By Steven Trent Smith

Sunsets over Manila Bay are nothing less than spectacular. Once the sun dips below the horizon there is a lingering illumination known as “blue hour” as the sky gradually shifts from pale azure to deep indigo before fading completely into the black tropical night. But for the men of USS Seawolf there was no blue hour that warm January evening in 1942. Their submarine rested on the inky bottom of the bay awaiting nightfall, when it would be safe to surface.

At 7:30 pm, Lt. Cmdr. Frederick “Fearless Freddie” Warder, gave the command. The submarine broke the calm waters off the besieged island of Corregidor, sailing cautiously toward South Dock. When Seawolf was securely moored, the crew began transferring her cargo: 36 tons of antiaircraft shells destined for the island’s desperate garrison.

Though Pearl Harbor was barely a month past, this was already Seawolf’s third war patrol. And it was to become a landmark, for it was the first of nearly 300 “special missions” undertaken by American submarines during World War II.

After unloading her cargo, Seawolf embarked 25 passengers for transport to Surabaya on Java’s eastern coast. It must have galled Freddie Warder that his warship had been used as a truck and was about to become a bus. But most of his refugees were VIPs—Very Important Pilots—men who had lost their planes in the first days of the war. It was Seawolf’s mission to deliver those flyers to new aircraft to rejoin the fight.

In those first, dispiriting months of the war, Asiatic Fleet submarines were kept busy on similar missions—so many that the chief, Admiral Thomas Hart, complained bitterly in a report to Washington: “This Command has been continuously attempting to satisfy numerous demands for use of submarines for various evacuation and ferrying trips.” Those trips included transporting high-ranking officials, more pilots, members of a top-secret radio intelligence unit, and 20 tons of gold and silver from the Philippine treasury. They also carried in as much ammunition and foodstuffs as the boats could fit. Hart noted that these special missions detracted from offensive operations, but Washington seemed to pay no heed.

The last trip to Corregidor was made on May 3 by USS Spearfish, redirected from a war patrol off the Lingayen Gulf to pick up 27 passengers. Twelve were Army nurses; two were unauthorized stowaways. The island fortress fell to the Japanese just three days later.

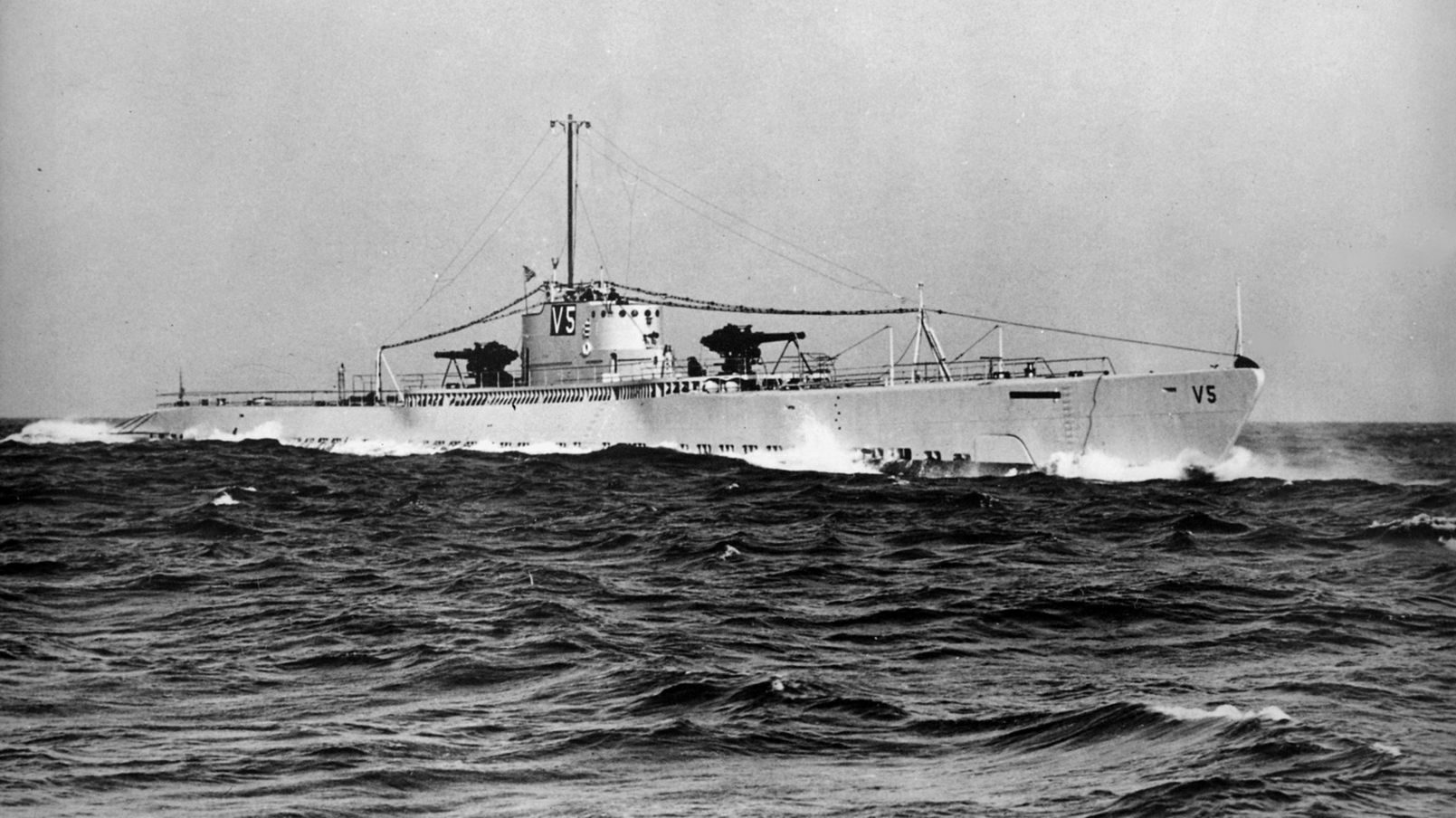

Two Cruiser Submarines and a Minelayer

The typical modern diesel-electric “fleet submarine” of the time was 311 feet long and displaced 1,525 tons. The Navy had three boats greatly exceeding that size: the minelayer Argonaut and the cruiser subs Narwhal and Nautilus. Each was more than 370 feet in length, displaced over 4,000 tons, and was armed with pairs of six-inch guns. Built between 1927 and 1930, the boats were big, slow, and ill-suited for the underwater attack role. It was said that Argonaut’s diving time was four or five minutes.

However unsuitable the trio may have been for deployment offensively, their sheer size proved attractive to Navy planners for special missions.

One of the first was deployment of Nautilus and Argonaut for landing a Marine Corps raiding party on Makin Atoll in the summer of 1942. The assault was meant to divert enemy attention from Guadalcanal, where a full-scale invasion had begun a week before. In all, 252 Marines were crammed into the boats’ torpedo rooms, where the “fish” had been replaced by tiers of bunks.

In the predawn darkness of August 16, the men of Colonel Evans Carlson’s 2nd Raider Battalion launched their rubber boats and paddled ashore to destroy Japanese facilities. While the Marines were on the island, Nautilus had an opportunity to unlimber her six-inch guns. Firing blind, over the island and into the lagoon, the ship managed to sink an enemy patrol vessel and a 3,500-ton freighter.

Nautilus and twin Narwhal were used in a similar capacity 10 months later, when they supported the American assault in the Aleutians, landing 214 Army Scouts on Attu Island. As they had at Makin, the big subs amply demonstrated their versatility as transports.

Aiding Guerillas in the Philippines

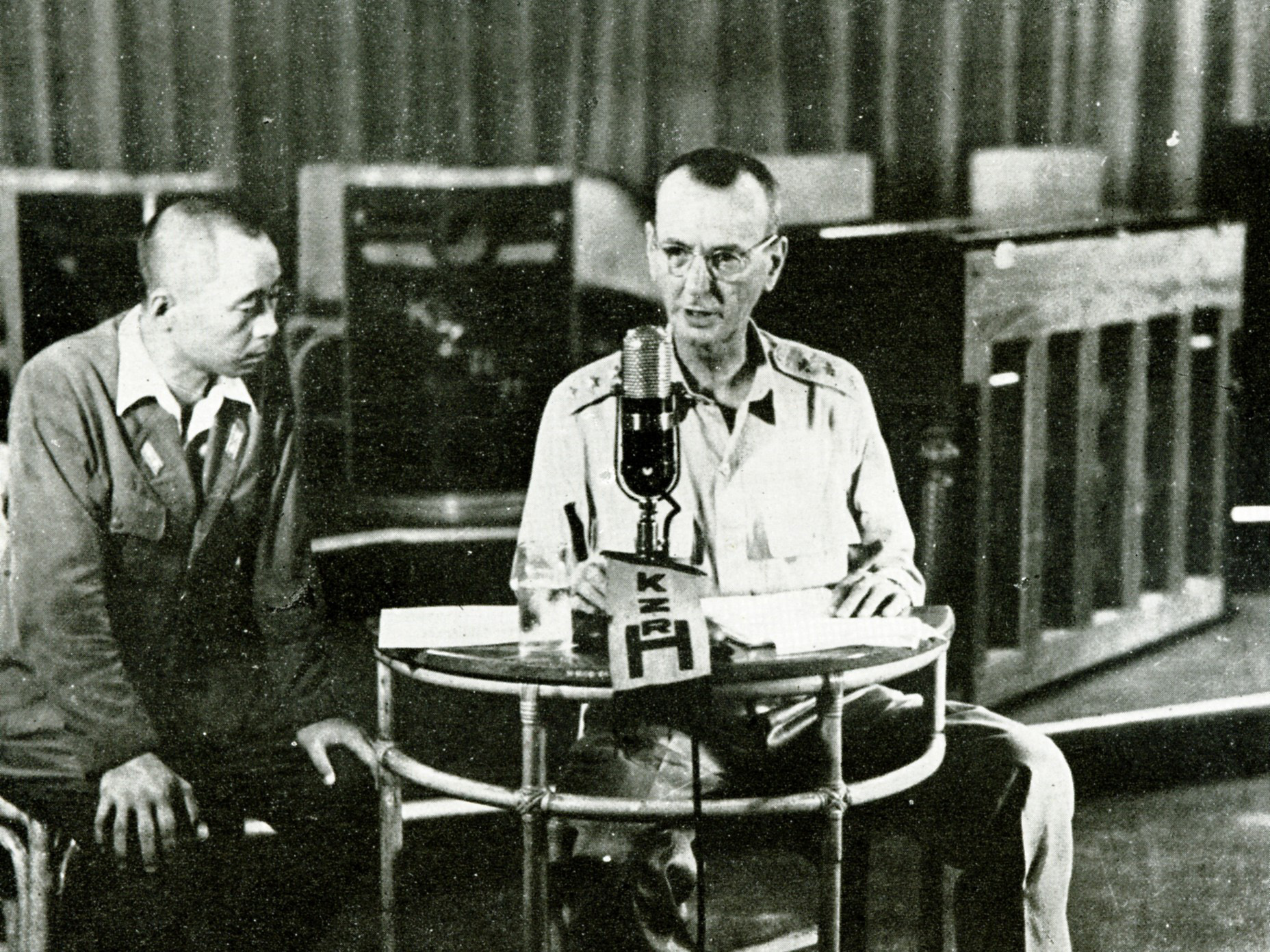

At the beginning of 1943, a whole new phase of special operations began. In January, six agents were landed on Negros in the central Philippines by USS Gudgeon. Code-named Planet Party, the group was led by Captain Jesus Villamor, a much decorated Filipino pilot and war hero. The unit’s task was to set up a communications network that could radio intelligence back to General Douglas MacArthur’s Southwest Pacific Area headquarters (SWPA GHQ) in Brisbane, Australia.

Villamor discovered a flourishing guerrilla organization in desperate need of arms, ammunition, and more. That news excited GHQ, which made arrangements in February for USS Tambor to deliver 70,000 rounds and $10,000 in cash to the rebels on the southern island of Mindanao while en route to her patrol area. Even as she was sailing north, commanders in Brisbane were discussing the feasibility of establishing a regular submarine transport service to the Philippines. “It is suggested that every effort be made to provide [the Philippine] sub-section with undersea boats,” wrote Lt. Col. Allison W. Ind, deputy controller of the Allied Intelligence Bureau on February 25, 1943.

Like Gudgeon, Tambor was also carrying a group of agents, led by an unassuming naval reserve officer, Lt. Cmdr. Charles “Chick” Parsons. He was an old Philippine hand, arriving there in 1921. Before the war he had been an executive at Luzon Stevedoring Company in Manila and seemed to have knowledge of every channel and bay and inlet throughout the islands. He was widely connected and widely respected. After disembarking from the sub, he began an island-by-island investigation of the situation, talking to rebel leaders, observing daily life, forming opinions on the state of the country. He would become, in a very real way, MacArthur’s eyes and ears in the Philippines.

SWPA continued to send men and supplies north—but in ad hoc dribs and drabs. In April, Gudgeon went back with four men and three tons of supplies for Panay Island. And that July, Trout put ashore another reconnaissance party on Mindanao, evacuated four escaped POWs and, after four months in country, Chick Parsons.

On August 20, 1943, Parsons submitted a lengthy report to MacArthur on the state of the Philippines. There were sections on political and economic conditions, on military and civilian internees, and on the morale of the nation under Japanese occupation. Parsons then offered up some thoughts on how the United States might aid the resistance movement. Among them he recommended submarines be employed to supply the guerrilla districts. This idea had been kicking around GHQ for months, but it took another old Philippine hand, Colonel Courtney Whitney, a close friend of MacArthur’s, and before the war a very sharp Manila lawyer, to get the ball rolling.

Spyron’s Inaugural Trip

Until then the Navy had been reluctant to commit a boat full time to the Philippine guerrilla campaign. Whitney, frustrated by the lack of cooperation, persuaded the general to threaten to take the issue to President Franklin D. Roosevelt. It still took six more weeks to convince the Commander Seventh Fleet, Vice Admiral Arthur S. Carpender, that the Navy’s assistance in inserting intelligence teams would produce “information of direct benefit to [the Navy’s] operations against the enemy,” through the establishment of a network of coastwatchers reporting Japanese ship movements, valuable information that would be of paramount interest to patrolling submarines. Carpender went to his boss, Admiral Ernest J. King, commander in chief, United States Fleet, with a recommendation that a Nautilus-class submarine be made available to SWPA to make two trips into the islands toward the end of the year. The plan was approved.

Because of his experience and expertise, Commander Parsons was handed the job of organizing the sub supply system under the aegis of both Whitney and the Seventh Fleet’s director of Naval Intelligence, Captain Arthur H. McCollum. In time the unit came to be called the Spy Squadron, or “Spyron.” From an office in Brisbane, Chick coordinated the materiel requisitions from rebel commanders. Once the freight was assembled, it was forwarded to Darwin on Australia’s north coast for loading aboard the submarines.

Narwhal was made available to Spyron late that autumn after receiving a complete refit, including removal of her torpedo-handling gear to clear space in the torpedo rooms for cargo, though 10 fish were left in her tubes just in case.

And so it was, on October 23, 1943, USS Narwhal, Lt. Cmdr. Frank D. Latta commanding, departed Australia bound for Mindoro and Mindanao. For this inaugural Spyron trip she was transporting two Army radio intelligence teams, 92 tons of cargo, and Chick Parsons. The supplies ran the gamut from rifles, pistols, machine guns, ammunition, grenades, radio sets, medicines, cigarettes, lubricating oil, uniforms, and typewriter ribbons and carbon paper (the rebels had a well-organized bureaucracy of their own), to communion wafers, propaganda, and chocolate bars wrapped in labels emblazoned with “I Shall Return, MacArthur.”

“Mathew, Mark, Luke, and John”

The voyage was routine, at least until November 10, when, at 10:35 pm, lookouts spotted a Japanese tanker escorted by three warships, range 12,000 yards. Latta decided to attack, waiting until the range dropped to 3,100 yards before firing four torpedoes at the target. All missed.

Less than three hours later two of those escorts spotted the old girl and took off in pursuit, one of them opening fire. Latta screamed for more power. The engine men gave him enough to push the boat through the Bohol Sea at an astonishing 19 knots (she was built to top out at 17). In time, Narwhal pulled ahead. When the ordeal was over, Latta christened the diesels that had saved his boat, “Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John.”

Two days later the sub reached Paluan Bay on the northwest coast of Mindoro, where half the cargo was unloaded along with one of the Army teams.

Narwhal then sailed down to Nasipit in northern Mindanao. While maneuvering into the tiny port, the sub ran aground on a shoal. Though it took less than an hour to back her free, those were tense moments for the crew in waters alive with Japanese patrols. When the boat finally reached the dock an enthusiastic Filipino band, resplendent in neatly pressed uniforms, struck up a warm welcome with a rousing rendition of “Anchors Aweigh.”

It took just a few hours to get the remaining supplies ashore. That accomplished, 32 evacuees boarded the boat for the trip back to Australia. Chick Parsons stayed behind with the guerrillas.

Narwhal arrived at Darwin on November 22, 1943, did a three-day turnaround, and headed back to the Philippines with another 90 tons of materiel and 11 men. The trip up was uneventful. The supplies were quickly unloaded, seven evacuees and Commander Parsons embarked, and the boat was steaming back toward Australia by December 2. The voyage was not without some excitement. Latta attacked and sank a Japanese freighter.

Recovering the Z Operations Order

Spyron was off to a promising start. Thereafter, resupply missions were run every four or five weeks. The addition of Nautilus in July 1944 doubled the unit’s carrying capacity. It seems President Roosevelt had urged her reassignment after being nudged by Philippine President Manuel L. Quezon, who sought ever greater support for his country’s guerrillas. In August, two smaller boats, Freddie Warder’s old Seawolf and Stingray, were added to the Spyron fleet.

Even while Spyron operated, other boats continued to run special missions into the Philippines, usually diverted from a regular war patrol to effect an emergency evacuation. In March 1944, USS Angler was sent to Panay to pick up 58 civilians who had been stranded there since the beginning of the war. There was some urgency to her assignment. The Japanese had brutally murdered 17 missionaries and their children just before Christmas, and MacArthur wanted to remove the remaining Americans on the island as quickly as possible.

In May, USS Crevalle was diverted to nearby Negros to bring out 40 people, a mixture of missionaries, civilian contractors, and more escaped POWs. But that was not why she was sent there. A month before, the guerrillas had come into possession of a briefcase full of top-secret Japanese Navy papers following the crash of a flying boat carrying a high-ranking officer. When rebels radioed MacArthur that they had these mysterious documents, GHQ hastened to send a submarine to pick them up. Crevalle just happened to be the closest.

Embarking the 40 provided a neat cover story for the real mission In fact, they would have been evacuated by Narwhal or Nautilus within a few weeks. When the papers got back to MacArthur, they were quickly translated and analyzed. The cache turned out to be the Z Operations Order, a strategic battle plan for the defense of the Western Pacific. American forces used the intelligence to their advantage that June in the invasion of Saipan and the Battle of the Philippine Sea.

From Spyron to the Lifeguard League

In early 1945, when most of the Philippines was back under American control, Spyron was dissolved, and any special missions required were once again assigned to operational subs.

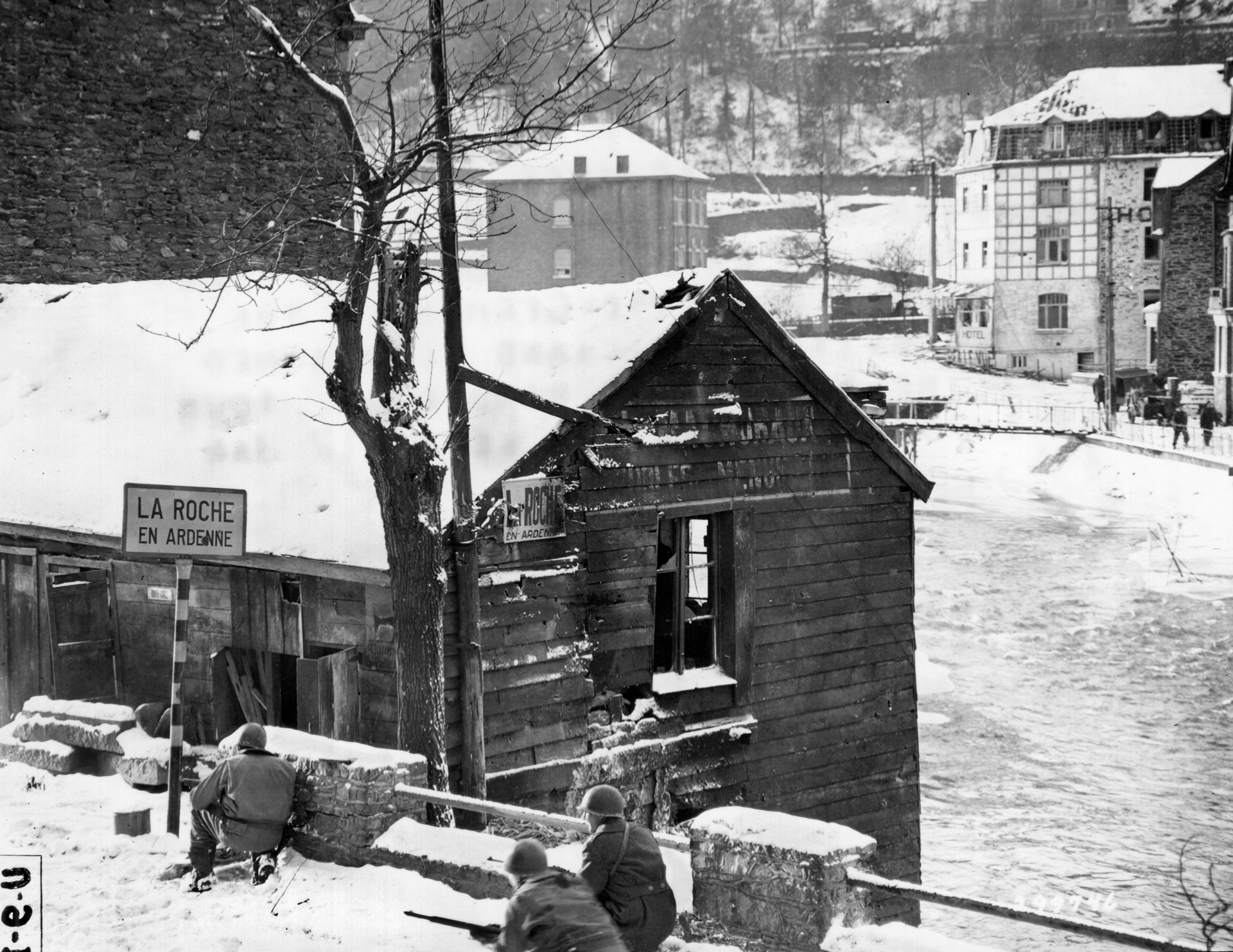

When the great offensive across the Central Pacific opened in late 1943, another phase of special missions began. During air strikes against enemy-held islands and atolls, subs were stationed offshore to rescue any pilots that went down. Over the next 18 months, more than half the boats in the submarine force participated in what came to be known as the Lifeguard League. Perhaps the best known incident was USS Finback’s September 1944 rescue of a young Grumman Avenger torpedo bomber pilot, Lieutenant (j.g.) George H.W. Bush. Perhaps the hairiest was USS Harder’s April 1944 extraction of a pilot at remote Woleai Atoll in the eastern Carolines.

The sub, commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Samuel D. Dealey, was assigned lifeguard duty there to cover a bombing raid by carrier-based planes. On April 1, Dealey received a radio message telling him that a fighter pilot was down on the beach. Harder sped to the scene, easy to find because other aircraft were circling overhead.

The skipper conned his boat as close to the reef as he dared. “White water was breaking over the shoals only 20 yds in front of the ship and the fathometer had ceased to record,” he wrote in his patrol report. Harder was literally between a rock and a hard place, so the flyers suggested backing off and trying a different approach. No sooner had the sub begun to maneuver away than the stranded pilot, Ensign John R. Galvin, fell to the ground in profound despair, thinking his saviors were abandoning him. “My heart stood still,” he said.

The new spot did not pan out, so Dealey returned to the first and began in earnest to execute a rescue. He put over a rubber boat that had no paddles and three volunteers. Word came up from the forward torpedo room that the sub’s bottom was scraping the coral. Dealey, worried that Harder might get pushed broadside by the surf, “worked both screws to keep the bow against the reef.” If that was not enough, enemy snipers hiding in the palms along the beach kept up a continuous fire. “Bullets whined over the bridge, uncomfortably close,” the skipper noted.

The volunteers had a 1,200-yard swim to the beach. It took them half an hour to reach Galvin, who had by then climbed into his own raft and was being pushed by the currents away from his rescuers. Finally, they got the pilot into their boat. Sailors on the sub began to haul in the line to the raft, but an over-exuberant, would-be rescuer in a Curtiss floatplane managed to sever it while taxiing toward Galvin. Another Harder crewman had to swim out with a second line, and slowly the raft was pulled alongside the sub.

Despite the mishaps, the entire rescue took just an hour and 19 minutes. But to all involved, it must have seemed an eternity.

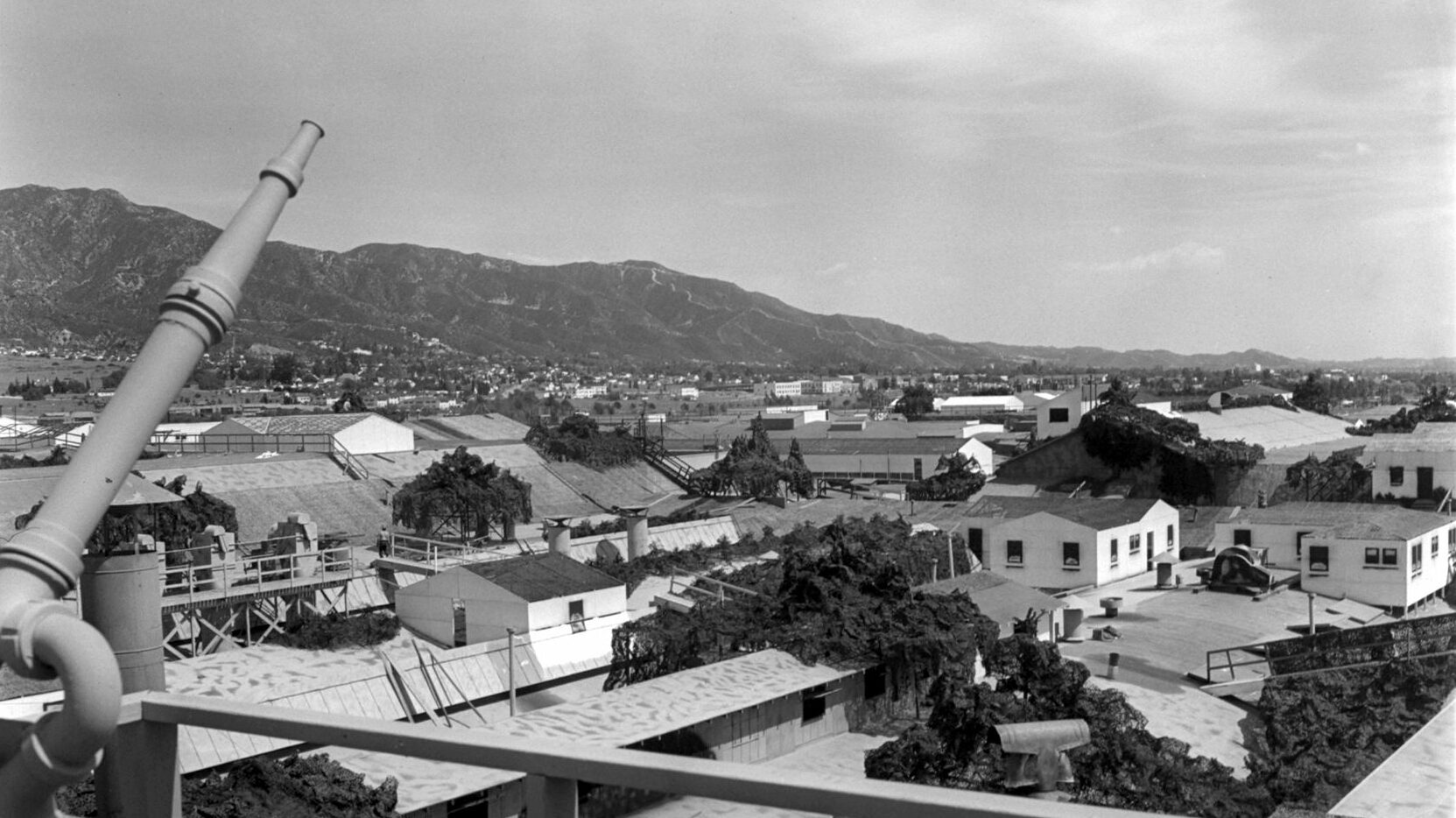

The Hellcats

Throughout the final months of the war, fleet submarines continued to conduct special operations. Many involved landing intelligence teams throughout Southeast Asia. But in April 1945, Tigrone and Rock teamed for an unusual mission to use their five-inch guns to knock out an enemy radio station on Batan Island in the Luzon Strait.

Also that spring a group of boats conducted a series of special missions as guinea pigs for a new kind of Frequency Modulated (FM) sonar designed to detect underwater mines. It was not a particularly popular assignment. In June 1945, a group of nine FM-equipped submarines dubbed the Hellcats successfully penetrated the minefields guarding the southern entrance to the Sea of Japan. In 15 days they managed to sink 28 enemy ships at the cost of one of their own, USS Bonefish.

The final official submarine special mission was run by USS Catfish. On August 15, 1945, the boat began an FM sonar sweep for mines off the coast of Kyushu. None were detected, but after surfacing at the end of the day, the ship’s radioman picked up a flash. “Received War News and heard war was over,” the skipper wrote in his report. “News was received in ‘proper’ manner by all hands. Now the topic is ‘When can I go home?’”

Stunning Successes of Spyron and the Lifeguard League

When the record of the submarine force was compiled after the war, the results were impressive. The boats had accounted for 55 percent of all Japanese maritime losses. And the record for special missions was equally impressive. In fact, 15 percent of all patrols were either wholly special operations or had a special operations component.

Chick Parsons’s Spyron unit delivered 1,325 tons of supplies and 331 personnel and evacuated 472, most of them civilians, many of these women and children. Parsons himself made eight round trips to the Philippines. A 1948 SWPA assessment of Spyron said, “The practical importance of this efficient supply service by cargo submarine can scarcely be overestimated. It became the ‘life-line’ of the guerrilla resistance movement.” Narwhal was withdrawn from service in January 1945, having made nine cargo runs. Nautilus was sent home in April with six under her belt. Spyron had one tragic loss. Seawolf went down with all hands during an October 1944 mission, very likely sunk by an American warship.

The Lifeguard League delivered 504 flyers from certain death or capture by the enemy. The record rescuer was Tigrone, which plucked 31 airmen from the Pacific. The valiant Harder, heroine to Ensign John Galvin, did not survive the war. She was lost with all hands on August 24, 1944, after a brutal depth charging in the South China Sea.

On hundreds of special missions throughout World War II, American submarines performed myriad tasks, always at enormous risk to the crews and their boats. In the process they played a manifest role in winning the war in the Pacific.

Anybody know anything about a sub landing American paratroopers on Mindoro and the nature of their mission?

Nice article.

You mention at the end the “enormous risk.” The two US Navy specialties that suffered the highest casualty rates were aviators and submariners – approximately 30%.

The article mentions the number of pilots rescued by submarines. I understand that the standard “ransom” for a rescued flyer was 10 gallons of ice cream. The carriers could make ice cream but, of course, submarines were too small. A small treat for some very brave men.