By Eric Niderost

Colonel Axel Gyllenkrok had had a lot on his mind in recent weeks. It was the autumn of 1708, and as the Swedish Army’s general quartermaster he was not only responsible for supplying its needs on campaign, but he also functioned as an operational manager. In the latter role he poured over maps and traced out what he thought were the best routes to travel to achieve the king’s goals. Once a route had been determined, he would present his findings to commanding general King Charles XII for final approval.

Gyllenkrok was with the main Swedish Army at Tartarsk, which at the time was on the border with Russia. For the last few months King Charles had been playing a kind of cat-and-mouse game with Russian forces under the command of Czar Peter I, later known as “Peter the Great.” Charles’ objective was nothing less than the total defeat of the czar and the irrevocable destruction of Russia’s growing power and influence in Europe.

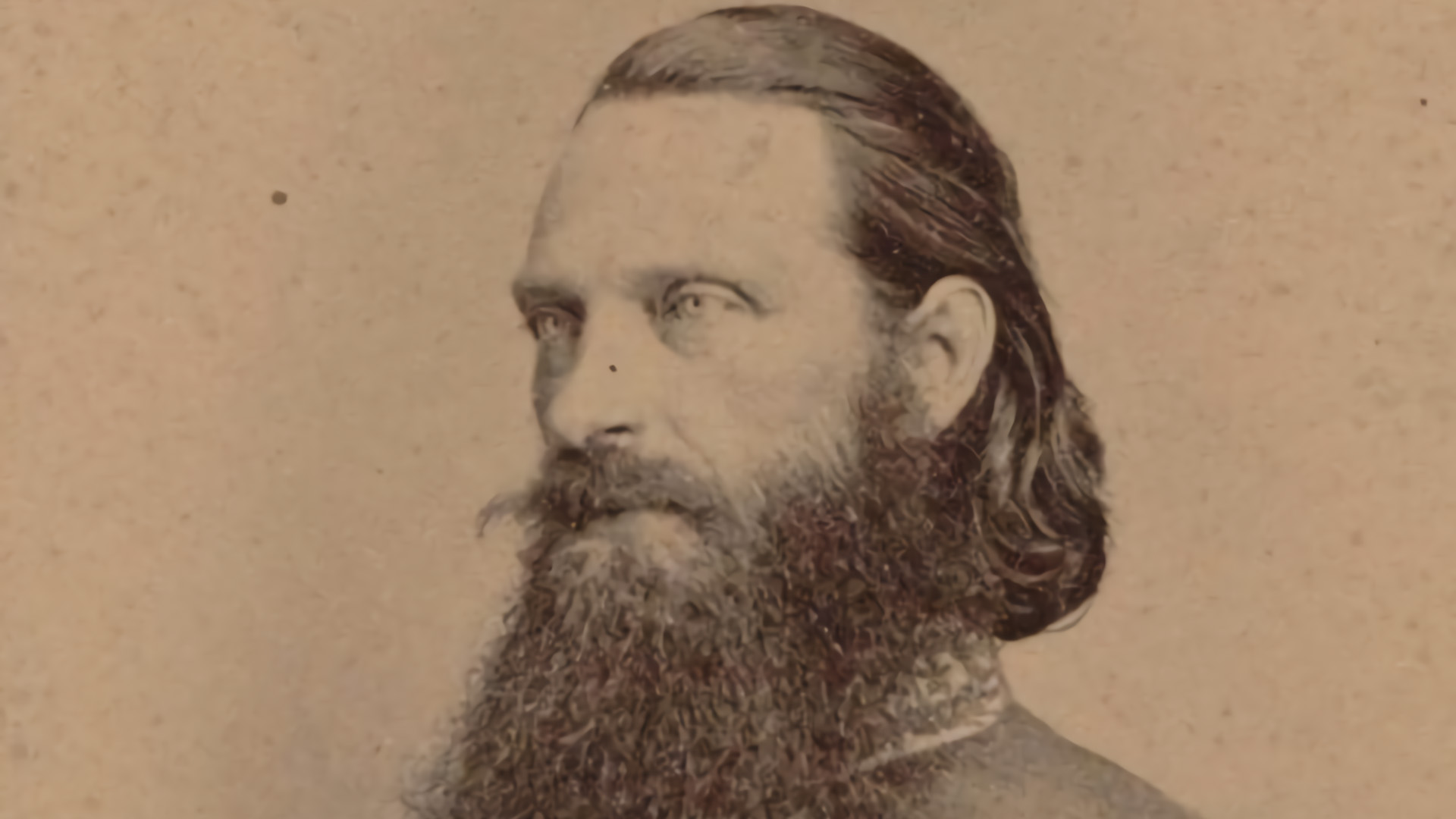

The general quartermaster was in his tent when suddenly the door flap was drawn open and a tall man in a blue uniform entered. It was the king himself, and despite the surprise appearance no one could mistake Charles XII for anyone else. The 26-year-old monarch had an oval face, lightly pockmarked with smallpox scars, and though young in years his face was weathered and tanned from years of campaigning. He wore his close-cropped hair naturally instead of the customary full-bottomed curly wig.

Charles came straight to the point. “In what direction do you think the army should march now?” he asked, his blue eyes boring into his quartermaster. This was a loaded question, and Gyllenkrok knew it. The original objective was Moscow, old capital of ancient Muscovy, as Russia was sometimes still called. But the Swedish offensive was stalled, in part because a vital supply train under Maj. Gen. Adam Ludwig Lewenhaupt was inexplicably delayed.

Winter was approaching and with it the end of good campaigning weather. Options were few, though fairly obvious and clear cut. The Swedish Army could try to find and ultimately link up with the supply train. It could also move south, into the Ukraine, where the countryside was rich and untouched by war. Then, too, allies might be found in the south, including some elements of the Cossacks, those hard-riding horsemen of the steppes.

Hedging his bets, Gyllenkrok said it was impossible to counsel Charles unless he knew what the king himself had in mind. “I have no plan!” the king replied, dropping a bombshell. Charles XII usually had a clear vision of his objectives, and once he decided on a course of action, nothing could persuade him to do otherwise. He had known what to do since this Great Northern War had commenced in 1700, eight long years earlier. And so far, militarily at least, Charles had been proven right more times than wrong.

But now Charles was at a crossroads. For the first time, perhaps in his whole life, he was truly uncertain about what to do. The whole campaign, perhaps even the destiny of the Swedish empire itself, rested on the decision he was about to make. Gyllenkrok, not knowing what to say on the spur of the moment, improvised and said it would be best if two other people were consulted about the matter. Charles approved, so Field Marshal Carl Gustav Rehnskold and Count Carl Piper were brought into the discussion.

Should the Swedish Army make a concerted effort to link up with the apparently struggling baggage train, or should it press on, going south into the literally greener pastures of the Ukraine? That would mean abandoning the drive on Moscow, whose capture was considered to be one of the key elements in a Swedish victory. Charles and his advisers reviewed each option carefully.

In the early 18th century Sweden was one of the great powers of Europe and, as such, was a splendid anomaly. It was an aberration because the nation only had approximately two million people. In contrast, the France of Louis XIV had 20 million souls. But a series of strong 17th-century monarchs catapulted Sweden into the front rank of Europe’s great nations. Gustav II Adolf, generally known as Gustavus Adolphus, laid the foundations in the Thirty Years War, in which he earned everlasting fame as one of the great military commanders of his age. King Charles X Gustav and Charles XI also made noteworthy contributions to the growing Swedish empire centered on the Baltic Sea.

The Swedish Army was also the cornerstone of the country’s rise to empire and political greatness. Charles XI established a fighting force that featured such innovations as the socket bayonet for the infantry. Swedish soldiers had iron discipline and were superbly trained and equipped. Their basic courage was reinforced by a firm Lutheran protestant faith that made fatalism a positive attribute. Most soldiers devoutly believed that God, not random chance or luck, was the prime factor in determining one’s fate. If it was not your time to die, you would emerge from battle unscathed.

Strong monarchs and a well-disciplined army ensured that the Baltic Sea remained a “Swedish lake.” In 1700 Sweden encompassed not only the country proper but Finland, Karelia, Estonia, Ingria, and Livonia. It also had footholds in Germany, including western Pomerania and the seaports of Stettin, Stralsund, and Wismar on the northern German coast. Most of the islands of the Baltic Sea were under Swedish control, as were as the bishoprics of Bremen and Verden.

But power politics has no morality, only self-interest. Sweden’s neighbors were envious and were waiting for a chance to seize plum portions of her empire. The opportunity presented itself when King Charles XI died of cancer in 1697 and was succeeded by his 15-year-old son, Charles XII. Charles was not only an adolescent but a seemingly irresponsible one, more interested in hunting, wildly galloping horses through the streets of Stockholm, and at least in one celebrated incident, getting dead drunk.

But these youthful indiscretions masked a keen intelligence and an iron will. Embarrassed by his behavior, he swore to his grandmother he would never get drunk again. He kept his word and for the rest of his life he would drink only weak beer, a little wine to make a toast, or svagdricka, which had very low alcohol content. He also loved olsupa, a soup that did contain a little wine or beer, but also had flour and eggs and was spiced with ginger and nutmeg.

Charles never wed. “I’m married to the army,” he declared. His self-discipline, ascetic lifestyle, and love of the military arts made him the perfect “husband” to his armed forces. Yet Charles was no barbarian. He read French, loved the plays of Moliere, and was fluent in Latin and German. But above all he was a soldier and would soon prove to be a gifted general with touches of real genius.

Hearing only of the king’s youth and inexperience, Sweden’s enemies were encouraged. In 1699 Frederick IV of Denmark, Peter I of Russia, and Augustus, elector of Saxony and king of Poland, entered into a secret alliance to dismember the Swedish empire. Frederick would attack Swedish possessions in the west, and the Poles and Russians in the east. The war opened with an attack by the Danes, but Charles took the news with scarcely a flicker of emotion, save for a steely resolve to defeat his enemies.

Charles first dealt with Denmark, surprising everyone by quickly moving into Jutland and threatening Copenhagen. King Frederick was soon forced to sue for peace. Having defeated Denmark in six weeks, the Swedish king now turned his attention to Czar Peter, who at that time was investing the town of Narva. Charles, landing with only 8,000 men, was faced with an entrenched Russian Army of 40,000. Using a blinding snowstorm as cover, Charles personally attacked the Russian Army and routed it. It was a brilliant victory that planted the seeds of the king’s legend as “Alexander of the North.”

Charles’s easy victory made him contemptuous of Russian fighting abilities and scornful of Russian generalship. Peter was vulnerable in the weeks immediately after Narva, but Charles turned aside and focused his attention on Augustus. For the next eight years Charles won victory after victory, often greatly outnumbered by his foes. Along with John Churchill, Duke of Marlborough, and Prince Eugene of Savoy, King Charles XII gained immortality as one of the great captains of the age of Louis XIV.

Charles pursued his enemies with the righteous anger of an Old Testament prophet. He never would have started a war, but, if attacked in an unjust war, he resolved never to stop until his foes were utterly vanquished. To Charles this war was unjust; it was a sudden and deliberate attack on a peaceful Sweden. Denmark, Poland-Saxony, and Russia started the war, and he resolved to finish it on Sweden’s terms.

The Swedish king eventually deposed Augustus and placed an ally, Stanislaus Lecycznski, on the Polish throne. At that point, Czar Peter remained the only enemy still active in the field. While Charles campaigned in Poland, Peter was far from inactive. He took Ingria along the Gulf of Finland, and in 1703 laid the foundations of St. Petersburg, soon to be Russia’s new capital and its so-called window to the West.

Charles’s Old Testament sense of moral righteousness, of being the wronged party, had served him well thus far, but then it led him to extremes. In 1707 the impetuous young monarch was at the height of his power, admired, feared, and courted by seemingly all of Europe. When Peter in effect sued for peace, offering to return all of the Russian-occupied territories of Livonia, Estonia, and Ingria except the St. Petersburg region and the Neva River, the king spurned this almost abject surrender, feeling the offer was insincere. Besides, Charles’s sense of righteous indignation demanded that Peter be humiliated and possibly even dethroned.

The Swedish invasion of Russia officially began in August 1707 when Charles moved out of his bases in Saxony. All Europe watched with breathless anticipation. Charles was now a legend in his own time, but Russia was still vast and largely unknown. The Swedish king led 44,000 men, the largest army he ever commanded; it was a veteran forced brimming with confidence in its young monarch and in its own abilities. Even German civilians were impressed. “I cannot express how fine a show the Swedes make: broad, plump, sturdy fellows in their blue-and yellow uniforms,” a Saxon admitted as he watched the long columns head east.

Czar Peter’s troops were in Poland, which meant the defense would begin well forward of the actual Russian border. More importantly, the geography favored the Russians. There were vast tracts of dense forests, and roads were few and primitive at best. And many of Eastern Europe’s great rivers are north-south in position, which made them effective barriers against any invader advancing from the west.

But in the early weeks these advantages were neutralized by Charles’s brilliant maneuvering. The king was a tactical genius whose almost instinctual feeling for topography served him well. Time and again he would outflank Russian troops, forcing them to withdraw. At the Vistula River in Poland the Swedes crossed over the newly formed ice, at the same time outflanking the Russians under Prince Alexander Menshikov in Warsaw and forcing them to abandon the Polish capital.

The Russians withdrew and formed another defensive barrier on the Narew River at Pultusk. Charles was unfazed. He led his army northeast, in effect sidestepping and getting around the Russian fortifications. The country was thickly forested and covered in marshes and viscous, quicksand-like bogs, which is probably why the Russians did not expect Charles to go that way. The march was indeed a nightmare, but the Swedes got through and crossed the Narew where the Russian defenses were virtually nonexistent. Charles and his long-suffering but hardy and confident soldiers had triumphed again.

Charles decided to cross the Neman River, the third river barrier, by means of a coup de main that reflected the king’s own personality: bold, innovative, and in some respects foolhardy. The key to the Neman River line was the Lithuanian town of Grodno, where a major bridge spanned the waterway. Charles galloped ahead with 600 troopers of his Guards cavalry.

Faced with his enemy’s inexorable advance, Peter fell back on a tactic that would be copied as late as World War II: scorched earth. The czar gave orders that all food and fodder for animals would be removed, burned, or hidden from the invaders. Towns and villages were put to the torch, and livestock were moved and hidden deep in the forest. Use of this tactic began in Poland and Lithuania, but even when Charles reached Russia proper, the harsh and unrelenting policy continued.

The Swedish Army finally went into winter quarters in February 1708 at Radoshkovichi, 25 miles northeast of Minsk. The Swedes were used to northern climes, but suffered from a lack of proper food, cramped conditions, and plunging temperatures. Dysentery swept through the camp; even affecting Charles for a time. Foraging parties found little to eat in the snowy forest wastes, and Lithuanian peasants were sometimes coerced by torture to reveal hidden caches of food.

As spring approached Charles had a look at the overall strategic situation. One day the king watched Quartermaster Gyllenkrock working on maps with a growing interest and excitement. “We are on the great road to Moscow!” Charles exclaimed, but Gyllenkrock said no, that was not quite the case, at least not yet. But it was plain that that was his ultimate goal: to vanquish Peter, capture Moscow, and dictate terms of peace at the Kremlin.

It was a heady dream, but a dream the supremely confident Charles felt was well within his grasp. “When we begin to march again, we shall get there, never fear,” the king replied. Taking his cue from Charles, Gyllenkrock prepared a line of march that would take the Swedish Army to Mogilev on the Dnieper. Once across the Dnieper River, the main road would lead to Smolensk and then to Moscow, the ultimate prize.

Moscow was to be the strategic objective, but the Swedish king was not going to let his enthusiasm get the better of him. There were practical considerations as well. The Russians were continuing their scorched earth policy, and it was still a long way to Moscow. How could he maintain his offensive under those conditions?

Charles summoned Lewenhaupt to his winter quarters to discuss the situation in March 1708, just before spring was due to arrive. Lewenhaupt was governor of Swedish Courland and was based in the fortress city of Riga. He had 12,000 men under his command, a force known as the Army of Courland.

Once again, Charles, not mincing words, issued orders that were straight and to the point: Lewenhaupt was to collect as much food and supplies as he could, form a huge wagon train, and transport the vital goods to the main army. Ideally, the general was to gather enough food and ammunition for his own men for three months and the entire army for six weeks. The wagon route chosen from Riga to Mogilev was 400 miles, and if he left Riga in early June, he would link up with Charles in two months.

Unfortunately, the assignment called for an officer who, like Charles, was ready to think creatively, a man who was ever ready to improvise and adapt to changing conditions. Lewenhaupt was capable of performing difficult tasks but tended to be unimaginative in independent command. He would faithfully carry out orders to the letter but nothing more.

Yet, by the same token, modern historians have pilloried Lewenhaupt for things that were beyond his control. It took a very long time to gather enough wagons and draft horses to fulfill his mission. He needed at least 8,000 animals to pull the projected loads and approximately 2,000 wagons also would be needed, and these vehicles could not be produced out of thin air.

Maybe Lewenhaupt was plodding and unimaginative, but the original timetables proved to be wildly unrealistic. It turned out the supply train was not even ready to leave until the end of June, almost a month behind schedule. Lewenhaupt remained in Riga for another month and did not join his convoy until July 29, when the supply train should have been very close to joining the main army.

Lewenhaupt’s progress was further hampered by the incessant rain, which turned the dirt tracks that passed for roads into a sea of mud. Heavily laden wagons bogged down, sinking into the mire almost up to their axles. Powerful draft horses, hooves flailing as they tried to gain purchase in the viscous, clinging mud, pulled the heavy loads to the point of exhaustion and beyond. Carpets of branches were laid on the mud, and wooden boards covered the worst spots, but progress was still slow.

In the meantime, Charles had begun his spring 1708 campaign with renewed vigor. The next obstacle was the Berezina River, which would figure so prominently in Napoleon’s ill-fated campaign of 1812. The Russians were determined to stop Charles dead in his tracks, and this river line seemed to be ideally suited to the purpose. However, the czar did not know exactly where the Swedes would attempt a crossing.

The Russian Army was stretched thin over a 40-mile front. Approximately 8,000 Russians were stationed at the Borisov crossing, the most obvious crossing point. Charles had no intention of doing the obvious. On June 16, after nine days of marching, the Swedish Army once again outflanked the Russians and threw up two bridges at Berezina-Sapezhinskaya. The move was detected by Russian dragoons and Cossacks, but there was no attempt to impede their crossing.

Charles marched on, but then received reports that the main Russian army had taken up position behind the Vabitch River, an area of swamps and marshes. Once again they were spread thin, but seemingly much better prepared. Green-coated Russian troops had literally dug in on the bank, and though some Swedish officers were still scornful of their Muscovite foes, Charles understood that the czar’s army had improved to a considerable extent. Once again Charles’s brilliance saved the day. His noticed that there was a marsh between two Russian divisions, and since it was undefended it was obvious the enemy felt it was impassible. The king led his men across the river at this point. Once across, there was still a lot of hard fighting to be done, but in the end this clash, which history records as the Battle of Holowczyn, was a Swedish victory.

The Swedish Army followed up its hard-fought win by moving on to Mogilev on the Dnieper River. It was July 9, and the peak of the campaigning season. Charles sent reconnaissance cavalry to scout the eastern bank, and the horsemen returned reporting that no opposition could be found. The way seemed clear, and once across the river, it was only 100 miles to Smolensk and from there 200 miles to Moscow.

Although the rank and file did not know it, Charles was waiting for Lewenhaupt’s supply train to join the main army. Day after day, week after week, Charles fretted and paced like a caged tiger. Where was Lewenhaupt? Every night the eastern skies were illuminated with an ominous orange smear that gave the horizon an almost surreal glow. It was the combined fires from burning villages that the Swedish Army might well have to depend upon for sustenance during its drive to Moscow.

It was plain that the march to Moscow would be dogged by starvation, because the czar’s scorched earth policy remained in full force. That made Lewenhaupt’s struggling column all the more important. The supplies he brought would enable the Swedish Army to cross what was becoming a picked-clean, barren wasteland with relative impunity.

But Charles was concerned that the long delay was taking the edge off the army’s offensive spirit. To that end, he launched a series of probing marches around the Dnieper region, first heading north, then abruptly turning south. If he was lucky, the Russians might be lured into a pitched battle, something that Charles was sure he could win handily.

Eventually the Swedish Army found itself in Tatarsk, where Charles began his series of consultations with Gyllenkrok, Count Piper, and Field Marshal Rehnskold. Common sense said that Charles should retrace his steps and go back to the Dnieper River, where he would be sure to meet Lewenhaupt’s supply column.

Once the union took place, Charles could resume his march on Moscow. There would be ample food and, as an extra bonus, Lewenhaupt’s additional 12,000 men would reinforce the main army. Yet Charles scorned this option. A retrograde march would be interpreted as a retreat, something the king found repugnant. Europe was watching, and the Swedes might lose face by retreating back to the great river. Moreover, Russian morale might rise even as his men’s morale plummeted.

But there was another option. He could turn south into the Ukraine. The region was rich, fertile, and untouched by war. And then, there was the matter of Ivan Stepanovich Mazeppa, Hetman of the Ukrainian Cossacks. These famed horsemen of the steppes were legendary fighters, and Mazeppa had been secretly negotiating with Charles to switch sides from Russia to Sweden.

Mazeppa might bring as many as 30,000 Cossacks to aid Charles, thus enabling the Swedish king to change course and renew his drive to Moscow. It was a heady scenario, and it helped Charles decided in favor of going south and temporarily abandoning his Moscow offensive. Couriers were sent to Lewenhaupt informing him of this change of direction and ordering him to a new rendezvous point farther south.

The Swedish Army began its march south on September 15, 1708. At that time Lewenhaupt was about 30 miles west of the Dnieper, and Charles was 60 miles east of the river. As soon as he received this information, Peter recognized that a golden opportunity was in the offing. There was a 90-mile gap between the two Swedish formations, and Charles was rapidly marching even farther south. The cumbersome wagon train, laden with desperately needed ammunition and supplies, would be vulnerable to Russian attack.

Acting with great swiftness, Peter ordered Field Marshal Boris Sheremetev to take the main army and continue to shadow the Swedish king as he went south. The czar had other plans for himself. Peter took personal command of the flying column, which consisted of 10 battalions of his best infantry mounted on horses as well as 10 regiments of dragoons and four batteries of horse artillery. The 11,625-man force included the elite Semenovsky and Preobrazhensky Guard Regiments.

After three long, grueling weeks on the road Lewenhaupt’s column finally reached the Dnieper on September 18. It took three days for the wagon train to cross the river. The Russians did not interfere, but red-coated Russian cavalry lurked in the woods. Lewenhaupt was acutely aware that his every move was being closely scrutinized. King Charles’s latest messages had reached him, ordering the general to turn south and head for Starodub, the new rendezvous point for the wagon train and the king’s army.

Lewenhaupt’s immediate goal was to get to Propoisk on the Sozh River. If he could cross the Sozh, he stood a fair chance of catching up with Charles. On the morning of September 27, Russian cavalry caught up and started skirmishing with the wagon train rear guard. A major engagement seemed imminent, and Lewenhaupt was faced with two choices. He could detach the rear guard to fight a holding action to delay the Russian pursuit, or he could halt and deploy his entire force for a set-piece battle.

Lewenhaupt chose to stand and fight, which in hindsight was a fatal error. He sent the supply wagons on ahead and formed his 12,500 infantry and cavalry into battle formations. They waited for an agonizingly long time, but still no Russian attack materialized. The morning and much of afternoon were utterly wasted.

When he finally realized that no attack was forthcoming, Lewenhaupt fell back farther down the road and reformed his battle lines. Still, though, the Russians did not cooperate. The Swedes stayed in battle formation all night. When there was still no attack by the morning of September 27, Lewenhaupt resumed his march, halting at the village of Lesnaya. But that time it was too late to escape the Russian clutches. The appearance of Russian dragoons meant that the Swedes would have to stand and fight.

Lewenhaupt had earlier dispatched 3,000 cavalry to secure the river crossing at Propoisk, but now it made little difference. Many Swedes in Lewenhaupt’s doomed command must have realized the terrible truth that if it were not for the previous wasted day and night, the convoy might have crossed the Sozh and eluded its pursuers. In war circumstances change rapidly, and one wrong decision, no matter how seemingly valid at the time, can lead to disaster.

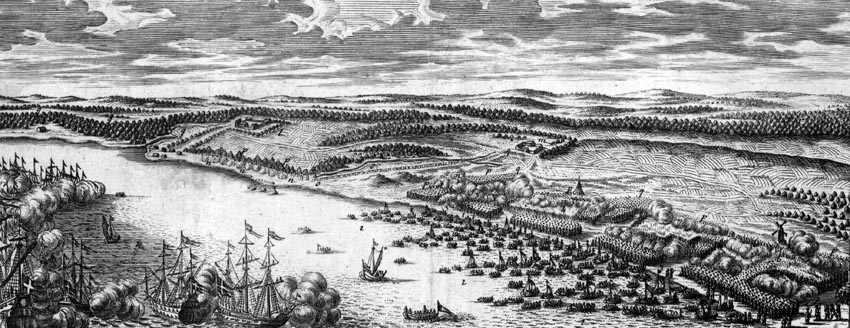

Lewenhaupt formed his defensive lines just north of Lesnaya village. The region was thickly forested, but the ground just in front of the village was an open field, so some maneuver was possible. The Russian dispositions were simple. Generalissimo Prince Alexander Menshikov took over the Russian left flank with three battalions of infantry and seven dragoon regiments. Czar Peter commanded the right, with two Guard regiments and one battalion of infantry. He also controlled the Russian reserve cavalry.

The battle commenced at 1 pm. From the beginning it was clear that there would be few displays of tactical brilliance on the field. No one—not the czar, Menshikov, or Lewenhaupt—showed any signs of superior generalship. This was a soldier’s battle, with masses of infantry slugging out volley after volley, charge after charge, in a seeming test of will.

At one point Menshikov ordered an advance to exploit a gap he perceived in the Swedish line, a hole created by the heavily wooded terrain. The green-coated peasant soldiers surged forward, only to be sent packing by a spirited charge of Swedish cavalry. The Russian foot soldiers sought refuge in the nearby forest, where the thick branches and sun-dappled leafy ground made it a perfect place to hide.

But their retreat weakened the Russian line and it looked like the Swedes were at the point of breaking through. But Czar Peter propped up the Russian line by sending in the Semenovsky Guard Regiment to put an end to the crisis. And so the battle seesawed back and forth, with no clearcut winner. “All day it was impossible to see where the victory would lie,” noted the czar.

At 4 pm Russian cavalry under Lt. Gen. Adolf Bauer arrived on the scene and launched an attack on the Swedish right flank. Hard pressed, the bluecoated Swedes were forced to give ground, though they were far from routed and certainly not defeated. They did retreat behind a series of protective earthworks that had been thrown up around Lesnaya. The fighting sputtered out and effectively ended by around 8 pm. A freak snowstorm, unusual for this early in autumn, also helped the combatants to call it quits.

The Swedes had thus far held their own, and at best the battle might be called an inconclusive draw, but Lewenhaupt’s pessimism soon spread throughout his command. He decided to abandon the wagons and their precious cargoes, making sure that everything was destroyed so it would not fall into the hands of the enemy. Cannons were removed from their carriages and buried. Given their massive weight, this was no easy task.

As evening fell the wagons were put to the torch. Collectively, the burning wagons seemed to be the funeral pyre of Swedish hopes and Charles’s aspirations. Though perhaps the common soldiers could not articulate it, they probably felt the same. The despairing hopelessness became manifest in a breakdown of Swedish discipline.

Some wagons were not destroyed because they carried officers’ possessions. Common soldiers lost no time in looting the contents, freely imbibing the brandy and other spirits they found there. Many became dead drunk and later died of exposure or from Cossack and Kalmuck swords and lances. Lewenhaupt ordered a retreat to Propoisk, but the iron bonds of discipline, one of the Swedish Army’s greatest strengths, broke down completely. Some regiments still retained some cohesion, but others melted away into small bands and roamed the woods.

When some of the surviving Swedish regiments reached Propoisk they found the bridges had been burned. Many still managed to cross, but 500 were caught on the river banks and slaughtered by Cossacks. Incredibly, a rag-tag group of 1,000 men actually marched back to Riga, a distance of 800 miles. Approximately 3,000 others were taken prisoner by the Russians.

General Lewenhaupt actually managed to reach Charles and the main army, but with no supplies and 6,000 starving survivors, half of his original force. The king took the news with his customary stoicism, and though this was a heavy blow, he still might have emerged victorious in the coming months. But it was not to be.

Unfortunately for the Swedes, the Russian campaign would ultimately end in disaster, and in retrospect Lesnaya was the beginning of the end of Charles XII’s extraordinary career. King Charles’s alliance with Mazeppa ultimately proved disappointing. What is more, the winter of 1708-1709 was one of the harshest ever recorded, so cold it was said birds fell frozen from the trees. Peter’s Russians and Charles’s Swedes clashed at Poltava. The battle was a decisive victory for Russia and a catastrophic defeat for Sweden. Peter’s victory heralded the arrival of Russia as a European power.

The Battle of Lesnaya is important not just because it denied Charles of Sweden vital supplies and doomed his drive on Moscow. Its psychological significance is just as great, perhaps even greater, than its strategic importance. “This victory may be called our first, for we have never had one like it,” Peter observed. “It put heart into our men, and was the mother of Poltava.”