforts in building a fleet. There was no time to waste, so the emphasis was placed on building “gondolas,” flat-bottomed, shallow-draft gunboats that could be built and outfitted relatively quickly. Such vessels would be propelled by oars and, when feasible, given an assist by auxiliary sails.

Work continued through the summer at a furious pace, with axmen, carpenters and blacksmiths working seven days a week in the wilting heat. Woodsmen swarmed though nearby shores harvesting large quantities of white oak, spruce and pine trees. The forests rang with a staccato chorus of dull thuds as axes bit deeply into old-growth trunks. The felled trees were then dragged to waiting sawmills, where water-powered sash saws quickly cut them into suitable planks for the hulls and other parts of the new gondolas. Then the planks were fashioned by traditional means, using broad axes and adzes to shape the wood.

On June 26, 1776, the first gondola, New Haven, was completed at Skenesborough and slid into the placid waters of South Bay. Once the gunboat was launched, she was sent north to Fort Ticonderoga for masting, rigging, and arming. Supply shortages initially crippled the American effort. Captain Richard Varick scoured New York and Connecticut for sailcloth, cordage, anchors, cables, and powder for the fledgling fleet. A steady stream of letters poured forth from Varick’s quill pen, urging sloop owners and merchants at Albany and elsewhere to contribute cordage and blacksmithing tools. The response was gratifying, and soon heavily laden bateaux traveled up the Hudson River to Skenesborough, where wagons were waiting to haul the precious cargos on the last leg of the journey to the shipyards.

General Horatio Gates asked Arnold to go to Skenesborough to personally oversee the. shipbuilding operation. It was a wise choice; Arnold’s enthusiasm and restless energy would add a much-needed shot of adrenaline to the project. Arnold arrived three days before the scheduled launch of the fifth gondola. Philadelphia was a standard size, 57 feet long and 17 feet at the beam. Arnold originally wanted at least some heavy 24-pounder cannons for his fleet, but these proved unattainable. Philadelphia had two 90-pounders amidships and a 12-pounder bow gun. She also carried as many as eight small swivel guns. Arnold delayed Philadelphia’s launching until a mortar platform could be installed on the vessel. The mortar platform was an experiment that went awry. When a mortar shell was fired from a gondola, the shell somehow rebounded and fell back on deck, where it exploded with a thundering roar. No one was killed, which an observer felt was “a great wonder,” but after the mishap Philadelphia and the other vessels were more conventionally armed.

In the meantime, the British were far from idle. Sir Guy Carleton, the royal governor-general of Canada, was uncomfortably aware of just how close the Americans had come to seizing the province. Although they had been repulsed, Carleton was not about to rest on his laurels. In fact, the British government had instructed him to mount an invasion as soon as possible, a southward thrust designed to sever rebellious New England from the rest of the fractious colonies. Since operations would grind to a halt during the winter, speed was of the essence. If Carleton could take Fort Ticonderoga, sometimes called the “key to the continent,” by fall, the British would be in a good position for the 1777 campaigning season.

From the British point of view, it was a heady prospect. A large British army was already well established in the area around New York City. Once Carleton was in Ticonderoga, he could continue his march south through the Hudson River Valley with little fear of interference from the rebel Americans. After Carleton had succeeded in joining forces with General Sir William Howe, New England would be isolated and cut off from outside aid. It was a strategy of divide-and-conquer, and in the summer of 1776 the British looked to the future with hope and anticipation.

The British seemed to have all the advantages on their side. They had the men, materiel, and above all the military expertise to mount an inland-water campaign. Work on a fleet began at once, but there was a logistical problem to be considered before the first tree was felled. How best could the British get to Lake Champlain? From Montreal they could sail down the St. Lawrence River, then enter the Richelieu River and continue southward. But the Richelieu was only navigable as far as Chambly. Between Chambly and Lake Champlain, there was 12 miles of treacherous currents, shallow water and rapids. Carleton decided to partly disassemble the warships and haul them overland by means of a road his troops would hack through the wilderness. The fleet would be augmented by newly built ships constructed at the shipyards of St. Jean. The first to be disassembled and rolled through the portage was the Maria, a schooner destined to be Sir Guy’s flagship. The schooner Carleton and the gondola Loyal Convert soon followed.

Carleton’s growing fleet was the vanguard of the British effort, designed to sweep away any American naval opposition. Once the lake was secured, it would be safe for the British army to proceed. Some 400 bateaux—transport boats designed to carry 30 or 40 men each—were also being built at St. Jean under the supervision of Lieutenant William Twiss of the Royal Engineers. Meanwhile, 7,000 British troops camped around the Richelieu River, an invasion force that included British regulars and German mercenaries. Native American warriors were also on hand, British allies who had little love for the land-hungry Americans.

By the fall of 1776, the British fleet was complete and ready to assume the offensive. The British armada would include five ships, 20 gunboats, and 28 longboats. The very existence of an American fleet, however hastily built and ramshackle, had upset the British campaign timetable. Precious good-weather months were wasted while Carleton laboriously built and assembled a naval force large enough to take on the Americans. By September and early October, the British were at a crossroads. Should they attempt a full- scale invasion so late in the season? It was a question that also occupied the fertile mind of Benedict Arnold.

On August 7, 1776, Arnold finally received sailing orders from Gates. The Declaration of Independence had been signed a month earlier; now the 13 disparate colonies were the United States. Gates proudly used the new title in his dispatch, commanding Arnold to go to Crown Point and then “proceed with the Fleet of the United States under your Command, down Lake Champlain.” Gates made it clear that Arnold was to conduct a defensive action, and that he was not to take any wanton risks with his precious command. If attacked, he was to act with “cool determined valor.” The British must be blocked if they came. Otherwise, Arnold was to keep his nose out of trouble.

Arnold took Gates’ instructions with a grain of salt. Proud as well as pugnacious, he wasn’t going to let his hands be tied by some overly timid superior. Instead, Arnold intended to take the offensive as soon as he was able. He was eager for a fight, but his basic strategic instincts were levelheaded and sound. He wouldn’t rashly blunder into a battle. Instead, he would probe the enemy, scout his positions, and try and sound out the Redcoats’ intentions before committing his navy to a decisive course of action.

Arnold set sail on August 24 with a flotilla of 10 vessels. Included in his fleet were the gondolas Spitfire, Philadelphia, Boston, Connecticut, Providence, and New Haven; the schooners Royal Savage, Liberty, and Revenge, and the sloop Enterprise. The next day, the tiny armada was cruelly buffeted by a raging storm. The howling gales lasted two days and damaged some of the boats, but it was nothing that couldn’t be repaired.

For the next six weeks, Arnold played a dangerous cat-and-mouse game with the British on Lake Champlain. American scout boats probed north, seeking information on enemy strength and positions. Aboard Philadelphia and the other gondolas, living conditions were Spartan, even primitive. Awnings provided some shelter from the broiling sun, but did little to prevent the constant lake winds from chilling men to the bone. Small brick hearths cooked warm food, and rough wooden benches provided some hard and uncomfortable seating. Philadelphia and the other gondolas were designed to hurl artillery fire against an enemy—everything else, including crew comfort, was secondary to their main purpose. The men were weary from constant rowing, cold, ill-clad, and often hungry. Rations were scanty, and supplemented by occasional foraging ashore. But foraging carried it own risks—hostile Indians lurked in the woods, ready to shoot and scalp unwary sailors. Men grew sick from prolonged exposure to the elements, and at one point Arnold sent 23 of the sickest sailors back to Ticonderoga because they were too ill to continue.

Arnold and his ragtag fleet slowly made their way north by stages. At one point, he ordered the men ashore to collect fascines, bundles of saplings that when staked to gondola gunwales formed a fort-like wooden “palisade” around the vessels’ most vulnerable parts. The shoreline was filled with spruce saplings ideal for the purpose. Cut into four-foot lengths and bound together, they provided good cover against enemy fire. When an 18-man party from the gondola Boston went ashore to gather fascines, it was attacked by Native Americans under British command. Two Americans were killed and five others were wounded; the rest managed to make a fighting retreat. Once the shore party had reached safety, the American fleet raked the woods with fire, but the shadowy enemy was already gone.

By late September, the fleet had been on Lake Champlain for over a month, with no end in sight. Discipline—never great among the New Englander militia that made up much of Arnold’s command—began to erode. When battle seemed imminent, four men defiantly refused to fight. Before the war, Arnold had occasionally captained his own ships in trading ventures to the West Indies and Europe. He knew the corrosive dangers of a mutiny at sea, and his reaction was swift and harsh—he sentenced the offenders to a whipping at each vessel in the entire flotilla. In doing so, Arnold was taking a leaf from his British enemies. The punishment was an old Royal Navy custom called “flogging ‘round the fleet.” In the giant British navy, such a punishment tour could mean hundreds of lashes and the ultimate death of the victim. In this case, the mutinous American sailors received “only” 78 strokes each.

On September 24, the Continental fleet finally reached Valcour Island, a heavily wooded outcropping two miles long and one mile wide. Arnold’s galleys, gondolas and other ships anchored in a channel between the island and the New York shore. It was an ideal defensive position against a superior enemy. Arnold realized that his ships were poor sailing vessels, heavy and sluggish. In contrary winds they were almost impossible to maneuver, even with every man putting his back into the sweeps. To make matters worse, few of his command were true sailors; as he ruefully noted, “we have but very indifferent men.” On another occasion, he described his men as “a motley, miserable set…the refuse of every regiment.” Arnold knew, as well, that his men were up against veteran officers of the Royal Navy, men who were professionals to the core. Even common British seamen, the oft-abused “Jack Tars,” were seasoned sailors who could handle anything afloat.

Valcour Island’s looming bulk hid the American fleet from any enemy vessels that might be approaching from the north. The British had all the maritime advantages, and they knew it. Perhaps they would become overconfident and make a mistake that Arnold could exploit. He hoped to stay in the channel, laying in wait for the unwary British fleet. If the British did not detect Arnold’s hiding place, they might sail past Valcour Island and be caught in a strung-out, vulnerable position. The Americans might be able to pounce on a ship or two before other British vessels could come to their aid.

In the main, however, Arnold intended to fight in the channel between the island and the New York shore. Most of his ships would be in a half-moon position, a defensive crescent that could deliver a concentrated blast of fire. Consciously or unconsciously, Arnold was adopting the tactic used by the ancient Greeks in 480 bc. Outnumbered by a huge Persian fleet, the Greeks had formed a defensive arc at Salamis Bay. Unable to come to grips with the enemy or use their superior number to advantage, the Persians were heavily defeated. Eighteenth century gunpowder and solid shot were quite different from Greek spears and arrows. Nevertheless, the tactical principles were much the same. All Arnold’s cunning would come to naught if the British detected him before he could attack. Arnold now had 15 vessels in his tiny fleet—two schooners, three galleys, a sloop, a cutter, and eight gondolas. (The schooner Liberty had been sent back for supplies). Among the new ships joining the armada were the two-masted galleys Washington, Trumbull, and Congress, and the cutter Lee.

On October 4, the British set sail in search of the Continental fleet. Four of Carleton’s largest and most powerful ships led the way in the vanguard. Captain Thomas Pringle was in tactical command, but Carleton decided to accompany the Royal Navy officer aboard his flagship, the schooner Maria. Inflexible was also present, a ship-rigged, three-masted warship boasting an array of 12-pounder cannons. The gun ketch Thunderer and the gondola Loyal Convert rounded out the British quartet.

A large cluster of 24 gunboats, four longboats, and a few supply craft followed in the wake of the vanguard like ducklings trailing their mother. A swarm of bateaux and canoes brought up the rear. The bateaux were filled with Redcoats ready to act as marines should the need arise, while the canoes were loaded with 650 Indian warriors. The trees were already starting to turn color, painting the hills with a blaze of russet and orange. Some of the high peaks already had patches of snow. The campaigning season was rapidly drawing to a close.

The British armada made good progress down Lake Champlain, their vessels aided by a strong wind blowing from north to south. The British vanguard sailed past Valcour Island and Arnold’s anchorage, blissfully unaware of the Americans’ presence. About 10 am, British surgeon Robert Knox, who was accompanying Carleton and Pringle aboard Maria, looked back and caught a glimpse of one of the Continental ships. Pringle was quickly alerted and started to issue a flurry of orders, but by this time the British were about two miles past of Valcour Island’s southern tip. This meant that the Americans had the weather gauge—the prevailing north-northwestward wind was in their favor. Pringle ordered his fleet to turn about and engage, but this was literally easier said than done against a strong wind, even when aided by sweeps.

Sailing against the wind meant tacking, carving out a slow and laborious zig-zag path to the enemy. Maria was having difficulty performing these intricate maneuvers, giving Pringle an excuse to anchor the schooner well out of harm’s way. It was a controversial decision, and later led to suggestions of cowardice on Pringle’s part.

In the meantime, the Americans were far from idle. Arnold ordered his fleet to come to anchor in line of battle, forming a half-moon defensive position. Royal Savage, the largest vessel in Arnold’s command, attempted to comply, but in the process ran aground on Valcour Island. This was a serious blow to the Americans—their most powerful vessel was almost immediately out of action and helpless. British gunboats swiftly closed for action. Propelled by oar-like sweeps, they were less dependent on the whims of the weather. Scenting blood, the British converged on the helpless Royal Savage like a wolf pack on a wounded deer. Frustrated in their efforts to refloat Royal Savage and taking heavy British fire, the crew had no choice but to abandon ship and swim for the island. A boarding party led by Lieutenant Edward Longcroft swarmed over the gunwales and seized the battered vessel as a prize.

The Redcoats managed to scour the island and capture 20 members of Royal Savage’s crew, but their triumph was short-lived. Arnold’s fleet—at least those who were able to bring their guns to bear—trained their cannons on the grounded ship and began to bombard their former colleague. Cannonballs flew so thickly that half the landing party was killed and wounded. Unsupported, Longcroft reluctantly abandon his prize.

By 11 am, the engagement had become general. The British gunboats closed on the American battle line, their cannons belching smoke and fire, and the American artillery flamed in counter-battery. Arnold, aboard Congress, was in the thick of the fight as usual, acting as gun captain on occasion for several of the vessel’s 18- and 12-pounders. British shot smashed through Congress’ hull, disemboweling and severing limbs with horrifying ease. Those not directly in the path of the hurtling missiles were wounded by the showers of wooden splinters thrown up in their wake.

Ear-splitting cannon reports mixed with the moans and cries of the wounded and the shouts and oaths of sweating, powder-grimed men. Blood flowed, staining the oak decks of the Congress a dark crimson, but Arnold stood firm, coolly aiming and firing cannons as if oblivious to the carnage all around him. Congress was taking terrific punishment, as was Washington, but their hard-pressed crews made sure their own fire never slackened.

In fact, the American amateurs, maligned at times by Arnold himself, were giving a very good account of themselves. In one instance, an American cannonball sliced through a British gunboat with uncanny accuracy, killing one gunner and tearing off the leg of a seaman before embedding itself into a bulwark. Another lucky American shot smashed into the powder magazine with predicable results. The powder ignited, sending up a great mushroom of smoke and flame, injuring the crew.

A number of German mercenaries were serving with the British that day. One of them, Captain George Pausch of the Hesse-Hanau Artillery, left an account of the incident. Pausch commanded his own gunboat, and his sergeant pointed out where the explosion had taken place. It was obvious that the stricken gunboat needed help, since she was engulfed in flames. Pausch did what he could to pick up survivors, many of whom had dived into the lake, but soon his own vessel was so overloaded that she threatened to founder. Eventually a third gunboat took off some of the excess men.

Thus far, the British gunboats had taken the brunt of the fighting, but now, somewhat belatedly, one of the larger British ships went into action. Carleton, commanded by Lieutenant James Dacres, came up and anchored just opposite the American crescent, 350 yards from the rebel position. Carleton’s gun crews worked with a will, and nearby British gunboats also lent a hand when they could.

It was now past one o’clock, and the battle was at its height. At close quarters, combatants freely used grapeshot—bags of grapefruit-sized iron balls that sent out lethal shotgun sprays of deadly metal. Jaheil Stewart, an American serving aboard the fleet hospital ship, was in a good position to observe the action. “The battel,” he wrote with typically colorful frontier spelling, “was verrey hot (and) the Cannon balls and grape Shot flew verrey thick.”

The Americans accepted Carleton’s proffered gauntlet and began concentrating their fire on the British schooner. Carleton’s cable spring, which held her to the wind, was shot away, and as the long minutes passed, the ship swung helplessly at anchor until her bow faced the enemy line. This exposed her to raking fire, a ship captain’s worst nightmare. Enemy cannonballs could now travel the length of the vessel, plowing through the ship from stem to stern. Dacres himself was badly wounded and knocked unconscious by one such shot. Bloodied and sprawled on his quarterdeck, Dacres was assumed to be dead and was nearly thrown overboard by his crew. A quick-thinking young midshipman, Edward Pellew, intervened and saved Dacres’ life. In short order, Carleton’s second-in-command had his arm blown off, leaving the 19-year-old Pellew in command of the ship. Carleton was a gory shambles, riddled so badly by enemy shells that she had two feet of water in her hold.

Pellew climbed out onto Carleton’s bowsprit to try and set the jib sail under a murderous hail of American shot. The attempt was unsuccessful, but the courageous young midshipman finally managed to throw a line to some nearby tow boats, which pulled the larger ship to safety. By this time, half of Carleton’s crew was dead and wounded, transforming the ship into a virtual charnel house. Pellew survived the carnage to become famous four decades later as Admiral and Viscount Exmouth, destroying the entire Algerian fleet in 1816 during England’s war with the Barbary Coast pirates.

With Carleton out of the fray, Thunderer came up to take her place, the mouths of her great 24-pounders expelling great clouds of smoke laced by searing fingers of flame. The accompanying fire did heavy damage to the American ships, the noise filling the channel and helping the British vessel live up to her name. Thunderer’s heavy cannons all but silenced the punier American guns. The gondola New York suffered a merciless pounding that killed or wounded all but one of her officers, while the galley Washington suffered repeated hits to her hull and mainmast. Arnold’s Congress was struck repeatedly, but Arnold himself escaped without a scratch.

Around 5 pm, the 180-ton warship Inflexible finally entered the action, firing five pointblank broadsides into the American line. The fight was quickly going out of Arnold’s men, but the gathering dusk mercifully drew a dark curtain over the scenes of carnage. Wreckage and bodies floated on the lake’s wind-dimpled surface. The British had returned briefly to the grounded Royal Savage, but only long enough to set her ablaze. As night fell, the burning vessel bathed the island and nearby waters in an almost ethereal glow. Finally the fire reached the ship’s magazine, blowing what remained of the ship into the inky void.

The British ships pulled back, but fully intended to renew the engagement the next day. Carleton’s larger ships had not seen much action, but once their heavier guns were brought to bear on the morrow, the American fleet’s fate would be sealed. The half-mile-wide channel had once been a refuge and a hiding place to launch a possible ambush—now it seemed a trap. Arnold summoned a council of war to discuss his options. Royal Savage was a flame-gutted wreck; Congress and Washington were badly damaged and had sustained heavy casualties. The gondola Philadelphia had been hulled several times, and finally sank about an hour after the battle ended, a victim of a well-placed British 24- pound cannonball. The fleet as a whole had been battered, and total losses were 60 dead or wounded.

The British had lost a similar number of dead and wounded. One British gunboat had blown up, and Carleton had been badly damaged. Pausch noted that “the cannon of the rebels were well served; for as I saw afterwards, our ships were pretty well mended and patched up with boards and stoppers.” When all was said and done, however, the British still outnumbered and outgunned their opponents. The Americans had expended three-quarters of their ammunition. There was nothing to do but retreat under the cover of darkness, a risky maneuver since the Americans would have to run past a screen of Royal Navy ships before reaching the comparative safety of the open lake.

The American flotilla began its desperate dash for escape about 7 pm The galley Trumbull led the way, followed by what remained of the battered gondolas. Washington and Congress brought up the rear. Strict silence was maintained, and the retreating ships, spaced 100 yards apart, had only one hooded lantern each in their sterns to maintain contact with their fellows. Somehow, the Americans managed to squeeze through a small gap between the New York shore and the British picket line of ships.

The American fleet limped down to Schuyler’s Island, nine miles south of Valcour Island. It was a time to try to repair battle damage, and perhaps savor their almost miraculous escape. The Americans had been lucky, as even Arnold admitted, but their luck was not likely to hold. Two of the American gondolas were so badly damaged they had to be scuttled, and the cutter Lee was also abandoned.

The British were astounded by the way in which the rebels had escaped from under their very noses. An abashed Carleton awoke the next morning to find the Americans gone. “To our great mortification,” he reported, “we perceived that they had found means to escape us unobserved by any of our guard boats or cruisers. Thus an opportunity of destroying the whole rebel naval force, at one stroke, was lost.” The Americans, he conceded, had used “great diligence in getting away from us.” Cheated of their prey, the British started to pursue the fugitive fleet with a vengeance.

The next phase of the unequal contest evolved into a running battle. Leaving Schuyler’s Island, the remaining American ships fought a stiff headwind as they headed for the comparative safety of Crown Point. One by one, however, they were overtaken and seized by the swifter British vessels or else were scuttled by their own men to avoid capture. Aboard the half-crippled Washington, General Woodbury was forced to strike his colors, and he and 110 men surrendered to the enemy. Arnold’s Congress and four surviving gondolas managed to stay just ahead of the enemy, although the British came close enough to hit Congress repeatedly with cannonballs and grapeshot. “They kept up an incessant fire on us for about five glasses [two and a half hours],” Arnold reported. “The sails and rigging of the Congress were shattered and torn to pieces, the first lieutenant and three men killed.”

Arnold managed to shepherd his bettered survivors into Ferris Bay, 10 miles north of Crown Point. The American commander may have been headstrong at times, but he was also a realist. He ordered the five remaining vessels, his flagship included, put to the torch. As a gesture of defiance, Arnold insisted that the flags on Congress remain flying, continuing to wave proudly until tongues of flame finally consumed.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments