By Eric Niderost

Agroup of insurgents, probably abolitionists fiercely dedicated to ending slavery, had seized the Federal Arsenal at Harper’s Ferry—that was the news Charles W. Welsh, Chief Clerk of the Navy Department, had for the officer in charge of the Marine Barracks at the Washington Navy Yard. At noon on Wednesday, October 17, 1859, the senior line officer present at that moment just happened to be First Lieutenant Isaac Greene.

Promotion in America’s military was notoriously slow; though only a Lieutenant, Greene already had served a dozen years in the Marine Corps. Welsh lost no time in briefing Greene about the developing crisis at Harper’s Ferry. Situated at the confluence of the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers, the arsenal was a cluster of buildings that also included an armory. Nearby was the Hall Island Rifle Factory, another tempting target for would-be insurrectionists.

Welsh explained that the nearest regular army troops had been dispatched from Fort Monroe, a journey that was likely to take two days. This emergency needed a rapid response. “How many Marines were available for immediate service?” Welsh asked. Greene took a moment to add the numbers on duty and those still in the barracks. “About 90,” he said.

Now it was Welsh’s turn to calculate. The crisis was real, but panic combined with wild rumors tended to exaggerate the numbers of “insurgents.” Some reports put the number of armed abolitionists in Harper’s Ferry at 200. But the necessity of sending federal troops as quickly as possible overrode all other considerations.

Satisfied, Welsh left to get Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey to formally approve use of the Marines while Green began preparations for the expedition. There would be 86 Marines in all, each armed with a model 1842 rifled musket. They would also bring two 3-inch howitzers which, if needed, would be put to good use as Greene was an artillery instructor for the Corps.

In the late 1850s the U.S. armed forces were ending a tumultuous decade of Indian war and civil strife. The U.S. Army was often despised by the public in times of peace and starved of funds by a parsimonious Congress. Its chief mission was to defend the republic against enemies foreign and domestic, the latter often meaning indigenous tribes trying to save their lands and cultures from the white tide of settlement.

The Army won new laurels in the Mexican War of 1846-1848, but its success created new problems and added responsibilities. As the nation extended to the Pacific, the U.S. Army now had to safeguard some 2 million square miles of territory—much of it wilderness beyond navigable rivers, roads, or existing railroad lines.

It was tough enough dealing with the Plains tribes, but in the mid-1850s the American military had to take on the problems that increasingly arose as Kansas was opened for settlement. The immediate cause of the trouble was the Kansas-Nebraska act of 1854, a law that in effect abolished the old line—36 degrees, 30 minutes—separating the free North from the slave-holding South. Instead, a concept known as “popular sovereignty” would determine if a new territory would ultimately become a free or slave state. The people of a new territory themselves would determine if they wanted slavery or not, free from any meddling from Congress or the federal government. On paper it seemed the epitome of democracy, but in practice it was to prove a pandora’s box of increasing complexity and growing violence.

Southern cotton production was indelibly linked with African American slaves and as plantation profits soared, southern apologists lost no time in defending their “peculiar institution.” Abolitionism—the movement to end slavery in America—gradually gained momentum in the north, though it was still only a vocal minority. But even if most northerners were indifferent to the plight of slaves, they did fear slavery as an institution that would compete, and ultimately degrade, free labor. For that reason, virtually all northerners were adamantly opposed to the spread of human bondage.

The Kansas-Nebraska act decreed that Kansas would be free or slave according to the wishes of the majority of its residents. The New England Emigrant Aid Company was formed to assist new Free-Soil settlers into the contested territory. Missouri, a slave state that bordered Kansas, had the advantage of geography.

“Come on, Southern men!” a proslavery newspaper urged, “Bring your slaves and fill up the territory!”

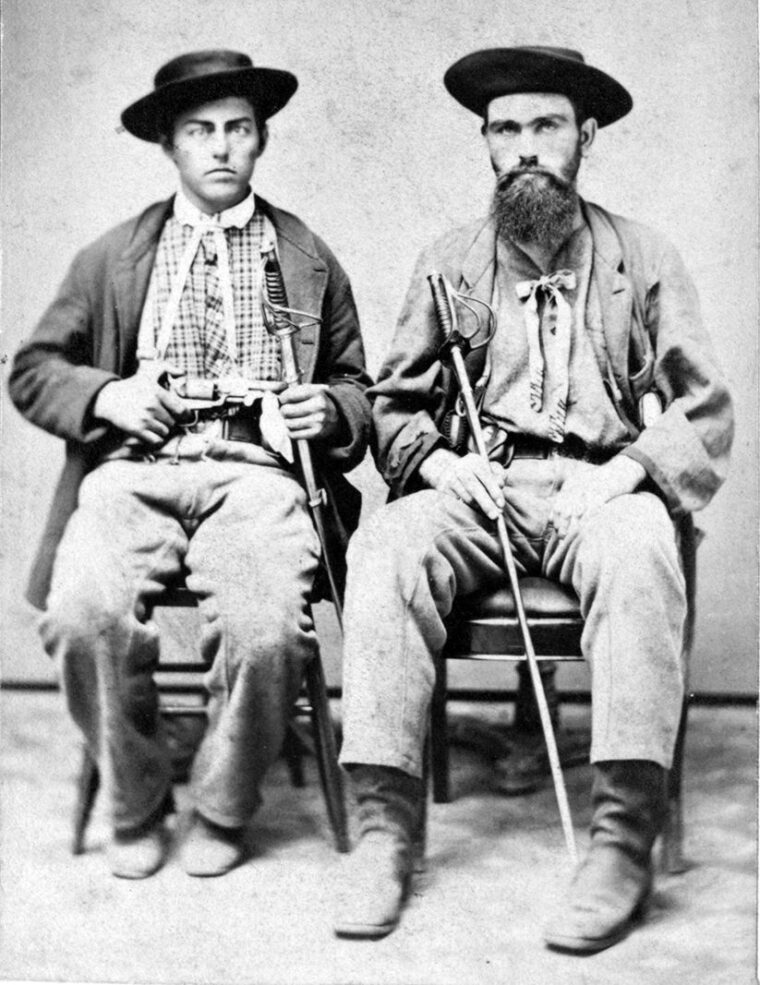

When an election was going to be held to form a territorial legislature, thousands of Missourians flooded into Kansas to vote illegally. Missouri Senator David Atchison personally led a group of illegal voters—called “Border Ruffians” by northerners—into Kansas.

“There are eleven hundred men coming over from Platte County,” Atchison gloated, “and if that ain’t enough, we can send five thousand!”

Predictably, the pro-slavery faction won an overwhelming victory and soon established a territorial legislature at Lecompton, Kansas. President Franklin Pierce, called “doughface” because of the perception that he could be molded to any position the south wanted, dismissed the allegations of fraud and recognized the Lecompton lawmakers as the only legitimate government of the territory.

Northern Free Staters, refusing to be cowed, responded by quickly drawing up a Free-State constitution and calling for another election for a legislature and governor. The pro-slavery faction boycotted this election, which predicably led to the creation of a Free State territorial legislature.

In early1856, Kansas had functioning legislatures at Topeka (Free State) and Lecompton (pro-slavery). Despite the official endorsement of the Pierce Administration, the Lecompton legislature was based on fraud and illegal voting. By late 1855, Kansas residents who originally hailed from the north far outnumbered those from the south. That meant the Topeka government, scorned by the Pierce Administration as extralegal and illegitimate, actually reflected the real majority wishes of the Kansas population.

In the meantime, Congress relented and decided to boost army numbers by adding two regiments of infantry and two of cavalry. At the time there were three regiments in the regular army: The First Dragoons, Second Dragoons, and the Mounted Riflemen. The new units would be designated the First Cavalry and the Second Cavalry. The First would be organized in the spring of 1855 and commanded by the newly promoted Colonel Edwin V. Sumner.

Sumner was an excellent choice, a man who was well respected, competent, and seasoned by many years in a service he genuinely loved. The First Cavalry would be stationed at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, while the Second Dragoons would be posted at Fort Riley. These Federal Army troops soon found themselves in the center of an unprecedented political maelstrom, the calm “eye” of a swirling hurricane of sectional strife.

The first violence occurred when a Missourian killed a Free Soil settler over a disputed land claim. The murder set off a series of incidents that threatened the overall peace of the troubled Kansas territory. Unfortunately, the current Kansas governor was Wilson Shannon, a political hack guided by the strict instructions of U.S. Secretary of State William Marcy—request federal troops only as a last resort, and even then, only to assist U.S. Marshals in the performance of their duties of serving warrants, conducting arrests, and so on.

At the same time, Colonel Sumner was getting orders from Secretary of War Jefferson Davis. The man who would later become the president of the Confederacy was a stickler for the rules, insisting that Sumner’s federal troops were only to act at the request of Governor Shannon and only as support for U.S. Marshals. Even then, the army was supposed to act only when the U.S. Marshals were unable to suppress an insurrection themselves.

Under no circumstances was the Army to act as a constabulary. Many American institutions and political attitudes had formed as a reaction to colonial British rule. One of these was an abhorrence of professional standing armies as potential servants of tyranny and instruments of despotism.

Things came to a head when Shannon called out the militia to “restore order.” Happy to have official sanction, the pro-slavery Kansas militia besieged Lawrence, the Free Soil bastion of the territory. Lawrence was ready for any assault; some 800 Free Soil militia, some armed with the new sharps rifle, took up defensive positions.

Desperate appeals by Shannon, coupled by bitter December weather, eventually defused the conflict. The siege was lifted and the militias went home. But the situation was still volatile, with both sides determined to win over Kansas, even at the cost of bloodshed.

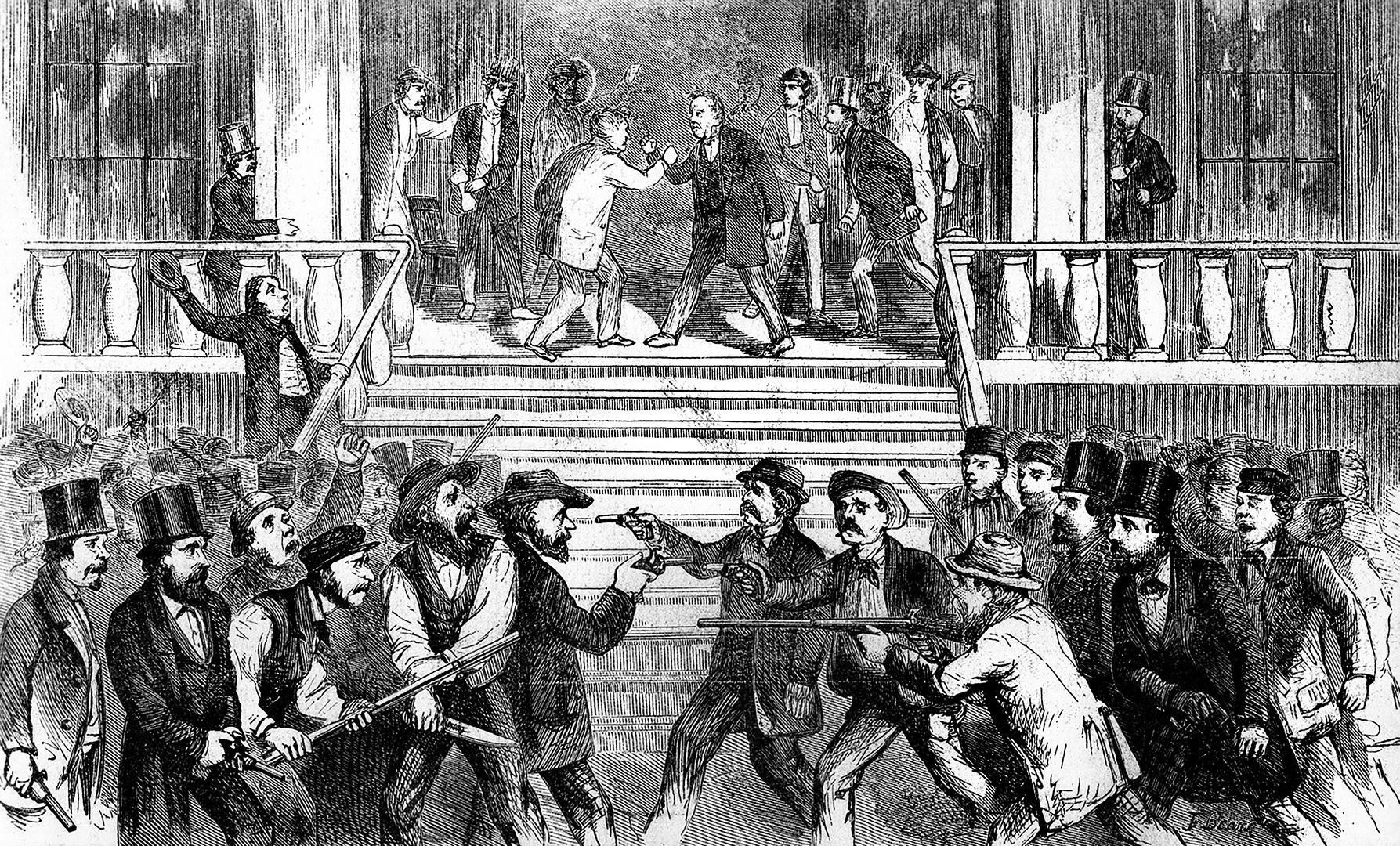

The pro-slavery forces again descended on Lawrence, this time taking it by surprise and virtually defenseless. David Atchison was the leader of this group of Southern avengers, and by his own admission, “this is the happiest day of my life.” He was exultant, and quickly added “If one man or woman dare stand before you”—offers resistance—“blow them to hell with a chunk of cold lead.”

The slavery men responded with a cheer, and set to work sacking Lawrence with a thoroughness that the survivors long remembered. The invaders came into town proudly flying flags emblazoned with such slogans as “Southern Rights” and “White Supremacy.” The offices of abolitionist Kansas Free State and the Herald of Freedom newspapers were destroyed, the printing machinery smashed, the type thrown into the river.

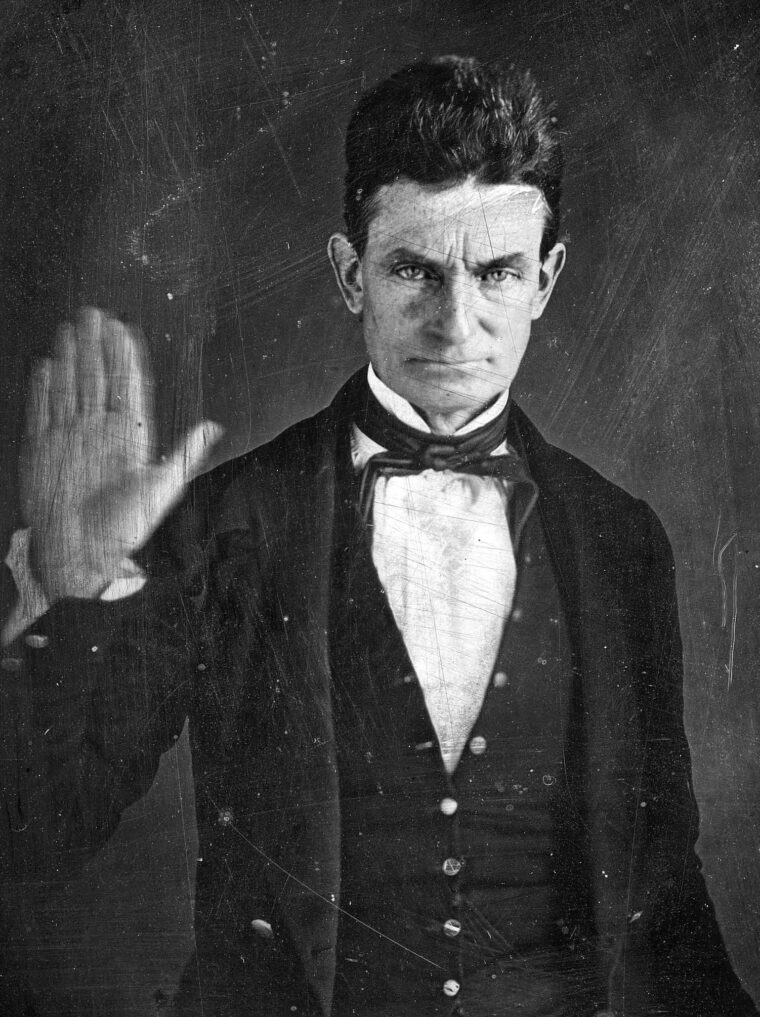

The sack of Lawrence created a sensation, and one of the men who vowed revenge was John Brown. A resident of Kansas since 1855, Brown was from New England. He owned a successful tannery for a time, but his restless spirit sought something more. Brown eventually became active in the abolitionist movement and was known as a man who not only wanted to end slavery, but was dedicated to making African Americans equal in both society and in law.

Not long after the sack of Lawrence came the news that Senator Charles Sumner (a distant relative of General Sumner) had been beaten nearly to death in the Senate chamber in Washington by Preston Brooks, an enraged southern Representative. Brown also knew that at least two Free Soil men had been killed in Kansas, and he wanted to even the score. To Brown, the killings he planned were not murder, but righteous executions that had a biblical, eye-for-an-eye flavor to them.

With the mercilessness of a true zealot, Brown dragged five men out of their cabins on the night of May 24-25, 1856 and slaughtered them with a brutality that shocked the nation when it became known. Some of the victims were shot, others were hacked with the broadswords. John Doyle, who was spared by the attackers, reported that when he found his brother’s dead body the “arms were cut off; his head was cut open and there was a hole in his breast.”

The incident, dubbed the “Pottawatomie Massacre,” set off a chain reaction of violence that brought Kansas territory to a state of near anarchy. For the next three months Kansas entered its bloodiest period, with 29 killed due to internecine strife. Shannon was now willing to dispense with legal wrangling, and even President Pierce, appalled at the growing violence under his watch, was more willing to use the army to restore order.

Sumner welcomed the change, and accepted Shannon’s plan to clear roads and check invasions—any invasions, north or south—with regular army troops. The gloves were off, but the gauntlets were on and the troopers were in the saddle. The soldiers were now constabulary, with police duties that did not require a U.S. Marshal. Their new duties were dangerous; ambushers wounded one trooper and two horses near Lawrence.

Henry Clay Pate, a newly commissioned Deputy U.S. Marshal, was a passionate pro-slavery man who made it his mission to track Brown down for the Pottawatomie massacre. Pate assembled about 50 men and set off in search of the now-notorious Free Soil leader. Brown welcomed a fight, and when he felt the time was right he halted and formed his 30-odd men into a skirmish line. Pate’s men came up and soon there was a lively—if sporadic—exchange of fire for the next two hours.

Eventually Brown’s men got the better of the Pate posse—for the most part, Missourians—and one of them attached a white flag to a ramrod and waved it. Pate himself seized the white flag, stood up, and said “We are government officers sent out in pursuit of criminals. You are fighting against the United States.”

Brown, who initially didn’t see the white flag, replied, “If that is all you have to say, I have something to say to you. I demand of you unconditional surrender.” As he said these words Brown leveled his weapon at Pate. One of the Missourians shouted, “We don’t surrender until our captain (Pate) gives the order.” The Missourians cocked their weapons and pointed them at Brown.

Unfazed and unintimidated, Brown called to his men “Put a dozen balls through the first man of them that shoots.” As if to underscore his fearlessness, Brown put the muzzle of his colt revolver so close it almost touched Pate’s chest. “Give the order (to surrender),” Brown demanded. After a moment that must have seemed like an eternity, Pate surrendered.

Brown didn’t have his prisoners in custody for long. The ever vigilant Sumner found out about the clash between Pate and Brown—now known as the Battle of Black Jack—and decided to take action. He personally led 50 dragoons to Brown’s camp on Ottawa Creek, taking a U.S. Marshal with him to cover any legal issues that might arise.

Sumner told Brown he must disperse and release his captives immediately. Pate and the others were freed, and admitted they had been well treated when in custody. Sumner also broke up a party of some 250 pro-slavery men under J. W. Whitfield whose intention was to rescue Pate. It is not known what Brown said to Sumner when they met, but the abolitionist had no real intention of disbanding his group.

A few weeks later Sumner was given what he admitted was the hardest order he ever had to obey as an officer of the United States Army, namely the disbanding of the free state Topeka legislature. Governor Shannon had instructed Sumner to “disperse” the legislature “peaceably if you can, by force if necessary.”

Ironically, the date given for the action was July 4, 1856. The Free Soilers were notified of Sumner’s approach when a man came into Constitution Hall where they were meeting and announced “the regulars are coming.” Here was another irony, for these were the same words Paul Revere used to alert citizens the British soldiers were on the move.

Hundreds of Free Soil men women, and children were on hand to watch the cavalry troopers ride in, disciplined and orderly. Sumner himself was an imposing figure, ramrod straight in the saddle, with a piercing eye and well trimmed black beard. He gave orders in a booming voice—hence his nickname “bull of the woods”—that echoed down the street.

Sumner reassured the group that he was here to send them home, not to disarm the local militia, a statement that produced a round of “cheers” for the soldier. Dismounting, he walked into the building and proceeded to the legislative chamber where the Free State politicians had assembled. He asked the legislators if they wanted to make him speaker, a small joke that nevertheless eased the tension and produced gales of laughter.

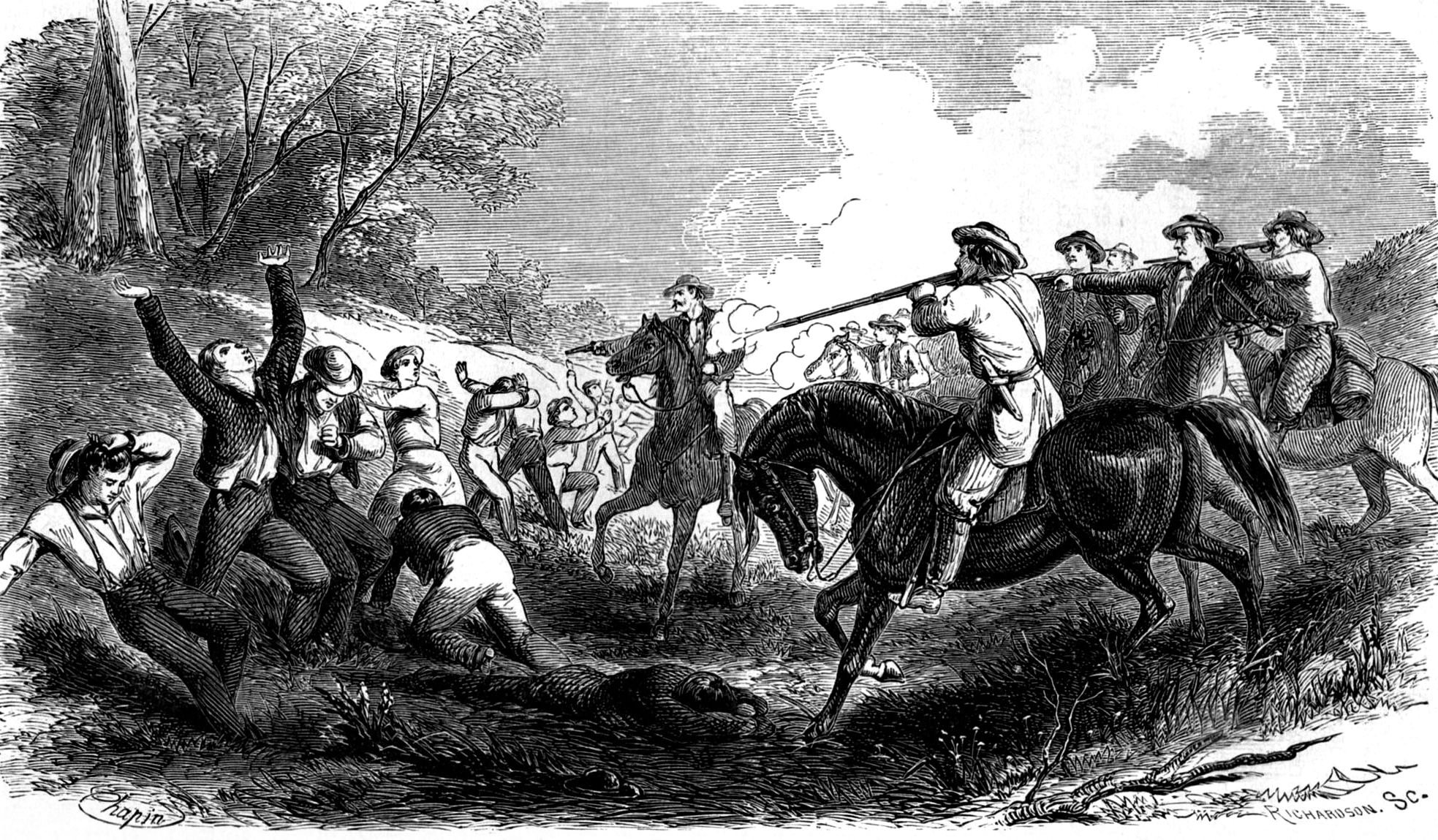

The Free Soil legislature went home, but the setback was only temporary. John Brown and his partisans were still active. Determined to win Kansas for slavery once and for all, JohnW. Reid and an army of more than 300 Missourians headed for Osawatomie, another Free Soil stronghold. On the morning of August 30, 1856, the Missourians approached Osawatomie, and in the early fighting Free Soiler David Garrison and Brown’s son, Frederick, were killed.

Brown was outnumbered seven to one, having only about 38 men, but he handled the situation with skill and courage. By using natural cover and displaying good marksmanship, Brown’s men put up a surprisingly effective defense. At least 20 Missourians were killed, and more than 40 wounded, but at last sheer numbers began to tell. Brown and his men retreated over the Marais des Cygnes River and the Missourians turned to sack and burn Osawatomie.

Brown paused for a moment to look at the flames engulfing Osawatomie, and his son Jason saw tears running down his cheeks.

“I only have a short time to live, and one death to die, and I will die fighting for this cause. There will be no more peace in this land until slavery is done for. I will give them something else to do than to extend slave territory. I will carry the war to Africa.” To Brown, the rhetorical “Africa” was the slave states, where slavery was legal and accepted.

By 1857 a fragile peace had been established in “Bleeding Kansas.” A tough new Territorial governor, John W. Geary, used the U.S. Army in a series of pre-emptive moves that snuffed out the burning embers of discord before they could ignite into a full scale conflict. Sometimes even Colonel Sumner had been reactive, responding to violence that already occurred, as when he went to free the prisoners after the so-called Battle of Black Jack.

With Kansas largely pacified, and a price on his head for the Pottawatomie killings, John Brown left Kansas in early 1858. For a good 20 years, he had dreamed of a slave rebellion in the south—now he was determined to make that dream a reality. There are several different versions of what he had in mind, perhaps the recollections of the great black abolitionist Frederick Douglass comes as close as we will ever get to Brown’s overall scheme.

Brown envisioned a small cadre of men, no more than 25 or so, that would be the foundation of the slave rising, partisan leaders who would be natural magnets for slave recruits to flock to in their desire for freedom. They would be sent out, apostle-like, to spread the word and gather recruits throughout the south.

He would create a mountain stronghold in the Blue Ridge, Virginia’s part of the Appalachian chain, the first of many such “safe places,” each a base and an inspiration to revolting black slaves. Brown needed guns and ammunition for the thousands he hoped would flock to his banner. He already had a stockpile of weapons, purchased from funds donated by abolitionists. Brown for some reason was prejudiced against the new Sharps repeating rifle, and ordered pikes for the slaves to arm themselves.

Nevertheless, the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia (now West Virginia) seemed a logical choice to get additional arms and ammunition. There were around 100,000 rifles and muskets there, and untold quantities of ammunition. Seizure of the arsenal might also give encouragement to the slaves and correspondingly strike fear in the hearts of their masters.

The next two years were anything but easy for Brown. By nature bold and swift, he was forced by circumstances to be furtive and patient.

“One of the U.S. Hounds (marshals) is on my track,” he once complained, “and I have kept myself hid for a few days to let the track grow cold.” He was also plagued by ill health. Malaria, endemic in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys, kept him in bed for weeks at a time.

Luckily for Brown, modern police detective work was in its infancy. He grew a long beard to disguise his identity, and used a variety of aliases—Nelson Hawkins and Ian Smith, for instance—that served him well in his peripatetic life. As time went on, the raid on Harper’s Ferry seemed more and more quixotic. Frederick Douglass pointed out that Harpers Ferry was surrounded by mountainous peaks, and the few roads or bridges in and out of the town could be easily blocked by authorities. The idea that 25 men would be enough to take on the state of Virginia, much less Federal government, also seemed suicidal, and the bad publicity would hurt the abolitionist cause.

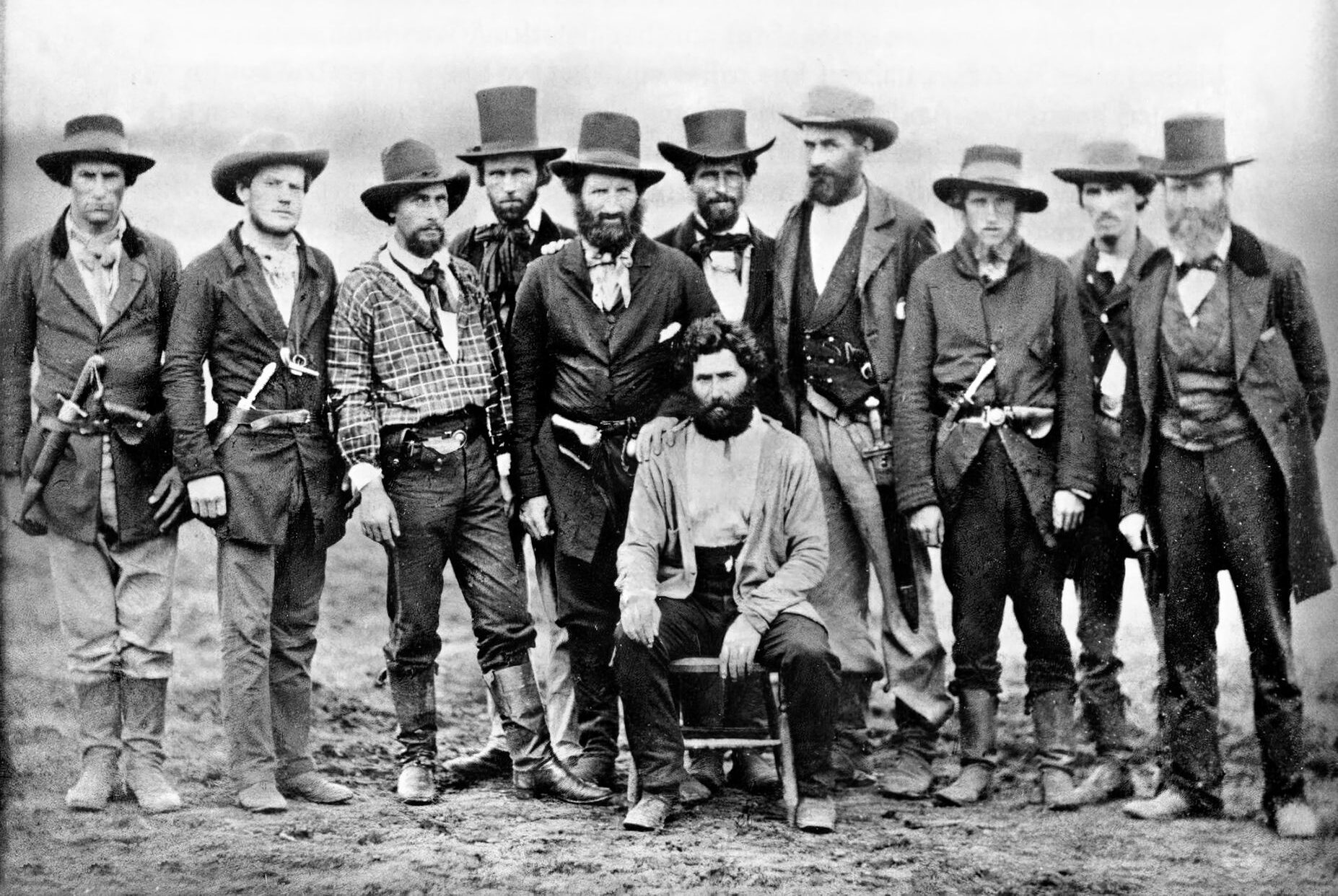

Brown went ahead with his plans, and managed to rent a farm in nearby Maryland as a base of operations. Locals suspected nothing, and some felt the men they saw coming and going were part of a fledgling mining operation. Brown’s men, who he dubbed the “provisional Army,” had 22 members, counting himself. The Harper’s Ferry expedition set out about 11 p.m. on Sunday, October 16, 1859. Three men, including his son, Owen Brown, were left behind as a kind of rear guard and also to keep watch over their cache of weapons.

Brown detached a few men to seize some hostages and free local slaves. One of their main targets was Colonel Lewis Washington, grand nephew of George Washington. They captured Washington without a struggle, and also took one of George Washington’s swords, given to him by King Frederick the Great of Prussia. When they arrived with the prisoners, about a dozen in all, Brown appropriated the sword, considering it a talisman of victory.

After the hostage gathering party was dispatched, the rest crossed the Baltimore and Ohio railroad bridge that spanned the Potomac River and soon found themselves in Harper’s Ferry. Brown made sure some men were posted to control both the Potomac and Shenandoah River bridges that led into the town. The Armory was quickly taken, and the single watchman was surprised and taken prisoner without incident. More hostages were taken, till the number of captives stood at about 60.

Heyward Shepherd, a Harper’s Ferry train station baggage handler, felt something was amiss and started walking over the railroad bridge in search of the night watchman. It was about 1:15 in the morning, and still pitch black. A call to halt came out of the inky void, but Shepherd chose to ignore the command and turned back to the station. One of the raiders, perhaps thinking he would spread the alarm, shot Shepherd in the back of the neck.

A local doctor, who by chance lived nearby, heard the commotion and did what he could for the stricken baggage porter, who later died of his injuries. Ironically, Sheperd was a free African American. But it was 1:30 a.m. when the Baltimore and Ohio “Through Express” train rolled into Harper’s Ferry. Brown took the train, but let it proceed to Washington D.C, a blunder of colossal proportions that sealed the fate of the raiders.

The train spread the alarm, and the news reached the desk of Secretary of War John B. Floyd, who immediately telegraphed the nearest available federal troops at Fort Monroe. By noon Captain Edward Ord with 150 Artillerymen would be on the way, but would take them a couple of days to arrive—much too late.

That’s when the idea of using the U.S. Marines came to the fore. But Floyd realized that the Harper’s Ferry expedition needed a senior officer to direct operations. He remembered that Brevet Colonel Robert E Lee of the Second Cavalry was on leave at his Arlington home, just across the Potomac River from the capital. By chance another cavalry officer, J.E.B. Stewart, was sitting in Floyd’s outer office, waiting to be seen on another matter and barely able to cope with the boredom of his situation.

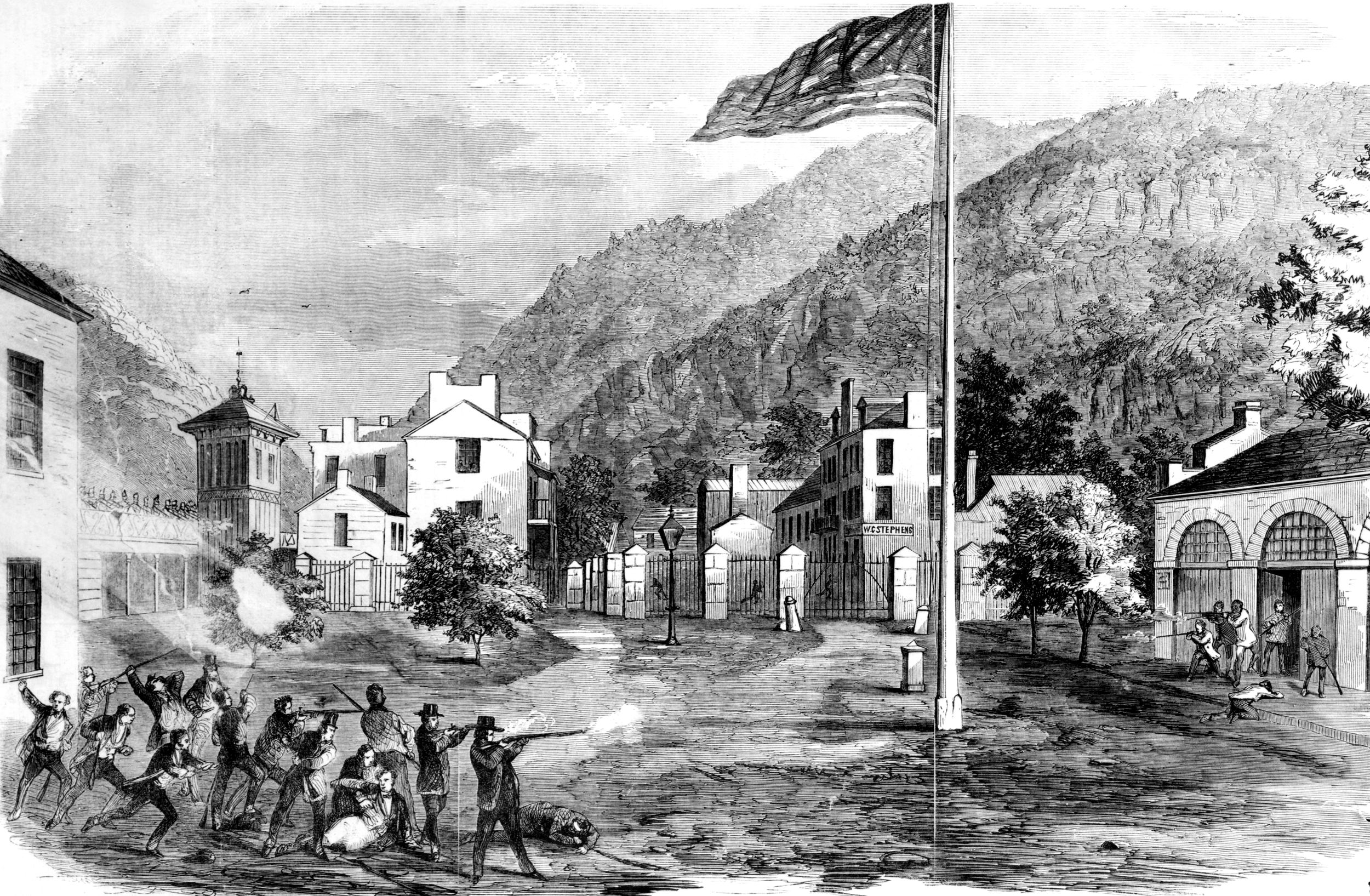

Stuart was recruited to send a message to Lee, which he was more than happy to do. Colonel Lee accepted the assignment, and took Stuart along as an informal aide de camp. In the meantime militia units had already been arriving at Harper’s Ferry, and their sheet numbers, if nothing else, forced the raiders to abandon many of the buildings they formerly occupied and concentrate on the brick engine house.

Brown had lost the initiative, and by waiting too long, was now trapped in the engine house, where the armory’s fire engines were stored. The raiders used the two fire engines and hose cart to block the heavy doors. They reinforced the doors with rope and knocked loopholes in the walls to exchange fire with the militia. The exchanges of gunfire, though sporadic, were often very heavy.

During the course of the day four townspeople were killed, and eight militia wounded. One of the fatalities was the Mayor of Harper’s Ferry. The Virginia militia proved to be an embarrassment, upsetting state Governor Wise. They were a poorly armed, disorderly mob, and frequently “roaring drunk.” Worse still, they also seemed a cowardly rabble, whose performance the Charleston Mercury labeled a “broad and pathetic farce.”

Brown sent his son Watson and raider Arron Dwight Stevens out with a white flag; it was not honored by the militia, who mortally wounded Watson and captured his companion. Another son, Oliver, was also mortally wounded during this time. The raiders who had been posted outside the engine house were killed or wounded, and the hostages held there rescued. Only Brown and a handful of raiders held out.

Brown’s raid had reawakened memories of the 1831 Nat Turner slave rebellion, when 55 whites, men women and children, had been killed by slaves. This latent fear, hidden just below the surface of antebellum southern society but always present, produced a rage that manifested itself in a callous brutality. When African American raider Dangerfield Newby was killed, his ears and genitals were cut off “for souvenirs,” and the corpse was cut open. His body lay in the street for a long time, permitting neighborhood hogs to rend the corpse and eat their fill.

The Marine detachment boarded a special train at 3:20 p.m. that same Monday. To underscore the importance of their mission, their departure was witnessed by President James Buchanan, Secretary Floyd and Secretary Toucey. Colonel Lee and his aide J.E.B Stuart took a later Baltimore and Ohio train. Lee was in civilian clothes, not having a uniform available in time, while Stuart had to borrow a uniform coat.

Lee and the marines arrived the night of Oct. 17, but it was late, so Lee decided to wait until dawn before dealing with Brown and the desperate raiders holed up in the engine house. The next morning, his basic attack plans formulated, Lee asked the local militia if they would like to lead the assault. They declined, so the job was given to Lieutenant Greene and the Marines.

Brown would be given the chance to surrender—but unconditionally. Lieutenant Stuart would deliver Lee’s terms under a flag of truce. If Brown refused, Stuart was to wave his hat as a signal to begin the assault on the engine house.

There would be 12 men in the storming party: a sergeant, a corporal, and 10 privates, with another 12 marines to act as a reserve. In addition, two sledgehammer wielding marines would provide the muscle—literally and figuratively—to batter down the engine house doors. Word of the Brown raid had spread far and wide, and as many as 2,000 people gathered at Harper’s Ferry to witness history being made.

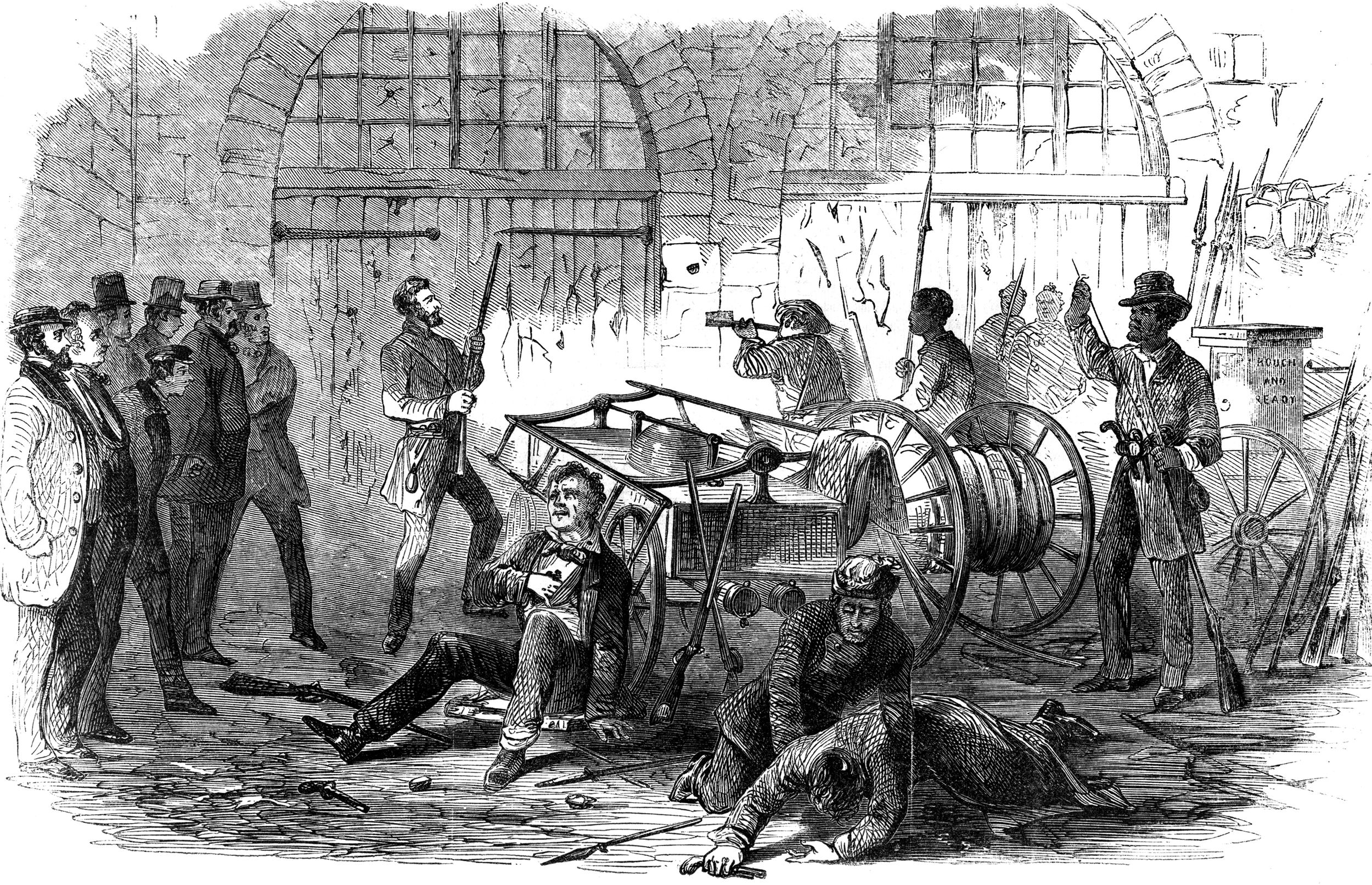

Brown and Stuart had a parley, but as expected “Old Osawatomie,” as he was sometimes called, refused to surrender. Stuart waved his hat as a signal to advance, and the marine storming party surged forward. The sledgehammer men pounded away, but the door resisted their best efforts. The raiders had reinforced the door with ropes and braced it with hand brakes from one of the engines.

Even with all hope lost, and marines closing in, Brown was a tower of strength to the defenders, encouraging, exhorting, and showing by his personal actions an example of courage and resolution. Even the hostages, particularly Colonel Washington, were greatly impressed.

Since the sledgehammers seemed ineffective the marines had to improvise with a heavy 40-foot ladder as a battering ram. Two strong shoves did the trick, and a low hole was punched through the door. As the door gave way, the watching crowds gave a mighty shout of triumph that nearly drowned out the sound of the gunfire that still came from the defenders.

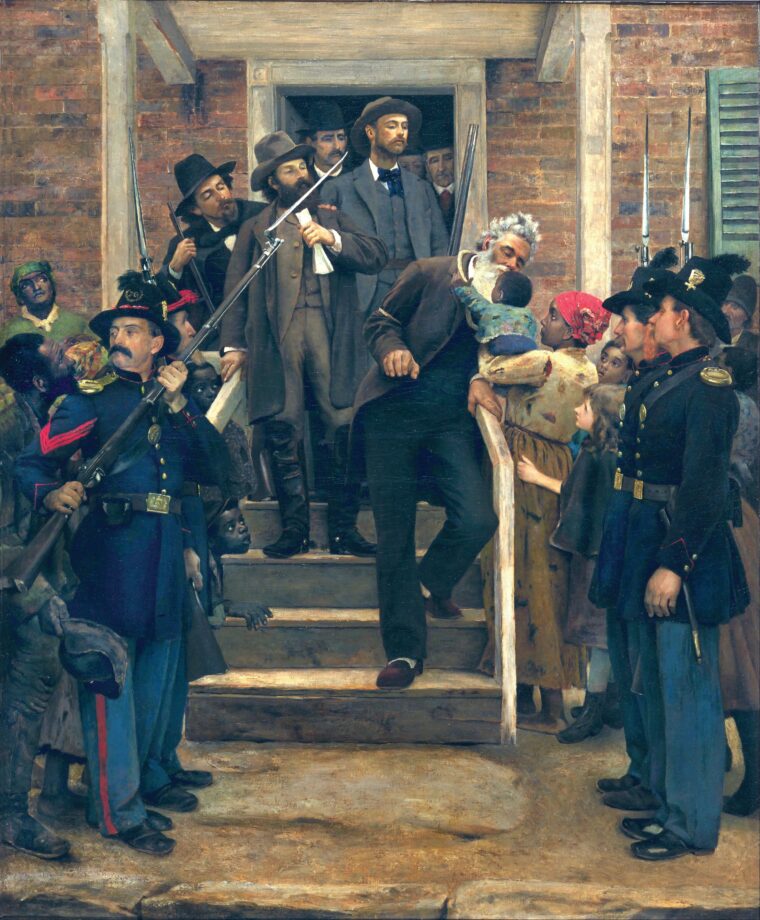

Lieutenant Greene was the first to enter, and as he did so he spied a kneeling man with a carbine, pulling the gun’s lever in an attempt to reload. Green later recalled “Quicker than thought I brought my saber down with all my strength upon his head. He was moving when the blow fell… for he received a deep saber cut in the back of the neck.”

The man Greene has sabered was John Brown. The marine lieutenant instinctively tried a coup de grace by running the saber though Brown’s breast, but the weapon he carried was a ceremonial “dress” saber and bent double instead of fully penetrating. In the excitement and confusion perhaps Greene’s aim was off and he hit Brown’s leather belt.

A Marine private, originally a native of Ireland, was the next man through the door, but as he entered he was hit by a bullet in the stomach. He dropped his musket, staggered a few feet, then fell to the ground. Four or five additional marines entered the building, “rushing in like tigers.” Strict orders had been given not to fire their weapons for fear of hitting hostages, so they went to work with the bayonet.

Raider Dauphin Thompson tried to evade them by hiding under a fire engine, but was soon discovered and bayoneted, while Jeremiah Anderson was impaled against a nearby wall. Both men died of their wounds. The action only took about three minutes. There was only one other marine casualty: Private Mathew Rupert had a flesh wound in the upper lip, and several teeth had been knocked out.

Brown had been severely wounded, and had gone without food or sleep for more than 24 hours. Nevertheless, he was interviewed for an another 24 hours by a number of people, including Virginia Governor Wise. Brown turned the tables on his interrogators, and before long it was almost as if he was holding court rather than languishing in captivity. People like Wise were amazed at his deft answers, and all came away with a grudging admiration for his courage, honesty and truthfulness, if not his cause.

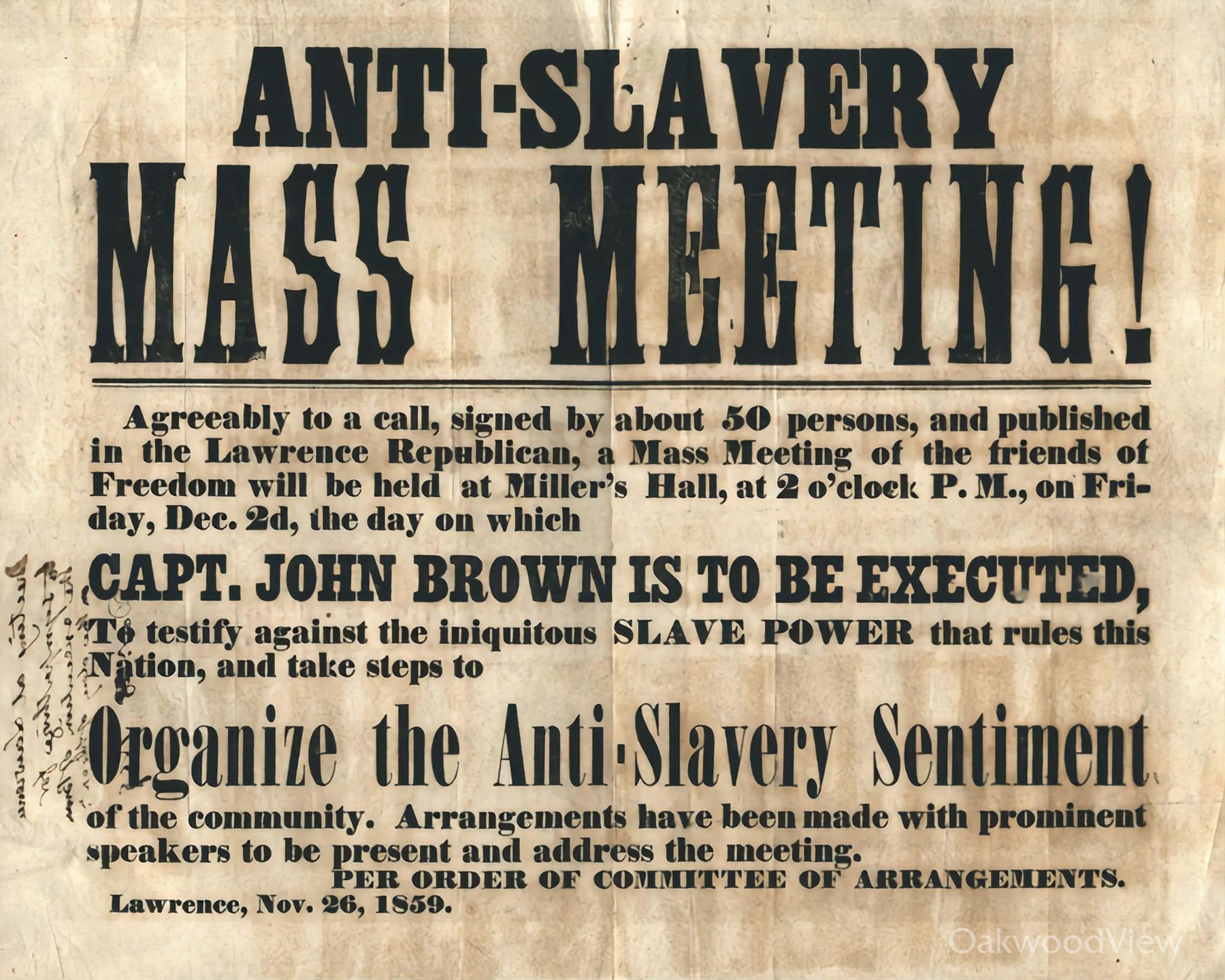

John Brown was tried for murder and treason, and everyone—Brown included—knew what the verdict would be. His followers fared little better. Of the 22 people involved in the raid, Brown included, 10 were killed during the raid, seven were captured and hanged, and five escaped. Brown’s trial received widespread press coverage, and his execution by hanging was witnessed by hundreds, including actor John Wilkes Booth.

Hobbled by an almost crippling lack of men and money, and by political superiors who were biased in favor of the south, the U.S. Army tried to keep the peace and prevent factionalism from tearing the country apart. The army itself reflected the growing divide between north and south, with officers as well as rank and file hailing from different parts of the country. Yet on the whole, with officers like Colonel Edwin Sumner in command, the army managed to postpone the “irrepressible conflict” of the Civil War.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments