By Flint Whitlock

From their hiding places in the valley below, the soldiers looked up at the wall of shale looming more than 3,000 feet above them. The ridge was nearly denuded; most of the vegetation on its steep slopes had already been chopped down for firewood by the starving Italian people in the villages scattered along the banks of the Dardagna River—a rocky, swiftly moving stream at the base of the cliff.

The soldiers studied the rock face for a very long time, speaking quietly as they scanned the shale with binoculars and jotting notes onto a map of the area. The map named this series of connected peaks Monte Della Riva. The troops simply called it Riva Ridge. They could see places on the ridge that looked fairly easy to navigate, and other parts of the trail that offered more of a challenge—places where snow and ice clung to shadowy crevasses, places where small waterfalls cascaded over rock, places where the shale looked loose and easily broken. What they could not see but knew was there was an alert German battalion on the summit, just waiting for the Allies to make another foolhardy attempt on the neighboring mountain, Monte Belvedere.

Ordinary soldiers might have been daunted by the geological feature rising in front of them. But these were not ordinary soldiers. These were members of an elite outfit called the 10th Mountain Division—the only American division specially trained for mountain and winter warfare. And they had been hoping, praying, and hungering for four years for just this opportunity. The young men reconnoitering Riva Ridge this cloudy February morning were smiling. Their eyes gleamed with the excitement of young boys who had found some secret treasure. They were figuratively licking their chops because, at last, they finally would be able to prove themselves in combat. They had a thirst for battle because they had not yet tasted its bitterness.

The 10th Mountain Division thus far had been spared the brutal mountain fighting that had begun to take its toll on Allied forces in Italy almost immediately after the landings in the Gulf of Salerno on September 9, 1943. The 10th had not had to endure the agony of the winter fighting around Venafro; had not been forced to attempt the ascent to Monte Cassino; had not been torn to shreds trying to cross the Rapido River. The names of Italian towns and mountains where terrible battles had been fought—San Pietro Infine, Castel del Rio, Mignano Gap, Futa Pass, Livergnano Escarpment, Monte Lungo, Monte la Difensa, Monte Maggiore, Monte Summucro—were simply words the soldiers had read in Yank or The Stars and Stripes, and held no special meaning, no special nightmares.

General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied Commander, had called the division a bunch of “playboys”—and with some justification. No other infantry division had a higher collective I.Q. or a higher percentage of high school and college graduates in its ranks. Many of the mountain soldiers had been hotshot skiers from East Coast prep schools and Ivy League colleges. Many of the sergeants, such as Walter Prager, had been college ski coaches, instructors at resorts such as Sun Valley, or members of their college ski teams. Quite a number were foreign-born, world-class skiers and mountaineers from Norway, Switzerland, even Austria. One was a member of the von Trapp family, immortalized by the 1965 film, The Sound of Music. They were cocky, arrogant, and brimming with self-confidence. Their commanding general, George P. Hays, had even won the Medal of Honor in World War I and inspired them with stories about the glory of combat. They had trained for two years high in the Colorado Rockies at Camp Hale, where they had been toughened by blizzards, then baked in the broiling heat of a Texas summer at Camp Swift prior to their deployment to Italy. They were as fit and ready and motivated as any unit anywhere.

The 10th was one of the first units formed at the beginning of the war, and one of the last to be deployed to combat. Because it was so highly specialized, with 75mm howitzers instead of 105mm and 155mm guns, tracked Weasels instead of trucks, and 5,000 pack mules and horses at a time when the Army had all but phased out animals, the 10th found no takers when Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall offered it to various theater commanders.

One of its regiments, however, the 87th Mountain Infantry, had been deployed in August 1943 to the Aleutians, where it had splashed ashore at Kiska as part of a 40,000-man invasion force, only to find the occupying Japanese enemy had gone. The deaths and injuries caused by “friendly fire” on the fog-shrouded peaks before it was discovered that the enemy had been evacuated before anyone knew it, while regrettable, simply did not count as being in combat to the men of the 10th.

But now, in February 1945, they would finally get their chance. Riva Ridge was just one set of peaks in the northern Apennines, some 160 miles north of Rome and 35 miles north of Florence, which guarded the approach to the vital Po River Valley. For 17 long, agonizing months, the Allies had been slowly pushing the Germans north from Salerno in a bloody war of attrition. Since the autumn of 1944, the Allies had been trying to break into the Po Valley but had nothing to show for the effort except mounting casualty lists.

That fall, with the Italian Campaign having taken a backseat to the main thrust across the continent of Europe, reinforcements and replacements were hard to come by. Indeed, General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army seemed to be cobbled together. Besides American units (including the only all-black infantry division, the 92nd), the Fifth had troops from Brazil and South Africa. Fresh blood was needed to break the stalemate in the mountains, and Clark thought that the 10th, despite all its animals, was perfect for the job.

At Thanksgiving 1944, the division, which many at the War Department had wanted disbanded and its troops parceled out as replacements, was finally alerted for overseas movement. By the end of 1944, the division was in Italy and was north to the front, where it was ordered to hold the line between the 92nd Division on its left and the Brazilian Expeditionary Force on its right. Ahead of them were the German 4th (Edelweiss) Mountain Battalion and elements of the 232nd Infantry Division of the 51st Mountain Corps holding snow-covered Riva Ridge, Monte Belvedere, Monte Della Torraccia, and more.

At first, the 10th acclimated itself to the terrain and weather. Patrols on skis and snowshoes probed toward enemy lines. One night, American Olympic ski racer Steve Knowlton was on a ski-mounted patrol when the Americans encountered a German, also on skis. Thinking the Americans were his kameraden, the German nonchalantly waved, only to be greeted by a volley of fire. Turning quickly, the German schussed down the hill only to crash into a grove of trees and break both legs. “The bullets didn’t stop him, but the trees did,” Knowlton remarked.

Bud Lovett, a medic, recalled an incident on another patrol. “I saw a German on skis standing on a snow dam between two ridges. We ordered him to put his hands on his head. He stood and looked at us, then did a jump turn and skied right down that thing as if it were a headwall. Nobody shot at him; I think most of us were impressed by his skiing.”

During those first few weeks following the 10th’s entry into the line, there was little heavy fighting, only sporadic and desultory exchanges of artillery. But General Hays had not brought his men all this way just to hold a defensive position, and soon a new offensive was in the works, one that would pit the 10th Mountain Division in the valley against the Germans holding the high ground. Hays’ staff officers pointed out that previous attempts to take Monte Belvedere, overlooking Highway 64, had failed because German artillery observers on Riva Ridge could spot any movement toward the mountain and bring deadly accurate fire down upon the attackers. The key to taking Belvedere, they argued, was Riva Ridge. The operation, then, was planned for Riva Ridge to be assaulted and held the night before the main assault climbed Monte Belvedere. But, first, routes to the top of Riva Ridge needed to be found.

It took over a week for the scouts of the 10th to plot the routes, but eventually five trails were mapped out. The thousand-man 1st Battalion of the 86th Mountain Infantry Regiment, augmented by F Company from the 2nd Battalion, was detailed for the mission. D-day for the operation was February 19, 1945. Half a world away, on that very date, U.S. Marines were storming ashore at an island called Iwo Jima.

On the night of February 18, all was in readiness. Hiding in the villages at the base of Riva Ridge were over a thousand anxious Yanks, primed and ready for the operation. At the appointed hour, they moved out, crossed the narrow, swiftly running Dardagno, and began the upward climb. Unlike most assaults, this one was conducted with no preliminary artillery bombardment; there must be nothing to tip off the enemy that an attack was about to be launched. The advance climbing party even wore soft caps so that no helmet would rattle or fall off and clatter down the rocks. Absolute noise discipline was observed; the slightest sound could alert a sentry and bring the firepower of the garrison atop Riva Ridge down upon the attackers.

Aiding the climbers’ ability to see was “artificial moonlight.” From across the valley, searchlight beams were bounced off the heavy cloud cover, and the reflection provided just enough illumination to allow the men of the 10th to find their way to the top. Fortunately, a patchy fog kept any curious Germans from peeking over the top of the ridge to see the attackers coming. Also fortunately, the Germans had posted no sentries below the summit; they were convinced that no one could possibly attack them from the cliff side.

The climb took all night. At dawn, the raiders slipped over the crest of the cliff and caught the Germans napping in their foxholes. “They hadn’t even had their first cup of coffee yet,” commented one mountain trooper. Some of the stunned Germans tried to fight back but were quickly silenced. The off-duty troops, resting in the bunkers on the gentler reverse slope of the ridge, began piling out in various stages of undress, only to be hit by volleys of American fire.

Bart Wolffis of the 86th Regiment’s Company A and two others rushed over the top of the ridge only to hit a patch of ice. “All three of us landed on our butts and started sliding down the German side of the hill. All I could think of was, ‘We’re going to slide right into the Germans.’ We were using our rifle butts to try and stop us from sliding. As it turned out, there was a fairly shallow bowl and we slid to a stop.”

Moments later, Wolffis recalled spotting eight Germans a couple hundred yards away. “They didn’t know we were there until we began to fire at them, and then they ran into a bunker. A couple of them then came out and took up firing positions. Every now and then, a reserve company of Germans would [appear], quite a ways behind where the other ones were that we were firing at. They were across a big snow field, and every time they’d get about halfway across, we’d call for artillery fire and that would break up the counterattack.”

All across the five-mile-long ridge, war on a small scale was waged, with the five companies of Americans, who now held the higher ground, raking the counterattacking Germans with all manner of rifle and automatic fire, grenades, mortars, and artillery. So complete was the surprise that very few of the 10th Mountain men were hit, but the battle was costly for the defenders.

Nowhere was the fighting more intense than on the far eastern spur of the ridge known as Pizzo di Campiano. Here, Lieutenant James Loose and a dozen of his men from Company A of the 86th became separated from the rest of their platoon and encountered two enemy companies—a much larger force than intelligence had estimated was there. At 0500 hours, the battle for the spur began. The Yanks were hit by a flurry of grenades, then attacked several times, each time fighting off the attacks with their dwindling supply of ammunition.

Even though the rest of Riva Ridge had been secured by the 10th in just a few hours, the battle for Pizzo di Campiano lasted all day and through the night; reinforcements could not reach the men. The next day, when at last it appeared that the cut-off, half-starved Americans were about to be overrun, Loose called artillery down on his own position and broke up the attack. The battle continued to rage through the next day until a relief column, led by the battalion commander, finally reached the summit.

After midnight, Loose and his tattered unit finally came off the mountain. Loose, who had only a handful of men wounded, said, “Last thing I told the platoon leader who relieved us was, ‘They’ve attacked us from every direction but one, and that’s the way we came up. And that’s the way they’re going to attack next.’ Those Germans hadn’t given up; they were still at it. They never stopped. Morning, noon, and night, they were still after us. It got awful tiresome. And, lo and behold, next morning, I stood down below and I could see the Germans, climbing up the same slope we had climbed, to attack that platoon from the rear.”

As scheduled, the night of February 19 saw the 10th’s other two regiments—the 85th and 87th, along with the rest of the 86th—move out of their hidden assembly areas and begin the long, slow, and tense climb up Riva Ridge’s neighbors, Monte Belvedere, Monte Gorgolesco, and Monte Della Torraccia. With 95 percent of Riva Ridge now under new management, the Germans who had used the ridge as an observation post were unable to sound the alarm and direct artillery fire upon the attackers.

Once again, the assault was not preceded with an artillery barrage. But the Germans, who by now knew that Riva Ridge had fallen, were on full alert. As the mountaineers snipped their way through barbed wire, they triggered mines, which then brought down a torrent of German fire. Parachute flares popped overhead, turning the night into a ghostly day, while tracers tore bright paths through the night sky. Yet, the small clumps of men moving uphill did not waver. These highly disciplined troops did not run away, as ordinary people would. Perhaps it was the months and years of training for just this moment. Perhaps it was the fear of shame at fleeing in the face of undeniable terror and leaving one’s buddies to face the horror alone. Or perhaps it was an ineffable sense of duty. Whatever it was, it kept them going up the hill in the face of an incredible amount of metal being thrown at them by the enemy.

The battle for the Belvedere hill mass went on through the night and into the next day. The fighting was terrific. Marty Daneman, a soldier with Headquarters, 2nd Battalion, 85th Regiment, recalled being caught in a grove of trees during an enemy barrage: “The crescendo of the shellbursts continued. For what seemed like hours, shrapnel, shrieking through the air a few inches over my head, tore gaping holes in the tree trunks, sending them crashing to the ground.”

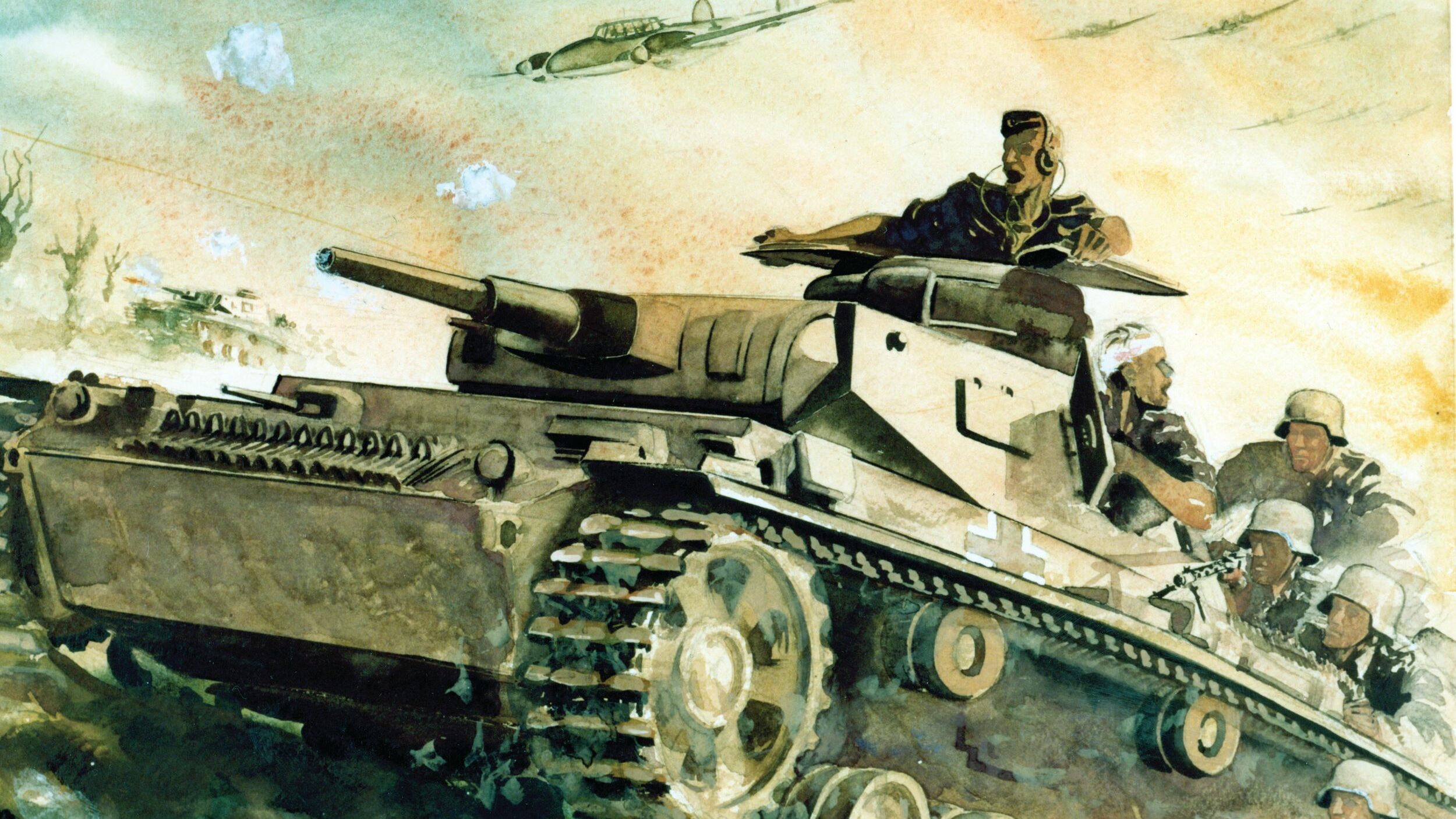

Supported by Sherman tanks of the 751st Tank Battalion, the mountaineers gradually pushed the Germans out of their bunkers and off the heights, only to be on the receiving end of tremendous artillery and mortar barrages and numerous disorganized counterattacks that took place for four days. Despite the bitter fighting and the heavy casualties, the hill mass was finally secured by February 24. The 10th had had its long-sought baptism of fire. Most importantly, the mountaineers had proven themselves and had accomplished their mission; the German grip on the northern Apennines was finally shattered.

In the weeks and months to come, the 10th spearheaded the Fifth Army drive out of the mountains and into the Po Valley. The Germans were now fleeing for the safety of the Alps and doing everything within their power to stall the 10th’s pursuit. But the 10th would not be denied. The mountaineers paddled across the Po while under enemy fire; they were the first American division to cross this river. Up along the shores of Lake Garda, Italy’s largest lake, rolled the 10th, and then across the lake in amphibious DUKWs, where they occupied former Italian dictator Benito Mussolini’s abandoned villa.

Then it was into a series of highway tunnels into which the Germans fired their deadly 88s and tore the Americans apart. Eventually, the 10th reached the towns of Nago and Torbole where, on April 30, 1945, Assistant Division Commander William O. Darby, the founder of the Rangers, was killed by one of the last shells fired during the war in Italy. Two days later, the Germans in Italy surrendered. The war in Europe was almost over.

Through no fault of their own, the 10th Mountain Division was a Johnny-come-lately to combat. Yet, the division had performed brilliantly, never losing a battle or giving up an inch of ground. But the cost of victory was high. In only 114 days of combat, the 10th lost nearly 1,000 men killed and over 4,000 wounded.

The division’s contribution to victory did not pass unnoticed. Mark Clark wrote, “The 10th Mountain Division, which entered the line only last January, has performed with outstanding skill and strength.” General Hays, the 10th’s commander, told his men, “I am proud indeed that the knockout thrust has been spearheaded by the 10th Mountain Division….When you go home, no one will believe you when you start telling of the spectacular things you have done. There have been more heroic deeds and experiences crammed into these days than I have ever heard of.”

The men of the 10th celebrated the end of the war in the one way that seemed uniquely appropriate for them: They organized a ski race. On the crusty summer snows of Mount Mangart, where the borders of Italy, Austria, and Yugoslavia come together, the 10th’s best skiers challenged each other. First Sergeant Walter Prager, the Dartmouth ski team coach, won. It seemed a fitting way not only to end a war, but to begin a new world. n

Denver resident Flint Whitlock, son of a 10th Mountain Division veteran, is the coauthor, along with Bob Bishop, of the definitive history of the division, Soldiers On Skis: A Pictorial Memoir of the 10th Mountain Division.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments